Kashmir School of Miniature Paintings

It is for the first time in the history of Indian, or world, art that miniature paintings of the Kashmir school are being displayed in an exhibition. With the solitary exception of a recent work by a Russian art historian, no attempt has been made so far for a systematic study of this important school of art.

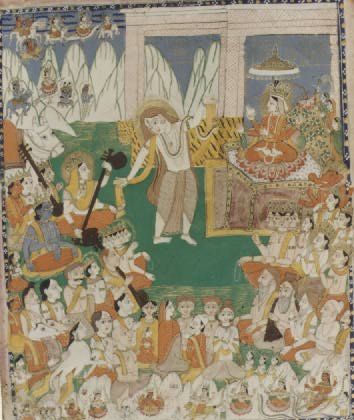

Shiva Dancing

Shiva DancingThe story of art in Kashmir opens with a pre-historic rock drawing discovered at the Neolithic site of Burzahom depicting a hunting scene. A subsequent stage of development is represented by master-pieces of art in the shape of Harwan tiles and Ushkar (Wushkar) stucco figures. The Nilamata Purana makes clear reference to the existence of painting in ancient Kashmir. From 7th-8th century onwards the school of Kashmir art acquired distinct features, even as it was absorbing Gandharan and Gupta influences reaching its pinnacle of glory in the times of Lalitaditya. The movement sustained till the 10th- 11th century when its fame spread throughout the Himalayan region.

Although no direct example of Kashmir painting of this period has survived, the characteristic features of the Kashmiri style can be clearly seen in the Gilgit manuscript paintings assigned to the 6th-7th century. The murals of the Buddhist monasteries of Alchi in Ladakh, Mang Nang in Western Tibet and Spiti in Himachal Pradesh present a successive stage of the development of the tradition of painting in Kashmir. These mural paintings appear to be a pictorial translation of the exquisite Kashmir bronzes dated to 9th to 11th century.

The Kashmiri artistic tradition faced decay during the political and religious upheaval in the 14th century. Lack of patronage and fear of religious persecution forced master painters of Kashmir to neighbouring Himachal princedoms where the Kashmir style revived and flowered after being grafted into the Pahari-Kangra school.

Despite large scale vandalism and destruction in the subsequent centuries, the traditional artistic propensities of the Kashmiris could not be entirely stiffed though. The Kashmir school of miniature painting survived taking a new avtara during the late 18th century, continuing through the l9th century to the early decades of the twentieth. The Puja room (thokur kuth) of the Kashmiri Brahmins became a virtual museum of religious art which found expression in the illuminations of Sharada manuscripts, horoscopes, folk-art works like the krulapacch, nechipatra (almanac) etc. besides individual paintings. The themes were essentially religious with forms of Hindu deities and local gods and goddesses dominating.

In fact miniature paintings became a family tradition, passing from generation to generation. It even became a collective act of creativity with one expert making the border, another executing the drawing and a third one painting the colours. These Kashmir miniature paintings are characterized by the delicacy of line introduced to the massive and weighty proportions of form, the colour scheme being throughout soothing, soft and harmonious. The facial type, in the words of Dr. A. K. Singh, is "marked with ovaloid face, fleshy cheeks, double chin, aquiline nose and full lips, highly arched eyebrows and almond shaped eyes". The division of space has the unique characteristic of correlating the foreground and background. Ornamental border, with occasionally strong use of gold, is another striking feature of the school.

Unfortunately, this rich treasure of miniature paintings has gone virtually unnoticed by art historians, making it difficult to reconstruct a chronological history of the Kashmir school. 'Unmeelan' is an attempt to invite the attention and appreciation of art lovers and conneisseurs to this very important but neglected school of art.

Source: Unmesh Image Gallery: https://koausa.org/site/gallery/categories.php?cat_id=124