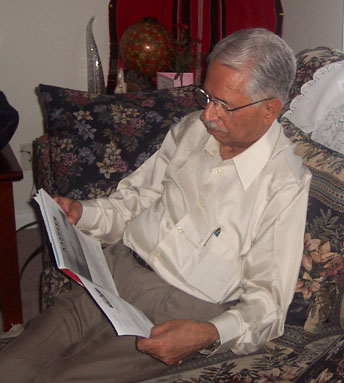

Dr. Harikrishna Kaul

Harikrishna Kaul is one of the major Kashmiri playwrights of the modern era. He started his literary career during his college days in early fifties, writing short stories in Hindi. He continued writing in Hindi till mid-sixties when he switched to writing in Kashmiri and immediately established himself as a major Kashmiri playwright and short story writer.

Harikrishna Kaul's plays are about ordinary people who provide us an opportunity to reflect on ordinary as well as larger issues of life and existence. The characters are real flesh and blood characters that one can easily relate to. The old man Lala Sahib of Yeli Watan Khur Chu Yevan is perhaps the best example of such characters created by Kaul. This widower and father of two middle aged sons painfully finds himself becoming increasingly irrelevant in the affairs of the family. His futile search for importance in the homes of his two sons ends up in his inability to decide where to go. He has nowhere to go. This character lives in the memory of all Kashmiris who heard the play on Radio or watched it on the television.

Another example of memorable characters created by Harikrishna Kaul is the old accountant of the humurous play Dastar. His uniquely archaic approach to office work became a legend and his famous lines Rama Lagay Chaanya Lilayecould be heard on the streets of Srinagar years after the play was first shown on television.

In mid seventies Kaul's play Natak Kariv Band was first staged at Srinagar's Tagore Hall. This play draws on the epic Ramayana and has Hanumana revolting against Rama's decision to banish Sita. As the play unfolds the audience finds Rama representing the ruling politicians who are ever ready to betray Sita, the people, for the sole aim of staying in power and Hanumana unmasks this betrayal crying Natak Kariv Band. This play is a milestone in Kashmiri literature and has been staged in Hindi as well as other Indian languages. The chief minister of the state, Shiekh Abdullah saw a performance in Delhi and was deeply moved.

Harikrishna Kaul's characters like the ones mentioned above are still popular in a Kashmir that is fast loosing its touch with a secular past.

The exodus of the Kashmiri Pandits from Kashmir valley in late eighties has robbed Kaul and indeed all other Kashmiri Pandit playwrights the platform on which they presented their plays. There are no audiences or listeners or viewers. So his literary contibution is now mostly in the genre of short stories and novels. He has won many national awards for his writings, including theSahitya Academy Award, but has lost his audience.

Short Stories

Sunshine

Harikrishna Kaul

Contemporary Kashmiri Short Stories

Arriving in Delhi, Poshikuj found herself in a totally new world. She heaved a deep, contented sigh. The best part was that there was no Muslim in sight - everywhere her own Pandit brethren. The vegetable seller a Pandit, the barber a Pundit, the milkman a Pandit. Above everything else, there was deliverance from that fishwife! The 'fishwife' meaning her elder daughter-in-law, the very thought of whom gave her goose pimples. How she would pounce on her like a witch at the slightest excuse! There was a time when no one had dared to take her name in vain, but thanks to that virago, her name had been dragged in mud. Well, God had also 'rewarded' her as she deserved. Otherwise, born of the same mother, why should the destinies of Gasha and Saaba have been so different? Look how Saaba is prospering here, and Gasha? Not enough to eat even. And all because of that fishwife's deserving. No, she would not go back to Kashmir even when summer came, she was resolved.

It was around ten in the morning when Poshikuj came into the courtyard to sit in the sun. Half the courtyard was paved in brick and the other half was turf. Around the turf were flower-beds. Potted plants decked the paved part and flowering creepers hung from the roof of the house. Saaba was the pet name of Poshikuj's younger son Surendranath, who had been allotted a nice 'D-II' type Government house in Sarojini Nagar. On the ground floor were the drawing room, bed-room and kitchen. An open space in front of the kitchen had been converted into a dining room with a table and chairs. A toilet, bathroom and two bedrooms were on the first floor. There was a terrace and a Barsati on top.

Surendranath had gone to England on scholarship for higher studies, and it was there that he had found a job in the Indian High Commission. He had been transferred to Delhi three years back, posted to the Ministry of External Affairs on a post of some importance, earning around a thousand rupees per month. He had been married before going to England, which was a matter of some regret to Poshikuj. Had he been unmarried before going abroad and landing this plum Job, what a catch he would have been! The richest and the noblest of the land would have been begging before Poshkuj now! But what was written down in fate could not be undone, so she never let anyone suspect this secret sorrow of hers.

Poshikuj sunned herself to her heart's content in the lawn, feeling the warmth seep into the sinews of her neck and back, relaxing them. It seemed that her rheumatism from Kashmir was all gone. She looked up to the sky. Its glassy blue pleased her very much. On the upper balcony she could see the washing that Chhoti had hung out to dry. How they shone in the bright sun! The foreign machine was certainly a boon. Chhoti could not have taken more than five minutes to finish the washing and yet how sparklingly clean the clothes looked! Suddenly her train of thought was disrupted when she happened to see Chhoti's undergarments among the washing. And she blushed with embarrassment. Oh God, what must the neighbours think of such immodesty? She got up and began to pace the courtyard. On an impulse she went and plucked some flowers, gathering them in the 'palloo' of her sari. She would take Chhoti along and go to a temple, perhaps the Birla Mandir. They say it was a worthwhile sight to see. It would not take them too long, half an hour at the most. They would be back before lunch. She went in, put the flowers from her sari 'palloo' on the dining table and sat in a chair, waiting for Chhoti to come downstairs. How long she takes! Must have been in the bathroom for more than an hour now. God only knows what all she rubs on that body of hers. Coming to Delhi has certainly changed her, all restraint and propriety forgotten. But still, you had to admit, she is a thousand times better than that fishwife!

After a while, she heard the bathroom door open and Chhoti came clattering down the stairs. She wore fresh clothes - a crisp sari and a matching blouse. Her hair was not done yet, but still she looked better now, not floating around in a gown as she was earlier, thought Poshikuj.

"Oh no, Mataji! What have you done?", the sight of the flowers on the table drew a cry from Chhoti. Poshikuj was stunned - she knew she had done something she shouldn't have.

"Why did you pluck these flowers from the garden? Particularly these hollyhocks?", there was a tinge of anger in Chhoti's sense of loss.

Her daughter-in-law's sharp rebuke hurt like death. And all for just a few flowers! How the woman preens herself on her new sophistication. There I was just 'Kakni' and here she has elevated me into 'Mataji! Mataji Shit! But swallowing her fury, she said in a low voice, "I thought we could go to the temple."

"You should have told me first. There is no temple in this location, nor anywhere near. The places close are the Ashoka Hotel and Chanakyapuri."

"What is that?"

"Oh you wouldn't understand. Come, let us go and sit in the sun." Poshikuj was stung - she seemed to be on fire from top to toe. This daughter of the notoriously stupid Govinda understands, and I wouldn't? The cheek! She needs to be put in her place. Asking for it, she is, otherwise she will walk all over me. No, I must assert myself.

"Do you take me for a complete fool? Don't I know about the Birla temple here, where people throng from all over the place?"

"Birla Temple is very far away from here. Farther even than Connaught Place and Gole Market, it is."

Poshikuj did not believe her. It was only the other day when she had seen something like a temple in the distant western horizon where the sun sets. It had blue domes. She was sure in her heart that this must be the famous Birla Temple. She fumed to her daughter-in-law with a determined look and said, "Then what temple is it that can be seen from the terrace? The one with those blue domes? The cleaning woman also told me that that was the Birla Temple."

"What does the cleaning woman know, Mataji? That building is neither a temple nor a mosque, it is the Pakistani Embassy - Pakistani office, as they say."

Poshikuj was revolted at this explanation from her daughter-in-law. What a fool this woman takes me for! The brazen lie! No one dares to openly mention the word "Pakistan" in Kashmir, even though there are only Muslims around. And she would have me believe that there is a Pakistani office in Delhi, where there are only Pandits everywhere? What a cock and bull story this daughter-in-law of mine is cooking up! But who can argue with a shameless liar? Poshikuj restrained herself, not wanting to get into a fracas with this one and have another scene like the ones with that fishwife. She had no strength to deal with viragoes-silence was golden at such an occasion, she told herself.

It was around twelves Chhoti lit the gas and made rotis. Then she warmed the vegetables which had already been done in the pressure cooker in the morning. She laid the table and placed two tumblers of water on it. She sliced some onions in a plate and squeezed a lemon from the fridge on them. Poshikuj saw the preparations for the meal and said, "Don't set a place for me on the table, I am not having your 'lunch'."

"But why? Do you want to fast?"

"Why should I fast? Let the plates be. Give me my roti in the small basin and I'll have it here, on the floor", saying this, she went up to her room and brought down the rag of a curry her bedding from Kashmir had come wrapped in. She spread it on the floor. Chhoti merely looked at her and brought had a dozen rotis in a small basin, the vegetables in a small bowl. Poshikuj took out a small towel from her petticoat pocket, spread it out and laid the bowl on it. The basin she held in her lap and began to eat with relish.

The meal over, Chhoti went up to her room. She came down after about an hour, dressed up and hair done smartly. "I am going to Miss Kapoor's. I shall be back by three o'clock", she said.

Poshlku, did not reply, but her silence made no impact on Chhoti. She merely looked at her watch and left. Poshikuj felt rebuffed. But she told herself not to mind, who was she to stop her? Let her do what she will.

She went back to the garden. The warmth of the sun soothed her ruffled feelings. One could give anything for this lovely winter sunshine! To tell the truth, this was the only worthwhile thing here, she thought. She pulled her sari up and began to scratch her leg. Her eye fell on her feet and she saw the chapped skin and cracked heels. God damn the winter there! How it ruins one's hands and feet! And then she thought of Bittu and groaned. The poor wretch! His chilblains had turned into suppurating sores. How many times I warned that witch to take better care of her son - make him wear warm socks and fur shoes, I used to tell her a hundred times. But would she ever listen? But then, a fur shoe does cost a pretty penny. And what is poor Gasha's salary, after all? Barely enough to make two ends meet. Come to think of it, he doesn't have an overcoat to wear. How he must shiver in the cold outside! It is all a matter of luck, nothing else. She heaved a sigh.

Poshikuj looked around at the flats. All was silence. No one in sight, as if everybody was dead. Aren't neighbours supposed to interact with one another all the time? But here they might as well be living in different countries, completely oblivious of one another! But even if they did mix, how would she understand their foreign gibberish? Besides, the names of these women are equally strange: one is 'Mrs Jain, another 'Mrs Sunder,' a third calls herself, 'Mrs Prakash' and still another is Mrs Something! Just look at this Sikh woman next door. Her daughter-in-law must be my age but still she is called 'Mrs Khem Singh' - God knows what this 'Mrs' means? Well, this city may have something to it, but frankly, what does it have?

She heard the rumble of a scooter, and knew Saaba was back. He came in and asked her, " How was your day, Ma ? You O.K?"

"I am all right, son, May God shower prosperity on you."

Saaba went up to his room but came back immediately. "Where is she?" he asked Poshikuj.

"She said she was going to see Mrs. Kapoor!"

"Which Mrs. Kapoor?"

"The same who does all those things to her hair, I mean the one who is rather fair and slim."

"You mean Miss Kapoor."

"That is what I said."

Saaba burst into laughter, "You never said that. It is Miss Kapoor, meaning Kapoor Sahib's daughter. You called her Mrs. Kapoor, which would make her his wife!"

"Let her go to hell for all I care! How should I know these subtleties ?"

"You will have to learn these subtleties now that you are staying here," Saaba turned to go up but Poshikuj stopped him with, "How come Chhoti is so close to this Kapoor woman? I do not quite approve of her ways, let me tell you."

"Oh come on, she is all right. How does it matter? We have to watch our own interest, that is all."

"What is that supposed to mean?"

"It means that her father is a big officer in All India Radio and that Chhoti is trying for a Job there."

"What do you mean? Do you want your wife also to work now? Is not your big salary large enough?"

"It is not a question of money alone. She gets so bored here, it would be a good change for her. And then, if your income increases, is there any harm in it? There are so many needs and expenses, you know. We have a radio, yet no T.V. We have a scooter, but no car."

"You are just being greedy."

Saaba merely laughed. His glance fell on the curry and he asked, "Who spread this rag on the floor?"

Poshikuj could feel that Saaba was angry. Softy she said, "I did."

"Why?"

"I find it difficult to eat, seated in a chair at the table, son."

Saaba said nothing. Soon after, Chhoti returned and he took her aside and the two had a brief consultation with each other. After that they had tea. Then they called a cab and taking Poshikuj along, went to Chandni Chowk. Here they bought a steel thali, a wooden Chowki and a pair of chappals, a voile 'Chikan' sari and a small Shiva idol for her. Once home they served her food in the steel 'thali'.

That night Poshikuj could not sleep at all. All kinds of thoughts kept coming in her mind, leaving her restless. So they are thinking of buying a car. What luck for this daughter of Govinda the idiot ! Well, you had to say that she has brought luck to our family. On the other hand, there is that wretched one, bringing nothing but misfortune to home and hearth! God knows whether Gasha bought a bicycle or not? He was saying that if available on instalments, he would certainly get one. The poor fellow has worn his feet out, trudging from Rainawari to his office every day.

Come to think of it, a quilt is too heavy for the weather here. God knows how cold it must be there. I will ask Saaba to write to Gasha - he must not stay too late. To hell with that Jawahar Nagar tuition work, God forbid if anything should happen to him, we won't be worth a penny. ----

Just think of all that abundance of things available at Chandni Chowk! How many clothes! Such perfect outfits for Bittu. If I had been carrying my own money, I could have bought something for him. Well, if I ever go again I will definitely get a shirt and shorts for Bittu - and a hockey ball. I must also get bangles for the girls next door. And that fishwife must also have a sari or something. Of course, if God should spare me, Saaba will keep me in luxury. He was telling me that he would take me to Hardwar next month. How keen that departed one was to go to Hardwar! But even after death, he could only reach Shadipur. How could poor Gasha afford those five, six hundred rupees for the journey all the way to Hardwar? Had Saaba been here, things would have been different.

So there are Muslims here too! All those burqa-walis in Chandni Chowk. Would they also be feeling the same fear here that is always there?

She heard the door of Saaba's room open and someone walked on the cement floor with rapid steps, Poshikuj recognized the footsteps. After a while there was the sound of the bathroom flush. Curse the woman's bowels, Poshikuj commented to herself, but what could you expect, after consuming gallons of that dal with rice in the evening? The roar of the flush must have woken up the whole neighbourhood. Why, she should have had it broadcast from the radio! Isn't that the place where she is supposed to be working now?

As the dawn broke, Poshikuj left her bed, went to the toilet, had a bath, and came back to her room. Wrapping a blanket around herself, seating the Shiva idol in front, she began to chant a bhajan. She knew bits of the Shiva Mahima Stotra and recited them too. Her prayers over, she went up to the terrace and sat in the sun. The sky here seemed much wider, it was not like the bounded sky of Kashmir, mountains all around and a tiny patch of sky in the middle. Perhaps it was due to this unbounded expanse of sky that people's vision also widened here, material prosperity must uncloud mulds too. One loves to have baths here, so easy to keep oneself clean and tidy. Her thoughts were interrupted by Saaba's call, and she came down. The table was set with cups and saucers, bread and eggs. Saaba, was wearing dressing gown, reading the newspaper. Chhoti came in from the kitchen carrying a tea-pot. She was in a gown-like garment, her hair tied with something that looked like a strip of red cloth. Placing the tea-pot on the table, she went to the fridge and brought out butter and strawberry jam, both of which she proceeded to apply to the bread. Poshikuj ate a couple of slices of bread with her tea. She other two had eggs too. Watching them, particularly Chhoti, eating the eggs made Poshikuj think of Bittu. How thin the poor thing was, yet not even a cup of milk was available for him. If that, mother of his had allowed him to come with me, his health would certainly have improved in this winter sunshine.

The tea over, Saaba went to his room. Dumping the cups and plates in the slim for the 'Lila' to wash, Chhoti followed. After some time both reappeared, spruced up, smartly dressed. Poshikuj gave them an appraising look.

"I am leaving for office Ma, and she will come with me up to the market. I will help her buy the meat", said Saaba and pushed the scooter outside. He sat on it, with Chhoti on the pillion. She put her right hand on his shoulder. Phut, Phut, Phut went the scooter, speeding on the road.

Would Gasha have purchased the bicycle after all? I could have given him the fifty-sixty rupees I have, to help him out. I could send them to him. Poshikuj was lost in these thoughts when suddenly Miss Kapoor materialized before her. After saying namaskar she asked in Hindi. "Mrs. Bhan is at home?" Poshikuj understood the question and replied in her broken Hindi, "market - get meat".

Miss Kapoor smiled. Poshikuj did not like her smile. Indifferently, she said, "Sit - she come soon". But Miss Kapoor did not sit with her, she went into the drawing room instead, sat on a sofa as if she owned the place.

"What does the bitch want here?", Poshikuj said to herself and shrugging for shoulders went to the lawn to sit in the sun. Chhoti returned with her shopping and Poshikuj told her, "There is someone waiting for you inside. Mrs. Kapoor, it is."

"Mataji, not Mrs. Kapoor, it is Miss Kapoor."

"All right, Miss Kapoor let it be! One speaks to her normally and she laughs at one in return!"

"You must have misunderstood. The poor thing is not that sort", saying this, she too went into the drawing room.

Her daughter-in-law did not believe her. This hurt Poshikuj deeply. But it was her own fault, intervening without rhyme or reason. The couple think no end of the bitch. No wonder they do, considering they need a favour from her father. Miss Kapoor, indeed! God knows how many men she must be intimate with, and she is still a Miss, Poshikuj snorted to herself.

Warmed by the sun, Poshikuj had began to doze when a burst of laughter from the drawing room made her sit up. They were laughing at her, she knew. The mortification was worse than death.

She would not stay here long. She must soon find someone to go back to Kashmir with. She could leave within the next few days in that case. And if she could, the only thing she would carry back with her, would be heaps of this winter sunshine!

The Saint and the Witch

Harikrishna Kaul

Translated from Kashmiri by Neerja Mattoo

Tarachand died at five-thirty in the morning. The news reached Ramjoo's residence at seven. Immediately after, Ramjoo, Sonamal and Heebatani left Jawaharnagar for Bana Mohalla.

"Salutations to such a death!" said Ramjoo. "No pain, no illness. It was only the other day that I met him at Habbakadal. And we stood there a long time, talking of this and that. Do you know what he said to me that day? 'Let the weather hold a little, I'll come and spend a few days with you all at Jawaharnagar.' Ramjoo heaved a deep sigh and added, "only goes to show you - how near death is!"

"A fine release for him, nothing but snubs and knocks for the poor woman left behind", Sonamal said, "even the ones born from your own womb do not bother these days, what can you expect from an adopted son? Dear God, let me not live a day without my husband - let me go into Your arms with all the marks of my marriage intact!", she wiped a tear with a corner of the long veil covering her head.

"Poor fellow, such a saintly soul he was! So obliging - always ready to help, be it friend or stranger. So good to everyone! And then he weilded such influence too - seemed to know everyone who mattered, and they held him in such high esteem", Ramjoo elaborated.

"He looked like Lord Indra himself", Sonamal gushed, "his parrot-green turban, almond-coloured shervani, tight-fitting white trousers and feet shod in fine moccasins - how well they suited him! I have never seen his footwear unpolished."

"Well, he was certainly a 'gay cavalier' in his time," Ramjoo chuckled, "don't you remember the stylish angle his turban had? When Gasha was getting married, I - as the husband of his eldest aunt - was the one who had tied the bridegroom's turban. But the wretch had it untied and declared that he would not step out for the bride's place unless his turban was tied by Tarachand!"

"They say that even at this age he would walk up to Hari Parbat every morning," Sonamal touched upon another aspect.

"Not only that - he would spend every Saturday night at the feet of the goddess Chakreshwari; every Ashtami would find him before the Devi at Khir Bhavani."

"What a voice he had! One day I heard him singing bhajans at Khir Bhavani - it was just like so many bells ringing at once."

"He was a Raj Yogi, in fact. While seeming to enjoy all the luxuries of this life, he had attained a spiritual plane too high to comprehend by us. Who knows what secret mantras he chanted?"

"That is exactly what stood by him at the end. They say that all great souls relinquish their bodies in this very manner: one minute they are there and the next, gone!"

"Didn't I say that one should salute such a manner of dying?"

Heebatani heard her brother and sister-in-law's comments in silence. Their words seemed to torment her. She wondered why they could not observe even a minute's silence. How could they be rushing off to Bana Mohalla with such enthusiasm? One would think they were going to a party. Did they not feel even a shred of sorrow at this sudden death - Tarachand's death? She herself was devastated, numbed with grief. Had she had even the least suspicion that Tarachand would be gone so soon, would she not have rushed to him, touched his feet and sought his forgiveness? Would she not have fallen at his feet and confessed that truly it was she - she alone - who was guilty of harbouring the sinful thought at that fateful time when she had almost destroyed a life-time's achievements of a Tapasvi, a rishi like him. She was a sinner, she would have said, and asked for absolution from him. But alas, he had not even given her the opportunity for such penance; Tarachand's death had dealt her a blow the anguish of which would stay with her till death.

"There's no denying that Tarachand was a saint," Ramjoo continued to eulogize the departed soul.

"A saint indeed! A god, I would say," Sonamal corroborated heartily.

"Pure heart, pure eye and handsome like a god - that was Tarachand. And his wife? Ugly as sin. Yet he doted on her, ready even to hold out his palms to receive her spittle!"

"How right you are! A woman like Tarawati? What an absurd match for a man like him. The like of her does not deserve to be called a wife. No looks, no brains, no grace of any kind. Just a lump of flesh trailed by a veil."

"That may be so, but you can't deny that she is the real victim of this blow. Who can tell how Natha will treat her now, whether she will have any comfort from him?"

"What comfort did she ever give him? As she has sown, so shall she reap."

"What can you expect from such a relationship? It is always the same in such cases: the mother never contented with the adopted child and the child equally disgruntled."

"How can you say that?" Sonamal countered, "Nathji is a real gem. And his wife Shanta - meek as meek can be. The two of them would not allow Tarawati to lift a finger for any work. More likely than not, it is your own offspring who is ready to pluck out your entrails these days" Sonamal tied the sash round her pheran a little more tightly.

"But Tarawati has raised Natha as her own from his infancy."

"As if I know nothing!" Sonamal contradicted her husband, "I did not always live in a bungalow at Jawaharnagar (bless my Saiba for it!). Wasn't I their tenant for all those years? I know every bit of the goings on in that household. Not once have I seen her brow free from a frown - always a sour face, that one. Well, God also treated her the way she deserved. Better be a bitch than barren, that's what I think."

"How does it matter now? Our relationship was all with Tarachand - he is in heaven and the story ends."

"Yes, it was only he who knew how to maintain relations, the courtesies and graces of hospitality," Sonamal had still not exhausted herself talking. She continued, "As for her - the very sight of a guest would send her into mourning - as if her father had just died!"

"Tarachand enjoyed life to the full, not only enjoyed all the luxuries for himself, but ensured that others had them too. Actually he was in government service at a time when it meant something to be in it. Wherever he was posted, he received royal treatment. He did not have to suffer the indignities of this 'People's Raj' too long either - he retired soon after it was imposed on us."

"Oh yes, he certainly did relish all the pleasures of this world. This must have been his only sorrow."

"To tell the truth, Tarawati is not so bad, only she is rather dumpy."

"I did not mean her looks alone every woman cannot have the beauty of a part, but this one seems to be a case apart. Knowing full well that her husband was a man of refined taste, delicate feelings, a lover of cleanliness, tidiness and neatness, she should have paid some attention to her own grooming at least. But she seemed to find even washing her face a chore. Dressed in a rag of a pheran, there she would sit at a window, mourning God knows what. Her hair always tangled, the tresses lank with grime, she looked like a witch indeed - God save us from Evil!"

"But Tarachand never complained at all," Ramjoo said.

"Never!" Sonamal agreed, "he looked after her so well. You won't find such devotion even among the most modern of husbands."

"He was certainly a god incarnate, but his life was wasted and ruined by this witch."

Tarachand's life had been wasted and ruined - the realization of this had dawned upon Heebatani before everyone else; perhaps because her own life had also been wasted and ruined. She had just completed fifteen years of age when she was married. Within five years she found herself a widow. But even out of those, more than three must have been spent in her parents' home.

All that was a thirty year old story. Today Heebatani could not even remember the face of the partner of that brief companionship. With the greatest effort, she could only stir a dim recollection of a vague form: an eighteen or nineteen year old Kashmiri Pandit youth, thinly built, shy. When she used to go up to the store-room to bring down rice or spices, he would follow, stalking her. But the loud shout of, "Damodaraah!", from his mother's powerful lungs would send him scurrying like a dog with docked ears into the small room next door. How stern, how formidable his mother was! Far from giving the couple the privacy of a room of their own, she did not even allow them to exchange a few words with each other. The moment Heebatani returned from a long visit to her parents' house, her husband would find himself despatched to his maternal grandparents' place - so apprehensive was the mother of losing her grip on her son. But in spite of all her efforts, lose him she did in the very fifth year of his marriage, for ever. The mother herself did not survive the son more than a year. For a long time after, Heebatani could see nothing but desolation wherever she turned. After her mother-in-law's death, her brother brought her home. For about a year she was looked after very well, but soon her sister-in-law put her to work, scrubbing and washing in the kitchen. Heebatani thought that this was what she had been made for. Accepting the finality of her fate, she plunged wholeheartedly into the drudgery and chores of her brother's house- hold. Soon after, Ramjoo's relations with his collaterals soured, and as a result of the family dispute, he moved out and became a tenant in a portion of Tarachand's house. You could say, without fear of any contradiction that it was here that a new life was breathed into Heebatani, thanks to Tarachand. He gave up going out in the evenings after returning from work, taking up the task of imparting religious education to Heebatani instead. He would read out the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Bhagwat and Shiva Purana to her. He bought her copies of the Bhagwadgita and Hanuman Chalisa to study. Instead of sweeping and mopping the floors in the mornings, Heebatani now went to the temple, gently pouring water on a Shiva Linga. She also began to follow Tarachand's practice of observing the Ashtami, Amavas and Purnima* as days of fasting and prayer. On these holy days, she would cook the ritual food - rice and vegetables - for Tarachand herself, simmering the sweetened milk till thickened, frying pakoras and potato chips and making halwa and sago kheer according to strictly laid down religious prescription. After he had been served and fed, she too would eat the same food. Tarawati could not have been too happy with Heebatani taking over these duties from her, but she could not say anything.

Heebatani went on pilgrimages to several holy places with Tarachand. On a number of Ashtamis, she went to Khir Bhavani with him. It was Tarachand who was responsible for her going to Bhavan in Mattan where at long last, she had the shraddha of the poor dead Damodar performed. Once when news came that a Sadhu of great spiritual power had taken up residence in Chandigam, Tarachand took her along to seek his blessings. They stayed at the Sadhu Babaji's ashram for a night. The next afternoon they left for Sogam on their way home.

The memory of that fateful day sent shivers down Heebatani's spine even now. On the way, it had started to rain - a sudden deluge that seemed to crush stones into sand with its fierce power. Drenched to the bones, their clothes dripped wet as though they had both had a dunking in the river. And to top it all, there was no bus for the town at Sogam. Luckily Tarachand found an acquaintance in the overseer of the area. The overseer himself was away in Srinagar, but Tarachand had the chowkidar open his official residence for them. The chowkidar lit the iron stove and hugging its warmth, they dried their wet clothes. At about five, Tarachand went out and bought some meat and asked the chowkidar for some rice, oil and spices. Heebatani went into the kitchen and cooked a meal. After they had eaten, she spread the overseer's bedding for Tarachand. For herself, she took a couple of blankets and lay down. But sleep eluded her. There was not a moment's lull in the rain. The month of July had become as bitingly cold as December. She tossed and turned on the cold floor for a long time, unable to find restful sleep. And then she quietly slipped under Tarachand's quilt. As her arm fell across his back, he woke up. Finding Heebatani in his bed, he leapt out, went to the pitcher of water, washed his hands and feet and sat down in the classic asana for meditation. Heebatani ran into the kitchen. In that refuge, she dug her teeth into her flesh. How she wished that the earth would open up and she jump into the abyss and disappear for ever. Her eyes turned into crumpled, dried apricots with incessant weeping. For a long time afterwards she could not meet Tarachand's eye. It was God's grace that soon after, they shifted to Jawaharnagar permanently. As they were leaving, there was a bitter altercation with Tarawati for some trifling reason, with the result that interaction between the two families ceased for the next few years.

A long time had passed since then. Heebatani was almost fifty now. Many a time the thought had occurred to her that she should go to Tarachand and seek his forgiveness for her sin. But perhaps the shame was too deep for her to face him - something always prevented her from carrying the thought out.

The road from Jawaharnagar to Bana Mohalla seemed too long even now. She was in mortal fear that they might have taken him away before their arrival.

It was eight by the time they reached Bana Mohalla. Tarachand's body was still there. A flower-bedecked plank had been prepared, and it lay waiting in the yard. There was a large gathering of people sitting on mats around, everyone of them relating the good deeds of the departed. Ramjoo sat down among them, Sonamal and Heebatani went in. Seeing them, Tarawati and a few other women set up a loud wail. Sonamal went close to Tarawati and pressing a handkerchief to her lips, stopped her from crying. Heebatani did not go near Tarawati. She went up to where Tarachand had been laid down on a bed of grass. Taking hold of the dead man's feet she wept profusely, emitting loud cries of, "Oh my father, brother, guru!"

After a while she rose, prostrated herself before Tarachand's body and said, under her breath, 'It is true that I was the one enfolded by darkness. Please forgive me my sin. This life of mine was a complete waste and ruin, let not the same happen to my next one. I must have your forgiveness.'

Tarachand's body, laid on the plank, was carried away at about eleven, elaborately decorated with wreaths and garlands of fresh flowers. Just before the pall-bearers lifted the plank, an expensive shawl was spread on it. Tarawati followed the funeral procession into the alley, weeping and wailing loudly. She was brought back, a couple of women supporting her. Once inside, she sat quietly for a long time, stunned into silence. Then, all of a sudden, she burst out to the women gathered before her, "Forgive me, my sisters - for fifty years the seal on my lips has not been broken, but now that he has left the house, I must speak. Look at me, even now I am that seven year old, untouched, unravished child bride!"

Heebatani seemed to fall from a great height. It was as though a light had begun to shine upon many a dark corner, an answer given to many an old puzzle. She rose and took the other woman in her arms, and the two women howled together.

The eighth day of the lunar fortnight, the night of the new moon and the full moon night respectively.

The Mourners

Harikrishna Kaul

Tarzan's sister-in-law sat before the chulha. She was out of breath with the effort of blowing into the damp firewood and cow-dung cakes, but they refused to kindle. The small kitchen was filled with smoke. Dakter asked her, "Where is he? Dead as a log as usual?"

The smoke from the wet firewood stung her eyes and the sight of Dakter standing before her infuriated her further. She wanted to pick up a smouldering stick from the chulha and with it, break every bone in his and his friend's body. On this bitterly cold morning why had he come to tempt her brother-in-law to go God knows where? But then she thought, why blame him - it was the fault of your own hen if she went to lay her eggs in somebody else's yard. He read the meaning in her silence and saying, "Still sleeping, no doubt," started going up the stairs. He could hear her grumbling, but being in a hurry, he did not stop to give her a piece of his mind.

"Get up you rogue. Pedro is finished," he declared as soon as he entered the room. Curled up like a bundle on the bed, Tarzan sat up at the news. He could not quite comprehend the meaning but knew that something was wrong. "Fellow's mother is dead," Dakter said, sitting down near the pillow. Tarzan stretched his arm to push the window open. An old blanket, torn in many places, was spread over the quilt and over it, his woollen pheran. The pillow was red chintz but without a cover and had been absorbing the grease from his hair for no one knew how long. On his right hand side lay a number of cut-outs of movie queens from film magazines and tabloids. On his left was a cigarette pack containing a half-smoked cold stub and two whole cigarettes.

"When?" he asked.

"Early morning today, they say." Dakter took out a cigarette from the packet and lit it from the embers in his kangri. "But I think the old woman must have kicked the bucket sometime during the night itself and the fellow would not have come to know till the morning. The rogue was on his own trip."

"How mean of him - on a trip without us!"

"I didn't know of it either. But I heard that there was a big do at Patwari's place. If I give you the guest list the earth will shake under your feet."

"Then the rascal is sunk. Which wretched fellow led him to that den? Five-rupee notes rich as it were, on the cards there day and night. Pass me a cigarette, will you?" Dakter gave him the other cigarette from the pack.

"Give me the kangri too." He handed it to him.

Tarzan lit the cigarette from the embers and drew the kangri under his quilt. "Now the rascal can live it up. His mother was the last check and she too has sailed off. Now he may as well sell his house and blow it up on cards ... who is to stop him?"

"Take my word for it-the house will go."

"Yes, but what do we do now?"

"Which son-in-law is there to take the old woman to the cremation ground? Get up and gird your loins."

"My loins are already girded. Come on, bring all the mothers and fathers who need my shoulders to cart them to their cremation."

Tarzan left the bed, put on his pheran, wore a thick balaclava on his head to cover his ears, pulled out three pairs of socks from under the pillow and put them on. Handing the kangri to Dakter, he said, "Let's go, I'm ready."

"Hold on, will you. Let's finish the fag at least."

"Okay. Carry on. The old woman did not show any hurry while alive, why should she be in a hurry now?"

Tarzan picked up a kangri from the ledge and gave it a thorough shaking so that the ashes settled down at the bottom and the charcoal nuggets were thrown up. He asked Dakter for a live coal, put it among the nuggets in his kangri and, blowing upon it furiously, kindled a warm blaze.

"Won't you fill fresh charcoal in your kangri?"

"Forget it. It's better to ask the baker in the street to give me some from his oven. Why provoke taunts on the matter of a kangri-full of live coals early in the moming? What's the score?"

"Who cares."

"If they can take six wickcts in today's play, they might win."

"Like hell they will," Dakter made a gesture with his thumb, "As if this is the only match left for them to win! As if they have triumphed in all the others!"

They had walked out of the room when Dakter went back and returned with the half-smoked stub stuck behind his ear, "Why leave it?" he said to Tarzan.

Slowly they descended the stairs. Tarzan's sister-in-law stood watching them from her doorway. As they were leaving, she mumbled in her mixed Punjabi-Kashmiri, "What does he care? No sooner does the day dawn than he must saunter forth-a babu, no less, with his scents and oils! Stuffs his belly with mounds of rice but does he care where it comes from? Only I know or my fate knows!"

"Hey, when did your brother acquire this Punjabi pigeon?" Dakter asked Tarzan as they walked away.

"Come on, at least he's got a pigeon, whatever sort. As for us, we shall not get even this".

"Talk about yourself. As for me, I have a love affair going!"

Tarzan looked him up and down and burst into laughter.

In the street, Tarzan had his kangri filled with hot, glowing mulberry charcoals from the baker's, picked up three packs of cigarettes from the grocer on credit and, pushing them down his Pheran pocket, said, "Now I am equipped to take the whole bloody town to its cremation-absolutely at your service!"

"Didn't you ask the baker the score?"

"His transistor batteries are exhausted." He took two cigarettes from the pack, gave one to Dakter and lit one for Himself. Dakter threw away the half-smoked stub.

"I had thought I would spend the whole day listening to the commentary. How could I expect this nuisance to turn up? Today of all days! Tell me, how soon can we be free?"

"One o'clock - maybe two."

"Shall we listen to the commentary or . . . " Tarzan remembered something and did not complete the sentence. Instead he asked, "Shall we go to this one?"

"Stupid!"

"The other one?"

"The same old headache."

"To this side of the river?"

"Who knows! It was released only yesterday."

"The other side?"

"Heard it's good."

"If we are free by one o'clock, we will go to see it, otherwise the commentary."

"I'll not sit in the third class this time."

Tarzan stared at him for a while and said, "Since when have you acquired a taste for balcony seats to watch a film?"

When Pedro realised that his mother had turned to clay, he did not weep or cry. He just went quietly to Pahelwan's house, who first informed Seth and then went to fetch the Brahmin priest. On the way he met Dakter's younger brother through whom he sent word to Dakter. Seth stuffed fifty-sixty rupees in his pocket and went to the store which stocked all the stuff needed for the rites at a Hindu funeral. It was only after all this had been done that Pedro started to wail loudly, calling out his dead mother's name. This brought a few neighbours, who formed a small gathering in the house.

Pedro had no relatives in town other than a cousin's husband from his mother's side. And he too lived at a distance of five or six miles. Pedro did not send a message to him. Even if he had, he would not have turned up, Pedro was certain. In fact, Pedro hated all his relatives, whether they lived in the town or the village. It was only his mother who had served as a bond between him and his relatives. Today that bond too was broken with her death. Now he was free - free in every way. He did not have to salute or bow before his relatives. He did not have to perform the ritual shraddha for his father every year. He did not need to return home every night. He could do exactly what he wanted. From now on he could be his own master-the master of his own house too.

Pahelwan arrived with the priest an hour later. One woman from the neighbourhood began to warm the water to give the corpse the ritual bath. Another swept a corner of the yard and smeared it with cow-dung paste to purify it for the performance of the last rites. The priest began. Pedro was shifting his sacred thread from the left to the right shoulder and back again according to the priest's instructions, when Dakter and Tarzan arrived. Tarzan went directly to Pedro and whispered in his ear, "Got any money?"

"Yes, yes I have."

"Swear upon this very mother?"

"I swear upon my mother. I do have money."

"That's all right then." He went and took his seat on an upturned mortar in a corner of the yard. When the corpse was being bathed, he got up and said to Pahelwan, "The old woman is selfish even after death. Look at her - she will have a warm bath herself but make poor Pedro take those icy dips in the river!"

After the bath a shroud was wrapped around the body and it was placed upon a plank of wood. Tarzan and Seth lifted it from the two front ends; the third at the back was shouldered by Dakter. Pahelwan was about to offer his shoulder for the fourth comer when Seth yelled, "Hey you mullah, don't you touch it! Our corpse will be polluted."

"Oh hell. If the old lady finds out that a Muslim shoulder carries her, she will leap out of the coffin," Tarzan said.

"Okay, give her a ride yourselves. But remember, it will only be a Muslim who prepares her pyre at the cremation ground. Come, come, my brothers-in-law, we are the ones who bring you into the world and again it is us who preside over your bodies while they turn into ashes-telling me, are you?"

Eventually a boy from the neighbourhood made the foursome and the last journey began. Pedro walked in front, carrying a basket containing all the material needed for the cremation rites. Next to him, wrapped in a thick blanket from head to toe, walked the priest. He had hated to leave home in this bitter cold and was thinking, "A doctor can refuse to attend, a lawyer can refuse to come, but curse our profession, which does not give the right of refusal! Besides, who knows if there will be anything to gain from this wretched fellow!"

Behind Pedro and the priest came Tarzan, Seth, Dakter and the boy, carrying the coffin. After them walked Pahelwan and a few others from the neighbourhood. The neighbours accompanied the funeral procession a short distance and then returned home.

Pedro walked straight ahead, carrying the funerary basket. At first he had thought that with his mother's death, he had been set free. But now it appeared that it had made him a homeless vagrant. The rope that had anchored him to the shore was broken and he was adrift in the flood of life. He would keep on drifting without any goal or safe shore as long as he lived. His mother used to curse him, heap abuse on him but occasionally did give him a blessing too. She would quarrel with him over the daily expenses nearly every day but at the end of the month it was she who gave him something, saved God knows how and when, for his cigarettes. Most of the time she sulked, angry with his ways, but sometimes she would hold him in her arms and give him a tight hug. From now onwards no one would mind his ways - no one to sulk nor to love him. As far as he was concerned, no other death need matter to him nor his own to anyone. He was alone in this journey - all alone, and the road was tough. Suddenly he looked back and the ground slipped from under his feet. He really was walking all alone, clutching the funerary basket. No one else was in sight - neither the priest nor the coffin nor even those who had held it aloft. What did it mean? Was he dreaming? Was this a trick played upon him by the Lord of Death? Eventually he caught sight of the priest lighting a cigarette at a shop in the distance and he breathed again. But where were the others? Had the earth swallowed them or the sky devoured them?

The priest, his cigarette lit, found him standing alone, frowning worriedly and said, "Listen, you. I don't know what is written in your fate. Those rakshashas must have slipped on the ice and dropped the body on the frozen ground. What has happened is very bad indeed."

In his heart Pedro also knew that he was ill-destined. The priest had not lied. But the riddle of their disappearance plagued his mind. How and where could they have vanished? Granted they might have slipped but would that bury them in the bowels of the earth?

The Brahmin mumbled a prayer in his faulty, ill-pronounced Sanskrit, "Oh Lord of Death, Shiva Shiva Shambhu, forgive me my transgressions!"

The lamp in Pedro's basket had been long extinguished. A streak of smoke rose from its blackened wick. Pedro was not only bewildered but quite frightened too.

Some more time passed and then he saw something - a faint outline resembling a coffin. He breathed a sigh of relief. At last his mother's coffin caught up with him. "Three have fallen!" Tarzan shouted as he came abreast. The priest's heart stopped. "Oh you demons! Did you let the corpse fall three times" ? God save us. Oh the Lord have mercy on me," he cried in horror.

"Oh no sir. Our lion Chandra has taken three wickets! Understand?"

"Shut up you rogue." Seth bit his lip trying to check his anger, "By the Holy Prophet, this is the limit."

Pahelwan explained to Pedro, "Listen you cursed fool! As we reached the Shahi Panwallah, it seemed as though a break had been applied to Tarzan's feet. The wretch stopped to listen to the commentary. We kept pleading with him to get a move on. The panwallah even went to the extent of laying his cap at his feet. When the people saw us listening to the commentary with the coffin, they began to curse us. But Tarzan's feet refused to budge. Finally the panwallah switched off his radio."

"Listen brothers. For the last seventy years this old lady never showed any urgency to reach her destination. So how does my ten minutes' delay matter now?" Tatzan defended himself.

"Tell him to hold his tongue!" Seth exploded, shaking with rage. "If he does not shut up, I'll throw the old woman down and run away from here."

The priest admonished Pedro, "Oh you rakshasa! Are you a man or a beast? I swear, this is the last time I ever ... but then why should you care?

Whose death need worry you?"

On reaching the cremation ground, Tarzan, Seth, Dakter and the boy lowered their burden to the ground. The Muslim contractor of cremations started building the pyre. Pedro awaited the priest's instructions.

Tarzan spoke up, "Did you hear this one'? This Dakter has a love affair going!" There were guffaws from all.

Pahelwan confronted Dakter, "Love? With whom?"

Tarzan intervened, "Hear the story from me. This fellow's "love" is going on with his boss's wife!" The boy from the neighborhood was slightly embarrassed.

"He does all their housework. Washes her saris and blouses. Presses clothes. Hey, do you get anything for your pains? Or is it for free?"

"See this fist? It will break all the teeth in your mouth. She is my mother," Dakter said angrily.

"Why do you taunt him?" Pahelwan asked Tarzan. "Tell me, do you or do you not frequent your factory owner's house?

"My foot! Going to the house will not make me a manager. I have no desire to become a leader like you." And raising his voice so that everyone could hear, he continued, "Did you people hear this? This Pahelwan has given up his "leadery"!"

"Since when?" Dakter was surprised.

"Ever since the day the police arrested him while he was pasting pro-Pakistani posters on the city walls. Those who had entrusted him with the task spread the word that he was caught picking pockets."

Everyone laughed. A shadow of annoyance passed over Pahelwan's face for a moment.

"Get up and place the body on the pyre," the priest's words roused them and all the four stood up.

"We are ready," Tarzan said, "If you like, for you too!" But the priest did not hear him.

Flames were no longer rising from the pyre, just the glowing embers, crackling and disintegrating into ashes. Seth laid his hand on Pedro's shoulder, "Come, what is the use of staring at this heap?"

"Let's go." Pedro leaned on him and started walking way.

"Where is Tarzan?" he asked.

"Has he also bolted like the priest and the boy? But where could he have gone?" Dakter asked.

"I know," Pahelwan said, "the wretched fellow must be listening to the commentary somewhere. Can't tell the difference between mid-on and silly mid-on but must pretend to be an authority on cricket! He should not have let the community down like this."

"He certainly shouldn't have," Seth agreed.

They reached the boundary of the cremation ground. Pedro, Dakter and Seth had turned back to bow to the smouldering pyre when Pahelwan shouted, "Look! Who is that behind the chinar?"

"Oh, if it isn't our own Tarzan!" said Dakter. All the four walked back to him.

Tarzan sat against the chinar, stating at the still smoke still hanging in the air. Pedro took his hand and said, "Come along, yaar, what's there to wait for?" Tarzan drew Pedro to himself and hugging him, said, "You lit your mother's pyre today with your own hands, but I was too small at that time - just six or seven months old. I could not even do this."

Both Tarzan and Pedro burst into tears. They cried bitterly. Dakter and Pahelwan did not know how to handle this new development. Dakter was ready to scold them but Pahelwan checked him with a gesture, "Let them be. That is what all of us need - a good cry."

Tomorrow?

Harikrishna Kaul

As the boys went into their classrooms after the prayers, Sula of Class IV said to Makhana, "Learnt the multiplication tables set by Nilakanth, have you?"

"Tried to, but just can't memorise the damn things."

"What shall we do? Lord Yama's own messenger he is." Makhana's face turned pale. Sula laughed carelessly and handed something to him quietly. "Here, rub it on your hands."

"What is it?"

"Sheep's fat. Go on, apply it on your hand, then the caning will not hurt."

"Swear by your father?" Makhana was rather incredulous.

"May my father die if I am not telling the truth. Look, I am also applying it on my hands."

The two friends went on quietly applying the fat on their palms through the first four periods and the recess. Nilakanth's period came after the recess. As soon as he entered the Class room he look off his turban and placed it on the broken down shell of a cupboard. Then he sat down, unbuttoned his coat and shirt and began to scratch his hairy chest. Spreading out his legs, he farted while asking the boys to recite the multiplication tables. After six boys, came Makhana's turn. He did all right initially but then be faltered. Nilakanth grabbed his ear and pulling him, dragged him towards himself. Makhana stole a glance at his hands.

They were glistening with fat. But Nilakanth did not cane him. He surveyed the class and his eye fell on Sula who appeared to be the most well built and tough and he said. “Hey you, Sula fatso, come here. Give this Makhana a ride on your back." Sula had been quietly trying to memorise his tables. Hearing the order, he folded his book and put it back in the bundle on the piece of cloth in which he carried them. He stood up and glancing at Makhana gave a chuckle and lifted him on his back. Nilakanth pulled up Makhana's shirt and began to cane the tender flesh with a thin stick. Makhana screamed, "Oh father dear, oh mother mine? I'm dead. Sir, I'll memorise it tomorrow, I promise I will. Oh my father, I'm dead. Sir? Masterji? Please spare me today sir, may God send all your misfortunes upon me! Sir, Masterji! May I die instead of you, Masterji! Tomorrow I'll have everything by heart, you will see sir."

"Are you telling the truth?" Nilakanth asked.

"The truth sir? If I don't have them at the tip of my tongue tomorrow, please skin me alive."

"In that case, let's leave him," Nilakanth told Sula and then fumed to the class, "Will all of you have learnt the tables till No. 16 tomorrow?"

"Yes, sir," everyone yelled - Sula the loudest.

"All those who did not know them today, will now touch their ear lobes in shame." Half a dozen boys did so and

Makhana before everyone else.

At 4 p.m. the two friends left school to walk home together. Just as Sula began to say something, Makhana snapped at him, "Shut up, you??? I've seen your friendship very well!"

“Ah, ha! Did we carry you on our back of our own wish? We only did what Masterji asked us to do."

"Rogue! Showing off the sheep's fat indeed!"

"How was I to know that he would hit your bottom? You should have applied the fat on your buttocks - then it would not have hurt."

"Keep your mouth shut or I'll break all your teeth!"

They had reached the main road and standing there was the Convent School bus. The children were alighting while their mothers waited for them. The boys and girls were in uniform - white shirts, red neckties, red socks, black shoes and green shorts or skirts. They all carried little lunch boxes. Something happened to Makhana - he kept staring at a blue-eyed little girl. Sula was watching a little boy with hair like silk and milk white legs. It appeared that the little boy had not eaten his lunch because his mother was telling him, "But why didn't you tell me that you do not like kofta? I would have given you some mutton. Or a couple of eggs. There were some pieces of fish left over from yesterday's curry you could have had those. But why did you have to starve yourself?"

The boy only smiled in return.

Suddenly a thought came to Sula and he asked, "What did they cook in your home today?"

"Two kinds of greens."

"Just as wretched as I thought!"

Perhaps Makhana did not hear him. He was wondering, "Who could the blue-eyed one be? Whose child was she?"

The next day, when the bell rang and all the boys assembled in the compound for prayers, Sula happened to look back. He turned deathly pale. He saw his father talking to the Headmaster outside the school gate. His instinct was to dash out, but the peon stood at the gate menacingly. The lump of fat still lay in his pocket - he had not yet used it on his hands. After a while the Headmaster returned and the peon shut the gate.

"Sula of Class IV will step out," the Headmaster ordered. Sula's knees trembled as he moved forward.

"Do you know what this fellow Sula was doing at home yesterday?" the Headmaster addressed the boys, swinging his cane.

"No, sir," the boys shouted at the top of their voices.

"A regular riot he has created at home last evening! Broken the pots and pans and bitten his mother's thumb. And do you know why?"

"No, sir."

"He told his parents that he wanted hot rice and curry!"

"Hot rice and curry? Ha ha ha . . ." all the boys laughed.

"Should he have asked for these things?"

"No, sir."

"If they give you cold rice, that is what you should eat. If they give you greens, that is what you must eat. If they give you nothing, you must keep quiet - isn't that so?"

"Yes, sir."

The Headmaster proceeded to cane Sula - a dozen times on each hand and finally asked the Maulvi Saheb to bite his left thumb. Sula bore the pain of the beatings somehow, but the bite drew a shriek from him and he fell down in a heap. Two hard kicks from the Headmaster sent him back to his place in the line.

The prayers began. Two boys from Class V - Javed Ahmad and Ashok Kumar stepped forward and started to sing in Urdu; Lab pe ati hai dua banke tamanna meri, zindagi shams ki soorat ho khudaya meri. This wish comes as a prayer upon my lips. Oh Lord, make my life like that of the candle.

The rest of the boys repeated the words after them as loudly as they could. Sula, his voice choked with sobs, sang through his tears, Door duniya ka mere dum se andhera ho jai, har jagah mere chamakne se ujala ho jai! May the darkness of the world be dispelled through me. May there be light everywhere that I shine.

The prayers over, the boys went to their respective classes. Seeing Sula's small, reddened eyes, Makhana's heart softened towards him and all of yesterday's anger was washed away. What if his own father were alive today? He would also have been coming to school sometimes to have him thrashed. Good that he had only a mother. She beat him, no doubt, but would not come to the school with a complaint. But the very next moment he remembered Nilakanth and he also remembered that he had still not memorised the tables. Asking Sula for the fat did not seem quite tight. Besides, he had no faith in it any, more. The problem exercised his mind, but eventually he thought his own remedy the best: he took the Goddess Kali’s name seven times and tied a knot in his shirt.

After the recess, Nilakanth entered the classroom. As usual, he took off his turban and put it on the broken down cupboard, slipped his feet out of his pumps and sat cross-legged in his chair. Scratching his head, he asked the boys to recite the tables one by one. While the first boy was doing so, Makhana suddenly stood up.

"What thunderbolt has hit you now?"

Makhana lifted his little finger, " "Pass", sir."

"Oh "pass" indeed! Sit down at once or I'll thrash you."

Makhana sat down, but, after a few minutes stood up again, "Sir, Mastetji, I'm bursting! Terrible "pass" sir!"

"No mischief before me! Or I’ll draw it out through your bottom! "

'Sir I'm telling the truth, Masterji. It is the big "pass", sir!"

Nilakanth looked Makhana square in the face. Makhana's eyes seemed to glitter with tears. He thought that he was telling the truth and so let him go. Once in the toilet, Makhana began to think- there certainly was something in the business of tying a knot in your shirt, or why else would he get the urge for the big "pass" all of a sudden? Hadn't he already relieved himself at home in the morning? Actually, the great Kali is not the one to leave her devotee in a tight situation?by the time he went back to the classroom, Nilakanth's period would be over.

The last bell rang at 4 p.m. Sula and Makhana left to go home. Reaching the main road, Sula would have continued to walk on, but Makhana stopped him with, "Wait. Let's stop for the Convent bus."

"To hell with it! We only get a beating later on." Makhana was quiet. Sula took his arm and pulled him along. But Makhana's feet refused to budge. Eventually Sula left on his own. He had taken only a couple of steps when he saw a few people gambling. He stopped to watch the game.

After a few minutes the Convent bus came. And out trotted the children in their shorts/shirts/socks/shoes/ties. After five or six children came the blue-eyed girl. Handing over the lunch box and attache case of books to her mother, she tightened her skirt belt. Makhana's heart pounded against his ribs as if the Headmaster had made him do eight runs of the school yard. As he was looking at her she disappeared with her mother in the halwai's alley.

The next day, school went well till the recess when suddenly the cry went round that two boys had drowned while bathing in the river near Habba Kadal. The bell at the end of the recess was rung late and the teachers had all the boys assemble in the compound and fall in line just as they did for prayers. After a while, the Headmaster came and delivered a lecture. The boys must not go to the ghat to bathe in the Veth because the river was infested with crocodiles; the crocodile is a riverine animal and resembles a lizard but is much bigger in size and as soon as a boy enters the Veth, its jaws close on his legs and he is dragged down; from the word "crocodile", came the phrase, "crocodile tears" . . . .

Meanwhile the Second Master came and proceeded to put the stamp of the school on every boy's thigh while the Headmaster spoke on: "The school stamp is being put on your thighs so that every morning we can examine it and if it is found missing or washed away from anyone's skin, he will be given a tharshing with stinging nettles."

When the Second Master was through with the task of stamping, the school was declared closed for the day.

As they were going home, Makhana said to Sula, "Supposing we tell them that we had a bath under the tap? How can they tell?"

"Stupid! Do you think they are fools? Don't they know there is no water in the taps? What wisdom will you show them then?"

Makhana pulled his shorts up and said, "Look, how well this brand of a slave suits us!"

"Aren't the legs of goats hanging at the butcher's shop stamped similarly?"

Reaching the main road, Makhana stopped, saying, "Today we were saved from Nilakanth the Crocodile's period."

"Oh yes."

"Did he ask you your tables?"

"No, I too was saved by the skin of my teeth."

"Swear by your father?"

"By my father's death I swear"

"How did you manage it?"

"He asked me to press his head."

For a while they were silent and then Makhana spoke, '"The bus has not come today."

"How can it come yet? Weren't we let off early? Come, let's go."

"Let's wait, shall we?”

"No, tomorrow the Crocodile will certainly demand the tables."

Makhana had developed a certain faith in the efficacy of the shirt knot. So he replied carelessly, "Oh, come on. Tomorrow is a long way off."

Tomorrow carne and went and so it went on for a long time. The Form Master was supposed to check the boys' before the prayers every morning and he asked them to show him the stamp. It had gone in several cases and on some only a faint mark remained. But it was still fresh on Makhana's and Sula's thighs as if newly made. There were welts of grime around the mark, throwing it into greater relief. The Form Master understood that these two had followed the Headmaster's order; to the letter, while the others had had an occasional dip. He was very pleased with them, and letting them off, asked both of them to go to his house where a carpenter was at work.

Sula and Makhana went off enthusiastically. They were to keep handing the material?frames, planks, and nails to the carpenter as he worked, fill water in his hookah, tobacco in the chillum, place a live charcoal from the kangri on it and take puffs till the tobacco was properly lit. Carrying beams, Makhana's shirt got torn. Sula had been wise?he had taken his off and worked in his shorts.

At about 4 p.m., the two picked up their bundles of books and left to go home. At the main road, Makhana's feet automatically came to a halt. Sula gave a chuckle and stopped too. After a while the Convent bus came and the children descended. Today they were in their winter uniforms?black shoes, red socks, grey flannel trousers, grey sweaters, white shirts, red ties and dark cherry blazers. On their top left coat pockets was the school badge. Makhana strained his eyes but could not locate the blue?eyed girl.

"Come on, let's go. It is late and I am cold."

Makhana seemed to wake up at Sula's remark. He too was feeling cold and the two turned homewards.

After a month or so, the school closed for the winter vacation. When it reopened, there was still some snow around. Before the bell rang, the boys played and had snow fights. Sula and Makhana buried a number of boys in the snow and thrust snowballs through the shirt fronts of several others. Then they made three snowmen, resembling the Headmaster, Nilakanth and the Maulvi Saheb. In the bustle of the game, they came into their own and seemed to realise their worth for the first time. Hardly anyone escaped their attention. The high point of the morning was their dragging Ashok Kumar and Javed Ahmad of Class V on the snow. This thrilled them with an animal pleasure. Their happiness lasted till the fourth period. For the first two periods no one turned up to teach them. The third was Maulvi Saheb's. He demanded walnuts from the Shivratri festivities from the Pandit boys and forgot to check the work assigned for the long winter vacation. But the Second Master in the fourth period demanded work. The pallor of death spread on the faces of several boys. Makhana quickly tied a knot in his shirt. Sula did not have the lump of fat with him. He looked appealingly at the Second Master who made all the boys, including him and Makhana, who had not done the winter assignment, stand up. Then he beat the stove pipes wish a stick and collecting the accumulated soot, smeared their faces with it. The Monitor was ordered to take them round all the classes. Makhana heaved a sigh of relief at having escaped a beating. Now he was fully convinced of the secret power of the shirt knot. As they went down the stairs, he told Sula, "Saw a film with my cousin on Shivratri. There was a black giant in it just like you!"

"You should see your own face! You look like the devil himself!"

Led by the Monitor, they came to Class V first of all. Seeing them, the boys and the teacher burst into laughter, in which they also joined in sheepishly. Their next stop was Class IV which was be taught by Nilakanth, who boxed their ears. A few boys started to laugh but Sula gave them such a malevolent look that the smiles froze on their lips. After this the Monitor took them to Class II, which was being taught by the Maulvi Saheb at that time. He showered blows on some and obscenities on others. While giving Makhana a hard blow he admonished him, "Don't you dare forget to get the Shivmtri walnuts tomorrow!"

In the Upper First, Makhana quietly pinched the arm of the Black Giant next to him and a cry escaped him, at which the Master gave him several hard slaps. In the Lower First, Sula upset a bottle of ink belonging to child sitting in the front row, but the child was too scared of him to even utter a whimper of protest. When they were back in their class after the round, the Second Master made them catch their ear lobes to express shame and with firm instructions to get their work with them tomorrow without fail, dismissed them.

Tomorrow went by, then another tomorrow and so it went on for the next five years. The name of the school was changed. It became the Government Lower Middle School. But it still had only five classes and Sula and Makhana still remained in Class IV. The warm autumn sun was very pleasant and these two had been put to work by the Maulvi Saheb. Sula was scratching his back and haunches with his nails. Makhana was squeezing out the pus from the boils on his thighs. The Maulvi Saheb's eyes were half-closed with relief. The other boys were engaged in games of noughts and crosses played on slates. The Monitor stood at the door on the look out for the Headmaster. This was the last period and they were let off after this. Makhana bought a cigarette for one paisa from the shop outside the school and the two friends took rums taking puffs from it.

"Come on, hurry. Let's leave the books at home and play with marbles," Sula said.

"No, let's finish the cigarette first. On the main road someone might see us smoking."

"That's a lie, you rogue, if your father were alive, you would make him fill tobacco in your chillum, I'm certain. I

know what's bugging you?you think it is too early for her to come!" Makhana just grinned. Finishing the cigarette, they

walked to the main road. The Convent bus had arrived. The children descended and then left with their mothers. The bus left, but Makhana and Sula remained. Makhana asked Sula to buy two - paisa worth of roasted soyabeans. "There she comes!" Sula's exclamation made Makhana forget to munch. His heart beat faster as he stared at her unblinkingly. Reaching the halwai's shop, she dismounted her bicycle. Her attache case of books was on its carrier and in her hand she carried a hockey stick. She wore white socks and PT shoes. Her white skirt hemline reached just above her knees. Over her white shirt, she wore a red nylon cardigan. Her hair fell over her shoulders.

"How she has grown! How different she looks!" Sula nudged Makhana.

"Only her eyes are the same?as blue as ever," Makhana drew a deep sigh, "What a little girl she used to be!"

"How little? Just as little as we used to be. But they say she is to appear for her matriculation this year."

“Swear on your father?" Sula seemed to jump out of his skin.

"May my father die if I tell a lie," Makhana swore.

"This is what is called luck!"

`"They say she is the captain of the school hockey team too."

Suddenly Sula thought of something. He asked, "Hey listen, didn't they take four annas from each of us for sports equipment last month? What did they do with the money?"

"Just look where this chap has gone!" Makhana was furious, "I’m talking of something serious and he is off on a totally different track - after all, what can one expect from him!"

Next year the name of the school changed again. Now it was the Nehru Memorial Government Lower Middle School.

Sula asked Makhana, "What does this Nehru Memorial mean?"

"Nehruji is dead, that is why our school has been named after him," Makhana answered his question.

"Oh that I understood very well but what does "Memorial" mean?"

"How the devil should I know?"

"To me it sounds like an obscenity."

"What the hell is the matter with you?" Makhana lost his temper, "I'll report you to the Headmaster?tell him that this fellow is abusing the leader of the Kashmiri Pandits."

"Oh ho! Did I abuse him on my own? They themselves have given this obscene name to the school."

"How does that bother you? You just keep your mouth shut."

After the prayers, the Headmaster made an announcement: the Maulvi Saheb was retiring from service that day; he would not be coming to school the next day. Then he spoke at length of his competence and gentle qualities. The boys understood nothing of it. The Headmaster then made a request for the Maulvi Saheb to say a few words of advice to the boys, at which he stepped forward and began, but broke down after just a few words. Taking a piece of cloth from his sherwani pocket, he wiped his tears. Placing the same cloth on his nose, he blew hard and drew the snot on it and rubbing the cloth between his fingers till it was absorbed, folded it afresh and put it back in his pocket.

While climbing the stairs of the class, Makhana asked Sula, "Hey, why did the Maulvi Saheb weep?"

"Shouldn't he weep? The poor man must be feeling bad about leaving his job." Sula said.

"Couldn't it be that he was sorry about beating us so much?"

"Maybe that is why, who knows."

"Anyway, good riddance! God has delivered us from him."

"Oh but will he who comes to replace him be any better for us? All these bastards are the same."

Maulvi Saheb came to Class IV as usual in his period. He was eloquent : "My dear boys, you will be very happy to see me gone. You must have a lot of resentment against me because I used to beat you, but remember a teacher's beating is not a beating, it is like being given food and nourishment. And this stick is not a stick, it is a giver of wisdom. I had no hatred for you rather there was love for you all in my heart. That is why I liked to drill sense into you with this, my symbol of wisdom."

The boys listened in silence. He went on and on and finally concluded with, "All right, now 1 shall hit each one of you on the hand with this stick for the last time, so that you will always remember my love for you."

The Maulvi Saheb retired, but there was no immediate replacement for him. The next day, the Headmaster himself took their class. As his glance fell on Sula, he seemed to remember something, "Hey, you there. What's your name?" "Sula, sir."

"All right, Sula, get up and go to my house. Do you know where I live?"

"Yes, Sir."

"Very well. Now listen, our servant went home to his village yesterday. Why don't you go and take our cow out, lead her to some garden." Sula rose with alacrity and asked, "Sir, shall I leave my books here or take them along?"

"No, no, take the books with you. At 4 o'clock you can go home from there. But wait. Take someone with you."

"I can take Makhana with me, sir."

"And who may Makhana be?"

"Me, sir," Makhana rose with a grin.

"Ah, that's very good. Run along then, both of you."

The two picked up their load of books and left. They went to the Headmaster's residence and drove the cow out, leading it to a distant field. The cow began to graze, her mouth clinging to the green grass, while the two started playing hop-scotch.

"Hey, did you see how fat the Headmaster's wife is?"

"Shouldn't she grow fat? With a cow at home, she must be drinking milk by the bucket every day!"

"They said the servant would be back after four days. Well, why should we mind? That is four days well taken care of! And if they ask us to write a composition on "Cow" in the examination, just think of it!"

"Oh yes. Look, this cow really has two cars, two eyes, four legs and one tail! Don't they also write, 'a cow chews

cud?' What does that mean' ?"

"Maybe it is something to do with dung."

"Forget it. Besides, if the Headmaster is pleased with us, he will certainly pass us, composition or no composition," said Makhana.

"Tomorrow I’ll get the marbles with me. There's no fun in this hop?scotch."

"Ah ha?that"ll be fun." Makhana jumped with joy in anticipation.

On the fourth day, while playing with marbles, a sigh escaped Makhana and he said, 'The Headmaster's wife said their servant would be returning from the village today."

" That means we shall have to attend school tomorrow?"

Sula's knees became wobbly with dismay.

"But let us loaf tomorrow too. We shall tell them at home that we have to take the Headmaster's cow out again."

"By father, now you are talking sense!" Makhana's spirits soared and he shouted, "Here - that's my turn!"

Tomorrow came and went and so it went on for another five years.