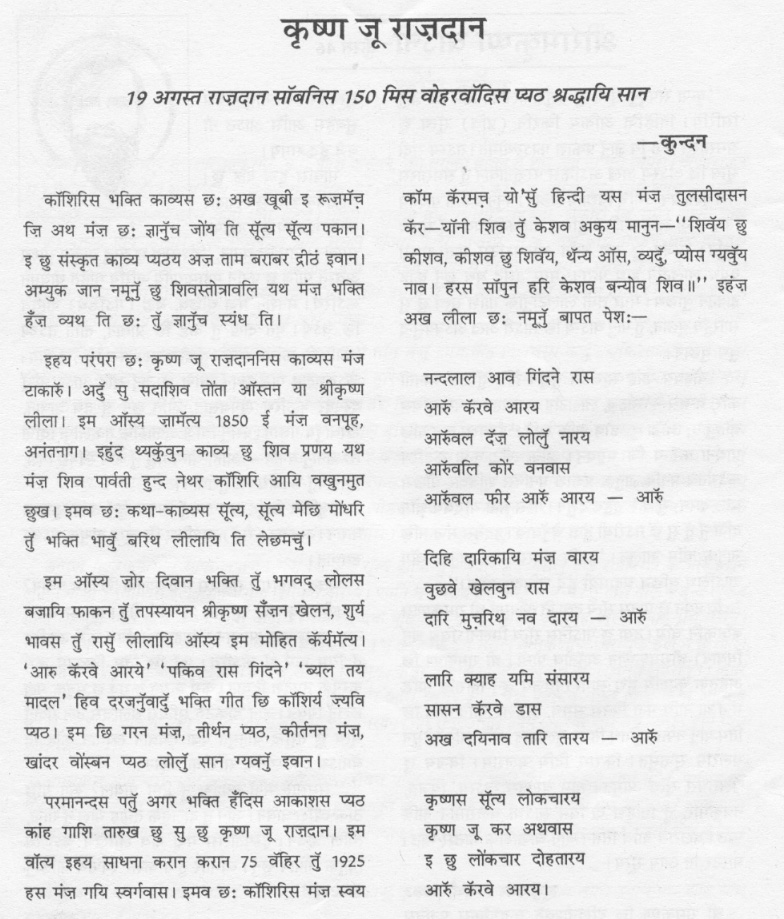

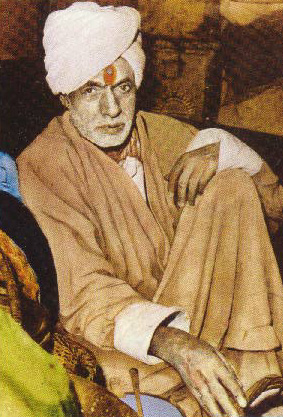

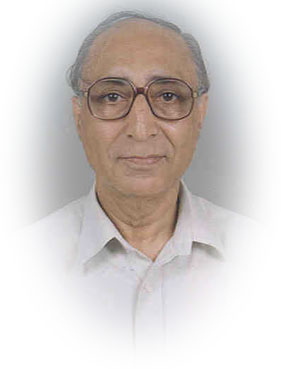

T. N. Dhar Kundan

Sh. T. N. Dhar 'Kundan' has written exclusively on Kashmir, its political scenario and religious practices of its original inhabitants, the Kashmiri Pandits, and has authored several books on a variety of socio-cultural topics. For a number of years, he served as an editor to Koshur Samachar, a tri-lingual publication of Kashmir Samiti, New Delhi. We at KOA are indebted to him for sharing some of his articles with our readers.

List of books written by T.N. Dhar

English

1. A Portrait of Indian Culture published by Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan.

2. A Window on Kashmir

3. Bhagavad Gita, the Elixir of Life

4. Exploring the Mysterious

5. Understanding Education

6. Philosophy of a Common Man

7. Saints and Sages of Kashmir

8. The Saint Extra-Ordinary, Bhagavaan Gopinath

9. Kashmiri Pandit Community- a Profile

10. On the Path of Spirituality

Serial No. 2, 3 and 4 published by Mittal Publishers, Ansari Road, Darya Gunj New Delhi. Serial No. 5 and 6 published by Rajat Publishers, Ansari Road, Darya Gunj, New Delhi. No.7 published by Bhagavaan Gopinath Trust and No 8 by A.P.H. Publishing Corporation, Ansari Road, New Delhi.

Hindi

1. Main Pyasa Hun (I am Thirsty) - A collection of Hindi Poems

2. Main Samudra Hun (I am an Ocean) - A collection of Hindi Poems

3. Guru Se Samvad (Dialogue with a Preceptor)

Kashmiri

1. Swapna ta Sonch (A Dream and a Thought) - A collection of Kashmiri Poems.

Articles

Falsehood and Reality

by T.N. Dhar 'Kundan'

Sometimes when I sit reflecting in the cozy corner of my room, I find myself entangled in a strange situation. First of all I am confronted by the notion ‘I’. This dominates my mind and my thinking. I relate everything to this ‘I’. I evaluate everything with reference to this ‘I’. This is my ego that makes me haughty and arrogant. Then I get the notion that I do this and I do that. I think that what all is happening through me is done by me, at my will and at my command. This gives me a false notion of doer-ship. I feel that I have the authority and the capability to do anything as I will and wish. Thereafter I am ridden with another notion that I enjoy this and that bounty of nature. I feel that I am enjoying various fruits, foods and dishes. I take pleasure in donning various types of dresses and clothes. I feel secure in palatial buildings with a variety of things around for me to use with pleasure. I enjoy music, various other arts, items of recreation and pleasure, the beautiful and bountiful nature and the company of fellowmen as also birds and pets that I like and keep. This gives me the notion of enjoyer-ship. Then I have the feeling that I own a vast number of things, family, friends, wealth, houses, vehicles, various gadgets and innumerable other items of usage. This gives me pride of the possession. Thus I am enveloped by the ego, by the false notions of doer-ship, enjoyer-ship and the sense of possession. I feel I am on the top of the world. I can create and produce. I can protect and preserve and I can destroy what I do not like.

Whenever someone comes to me for some help, I either blankly turn him back saying that he will not get any favour from me, or feel flattered that some needy person has approached me for help. I do the needful, feel proud of the same and want him to remain obliged ever after for this act of kindness on my part. Little do I realize that he had not approached me for help on his volition but had been directed by the Divine to do so, since the Divine wanted me to be the medium for the fulfillment of his desire and give me the credit for this act of kindness. I should know that the Divine executes everything but remains behind the screen, in the background. He creates a cause for every end result that He plans and accomplishes the desired objective as an effect of the same. This cycle of cause and effect continues in the entire cosmos and we become actors in this celestial drama and thereby get credit or discredit for these end results. Had I realized this fact of the nature I would have never claimed to be a doer of any act and consequently I would have escaped credit or discredit for the happenings.

My need is limited but my greed is enormous. Nature has provided me with sufficient means to meet and satisfy my needs but I am not satisfied with that. I strive incessantly to add more and more to all that I have access to. Sometimes I succeed and sometimes I do not. When I fail I feel frustrated and disappointed. When I succeed I want to add still more to it. This syndrome of unfulfilled desires and constant endeavour to satiate my greed keeps me on tender hooks and never allows me to rest on my laurels. The greed, like a mirage, keeps on shifting its posts and I go on living with unrest and turbulence in my mind. Peace, satisfaction and contentment elude me. If only I remembered a verse written by Kabir I would be ever satisfied, contented and consequently happy. He has written, ‘Chah gayi chinta miti manuva beparvah, jisko kuchh nahin chahiye soyi sahansah - Desire is gone, the worry is gone. Those who want nothing are the real emperors in this world.’

Enjoyment is another area where I feel cheated. I taste something which I devour and feel happy. Once it goes down the gullet there is no trace of any taste. I wear something which attracts me and next moment it is torn and I feel sad. I indulge in anything that pleases me but the pleasure is transient and momentary. I still crave for a lasting pleasure. Little do I realize that it is not I who enjoys but some power which is within me and within everything else that actually enjoys. Or at least I should understand that I am trying to derive pleasure from transient things and acts with the result that the pleasure itself is momentary. If I seek pleasure in immortal things the pleasure will certainly be lasting and enduring.

I give something to someone or even offer some fruits, flowers or any other items of offering to my deity. I take pride in this but forget what the best of devotees say while making a similar offering. They say, ‘twadiyam vastu Govinda tubhyam-eva samarpaye - it is your thing, O Lord and I hand it over to you only.’ Similarly when an oblation is offered to the holy fire it is specifically uttered, ‘Idam na mama - It is not mine, it is not mine.’ Thus it is incumbent on me to understand that I do not own or possess anything and everything belongs to Him. This understanding will enable me not to rejoice on acquiring anything and not to grieve on losing something. In other words I shall implement in letter and in spirit what has been written in the Bhagavad Gita that we should remain balanced in the face of all opposites like loss and gain, defeat and victory, grief and happiness.

All this will be possible only if I realize the true essence of the ‘Self’. This needs vigorous spiritual exercises. I have either to take to the path of knowledge, ‘Jnana-marga’, or I have to adopt practicing contemplation and meditation, ‘Raja-yoga’ or take to ‘Nishkama karma, the path of actions without an eye on its fruits. All this, I must admit, seems to me very difficult, easier said than done. Not that I have not tried to tread on these paths. In the bygone years of my life I have tried all these prescriptions many a time. Every time I found these practices onorous and difficult. I feel my acumen and capacity are limited enough to continue these exercises up to their logical end. So there is only one opening left for me and that is the path of devotion and surrender, ‘Bhakti-marga/Sharanagati’. This path is easy, workable and satisfying for me. All that I have to do is to leave everything to Him, who is omnipresent, omniscient and omnipotent. He will take care of me, my needs and my ambitions and why not? Has he not promised this in so many words in this shloka, ‘Tesham satata-yukhtanam yogakshema vahami-aham – I take full responsibility of all those who are attached to me all the time; I protect what they have and provide them with what they do not have. Taking care of me and my needs is not at all complicated for all that I need is to remain fit and healthy bodily, mentally and intellectually and alert spiritually. As for my ambition it is simply to know Him and to take care of that should not be difficult for Him in the least. After all I am not asking for the moon. I am only asking Him to reveal Himself to me so that not only do I realize that we are one but also I become one with Him. My desire is that ‘I’ and ‘He’ should go and only ‘I’ should remain.

Miracles

by T.N. Dhar 'Kundan'

Miracles happen and miracles are performed. These are performed by men of highest spiritual standing. Many of us may have read about many such miracles, many may have heard of them and many may have been witness to such miracles being performed. We have heard and read about innumerable miracles performed by great sages like Guru Nanak Devji Maharaj, Shri Rama Krishna Param hansa, Raman Maharshi, Swami Ram Tirtha and many others. This has not only enhanced their esteem in our eyes but also further strengthened our faith and belief in the Divine. I have not been very close to any of the contemporary saints to have been able to see these for myself. I have, however, heard and read about many such miracles performed by various saints and sages of Kashmir. Let me narrate some of these for ‘Vinoda, sukha, laabhaya’or entertainment, happiness and benefit of the readers.

Let me start with Alakheshwari Bhagavati Roop Bhawani. She was standing on the bank of a river and on the opposite bank was a Sufi Shah Qalandar. He called aloud to Bhawani in these words, ‘Ropi yor tar son karath’, Roopa! (literally silver), come to this shore and I will make you gold.’ Bhawani replied, ‘Tsuy tar yore mokhta krath’, better you come to this side I will make you a pearl (another meaning: I will liberate you.) Shah Qalandar was seen rowing a boat in which were seated Shiva and Parvati and crossing over to her side. Bhawani sent him back saying that that was not the desired way of crossing. Soon the Sufi saw a boat coming to his side, in which were seated Shiva and Parvati and he found that Parvati was none else than Bhawani herself.

Lalleshwari has the unique distinction of being not only the Valmiki of Kashmiri poetry but also a distinguished yogini of Shaiva order. Her sayings called ‘Vakhs’ are not only recited with reverence but are also sung in the beginning of various ragas of the classical music ‘Sufiana Kalam’ of Kashmir. Many miracles are narrated about her life. Once she went to visit the new born baby, who was later to become Nunda Rishi, the originator of Rishi order. His mother complained that the baby would not drink his mother’s milk. She held the new born in her lap and asked him this question: ‘Zena mandachhok na, chana kyaza Chhukh manda chhan – you were not ashamed to take birth, why are you ashamed of drinking your mother’s milk?’ The baby started sucking the mother’s breast instantaneously.

During the Pathan rule persecution of Kashmiri Pandits was at its peak. They would be tied, put into sacks along with heavy stones, carried to Dal lake at a place called ‘Batta Mazar’ or burial ground of Battas, and drowned there. A lady whose husband was taken for such drowning approached a saint known as Shakar Shah Mastana. She begged of him to save her husband. The saint wrote on a broken piece of earthenware this line: ‘gar chi hukme qaza ast, ba hukme Shakar Shah Mastana nav garaq shud, huma Brahman bar aayad. –Even if death sentence has been ordered, by the order of Shakar Shah the boat should sink and the Brahmin should be saved’. He asked her to drop this piece from the bridge into the river by which way the Pandit was being carried to the lake for drowning. She did the same and waited. When the boat reached the spot where the earthenware piece had been dropped, the boat capsized and her husband was thrown on to the bank. The same night the Pathan governor saw the saint riding a lion and he ordered him to stop this genocide or else he would meet a violent death. Next morning he ordered that this practice of drowning the Pandits be stopped.

Krishna Kar was walking on a footpath in a village when he found two bulls yoked with a ploughshare tilling the field without any person behind the ploughshare. He looked around and saw a young man sitting under the tree. He realized that it was a miracle being performed by him only. He took him away with the permission of his father and brought him to his locality, Rainawari. Later he came to be known as Meeshah. It is said that a huge boat laden with a load of food-grains was being towed up stream. The boatmen were singing a labour dirge, ‘Badshah padshah - Badshah Zainulabdeen is the King.’ Suddenly the boat got stuck up and would not move an inch. The boatmen approached Krishna Kar and asked his help. He came to know from them that a young man (Meeshah Saheb) was at the bank at that time. According to his directions the boatmen changed the wording and started singing, ‘Meeshah Padshah - Meeshah is the king.’ And lo and behold the boat moved with ease.

There are three prominent shrines in Kashmir, where there are springs wherein water sprouts forth only on specified dates. These are ‘Tri-sandhya, Rudra-sandhya, Pawana-sandhya”. It is said that Peer Pandit Padshah along with his disciples reached Tri-sandhya on a date when the water was not expected to ooze out. But he wanted to take this opportunity to have a dip in the holy water. He asked one of his disciples to see if there was water there. When he reported that it was stone dry, he wrote these lines on a piece of paper, Chi qudran Sonda-brari ran a aayad ba isteqbali Shahanshahi Reshi –It is surprising that the Sandhya has not come to greet this emperor of sages!’ When the piece of paper was thrown in the dry spring, gushing came the water for Reshi Peer and his disciples to take a holy bath.

Swami Shankar Razdan lived in Chattabal area of Srinagar. Maharaja Ranbir Singh and Maharaja Pratap Singh used to visit him occasionally to pay their respects. One day Maharaja Pratap Singh suddenly came to his house when he was having fever. When the arrival of the Maharaja was reported to Swami ji, he removed his blanket and had it kept in the corner of his room. While talking to Swami ji the Maharaja observed that there was vibration in the blanket. When asked what it was Razdan Saheb replied that he was having fever, which was kept under the blanket because of the Maharaja’s visit.

Pandit Madhav joo Dhar, the father and preceptor of Roop Bhawani sent a vessel ‘Degchi’ containing rice pudding, ‘Kheer’ to her in laws. The mother in law found it insufficient to be distributed to the neighbours and relatives. On Bhawani’s insistence, the pudding was distributed freely but it did not exhaust till the last family was served. Then there was the problem of sending back the brass vessel to Dhars. Bhawani solved the problem by throwing the vessel early next morning, down the river and asking it to reach Pandit Madhav joo, who would be offering ‘Sandya’ at the bank. The vessel reached him all right and he took it home. It is said that a similar miracle was performed by Bhagavaan Gopinath ji when at a shrine his sister had prepared food for five persons and Bab invited dozens of pilgrims to have food. His sister was perplexed but Bab asked her not to worry and continue serving the food to all the invitees. The food lasted till every single person had his meal.

At least twice did Bhagavaan ji order the clouds to go away without causing any rains, once when they were travelling in a boat ‘Doonga’ to Tulamula and the second time when they were on their way to Swami Amarnath ji for pilgrimage. He is said to have ordered in these words: ‘Hupaer Aeva, yapaer gatshiv – you have come from that side, now you go away from this side. Bhagavaan ji was instrumental in showing Sharika Bhagavati in the form of a girl to one of his companions at Hari Parbat and Shiva and Parvati at the shrine of Swami Amar Nath.

Reshi Peer’s mother was very old and one day when a neighbor was going for a pilgrimage to the holy Ganges, ‘Ganga-jatan’, she expressed a desire to her son that she would also like to go for a dip in the holy waters on the auspicious day. Reshi Peer asked her to give her gold bangle. She gave it to him and he in turn handed it over to the neighbor to be immersed in the water there. On the auspicious day of ‘Ganga-aetham’ he took her to the bank of the Vitasta and asked her to take a dip. While she was taking a dip her gold bangle came floating on the waters and she held it in her hand. The waters of the holy Ganges had thus been brought into the Vitasta by the miraculous powers of her son, a sage of very high order. Peer Pandit Padshah, as he was popularly known, was once invited by a Muslim cleric to have a non-vegetarian meal with him and a group of some distinguished persons. He agreed on the condition that nobody should have tasted a morsel out of the cooked dishes before the invitees. When the food and some choicest dishes were served and the guests were asked to uncover the plates, everything cooked assumed its pre-cooked state. The rice was raw, vegetables were green and the chickens were alive. To the amazement of everyone present they found that one chicken was limping. The cook had tasted one chicken leg and the condition laid by the sage had been violated.

One of the Pathan governors was named Jabbar. He was a tyrant and during his time Hindus were persecuted badly. He was once told that Hindus consider it auspicious if it snows on Shiva-ratri while they propitiate the deity. He scoffed at it and said that there was no point in it since the festival was celebrated in winter when it rains and snows in Kashmir. As a vengeance he ordered Hindus to celebrate the festival in summer. It is recorded that while the puja of Shivaratri was on, clouds gathered and it did snow briefly. The public ridiculed the governor for this folly in these popular songs, ‘Wuchhton yi Jabbar janday, haras banovun vanday – Look at this wretched Jabbar, due to him the summer was converted into winter.’

Strange are the ways of the Divine and strange are the ways of those who have become one with Him.

Need For A Guru - Importance of a Preceptor

by T.N. Dhar 'Kundan'

There is a saying in Hindi ‘Guru bin gati nahin – Achievement is not possible without a guru’. This statement needs a detailed analysis and examination, particularly because there have been many great spiritual luminaries who were known to have achieved highest levels without the guidance of a preceptor. On the other hand there have been saints and sages like Swami Vivekananda, who were guided to spiritual heights by their preceptors. In Indian mythology and tradition mention is made of many such spiritual giants, who are said to have surpassed their preceptors. There are instances where some fortunate ones have got messages in their dreams or even otherwise, about the persons, who were going to be their preceptors. Also there are cases where some gurus have got the divine direction to guide a particular person. Thus there are illustrations supporting every possible situation. A seeker can find a suitable guru for himself, someone could be ordained to guide him, he can get an indication about whom he should approach for spiritual guidance or he can go on his own on the path of spirituality.

Even in the case of mundane and worldly matters one may like to benefit from the advice of the seniors and the knowledgeable, take lessons from the experiences of others or use one’s own wisdom and judgment and experiment with life for one’s own self. In the day-to-day life we see that the so-called educated persons are not necessarily wise or well behaved. Similarly those who are unlettered are not, ipso facto, unwise and uncultured. Life is a great teacher and by its nature it is a series of experiences, which teach us the facts of life and guide us how to conduct ourselves. We are social animals and, therefore, form small groups, communities and societies within the framework of the country in which we live. Our country also models and remodels itself within the global compulsions in order to prove its credentials as a worthy member of the international family. A society learns from other societies, a country benefits from other countries and likewise an individual makes the best use of the experiences of other fellow individuals. Thus in mundane matters there are teachers who guide us either directly or indirectly, either knowingly or unknowingly. The question that arises is whether the same is the case in the spiritual world as well. Do we benefit from other’s experiences?

Spiritual experience and seeking are by the nature of these things strictly a private affair for every one of us. Those who are in the process of seeking may be able to roughly describe the methodology adopted by them but they are completely unable to describe their actual achievements, not even the interim milestones. Therefore our benefiting from the experience of others is absolutely out of the question. Even our preceptors give broad guidelines and tell us how to proceed with our spiritual experience. This is definitely based upon his or her own experience, for it is said that no one can lead us on a path, which he himself has not traversed. Thereafter we have to do the needful ourselves and benefit from our own experiences and experiments. This leaves us with one more question and that is in which cases do we need preceptors and their guidance.

According to the Indian tradition spiritual experience can be of four different types depending upon which of the four ways we adopt for achieving the goal, ‘Jnana’ or knowledge, ‘Karma’ or actions, ‘Bhakti’ or devotion and ‘Dhyana’ or contemplation. A teacher or a guru is definitely needed if we tread on the path of knowledge because there has to be some body knowledgeable, which can impart that knowledge to us. It is then up to us to assimilate that knowledge and also if possible and required, to improve upon it. Similarly a teacher is needed and indeed useful to guide us on the path of action. He can put us wise as to what should and what should not be done. Having selected the action he can again tell us how to go about executing it. Thereafter it is up to us how dexterously we undertake the action and how well we execute it in order to achieve the desired results expeditiously and in full. Likewise for contemplation a teacher is needed to teach us the technique and the methodology. Actual contemplation is for us to undertake. If we are able to perfect the technique we will surely achieve the target and get illumined in the shortest time possible. Of course all these things in these three areas can alternatively be learnt from an in depth study of the scriptures as well. Even when we do take refuge at the feet of a guru, the guidance received from him can further be supplemented by a detailed study of the scriptures. In fact the guru can be instrumental in helping us select and choose the useful passages and portions of the relevant literature from the vast treasure available to us.

Devotion, however, is a different cup of tea altogether. Once we are deep in love with our chosen beloved and have unflinching and unwavering faith and confidence in him, we really do not need any teacher. Meera and Surdas, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu and their ilk did not need any Guru. In fact this chosen beloved can be our preceptor itself. Once we are madly in love like the Gopis were in love with Shri Krishna, where is the need for a teacher? Love is not a thing that can be taught, faith is not a thing that can be created and confidence is not a thing that can be dictated. All these traits either we have or we do not have. We may not have these but may imbibe in course of time. Devotion in fact is needed in all the different paths adopted by different seekers for their spiritual elevation. We have to be devoted to the knowledge that we seek in the path of ‘Jnana’ or knowledge. This devotion will take us nearer to the Supreme Truth. We have to be devoted and committed to the actions and deeds that we undertake. The devoted actions only will illumine our spiritual path. Devotion in contemplation will ensure concentration and hasten the entire process for the spiritual elevation. Without due devotion no path will lead us to our desired goal.

Devotion presupposes love, faith, confidence and complete surrender. Even those seekers, who take to other ways of seeking God, reach a point where they have to surrender. This surrender ensures the grace of God without which fructification of no effort is possible. Spiritual seekers treading on the path of knowledge and action use their faculties of reasoning and logic, which give them power of discriminating between transient and eternal and take them a long way towards their goal. Thereafter they have to take recourse to faith, which takes them to the goal itself. While in the first leg of their spiritual journey they may find taking someone as their guru useful and beneficial, in the second leg no guru would be needed. Guidance of a guru is needed in the first instance but later no guru is required. Love is actually in the nature of an instinct. It chooses its beloved itself and then sacrifices everything including personal comforts for his sake. A seeker walking on the path of devotion or ‘Bhakti’ surrenders before his beloved from the beginning of his spiritual journey, which travellers on other paths have to do in the end. Goal, however, is common for all of them as Pushpadanta says in his ‘Shiva Mahimnastotra’: ‘Riju kutila nana pathajusham nrinam-eko gamyah tvam-asi payasam-arnava-iva – For people treading different paths, straight or crooked, You (Shiva) only are the goal just as the ocean is the goal for all rivers flowing into it’.

Having said that, we cannot deny that a guru may not necessarily be required to guide or lead on the path of ‘Bhakti’ or devotion, yet it cannot be completely ruled out that he can be a source of inspiration in this case also. There have been cases where a person, an ordinary worldly person, has reached a turning point in his life from where the direction of his life has taken an about-turn with the result that his life has changed altogether. At this point something or someone has definitely inspired him, visibly or invisibly. There has been change in the life of Valmiki, Tulsidas and host of other great men and they have taken to a life of highest spiritual character, after this change. We see, even in the contemporary times, great orators addressing gatherings of thousands of people and narrating the stories from Ramayana, Shrimad Bhagawat and other sacred texts. All the assembled persons, men and women, listen to these stories with devotion and many of them are inspired to take to the path of ‘Bhakti’ in all seriousness. If these noble men are able to inspire some people in these collective gatherings, certainly preceptors can influence and inspire individuals also in their private sittings to tread on the path of devotion.

Devotion is a straightforward affair. It needs no technique or methodology. It only needs unflinching love, dedication, trust and confidence coupled with complete surrender. On this path the ego, the notion of ‘I’ vanishes. The devotee realizes that the Divine only does whatever takes place and he remains devoid of the notion of doer-ship ‘Kartritva’. The devotee understands that the Divine only enjoys whatever he seems to be enjoying visibly and thereby he shuns the notion of enjoyer-ship, ‘Bhoktritva’. Similarly he believes that the Divine only possesses whatever he is seen to be possessing and thus he gives up the pride of possession and ownership, ‘Mamatva’. Whenever he offers anything to anyone he utters this statement in all humility, ‘Tvadiyam vastu Govinda tubhyam-eva samarpaye – O Lord, this is all yours and is being offered to you only’.

Guru is a Sanskrit word, which can mean a teacher, a guide, an elder, an enlightened one or a preceptor. Some scholars have interpreted it as a word combining two syllables, one meaning darkness and the other remover. They conclude that a Guru is one who removes all the darkness of ignorance. Be that as it may. A question is often asked whether a Guru is a must and whether every one of us needs a Guru. Our experience in both mundane and spiritual fields shows that there have been people, who were very knowledgeable but with the guidance of one or the other Guru. Also there have been equally enlightened persons without any Guru or what we call self-made persons. Thus to give a clear cut answer to this question about inevitability of having a Guru is well nigh impossible.

Arthur Osborne has observed in the biography of Raman Maharshi that ‘the term Guru is used in three senses. It can mean one who, although he has no spiritual attainment, has been invested (like the ordination of a priest) with the right to give initiation and upadesa. He is often hereditary and is not unlike a family doctor for spiritual health. Secondly, the Guru can be one who, in addition to the above, has some spiritual attainment and can guide his disciples by more potent upadesa (even though the actual practices enjoined may be the same) as far as he himself has gone. But in the highest and truest meaning of the word, the Guru is he who has realized Oneness with the Spirit that is the Self of all. This is the Sadguru.’ He has quoted the Maharshi as having described a Guru as follows:

“The Guru or Jnani (enlightened One) sees no difference between himself and others. For him all are Jnanis, all are one with himself, so how can a Jnani say that such and such is his disciple? But the un-liberated one sees all as multiple, he sees all as different from himself, so to him the Guru-disciple relationship is a reality, and he needs the Grace of the Guru to waken him to reality. For him there are three ways of initiation, by touch, look and silence.”

In reply to a query whether he had a Guru or not, the Maharshi is reported to have said that ‘Guru is God or Self. First a man prays to God to fulfill his desires then a time comes when he does not pray for the fulfillment of a desire but for God Himself. So God appears to him in some form or other, human or non-human, to guide him as a Guru in answer to his prayer.’ On yet another occasion he is said to have clarified that ‘a Guru can be outside yourself or within yourself. Two things are to be done, first to find the Guruoutside yourself and then to find the Guru within.’ These statements assert that there can be a Guru, who may not be in any human form and yet may give initiation and Upadesa to his disciple.

We know from the Shrimad Bhagavad Gita that three things are needed for us to benefit from a Guru. These are ‘Pranipata’ or submission, ‘Pariprashna’or enquiry and ‘Seva’ or service. As regards submission, Arthur says that ‘submission to this Guru is not submission to any outside oneself but to the Self manifested outwardly in order to help one discover the Self within.’ He has quoted the Maharshi as having remarked thus: ‘The Master is within; meditation is meant to remove the ignorant idea that he is only outside. If he were a stranger whom you were awaiting, he would be bound to disappear also. What would be the use of a transient being like that? But as long as you think that you are separate or are the body, so long is the outer Master also necessary and he will appear as if with a body. When the wrong identification of oneself with the body ceases the Master is found to be none other than the Self.’

The philosophy behind all this discussion is that the Self, the Preceptor and the God are actually one. This stands to reason when one believes and perceives that God pervades everything and that everything is the manifestation of the God. This is the high point of ‘Advaita’ or non-dualism. We have a rich heritage of saints and sages. If we go through their lives on this planet earth we come across divergent situations and happenings. There are instances where some of them did not have a Guru as such in a human form. Those who had too present a variety of pictures. In some cases a Guruhas travelled miles in search of his disciple and having found him has initiated him and given him upadesa. In other cases a disciple has traversed long distances and has run from pillar to post in search of his Guru. After finding him he has surrendered and prostrated before him and sought spiritual guidance. Some luckier ones have chanced to come by a Guru, who has readily taken them into their tutelage. In many cases a Guru is reported to have tested the acumen, sincerity and resilience of the disciple before accepting him as his ‘Shishya’, or disciple. In some cases even the disciple has examined the competence and the spiritual level of his Guru before handing over the reins of his spiritual journey to him. There are a few odd cases where a disciple was refused acceptance by a reputed Guru and yet the disciple made him his preceptor in absentia and received initiation by connecting with him through his conscience.

The Guru gives upadesa and initiates the lucky one whom he takes into his tutelage. It is believed that there are three modes of initiation, by touch, by look and by silence. A bird that needs to sit on its eggs in order to hatch them denotes initiation by touch. A fish, which needs only to look at its eggs to thatch them, represents initiation by look. A tortoise typifies initiation by silence, as it needs only to think and the eggs get thatched. We have come across a variety of different ways of initiation by touch. A Guru may put his hand on the disciple’s head. He may touch his forehead or his cheek. He may strike him with his toes gently. He may touch an item and then make the disciple touch the same or cause him to touch the same item and the process of initiation is complete. The initiation by touch is also known as Shaktipat or descent of power. Initiation by look is a straight eye contact whereby theGuru transmits the spiritual light to his Shishya by looking into his eyes. In this case the latter is mesmerized as it were and for a moment goes into the state of trance. In the case of the initiation by silence what happens is that the Guru and the Shishya both come on to the same wave length of thought and a spiritual connection is formed.

Every one of us refers to himself as ‘I’. He has three aspects, being (Astitva), doing (Kartritva) and enjoying (Bhokhtritva). His being is called Sat in our scriptures. This is his existence, which he is required to recognize. His doing has to be for the good and benefit of all and for that his Chit or consciousness is there to guide him. Then there is his enjoying this has to be detached as has been rightly and explicitly stated in the Upanishad, ‘Tena tyekhtena bhunjeethah – thus you must enjoy everything with an attitude of ‘Tyaga’,which has been defined as not worrying about the fruit. This will give himAananda or bliss. The three together ‘Sat, Chit, Aananda’ form the description of the Supreme God. These three correspond to another set of three words describing Him, i.e. Satyam or certitude, Shivam or benevolence andSundaram or aesthetics. Certitude denotes existence (for only that which exists can be true and certain), benevolence refers to noble actions and deeds and aesthetics causes bliss. Now it is the guidance of a Guru that shapes these three aspects in us, viz. our personality, our deeds and our bliss.

It would be interesting to narrate some known facts here about various preceptors and how they approached or were approached by their disciples. Take the case of Pandit Krishna Kar. He was ordained by the goddess to guide Rishi Peer. He went to his house and not finding him there (he had gone to Hari Parvat), smoked from the hubble-bubble kept at his house. He left a word with his mother that Rishi Peer should smoke from the same smoking implement. When he came home, he did as was told and got theupadesa. Alakheswari Roopa Bhawani had her own father as her Guru, who not only gave her lessons in scriptures but also led her on the path of supreme enlightenment, which she has referred to as ‘Parama Gati).Similarly Shri Rama Krishna was approached by his would be Guru and initiated as ordained by the goddess. He, in his discourses, used to liken money with fire. In order to test his statement Narendra Nath, before he became Swami Vivekananda, hid a currency note under the seat of Shri Rama Krishna. When he came and took his seat, he immediately stood up shouting ‘fire, fire!’ Then smilingly, he revealed that this must be the handiwork of Narendra. Anandamayi Maa was initiated by her Guru and in due course after that she initiated her own husband. Shri Raman Maharshi said that a Guru could be impersonal as well since he believed that the Self, the Guru and God, all were one and the same. Bhagavaan Gopinath, when asked about his Guru, referred to the Bhagavad Gita and said any one of the seven hundred and odd Shlokas of it could be the Guru. Naturally, therefore, he was also referring to an impersonal Guru.

After giving it a thought we feel that every seeker is a disciple in his own right and has a Guru, personal or impersonal. The guru evaluates his acumen, capacity and spiritual level and accordingly suggests a path for him to tread upon. The disciple also seeks a Guru as per his tastes, liking and inclination. It makes easier for him to chalk out a suitable path for himself. There have been cases where a disciple has changed the course of his journey midway after realising that the path he was on was not suitable for him, was difficult for him or was more time consuming. Some seekers progress step by step and rise by stages. For them Shri Gita says, ‘Aneka janma sansiddhah tato yanti paran-gatim – these people seek perfection life after life and then attain the supreme status.’ Others jump over many stages and reach the destination in lesser time. According to Kashmir Shaiva Philosophy there comes a stage when they realise that the seeker and the sought after are one and the same. Even then there is an element of dualism at that stage too since the seeker and the sought after are considered as two different entities. They raise themselves further up and get merged with the Supreme and then alone the stage of perfect non-dualism is reached.

Sons of Immortality

by T.N. Dhar 'Kundan'

Even a cursory look at the life and its reality shows that while the frame is mortal, the essence hidden inside is immortal. Perhaps, that is why the Vedas enjoin upon us to be the sons of immortality, ‘Amritasya Putrah’. While the ultimate aim for us should be, as Swami Vivekananda says, to rise from animality to divinity, it seems necessary for us to take the first step and try to become humans first. For this to achieve, it is necessary for us to imbibe certain qualities. Shri Gita has prescribed more than two dozens of specific qualities for a person to be of the divine nature. About half a dozen of these are basic qualities, which make us humane and civilized. The rest are perhaps on a higher level and can be aspired subsequently.

To be virtuous is a basic human trait, and perhaps a desirable duty too. Virtue is called ‘Guna’ in Hindi/Sanskrit. Our scriptures say that virtue is respected and worshipped everywhere, ‘Gunah sarvatra poojyante.’Therefore, it is enjoined upon us to earn virtues that will enable us justify our being human kind, ‘Tasmat gunani arjadhvam.’ It is not a debating point that we should be good human beings, good members of a society and good citizens of a nation. That makes it a paramount necessity for us to imbibe virtues and acquire qualities. Let us enumerate these qualities and identify the value that these impart to us. Our scriptures are replete with discussion on these virtues and the saints and sages, who have appeared on this planet Earth from time to time, have also thrown light on these qualities in their discourses, writings and sermons.

In olden days when a student had completed his studies a ‘Dikshanta’ceremony was held, which may be viewed as the modern day convocation. On this day, before the student entered the fray of active life, he was administered certain oaths to guide him in the conduct of his life’s struggle and make him tread on the path of righteousness. The first lesson given to him was ‘Satyam vada’, or to be truthful and practise truth. The second direction given to him was ‘Dharmam chara’, or to do his duty and be righteous. The third one enjoined upon him to continue learning and teaching, ‘Swadhyaya-pravachanabhyam na pramaditavyam’, or do not show laziness in self-study and transmitting your knowledge to others. This was followed by a prescription for the code of conduct. ‘Matri devo bhava, pitri devo bhava, acharya devo bhava, atithi devo bhava – Show due regard and respect to your mother, father, teacher and the guests and treat them as gods.’ These qualities if imbibed in thought, word and deed, make us humans in right sense of the term. These lead us eventually to immortality and make us ‘Sons of Immortality’.

Let us examine the qualities prescribed by Shri Gita for us to be divine. We can cull out a few qualities out of this long list, which we think are essential for us to deserve being called humans. Once we adopt these, practise these and make these part and parcel of our life-styles, we can then proceed to adopt the remaining qualities in order to go higher and higher on the spiritual ladder. The basic qualities in the first batch could be listed as Truth, Compassion, Gentleness, Fearlessness, Uprightness, Non-violence, Modesty, Steadiness, forgiveness, Fortitude, and freedom from anger, malice and pride. Coming to think of it, these qualities are inclusive, interdependent and interlinked. The quality of truth is the foundation on which the edifice of all other qualities is built.

If we are true, we will, ipso facto, be fearless, upright and steadfast. The truth will give us fortitude and modesty. These in turn will make us non-violent, and free from anger, malice and pride. All this will help us develop an attitude of compassion towards our fellow men and other creatures and we shall be humane, understanding and loving towards one and all. Love, as we know, is the corner stone of human bondage and this binds us together and brings us closer to each other. Nature has given us humans a heart, which is the centre of love, a spring of compassion and kindness and an instrument of feeling and caring. Reaching this place where we are endowed with these basic qualities is not an end in itself. It is only a station en route. Many of us reach this place and knowingly or unknowingly treat it as the destination and feel satisfied. But there are blessed ones, who know the reality that there is still a long way to go. They keep their journey on and tread upon a higher plane of spiritual quest. They start imbibing the remaining qualities in order to become imbued with divine traits. This endears them to Almighty, who assures them in these words, ‘Sa me priyah –He is dear to Me.’

The qualities that we have to acquire on the higher plane of spiritual quest are Self Control, Renunciation, Tranquility, Vigour, Self-study, Balanced demeanor, aversion to greed and fickleness, Absence of the habit of finding fault with others and a well planned ‘Jnana’ and ‘Yoga’. Let us take the last one first. This quality brings equilibrium in our Knowledge and Actions. ‘Jnana’is academic and theoretical science and ‘Yoga’ is its application. Once we create a balance in what we know and what we do, we rise further up in the ladder of spirituality. With all the qualities enumerated in the previous set, we are still living on the plane of ‘Gunas’ or the attributes. No doubt we are endowed with the attribute of light ‘Satva-guna’, and not those of passion and darkness, ‘Rajoguna, Tamoguna’ yet our goal has to be to rise to a plane devoid of all the three attributes. At this plane we are fully in control of our selves, we are firm and steadfast, we have no greed nor have we any habit of finding faults with others. Kabir has said about this situation in these words, ‘Bura khojana main gaya, bura mila na koi, jo man khoja aapno mujh sa bura na koi – I went in search of a bad person but could not find one. When I examined my own self I found that no one was as bad as me’. This gives a clear hint that we should engage in self-analysis and try to know the self. For this we must shun greed and fickleness, adopt a balanced attitude, enjoy with a sense of renunciation and be full of vigour and tranquility. ‘Jnana’ or knowledge enables us to experience the truth of existence or ‘Sat’.‘Yoga’ on the other hand enables us to merge with the universal consciousness or ‘Chit’. Having thus realized the subtle truth, we are prone to surrender before the Supreme. We become an embodiment of love and attain supreme bliss, ‘Aananda’, a position which has no antonym or opposite. That is the destination every seeker craves for and endeavours to attain. At this point the seeker says in the words of Kabir, ‘Jab main tha tab ve nahin, ab ve hain main nahin, prem gali ati sankari, ya mein do na samahin – When I was there, He was not; Now He is there I am not. This lane of love is too narrow to accommodate two at a time.’

We are always advised to realize ourselves. We are told that our true self is not the body, mind and the intellect. Our essence is something beyond these and that is what we need to identify, seek after and realize. While this stipulation is completely true, yet we should not under-estimate the importance of these recognizable items of our existence. Our body is a vehicle, which has various senses of knowledge, deeds and perception. It is through these that we function, act and react. Our mind is a vehicle of thought. Our heart is a vehicle of feeling and compassion. Our intellect is a vehicle of discernment, discretion and discrimination. It is through these vehicles that we function and put into practice the faculties of virtues and qualities, which we are endowed with. It is because of this fact, perhaps, that there is a saying in Sanskrit, ‘Shariram-aadyam khalu dharma-sadhanam –Body is the foundation stone of executing our duties.’

It is clear from the foregoing discussion that it is in the nature of things that we should be virtuous. Every one of us has an element of all the three attributes of truth, passion and darkness. The quality of a person depends upon which of the three elements is prominent and predominant in his personality. A person with the attributes of truth and light predominant in his nature can be taken as a true human being. Once a person rises above these attributes of lower plain and is endowed with the qualities of higher plain, he can be treated as a divine person. Once he transcends all the attributes, he realises his self, his individual consciousness gets merged with the universal consciousness and he attains a stature where he is called the son of immortality or ‘Amritasya Putrah.’

Conversion

by T.N. Dhar ‘Kundan’

Nobody can deny the fact that faith is one’s own private affair. Normally a person owns and adopts the faith of the parents who have given him birth. Of course in cases where the father and mother belong to two different faiths, it is open to their child to adopt either of the faiths. In later years a person may decide to get converted to a different religion and adopt a faith of his choice different from the one he was pursuing from his birth. How far this conversion is logically correct and justified is a matter of debate. But one thing is very important in this regard and that is the reason for conversion. If we take statistics of conversions in an area over a period of time we will see that the higher percentage of conversions is because of coercion, force, inducement, financial benefit by way of employment etc; and marriage. Cases of conversion on principle of religion and spiritual advancement are rare. A study of the history of the world will bear witness that the conversions have largely been the result of coercion, inducement and the threat to life and honour. Be that as it may.

In a recent case the High court of Delhi made some very important observations in this regard. It said that the primary reason for conversion ought to be spiritual advancement and to seek God from another platform. It went on to say that ‘unfortunately today proselytization is being done for reaping benefits and in some cases to manoeuvre the law.’ It follows that while it is the privilege of an individual and his right of freedom to profess any faith to get converted in order to be able to get spiritual advancement or to try and seek God from a different platform, no civilized society can allow conversion to reap benefit or to circumvent law of the land. Nor can conversion be allowed through coercion, inducement or threat to life and honour.

I was once directed by H.H. the Shankaracharya of Shringeri to translate a book titled ‘Dialogue with the Guru’ written by one Mr. Iyer, into Hindi. The book contains an anecdote, which goes like this: A European gentleman, Christian by birth, was so impressed by the discourses of the then Shankaracharya that he volunteered to get converted to Hinduism. He expressed this resolve to the Acharya, who was quick to enquire, ‘why?’ The gentleman replied, ‘in order to seek God’. His Holiness asked, ‘who has given you birth in a Christian family? The answer is, the same God, who you want to seek. That means you want to seek the same God, whose discretion of giving you birth as a Christian you are challenging. Is it not a paradox?’ The Swami went on to add, ‘there is no need for you to get converted since you are already a Hindu; the Hindu faith is all embracing with a world view. It is without a beginning, without an end and includes all shades of faiths.’ This raised a question in my mind whether we are entitled and justified in changing the faith of our birth for any reason whatsoever. I am still trying to find an answer to this question.

I am, however, aware of the social changes that have taken place over the centuries. At one time in India marriages between different castes, ‘Varna’were largely prohibited. The progeny of mixed marriages was called ‘Varna-sankara’ or cross breed and was looked down upon since he would ignore his ancestry and his ritualistic responsibilities towards the dead ancestors. Even so normally he would be counted in the caste of his father. In India, there was only one faith practiced throughout the length and breadth of the country and that was ‘Sanatana Dharma’ and, therefore, even in the case of the off-shoots of the mixed marriages, the faith was the same. The question of the change of faith did not arise. In due course of time two heterodox faiths developed in the form of Buddhism and Jainism but these were treated as only off-shoots and extensions of the mainstream faith ‘Sanatana Dharma’and following either of these faiths did not amount to conversion or change of faith. Buddha is regarded as the ninth incarnation of Vishnu. It is an open secret that the Buddhism, which originated from India, did influence first the faiths and doctrines prevalent in Burma, Sri Lanka, Tibet, China and Japan and in due course those in other countries of the East. It is equally known that the non-dualist philosophy of India also influenced the Sufi cult of the Middle East. Soon the two religions, Christianity and Islam which originated from there, began spreading in various continents and also spread Eastwards. This gave rise to changing of faiths, which is known as conversion. History is replete with the instances of mass conversions, systematic conversions over a period of time and forcible conversions after conquests of territories. There are also instances of religious intolerance, whereby people of one faith not only consider their faith as the only true faith but deny the people following other faiths even the right to live and to exist.

Times have changed. The countries of the world have come closer and the world has become a global village. There is so much inter-dependence and interaction socially, economically and politically that the differences of faiths practiced by various groups of people have gone into background. Practising a particular faith has been relegated to the privacy of one’s personal life. The need of the hour is not only co-existence but mutual respect and acceptance of the validity of all faiths. In the theocratic countries where one faith is given official recognition by the government, respect for other faiths has to be enforced. In secular polities the best tenets of all the major faiths of the world should be taught through the school curriculum. The ideologies may be different in the matter of spirituality, in relation to the Divine, His relationship with the creation and the ways and means of seeking Him and His position in our lives. Yet there are similarities in the mundane aspects and prescriptions in different faiths. These include the tenets of truth, morality, behaviour , ethics and the like. This similarity can and should be highlighted for the benefit of the mankind at large. Moreover, practice of a faith and adoption of a method of seeking spiritual advancement goes with personal qualities of the seeker, his capacity, tenacity, acumen, receptivity, inclination and his bent of mind as also likes and dislike. So no faith can be thrust upon him by coercion or compulsion.

Economic situations have played havoc in the societies. These days, the faiths and castes, which used to be of paramount importance in the past, have lost much of their sheen. Class-distinction has taken the place of caste and faith distinctions. In Hindu societies there was anger in the so called lower castes because of the treatment meted out to them by the so called upper castes. (The division was supposed to be on the basis of characteristics and deeds, ‘Guna-karma vibhagashah’ and not on the basis of birth). This resulted in large scale conversion from Hindu faith to other faiths. To their chagrin, however, the neo converts found that the discrimination still persisted even after their change of faith. The people of higher economic class in the society of the adopted faith looked down upon them in the same manner as they were looked down upon in the society of the previous original faith. Many of them wanted to get re-converted because of this bad experience but the religious rigidity and conservatism prevalent in Hinduism did not allow this to happen with the result that they got alienated and inter-society and intra-society conflicts increased.

There is no doubt that conversions world over were most successful among the tribes, who were primitive yet had their own form of rituals, set of beliefs and ways of religious celebrations. They were lured into conversions because of the glamour and economic advantages. In the process they lost their distinct character as tribes. The simplicity and straightforwardness of their life style were replaced by greed, ostentation and duplicity. No doubt economic packages for them were needed that would give them the comforts and facilities of the modern times. But all the same there was also a need to safeguard their distinct character and cultural uniqueness, which includes their faith. Large scale conversions played havoc with them and they lost their roots and moorings. There are certain organizations active in the field working for restoration of their original faiths, character of their culture and pristine purity of their faith while simultaneously ensuring that the fruits of advancement of the modern times are not denied to them. These efforts are laudable if these are without any political motive or sectarian aggrandizement, and are purely on anthropological considerations. There is also a need for enactment of laws to put a full stop to un-ethical and fraudulent conversions by coercion and threat to lives.

Hinduism

by T.N. Dhar ‘Kundan’

The nomenclature ‘Hinduism’ is a misnomer because there is no religion as Hindu religion. Since, however, people who have visited India or read about it call our faith as Hinduism, we are obliged to use this term. It appears that when the foreign travelers, tradesmen and invaders came to India they reached the shores of the mighty Indus called by us ‘Sindhu’. They called us by this name, which corrupted from Sindhu to Hindu and they called our faith and religious practices as Hinduism. The correct nomenclature for our faith is ‘Sanatana Dharma’ or the set of beliefs that are eternal in character. The foundation of our faith is the Vedas, which we call ‘Apaurusheya’ or the doctrine not formulated by any human being. This is obvious because every principle, every doctrine, every canon and every law emanates from the Divine. These laws are perceived by enlightened people referred to as ‘Rishis’ or sages, who were both men and women.

These laws were revealed to these sages from time to time, mostly in the form of ‘Mantras’. It is because of this that the sages were called ‘Matra-drashta’ or seers of these laws and canons. A stage came, when it was found necessary to arrange these laws in a proper order and compile them on the basis of their purport. This job was done by a sage who came to be known as Vyasa or the one who arranged these revelations in an order. He put them in three volumes and named them as ‘Rig Veda Samhita’, ‘Yajur Veda Samhita’and ‘Sama Veda samhita’. The three together are called ‘Veda Trayi’. Another sage by the name ‘Atharvana’ compiled the canons and principles relating to the mundane aspect of human life and this became the fourth Veda named as ‘Atharva Veda’.

Now what is this religion (if we may call it so) all about? Since it is without a beginning and without an end, it has evolved over many millennia. Naturally, therefore, it comprises many view-points, many shades of opinions and a variety of prescriptions of ways and means to attain the Supreme Truth. Even so there are certain fundamental principles of this faith and some interesting features, which are noteworthy. It is not confined to one revealed or holy book. There is no human being who may be said to have originated this faith. It respects all opinions and holds them as valid and relevant. It does not consider one path of seeking the truth as superior to another nor does it consider only one way as correct and the rest as false. It believes in only one God but worships Him in different forms and with different names.

There are four important routes to attain the Supreme. The first is through knowledge or ‘Jnana-marga’. When we take this route we have to acquire knowledge of the self and everything around us, determine the relationship between the two and thereby attain the Supreme Truth, which some identify as God realization. The second route is through action or ‘Karma-marga’.While taking this route a seeker has to execute all his actions and deeds with a detached mind, without an eye on the fruits. The seeker has not to get attached and has not to worry about the fruit of the actions. He has to have a balanced attitude to success and failure, gain and loss, pleasure and grief and other opposites. This attitude leaves him unscathed like a lotus in a pond and helps him reach the pinnacle of spirituality. The third route is perhaps the most popular route of all, that of devotion or ‘Bhakti-marga’. Here the devotee is madly in love with his deity and, therefore, surrenders unto him completely. He leaves the boat of his life in his charge and has no worries. The Almighty according to His own promise, takes care of such seekers, He provides them with what they do not possess and also protects all that they do possess. The fourth route is more sophisticated, complex and consequently practiced by a chosen few. It is called ‘Raja- Yoga’. This route involves contemplation of the highest order that leads to God realization or Self realization, depending on whichever way one looks at it. For, ultimately the seeker and the sought do get merged into one and the principle of non-dualism is experienced.

This religion is vast and varied. The Divine is viewed, perceived and worshipped in different forms as also formless, ‘Saakaara/Niraakaara’, with attributes and without attributes, ‘Saguna/Nirguna’ and in absolute form as Shiva as also His Energy aspect as Shakti. Different aspects of the Divine are conceived as different deities and worshipped as such in different forms and propitiated for the grant of different boons. Saraswati is worshipped as goddess of knowledge. Laxmi is regarded as the goddess of wealth. Kali is the goddess of eternal time. Brahma is regarded as the creator, Vishnu as sustainer and Rudra as the destroyer. They are not different gods but different aspects of the one and only Supreme Divine. Those who consider Him as formless perceive Him in a variety of ways, as Truth, Universal Consciousness, Infinite Existence, boundless Bliss or dazzling Beauty and the like. Those who see Him with form give Him a form of their liking and then worship Him and his ‘Murti’. They sometimes put a bow and arrow in His hands, sometimes a mighty mace or a trident and some other times a loving flute.

Apart from the basic beliefs in one God, virtue and righteousness, purity and piety a Hindu believes in spirituality, transmigration of soul and detached actions. Transmigration of soul and rebirth is universally accepted except by the religions that have emanated from the Middle-east. Even philosophers like Pythagorus (whose name incidentally means ‘a person who knows his previous birth) have conceded that there is this phenomenon in this world wherein a soul is embodied time and again. The other important tenet of Hindus is their belief in ‘Karma’ or action. They believe that the actions of the previous births shape our destiny in this birth but one can reshape one’s destiny for good or for bad by the actions of the present birth. And it is further believed that detached actions can liberate a person and he will attain emancipation.

Hindus believe in one God but multiple ways to reach Him. The seekers are likened to small rivulets and God to an ocean. These rivulets take different routes, straight or zigzag but ultimately find their way to the mighty ocean. Likewise the seekers adopt different routes, indirect or direct according to their respective tastes, but attain the same Divine, who pervades everything in this universe. So far as Hindu’s relationship to other human beings and other species is concerned, they believe the whole universe to be one family, ‘Vasudaiva kutumbakam’. This is further clear by their daily prayers like, ‘Sarve Bhavantu sukhinah – Let everyone be happy’, ‘Ma vidvishavahaiy – Let us not hate anyone’, ‘Tan-me manah shiva sankalpam-astu – Let my mind be full of noble resolve’ and ‘Yatra vishvam bhavati eka needam – The whole world should become a nest to give shelter equally to everyone’.

Truth, righteousness and respect for elders are the corner stone of this religion so far as the mundane aspect is concerned. It is clear from these vows taken by a student at the time of the convocation called ‘Dikshanta samaroha’ or celebrations at the culmination of the studies. ‘Satyam vada’, ‘Dharmam chara’, Matri devo bhava’, ‘Pitri devo bhava’, ‘aacharya devo bhava’ and ‘Atithi devo bhava’ meaning, ‘Speak the truth’, ‘Be righteous and do your duty’ and ‘treat your mother, father, teacher and the guests with reverence.’ There is thus no coercion and no conversion in this religion. It is believed that apart from humans and animal world even the vegetable world has life. This religion is all embracing and believes in plurality. No wonder Hindus include all shades of thinking, materialists (Chaarvaaks), atheists (Jains), agnostics (Buddhists), Shaivaites (worshipping Siva), Vaishnavaites (worshipping Vishnu and His incarnations), dualists, non-dualists and qualified monists, et al.

Batanya, an Apostle of Womanhood

by T.N. Dhar 'Kundan'

Whenever I hear the epithet ‘Batanya’ for a Kashmir Pandit lady two different pictures emerge on the canvas of my vision. I shall try to describe both but before I do, let me trace the origin of this word. In Sanskrit dramas the king is always addressed as ‘Bhatta’ and the queen as ‘Bhattini’, both meaning exalted and honoured ones. These two titles are used for Kashmiri Pandits and Kashmiri Pandit ladies in the modified form of ‘Bata’ and ‘Batanya’, respectively. These titles show the respect and reverence they have been commanding all these centuries not because of their wealth or riches, which in any case they did not possess in any substantial measure, but because of their scholarship, piety, character, wisdom and compassion and concern for every one.

The first picture of the ‘Batanya’ that I imagine is of an affectionate mother, ‘Bhawani’ of fair complexion wearing the traditional Kashmiri dress. She is wearing a coloured ‘Pheran’ with a snow-white ‘Potsh’ inside. The pheran is laced with a red border called ‘dur’ on the neckline and the bottom-line. It has a printed attachment on both the sleeves known as ‘Naervar’. She has a woolen muffler like belt round her waist. This is called ‘Loongya’, a corruption from Hindi ‘Loongi’. The headgear is a complex item. It comprises a cap on the head known as ‘Kalapush’ round which is tied a white folded cloth in four or five layers, called ‘Taranga’. Thereafter there is a plastic sheet either milky white, when it is called ‘Doda-lath’ or transparent like glass, when it is called ‘Sheeshi-lath’. Damsels, young in age would sometimes use a shining sheet with sparkles. This was known as ‘Zitni-lath’ – all the three names were true to their type and quality. On the back of this headgear there is a beautiful decorated covering of muslin called ‘Zoojya’ about one foot long tugged inside the cloth-folds. On the top of it is another white covering with a long twisted tail dangling down the back almost touching the heels. This is called ‘Poots’. When she goes out she puts on a cotton cloth, ‘Dupatta’ or a woolen cloth, ‘Voda Pallav’, depending on the weather, tastefully placed over the head and firmly held in front below the chin with the help of a black-headed pin called ‘Kaladar saetsan’. Incidentally the Malay women in Southeast Asia wear a similar headgear, which they call ‘Tudung’ not very different from Kashmiri ‘Taranga’.

A gold-chain in her neck, gold ornaments ‘Ath, Atahore and Dejhore’ dangling from both ears is a must for this gracious lady, a mark of her being married and a loving respected mother. On festive occasions and when attending marriages or feasts in relationship she adds some more gold ornaments to her beautiful get up. A necklace or ‘Honzur’ in the neck, earrings or ‘Kana dur’ in her ears, ‘Matshaband’, ‘Katshakar’, ‘Gunus’ on her wrists, ‘Talaraz’, ‘Chaphkael’, ‘Tolsi’, ‘Kantha-maal’ and umpteen different types of typically Kashmiri decorations adorn her personality.

This mother figure ‘Batanya’ gets up early in the morning. After the usual morning-chores and personal cleaning she cleans the front porch with stairs as also the three sides of the front door with a white clay paste. This is called ‘Brand-fash ta Dar livun’. Then she sweeps and cleans with the same paste the main gallery called ‘Vuz’ and the main stairs leading to the upper floors. Thereafter she goes to the Mohalla temple and performs pooja, does circumambulation and brings home some vermilion tilaka and holy water for other members of the family. On reaching home she sprinkles some water on all sides of the front door; this is considered auspicious. On her return journey from the temple, she sometimes purchases ‘Hak’ (Sanskrit – Shaka) also. On the riverbank and in the temple she prays for the welfare, longevity and peace and prosperity of every one. ‘Raja swasthi praja swasthi desha swasthi tathaivacha….’ Then she cleans the floor of the ‘Thokur Kuth’ and places a pot, filled with fresh water there for the elder male member of the family to perform the daily pooja.

Now she enters her theatre of activities, the kitchen. She lights fire in the traditional ‘daan’ with two or three cooking ranges. On one she cooks rice in a ‘Degchi’ and on the remaining two choicest dishes of ‘Hak’, ‘Monja’, ‘Nadaer’, ‘Oluv’, ‘Gogji’ and the like. While cooking, stirring the vessels and putting the firewood in order, she goes on chanting holy hymns like ‘Indrakhi Namsa Devi’ or a hymn from Panchastavi like ‘Maya Kunadalini kriya Madhumati’ or the favourite ‘Bhawani Sahasranam’ and I get the echo, ‘Madhur madhu pibanti, kantakan bhakshyanti’ and so on and so forth. These hymns, stotras and mantras sung in the accompaniment of these daily chores add taste and flavour to these dishes and the food. This ensures longevity, health and prosperity of the members of her family. In between she prepares ‘Mogael chai’, the typical Kashmiri black tea with cardamom, cinnamon, a couple of times and ‘Sheerye chai’, tea with milk, salt and common soda in the afternoon. After a brief siesta in the afternoon, when the men folk are away at work, she cleans rice, washes clothes, grinds wheat and pounds chillies.

Spare time is utilized in interacting with neighbours and keeping abreast with the happenings in the families living in the vicinity. She lends a helping hand where it is needed and gives her advice where it is sought. She is a source of encouragement and a key figure in ensuring moral make-up in those that are in distress or faced with some problem. Her words, ‘Narayan kari raetsrai – God will be kind and favorable’ lift many a depressed person. Come guest and she will not leave him unfed or un-served. ‘Ti banya, nyebokhui ma drakh – How can it be that you will leave without having something to eat’? In the true spirit of Vedic dictum, ‘Atithi Devo bhava – treat a guest like a god’, she serves every guest, known and unknown, with respect, love and care. Her philosophy is ‘Daan to’t ta bar vo’th – kitchen range always hot and ready to prepare food for the guest and the door wide open to welcome him’. If the guest is an elderly person she treats him or her like her father or mother. If he or she is of the same age as she, he gets the treatment of a brother or sister. If the guest is a youngster he is treated like a child with soothing love and a bundle of blessings. ‘Tse aay ta thadan paay – may you live long and ever prosper’ is the oft repeated blessing on her lips.

She puts up with the carefree nature of her husband and careless attitude of her children smilingly. She will put their personal effects, books, papers, clothes and other such items at their proper places. Sometimes she will scold the youngsters but these utterances will either mean nothing or be in the nature of good wishes. She will burst out, ‘Tse zeer gatshan’, ‘Tse paha lara phutani’, ‘Yi kyah sedyoy’, which amount to nothing as literally they mean ‘may you get a push’, ‘may your borrowed ribs break’ and ‘what has straightened in you’, respectively. On being wished and saluted she will shower basketful of blessings, to not only the person saluting but also to the entire world. To her own children she will wish, ‘Gatsh kulakyan gulan saan phol ta nav –May you blossom and prosper along with the children world over (literally, flowers)’. Sometimes she adopts another pious routine. She gets up early in the morning at wee hours and goes to Hari Parbat for circumambulation and offering prayers at ‘Devi-aangan’. Here also she prays for the welfare of the entire mankind, even for the plants and animals, skies and waters, ‘Sarve bhavantu sukhenah sarve santu niramaya sarve bhadrani pashyantu, ma kaschid dukhabhag bhavet – Let all be happy, let no one be worried, let every one be faced with good things and let no one be grief-stricken’.

This Bhawani- Maa is a pillar of strength. She has earthlike patience, ocean-like depth and sky-like vastness. She lends support and good counseling to the men-folk in the hour of crisis. She gives manners and imparts values, ethical and moral, to her children. She is at hand for relations, friends and neighbours to suggest solutions to their problems whenever they are faced with any, be it domestic, social or otherwise. She has advised many a daughter-in-law to try and adjust to the changed environment of her new home and try to endear herself to her in-laws. She has counseled many mothers-in-law to handle their new daughters-in-law with love, compassion and consideration and thus has contributed to the peace and harmony in their household. She is kind to the maid, the servant and the sweeper, who do all odd jobs for their family. She will feed them occasionally, serve them a hot cup of tea when it is cold and give them odd woolen items, clothing and other things of day to day use and thus subscribe to their comfort and fulfill their small needs.

Her compassion is exemplary. Whatever she cooks for the family a portion of it is earmarked for the birds. This she puts on the shelf outside in a corner of the window frame, called ‘Kaw paet’ or the shelf for the crow. A portion of the cooked rice she puts in two small brass pots called ‘Sanivaer’ and this eventually goes for the consumption of various insects when it is emptied every morning before being filled with fresh water. Before eating her food she keeps a portion outside her plate for the stray dog in the lane. This portion carefully shaped is rightly called ‘Hunya Myet’ or a portion for the dog. On Tuesdays, Saturdays and other holy days she prepares yellow rice with turmeric and distributes it among her neighbours. She shares everything brought by her daughter-in-law from her father’s house with her neighbours and relations. This includes walnuts on Shiva Ratri, yogurt on being in a family way, ‘Tsochi’ or pancakes whenever she comes back after a longer stay there and so on.

The second picture of the ‘Batanya’ that emerges on the horizon of my imagination is that of a daring and daunting ‘Lakshami’. She is beautiful and charming. She wears a sari with necessary paraphernalia of blouse, petticoat etc., a salwar-kameez or even a bell-bottom with top. She may or may not have the traditional Kashmiri ornaments like ‘Dejhor’ and ‘Atahor’ but she would certainly adorn a chain, a pair of ear rings, a couple of gold bangles and a ring. She is agile, quick and sharp. She may be dressed simply but she would be elegant and graceful. She would have don a little make up as well commensurate with the need of her environment as also social and official circle she moves in. Even in the attire common to the ladies of many other communities in our country, she would be conspicuous as a Kashmiri damsel because of her typically Kashmiri demeanour, mannerism and accent.

She is ‘Lakshmi’ and adds to the family income by her earnings. She may be a Doctor, a Lawyer, a Banker or an Officer. She could be a Teacher, an employee in some government or private office, a Media person, an Engineer, an Architect or in any other profession. She gets up early in the morning. After usual cleaning and a bath, she attends to her kitchen. In a short period at her disposal she has served bed tea to all, given breakfast to young and old, packed lunch boxes for office going males and school going children, prepared children for school and left a couple of dishes in the refrigerator for senior members of the family to consume at lunch time. If she owns a car she drives up to her workplace. Otherwise she rushes to catch a chartered bus and reaches in time at her desk. Whatever her profession she is well versed, efficient and an accomplished expert in her field. She is popular among her co-workers. She is respected by juniors, loved by seniors and held in high esteem because of her expertise and usefulness to the establishment and the organization. She is quick to grasp, fast in taking a decision and lucid and firm in expressing her views. Her compassion and consideration stands her in good stead here also. She is soft and well mannered and careful about her respect, prestige and dignity.

In the evening when she comes back from her work she again attends to household chores. Often she has to retire for the day late in the night. She looks after the needs of the elders, ensures that the children have done their homework, makes advance preparation for the following day and takes care of other household requirements. She not only adds to the family income and supplements the earnings of her husband but also manages the finances of the house efficiently. She does not like extravagance, wasteful expenditure and spending on un-necessary items. She saves money for the rainy day, for bigger social events and for more pressing and desirable items of expenditure. Her efficient management of the household and family earnings makes it possible that sufficient funds are available for the higher education and professional training of children. She foresees the requirements for their marriage and goes on making due preparations round the year. Her kitchen store, pantry, wardrobe and the storeroom are always full with various items of need. If the guests arrive, neat and nice bedding, sheets and towels are ready for him in the guest room. Her refrigerator and the freezer therein are always full with items that may be needed should an unexpected guest come and stay for the dinner. She is a perfect host and knows the relative importance of each guest. She entertains him as per the norms set by the family tradition and social custom.