PN Kachru

P.N. Kachru

Artist of Kashmir from Rainawari, Srinagar.

Photo Courtesy: Mag. Kapil Kaul

Mr. P.N. Kachru is an artist of national repute. He is a graduate from the Punjab University. He kept terms in Post-graduation in English Literature, 1945-46, in the same university. He earned a Diploma in Fine Arts (Painting) in 1944. He has been the founder member of the National Cultural Front established in November, 1947 to combat the tribal storm-troopers who invaded Kashmir in October, 1947. He has also been the founder member of Progressive Artists Association, The National Cultural Congress, J&K State Cultural Congress, the J&K Artists Association and the visionaries. He has held numerous exhibitions of his paintings at various art centres in Delhi, Bombay, Lucknow and Srinagar. He has also participated in numerous national exhibitions held by Lalit Kala Academy, New Delhi, Hyderabad Art Society, Academy of Fine Arts, Calcutta, Bombay Art Sociery et al. He has participated and presented papers on Kashmiri art and culture in several national seminars.

He shot up in the art scenario of the country when he earned a number of awards from Hyderabad Art Societal and Academy of Art, Culture and Languages, J&K State. In 1988 he was invested with "the Veteran Artists" Award by AIFACS, New Delhi.

Image Gallery: https://koausa.org/site/gallery/categories.php?cat_id=288

Résumé

1. Born in Srinagar, Kashmir

2. Education:

a. Graduate, 1944, Punjab Unive rsity

rsity

b. Kept terms in Post Graduation in English Literature, 1945-46, Punjab University.

c. Dipoma in Fine Arts (Painting), 1944.

3. Founder Member:

a. The National Cultural Front, November 1947.

b. Progressive Artists Association, September 1948.

c. The National Cultural Congress, 1950.

d. J&K State Cultura Congress, 1953.

e. The J&K Artists Association, 1954.

4. Exhibitions, Group Participations:

a. Progressive Artists Association, Srinagar, May 1949

b. Progressive Artists Association New Delhi, Bombay & ucknow, September, 1949.

c. Progressive Artists Associations – 1950, 1951, 1953 and 1955.

d. J&K Artists Association, Srinagar and Jammu, 1954.

e. Kashmir Art Society, 1958.

f. Academy of Art, Cuture and Languages, Srinagar, 1956, 1957, 1958, 1960 and 1964.

g. The Group of Three – Kachru, Kaul and Kishori, New Delhi, 1960.

h. The group of five – Srinagar, New Dehi & Bombay, 1964.

5. The National Participation:

a. National Exhibitions, Lalit Kala Academy, New Delhi 1958, 1959, 1964 & 1967.

b. All India (National) Exhibitions of Hyderabad Art Society, 1962, 1965 & 1968.

c. Academy of Fine Arts, Calcutta, 1960, 1962 & 1966.

d. Bombay Art Society, 1960.

6. One–man Exhibitions:

a. New Delhi – 1955, 1960, 1966, 1972, 1976, 1980 & 2002.

b. Calcutta – 1959, 1963 & 1965.

c. Bombay – 1955 & 1957.

7. Awards and Prizes:

a. Best painting of the year, 1959 award, Hyderabad Art Society.

b. First Prize, 1959 Hyderabad Art Society.

c. Prize, Academy of Art, Culture and Languages, J&K State, 1960.

d. First Prize, Academy of Art, Cuture and Languages, 1962, J&K State.

e. “The Vetran Artists” award, 1988, AIFACS, New Delhi.

8. Handicrafts:

Design Development:

a) Design Development Scheme formation, 1956, 1957.

b) Design development of handicrafts, 1958 to 1980.

Craft Research Programmes:

Kashmir:

a) Research in the :Kani Shawl”.

b) Woodcrafts – folk traditions, Architectural (Medieval) & Modern.

c) Kashmir glazed potteries.

d) Namdha Felt making, formation and quality control.

e) Research and survey of Kashmir carpets.

f) Research in vegetable dyes.

Jammu:

a) First survey of handicrafts 1970.

b) Research and survey of cotton prints – the Samba prints.

c) Research and survey of ancient Chikri woodcrafts of Thana Mandi.

d) Survey of felt makers of Saurashtra (Kutch), a project from Gujarat Govt., 1986.

9. Writings and Articles:

a. Modern Kashmir Art movement and its founders.

b. Kashmir Buddhist sites – Harwan, Wushkar and Hutmar (Matan).

c. Kashmir School of Terra Cottas – the Wushkar school.

d. Megalithic site of Burzhom, Kashmir.

e. Burzhom and Indus vally civilization.

f. The living tradition of India-crafts of Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh – Chapters of Papiermache and wood crafts, Mapin Publications Pvt. Ltd., Ahmedabad.

g. Survey Report on felt makers of Kutch (Saurashtra), commissioned by Handloom and Handicrafts Export Corporation, Govt. of Gujarat.

h. “Stein’s search for Codex Archetypus” – the paper was read out on the occasion of Remembering Sir Aurel Stein.

Featured Collections

Lal Ded and Kashmiri Chroniclers

by P.N. Kachru

The Indian tradition in chronicle writing would have suffered from a great vacuum but for the genius of the lone ranger named Kalhan Pandit of the mid-twelfth century Kashmir. While honouring his lone leadership in the tradition of Indian historiography, Kalhana too has not been able to prove himself to be a dispassionate surveyor as behoven of an ideal chronicler and historiographer. Although he has thrown light on an assortment of clans and groups who wielded power, intrigued and conspired, but at the same time he has remained aloof and unobservant of the mainstream evolution of the society and its development of socio-intellectual thought. The luminaries and philosophers who founded, propagated, built and broadened the socio-cultural vision of the society, have remained obliterated from Kalhana's chronicleship. No doubt stray references to Kshemendra's Nripavali and mere passing mention of Anandavardhana and Ratnakara, it leaves an ocean of history in oblivion. The emergence of mighty movement of Kashmiri philosopher and thinkers who, not only founded the values of Sarvastivaad and Madhyamika movement, but also laid its foundations in Central Asian, Tibetan and West Chinese regions. As many as eighty philosophers and scholars have been identified who have founded the movements in these regions, while hundreds of them have revolutionized the Kashmirian society. Not to speak of only such scholars who enriched the Buddhist thought, but also those who led a thousand BC old Paashupata and Kaalamukhathought to the highest pinnacles of Shaivic philosophy. The great geniuses and seers like Vasugupta, and Utplacharya and the founder of Shaivic philosophy, Somanandanatha, have not found any place in Kalhana's chronicle. Even the world genius like Abhinauguptapaada, who created history in the neighbourhood times of the chronicler, does not find any place in Rajatarangini.However. Kalhana's to a greater extent his impartial approach towards the events of history is the chief ornament, which his followers have brazenfacedly done with and, instead have become the committed chroniclers of court intrigues, partisans and prejudicial commentators on palace intrigues.

Jona Raj (1459 AD), the neighbour-historian of Lal Ded, while surveying through the leaves of his Dvitiya Rajatarangini, does not even mention her name who had left her mortal frame only a few years before. On the other hand, for his obvious commitments, could spare his page to Nundarishi who was a mere toddler during the concluding years of Lal Ded's life. Jona Raj states 'Malls Noordeen yawanaanaam paramagurum'-the chiefest guru of Muslims, on whom imprisonment was imposed by the King Sultan Ali Shah during 1413-16 AD. Shrivara, in his Zaina Rajatarangini (1459 - 86 AD), Prajyabhat in his Rajavalipataka (1486 - 1513 AD) and his pupil Shuka in his Rajatarangini, all of them have remained discriminatingly unobservant of this genius of the times. These historians cannot be left uncensored for their negligence towards the culture of the land.

The Persian chronicles like Tarikh-i-Rashidi (1546 AD) of Mirza Duglat, Baharistan-i-Shahi (1614 AD), Tarikh-i-Kashmir (1617-18 AD) of Haider Malik of Chadura, all these have followed the foot steps of their Sanskrit historians who preceded them by remaining discretely silent over the life of Lal Ded. Her personality became a direct victim of the mutilation through a prejudicial interpretation that originated from a factual incident quoted by Jona Raj in his Rajatarangini. He writes that dining a hunting programme in the forests, Prince Shihab-ud-Din was confronted by a group of threeyoginis. The chief of them (nayika) came forward and offered the prince a cupful of wine. Almost all the subsequent chroniclers carry on with the tale through the pages of their histories, wherein a leading yogini offers a cupful to the Sultan; but these authors change the contents of the cup either into juice or milk, thus hiding the fact and saving the Sultan from the exposure of having committed an un-Islamic act. Mirza Duglat in his Tarikh-i-Rashidi (1546 AD), remains discretely silent on the issue while Baharistan-i-Shahi (1614 AD) turns the cup of wine into a cup of juice. Later on another historian, Hyder Malik of Chadura, in his Tarikh-i-Kashmir (1617-18 AD) changes the cup of juice into a cup of milk. Furthermore, these expressions of theirs exhibit their ignorance and blindness to the knowledge, not knowing that the wine being one of the prime accessories for consecration in the shakta practice and worship. It becomes glaringly obvious that these historians, while interfering with the history, projected their prejudices and fundamentalist feelings in belying, misshaping and mutilating the events.

This process of mishandling and mutilation proceeded further ravageously. The meeting of a yogini with the Sultan is turned, as late as in mid-seventeenth century, into the meeting in the forest with Lal Ded herself. Baba Dawood Mishakati in his Asrar-ul-abraar (1654 AD), narrates that Sultan Alla-ud-Din's elder son, Shihab-ud-Din, during his hunting tour into the forest, met with Lal Ded who, on occasions, would roam into the forest. She asked Shihab-ud-Din and his three colleagues to rest a while, and offering him (the Sultan) a cupful of juice, which she got through nowhere. Further down the years another historian, Narayan Kaul Ajiz in his Muntakhib-ul-Tawareekh (1710 AD) remains discretely silent on this event. Rafi-ud-Din Gafil, in his Navadir-e-Akhbar (1723 AD), repeats the episodes of the forest but instead that of Lal Ded mentions the appearance of a saintly woman from nowhere.

This craft of manipulative chronicleship continued to slip down the mire and groped through the darkness for the stories like the meeting between Lal Ded and Mir Sayyed Ali Hamadani. No doubt, Khwaja Azam Dedmari in his Waqiyat-e-Kashmir (1735-36) has referred to the story, but thanks to him and his investigative method, the Khwaja declared that after inquiry and investigation, the story could not be proved out to be correct.

Despite this authenticative declaration of Azam Dedmari in mid-18th century, it was as late as in mid-19th century that Birbal Kachroo in his Majmua-al-Tawaiikh described the meeting of Lal Ded and Mir Sayyed Ali Hamadani in a bazaar, and also stated the former's plunge into the flaming oven of a nearby baker.

Although the statements of Birbal Kachroo are flimsy enough to stand the tests of inquiry established by his predecessor Azam Dedmari only hundred years before him, it becomes necessary on our part to put Kachroo's statements to proper analysis and to a thorough dissection in order to straighten the events. The historian's statement creates an additional alarm and curiosity, as it was for the first time after more than four hundred and fifty years that the event was revealed to the author, though bereft of any proof of historic investigation.

Firstly, almost all the earlier chronicles starting from Jona Rajatarangini down to mid-17th century, have remained

silent about Lal Ded, it was first of all in Asrar-ul Abrar in 1654 AD that Baba Dawood Mishkati replaces the name of the nayika of the forest with the name of Lal Ded. Again, later on, Narain Kaul Ajiz (1710 AD), Azam Dedmari (1736.AD) and Mohammad. Aslam, till late 18th century have remained silent on the issue of the meeting with Mir Sayyed Ali Hamadani. Therefore Birbal Kachroo’s statement stands unrelated and untenable.

Secondly, the dating of contemporaneity also does not indicate any synchronization. Excepting the statement of Azam Dedmari, all the chroniclers have relied either o approximations or their surmises; and, therefore, cannot be relied upon. The only categoric and precise statement of her death is from Dedmari stating that Lal Ded passed away during the rule of Sultan Shihab-ud-Din that lasted from 1355 to 1373 AD. Even taking the concluding year of Sultan's rule as the year of Lal Ded's year of death, and corresponding to this very year (1373 AD) Mir Sayyed Ali Hamadani was in the process of movement, along with his seven hundred associates, to enter Kashmir valley for taking refuge from Taimur's tyrannical tests of riding the blazing metal horse. So there could not be any possibility of his meeting with Lal Ded, she just then having left her mortal frame. This analysis of dating further lends strength to Dedmari's investigative statement.

Thirdly, probing further into the datings, the stay of Mir Sayyed Ali Hamadani, as documented by late Professor Jaya Lal Kaul, was from 1380 to 1386 AD. This statement of Professor Kaul further widens the gap of time between Lal Ded and Mir Sayyed Ali Hamadani.

My reliability on the two sources-Dedmari's Tarikh-I-Kashmir and late Professor Jaya Lal Kaul's book on Lal Ded-is based, in the first case, on author's decisive and categoric statement about precise period and, in second case, for late Professor's dispassionate observance and study of documents as an observer and an outsider to the happenings of history and its documentations. Not only this, the late Professor stands out, till today, the lone ranger who has stood firm to set right the record of fictitious chronicleship, of which Lal Ded became a direct victim.

REFERENCES

1. Dvitiya Rajatarangini shloka 348.

2. Shidhu chashakam

3. They use the Persian word afifah, which means a spiritual lady.

4. He calls it kasir-e-sharbati.

5. Terming it as kasir-e-shir.

6. And not as originally stated by Jonaraja.

7. The author's actual statement runs thus: "…………Dar aan zamaan Saltanti opisari mehtar ki Shahaab-ud-din bood dar jangle azmurh daur-e- shikaar me raft, dar aan zamaan Lalla Arifa gah gah dar dashto bayaabaan megushata roz-e-dar aan shikaar gaah ba-Shahaab-ud-din mulaaqat shod ……."

8-9. "Zani az alam namudaar shud"

10. "Nazdi arbaabi tehqiq saabit na shud"

11. "Lal Ded", by Prof. Jaya Lal Kaul, Sahitya Akademi publication.

The Kashmir Order Of The Architecture

by P. N. Kachru, New Delhi

The subject that I am dealing with is based on, and chiefly subservient to the Tattvas of materiality, as termed according to the KashmirShaivic concept. Arehitecture, in expression, being chiefly involved with the elements of these Tattvas which are termed as Mohabhutas, finds its expression only through these elements.

Parmashiva :

The basic reason for Is-ness, or all that is or exists in whatever form - experienced or inexperienced - is the flowering and projection ofParmashiva, the Ultimate Reality. This reality, in its ultimate aspect, is termed Cit or Parasamvit. This term is untranslatable in any other language, but in ordinary terminology it is translated as `consciousness'. According to great Shaiva author Jaidev Singh the term `consciousness' connotes subject - object relation; or knower - known duality. But `Chit' is not relational. It is just the changeless of all changing experience. It is Parasamvit.

Parasamvit :

It is the Self, sciring itself, or in Pratibignya terms, it is Self-sciring

Shaktitattva :

The moment His inherent nature vibrates as per its nature, it gives rise to pulsation. This aspect of His manifestation is termed as Cidrupini Shakti, the pulsating aspect of Shivatattva. Thus it is in the nature of Ultimate Reality to manifest through its Shaktitattva, which through its pulsation polarizes consciousness into I and This, or into aspect of subject and object relationship. These two Tattvas - Shivatattva and Shaktitiattva can never be distinguished between and disjointed. They remain forever united whether in creation or in dissolution. Strictly speaking Shiva - Shakti Tattva is not an emanation or Abhasa but the seed of all emanation.

The subject - object relationship, yet predominant with I-hood, generates the Will; and this experience of the essence of to Be is termed Sadashivatattva.

The `this' aspect of divine experience, when becoming more defined is symbolized as Ishwara-Tattva. In essence it is Unmesh or distinct blossoming, though still in non existencial state, of the universe. At this stage knowledge becomes predominant. There is clear idea of what is to be created. So far, the experience of Sadashiva is `I am this', and the experience of Ishwara is `This am I'. Here the equilibrium state of `I' and `This' experience is called Sadvidyatattva, or aspect of Shiva where `I' and `This' experience are equally and evenly held in balance. Upto this stage all the experience is ideal or in pure order. It is a manifestation in which real nature of the divine is without the coverings of limitation and distinction.

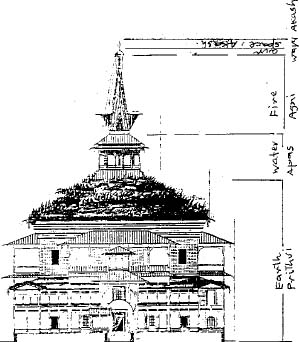

The experience of coverings and distinction ensues with the appearance ofMayatattva along with its five coverings, followed by the two tattvas (subject - object) of the limited individual - Purusha and Prakrati, Budhuddi, Ahmamkar and Manas are followed by fifteen elements of Gyanindriyas, Karmindriyas and Tanmatras, which herein are just skipped over without any elucidation and explanation, as the title of this subject - Kashmir Architecture - is directly based on the last five Tattvas of Materiality (Bhutas). TheseMahabhutas or Panchmahabhutas are, Akash (Space), Vayu (Air), Agni (Fire),Apas (Water) and Prithvi (Earth).

Architecture being a symbolical expression through these five Mahabhutas, the creative artist shaped and formed these elements through the following creative expressions. These are geometric in character. The ancient Neolithic culture, especially that of the Megalithic society has predominantly expressed and symbolized its thought through geometric patterns. Thus we find the first interpretation of material existence, the Panchmahabhutas, through these ancient geometric expressions.

Earth: It is symbolized by four sided rectilinear figure with four right angles. Following the evolution of Kashmiri mind, this right angular enclosure, with mental evolution, symbolized masculinity, the material world, physical energy, fertility, sexuality and procreation.

Water: Is symbolized by a circle which also later on signified wholeness, the spiritual perfection, feminine character and also formulated the base of architectuaral edifices of Megalithic cultures.

Fire: Is symbolized by an isosceles triangle with two longer sides with the apex at the top. Later on this triadic symbol represented the philosophic insignia for Kalamukha, Pashupata, Shaivagamic and Adi Tantric thoughts;thereby representing the triadic aspect - Mind, Body, Spirit, Shiva, Shakti, Nara and Love, Wisdom, Power.

Air: It is symbolized by the shape of a crescent.

Space: It is depicted by a drop with an apex upwards. The last twoMahabhutas, Air and Space, have been left uninterpreted due to subtle and finer experiences with these Mhabhutas.

While builing up the edifice, the ancient artist assembled these basic symbols into a monument that became the basis of our future architectural multiplicities. He assembled, visualized and built the edifice as illustrated here.

This Agamic structure was developed into various symbolic structures founded under the influence of Pashupata, Shaivagama and Adi Tantricphilosophies. Some of the Agamic and post Bhuddhist examples in script and situational conditions indicate the course of development of the basic symbolic structure symbolizing the Panchamahabhutas. The examples still in situations at Harwan Monastery and at Hemis Monastery in Ladakh are complete examples of architectural development in thought and in the variegated materials employed in the structures through the passage of time. The Buddhist concept has rendered a change in the Triangle of Fire that has been changed into a spire of thirteen converging tiers surmounted at the top by an umbrella (lotus) with a sphere depicting Formless realm. Herein main materials used are wood with unbaked mud - brick fillings.

The impression of Harwan Style

Timber and Mud-Brick Style

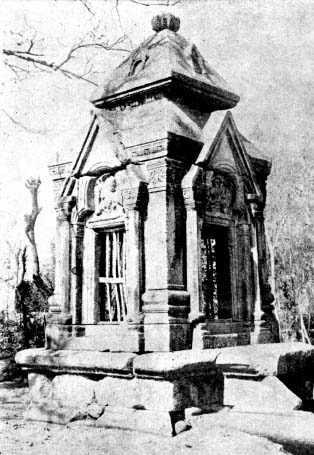

During pre Buddhist period the Shaivic thought traditionally used the wood and brick material. A lingering example of this structure is still existing in a remote village of south eastern Kashmir, that depicts the material employment of timber and unbaked mud - bricks. Although the multi - tiered spire, basically symbolizing fire, has been pigmied down through the course of the socio - phylosophical thought; but the Shikhara representing Space is duely poised at the top completing the Basic symbolization of Mahabhutas. Herein one can observe the structure built with timber and interspersed with mud - bricks.

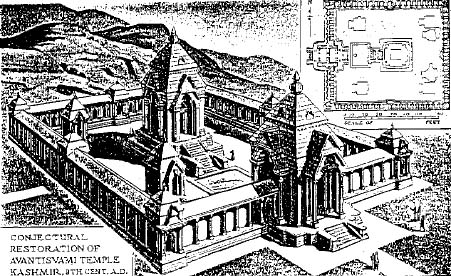

The periods of Karakota, Utpalas and Loharas lasted from early eighth century to eleventh century. This was the period of expansions and conquests beyond the territories of Kashmir when powerful cultural influences were attracted into the seat of power. Architects and sculptors sought their occupations in Pravarapura and Parihaspura, wherein they brought change into the employment of basic raw material. These craftsmen from East - Mediterranean cultures of Grecian and Asia Minor trends had already found their root amongst the Ghandharan and Gupta movements of northern India. They knew the masterly use of stone as their traditional raw material. They brought in a radical change in the structural establishments of local architecture. The tapering and sky - spiral slimness of Fire symbol was diminished to two - tier triangular roof due to the Hazardness involved in employment of massive stone blocks. No doubt, the change in medium of expression brought in massiveness and grandeur into the structures, but had to suffer the elimination of ethereal and spiritual heights and elevations.Martand, Avantipur and Parihaspur edifices wear the typical character of grandeur and massiveness but remain bereft of ethereal heights and elevations of spirituality.

Timber and Brick Style

Conjectural Restoration of Avantisvami Temple, Kashmir, 9th Cent. A.D.

By renowned artist and Art Historian Dr. Percy Brown.

The last vestiges of the local and traditional wooden architecture with its decorative excellence were reduced to ashes when the spiraling edifice of the palatial wood work of king Harsha (1089-1101 A.D.) was attacked and burnt down by rebellious masses. The palace situated in the vicinity of Habba Kadal was erected with forest wood from Kathleshwar and Tashvan forests.

By the end of eleventh century the mighty prowess and power of Karkota - Utpala - Lohara combine had fallen and had waned out. The Greco - Bhudhist and Ghandharan architects and sculptors had either migrated again or a major section of them having merged into the milieu and methods of popular architectural technology, and taken to the usage of timber and its cross - pier methodology with baked mud - brick insertions.

The Temple at Payar (massive stone)

Traditional Style : 1. Roof top of birch bark overlaid with thick piling of earth 2nd, 3rd and 4th of timber with baked-brick filling 1st (Ground) stone work.

Adherence to five basic element, though in a changed form.

The popular movement of the design, the usage of method and methodology, being so much embedded into the socio - cultural pattern that even after the establishment of Islamic order, all the successive movements of importance continued with expressions of the basic architectural design evolved on the basis of five gross elements (tattvas) of materiality. These fine examples of architectural grandeur are majestically imposing over the vistas of the valley. The wood and brick structures of the citizen's homes form a reflecting bee - line on the banks of river Vitasta and on the fringes of the cool back waters and canals of the Dal Lake. While writing about these structures, observes William Moorcroft (1819-1825) that "The houses are in general two or three stories high; they are built of unburnt bricks and timber."

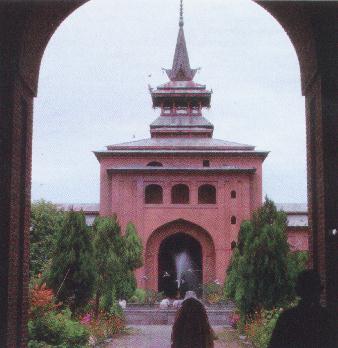

The well known Jama Masjid in the heart of Srinagar, presents a typical example wherein the symbolization, though varied in design, has been strictly adhered to the five gross elements of materiality - a) the main body, b) the balcony, c) the triangular spire, d) the lotus and e) the pinnacle (Shikhara). So is the case with other monumental and historic buildings of Rishi order, like the shrine of Nund Rishi (lately burnt down) at Cherari Sharief, the shrine at Aish-Muqam, shrine of Janbaz Saheb at Barramulla, the shrine of Baba Rishi at Gulmarg and the Rishi shrine at Pampore. The shrines of Batta Mol at Khanyar and the shrine of Naqshband Saheb at Khwaja BazarSrinagar; all these monuments are master specimens of the architecture. Needless to elucidate that the entire valley is dotted with many such shrines which are deep rooted into the cultural pattern of village life. While treading through the narrow bazar at Khrew village, Moorcroft observes "It has a bazar and two Ziarats or tombs of holy men, Shiekh Baba and Khwaja Maksud. These are small low structures, chiefly of wood, with a sort of wooden spire, capped with brass".

The Jama Masjid - note the Five Elements

The shrine of shan Hamdan at Mata-Kalighat 3rd Bridge, Srinagar note the original birch-bark and earth roofing. Timber and baked brick.

The Shrine at Pampore - note the Cross-piling of timber and baked brick filling.

Also note the Five basic Elements that constitute the structure.

The design and the Elements are strictly adhered in all the village and town shrines of the valley.

The Shrine of Dargah, Nasimbagh :

the typical structure presents an ideal derivation from the Kashmiri tradition, presenting yet another variation of the basic movement wherein all the five elements have been maintained excepting that the Earth symbol has been used for all the other four elements. This masterpiece of Kashmir order of Architecture, in by gone days, decorated the scintillating reflections of theDal Lake. Instead of rebuilding a greater masterpiece on the basis of this tradition, this grand structure of historical lineage has been effaced, obliterated and snatched away from the lap of Mother Kashmir. Those responsible for this un-Kashmiri act and carnage stand accused, for which the human culture and history will never forgive them for this onslaught onKashmiriat.

The Dargah of Nasim Bagh - Hazrat Bal

Kashmiri Pandits: Originators of Pahari-Kangra School of Art

by P. N. Kachru

"The Migrants"- this is the calling through which the authorities, the media, the publicity experts have stamped and marketed us, the dispossessed and hunted minority community of Kashmir. Being an artist and a man of culture I ponder over this calling differently. It is the migration that has given rise to the world cultures. Migrations have been the very basis and the reason for interaction between the races and tribes which sauntered on the surface of the most ancient soils. It is through migrations that different cultures, beliefs and philosophies interacted, got enriched, intermingled and mixed-up into the cauldron of commingled interaction through which human culture developed and turned the humankind worthy of calling itself civilised. The mighty drama of migratory comminglement of the three earliest sister civilisations, nourished the Indo-Mesopotamian culture. The massive migrations from the North, seeking warmer pastures, resulted in Indo-Aryan or Indo-Germanic culture that gave birth to vedic and the Zendic cultures. The great Indo-Bactro-Grecian culture that mixed-up and thrived in North-Western India and was responsible for the evolution of richest movements known as Gandhara and Mathura Schools which were destined to thrive into the golden age of Guptas. This cultural movement was responsible for infiltration and enrichment of North-India, which culminated into the aesthetic pinnacles of Kashmir School by establishing, now internationally known, the Wushker Baroque. These powerful trends were carried deeply by artists of Kashmir to little and greater Tibets, Central Asia, Mongolia and China.

Kashmir also had its share of migration-in and migration-out of various hordes, tribes and communities. The compromise of Nila with the migratory Kashypa and the regular combined expeditions towards North for the massacre and annihilation of Pishachas over the desert of Takiamakan; twice the destruction of Poomadishtan, the ancient city of Srinagar, by the Toonganees who were the ferocious crossbreed of Mongols and Chinese women, all these are the wellestablished facts of the cross-cultures of our history.

In recent and past history too, Kashmir had to pass through convulsive traumas brought in by fanatic converts of Mongol breed that led to the mass exodus of Brahmins, not once, but several times during the past centuries for adhering to their faith and philosophy. In such migrations there were some talented sculptors and painters who for centuries, had been responsible in establishing the Kashmir School of Sculpture and post-Gupta Schools of Pala Styles in Painting and were involved in spreading the movement to Tibet and Central Asian regions. Under the severe threat of proslytisation, and under the fear of being dubbed as creators of Idolatory, many artists it seems migrated for their safety into the neighbouring principalities of Himachal Pradesh. It was in this region of outer Himalayas where the Kashmir Schools of Arts thrived again and gave rise to gorgeous tapestry of art that became internationally known as Pahari movements, culminating into renowned Kangra Kalam or Kangra School of Painting.

This renaissance of Pahari culture was a post Moghul phenomena when the most of the Himachal Princedoms and states could independently look after their principalities. Most of the princes who had to be in attendance to the Moghul Court and had to eke out the resources of their states in order to cater to the whimsical demands of the monarch and also, had to fill the imperial coffers. This not only reduced the states to penury and poverty but also created local cultural vacuum. Most of the artistic talents hovered round the imperial court for seeking recognition and prosperity. This cultural exodus did a great disservice to the then leading northern schools. The artists got detached from their respective tradition, trend and locale and had to be subservient to the moods and methods of the monarch, besides reducing their talents to mere eulogy and falsehood. With the disintegration of the formality of the figures and the division of picture Imperial rule the Rajas and the Princes reverted to spaces-all these qualities were imposed with their principalities to reorganise their home-rule. The cultural scene of the Himachal principalities again . reverberated and started rejuvenating amongst its milleu and methods and traditions which we vitalised and reinterpreted by the Kashmir Movement. Thus the post Moghul vaccum was filled and augmented with the rich Baroque introduced by a talented fugitive Kashmiri artist family.

This family of Rajanaka (Razdan or Raina) Brahmins swept the entire region with their genius and were responsible for the introduction of one of the most romantic movements in fine art in almost all the principalities of jasrota, Basohli, Guler, Jummu, Chamb, Noorpur and Kangra. The family swept, influenced and led the movement from 1658 to the end of 19th century in almost all the centres of artactivity and enjoyed favourable position with various Rajas of the Pahari principalities.

Pandit Seu (Shiv) Raina was the ancestor of this family who, it is presumed, left Kashmir under the threat of forced conversion, sometime in mid 17th century (1660 AD) and settled in Guler during the reign of Raja Dalip Singh and Bikram Singh. Elucidates Mr. M. S. Randhawa (I. C. S.) "Proselytism to Islam was at its height during the last years of the reign of Aurangzeb. In the last quarter of the 17th century and the first quarter of the 18th century a number of Kashmiri Brahmins migrated from Kashmir to Kangra valley to seek sanctury in the courts of the Rajas of Kangra Hill States. It is very likely that Pandit Seu was one of them". Even now, as witnessed during the research on the subject, it has been found that there are a number of families of Kashmiri Brahmins, particularly Rainas, who have settled in Haripur Guler as well as in some villages in Tehsil Palampur. The family's origin has been confirmed repeatedly through their initials on various paintings done by Pandit Seu and two of his renowned painter sons Manak (Mana) and Nainsukh (Nana) who mostly impress their name prefixed with 'Pandit' and suffixed with 'Raina' or 'Rajanaka'.

Pandit Seu Raina founded and introduced the "pre-Kangra" style in Guier under the princely patronage of Raja Dulip Singh. The style richly vibrated with an amalgam of Pahari folk and Kashmiri Pala Style. The static attitude of forms, the solidity and I decorative brilliance of colours, which imparted the tribal passion, energy, vehemence and depth of thoughtfulness in the paintings. These qualities are basically the elements of Kashmir School which are primarily responsible for the powerful sprouting of Basohli, and which, it seems, Pandit Seu and his two genius sons, Manak and Nainsukh, inculcated under the Patronage of Basohli Raja. As recorded, the most regular and frequent movement of Pandit Seu and his sons between Basohli and Guler do indicate that the father and sons must have been working simultaneously in Basohh and Guier, as the two centres are very near to each other. Besides, the interaction of influences must have worked through the past centuries, because the town has been an important stoppage on the trade route between Kashmir and Punjab and rest of India; and also through Raja Amrit Pal (1757-1776) who was a reputed lover of art and culture.

The early quarter of twentieth century regenerated the discovery of these movements. particularly Basohli paintings which have become much sought after and fabulously priced pieces of art. Incidentally, it was by sheer chance that a sizeable collection of Basohh came as a valued share to our State.

In fact, with Pandit Seu's entry into Raja Dulip Singh's atelier a complete change took place in the outlook of the workshop and brought into practice the style popularly known as "Pre-Kangra Kalani". Later on, the style seems to have spread effectively to other states, but it was most effectively pursued in Culer, Basholi and Jammu. Subject wise, Pandit Seu seemed to have invested his genius in portraitures, which could successfully maintain the pictorial qualities of vertical projection and attainment of dimensions by juxtaposition and interspersing of forms and surfaces over his canvas. Some of his highly technical and dexterous portrait studies are luckily salvaged and preserved in various museums and collections. Notable of them are the portrait sketches of his two sons Manak and Nainsukh the famous standard bearers of the movement. While he was in the employ of Raja Duhp Singh of Guler, Pandit Seu had done some of the masterly portrait studies superimposed with highly sensitive and linear brushwork; such as Mian Gopal Singh of Guler playing chess (Chandigarh Museum), formerly in the collection of Guler Darbar; "A Seated Courtier" (Victoria and Albert Museum London); "Raja Bishan Singh of Guler" (in the National Museum, New Delhi) and again 'Raja Bishan Singh', presently in the collection of late Sir Cowasji Jahangir, Bombay, the renowned patron of the modem Indian Art movements. Besides, the portrait of 'Raja Bikram Singh of Guler' ' performing pooja, and a 'Battle Scene" (Chandigarh Museum), the "Dancing Darveshes" (in Lahore Museum). All these are the subjects of a deeper study and appreciation for aesthetics. The frozen attitudes of hands, the solidity and formality of the figures and the division of the picture spaces- all these qualities, as already mentioned, are the qualities and basic elements of Kashmir School.

The three generations of Seu Raina spearheaded the fusion of Basohli and Baroque to the final flowering of the new movement that culminated in Kangra School. This transformation was the work of a single family of influential artists who originated from Kashmir The family worked at several hill centres. Guier is the centre for this technical development where the family of Pandit Seu settled in its initial stage. Seu's son Nainsukh is the best known and the most 'irmovative". He was employed by Raja Balwant Singh of fasrota (1724-1763). After Balwant Singh's death in 1763, Nainsukh moved to Basholi where his elder brother Manaku was working and was practising and propagating the new style. One of Nainsukh's sons was working in the court of Raj Singh (1764-1794) the ruler of Chamba.

The ultimate blooming of the Kangra style under the patronage of Raja Sansar Chand (1775-1823) was piloted by the third generation of Pandit Seu's dynasty. It was here that the lyrical Guler style reached a high point in the Love themes of Kangra Kalam. This subject and theme were from the love poems from the Rasikapriya of Keshav Das, the court poet of Raja Madhukar Shah (1580-1601) of Central India. The Nayak and Nayika in the Rasikapriya are Krishna and Radha, the ideal love symbols of God and soul. "Geet Govinda" series and 'Bhagwat Purana" also were the themes of this movement.

Geet-Govinda of the Vashnavite poet jaideva has achieved its passionate excellence through the master pieces created by the renowned painter Manaku, the eldest son of Pandit Seu. Poet Jaideva was the court-poet of King Lakshmana Sena of Bengal where from the Pala-Sena movement of the Gupta's laid a marked influence on Kashmir SchoolBesides, as typical of the nature of an artist, Manaku was inspired by the poet's weaving into his songs an eroticism of fascinating sensuous imageries which make the poems throb with passion and above all the word-music which flows like a murmuring brook gushing in a verdant forest. The rich imageries, the pen-pictures of landscape and the treatment of various states of love became a treasure and a rich tapestry for artist to draw upon. The artist's technical excellence, aesthetic sensitivity and emotional vibrations were idealised through the expression of his lyrical drawings, throbbing colours and quiet landscape locales. Some examples of the most romantic compositions of jaidev and their subsequent emotionally charged transformation by Manaku are worthy of high contemplation : "Oh spouse of the cowherd, caressing passionately her swelling breasts, proceeds to sing the Panchama Raga. "It is a moonlight night almost at daybreak. Birds are still roosting on the trees. Krishna stands caressing the Gopi (Radha) while the earliest pink specks of the morn have touched the distant peaks across the meadow. Krishana says :" The hair is disarranged by the tossing of tresses, their cheeks bear drops of perspiration, the lustre of her red lips is diinmed, the glory of her swelling breasts defeat the lustre of the pearl necklace, she is hiding now her breasts and her privacy with her hands. She is looking at me bashfully and though disarranged, is spreading the light of love." Manaku's rendering - It is a lush green composition of undulating meadow skirted by a brook and overshadowed by a grove under which she (Radha) is poised in helpless nude condition besides Krishna. The excellence of mastery over human anatomy coupled with delicacy of body undulations and ebb-and-flow of curvatures is the last word that Manaku has simplified and translated through the simplicity of form.

The two sets.of Geet-Govinda by Manaku- One painted in Basholi Kalam (1730) and the other in Kangra style- seemed to have raged into controversy in the columns of modem art criticism. It was finally resolved that Manaku, while in the employ of the Basholi Court in early eighteenth century, painted the Basholi set under that influence. This set was in the collection of Lahore Museum which I studied in 1946-47. The second set of Geet-Govinda painted in Kangra style represents the most exalted and final stages of sophistication which Manaku achieved through his experimentation with his techniques and observations. The throbbing and sumptuous colour, controlled but expressive draughtsmanship and the lively set-up of the landscape had established the unique standard for Manaku's compositions. These paintings are supposed to have been painted by Manaku in Guler period of 1760-1770. At some later time this set sppears to have reached the court of Maharaja Samsar Chand of Kangra and later to Tehri Garhwal as the dowry of the two daughters of Sansar Chand who were married into Tehri Garhwal family. It was simply the genius of Manaku who could establish the Basohli Kalam and then evolve through it Kangra Kalam wherein he displayed all the aesthetic sensitivities and sensibilities.

Another controversy erupted between the well known art historian Karl Khandalvala and the researcher of Pahari movement Mr. M. S. Randhava; the former claiming that the name Manaku of the Sanskrit verse appearing in the reverse side of the Basholi Geet-Govinda collection, was actually the name of the noble lady and not of the artist who is supposed to have painted the collection. Mr. Khandalavala's plea was that the name does not appear as Manak but as Manaku sounding it to be a female name. However, the controvesy was settled by late Dr. Raghuvira, the well-known Sanskrit Scholar, who translated and interpreted the two identical colophons appearing on both the BashOli and Kangra styles. The Sanskrit colophon appears as given below :

Dr. Raghuvira analyses the two last lines in the following manner : Vyarcayad = caused to be composed; aja bhakta = the devotee of Aja (the unhorn, Vishnu); Manaku = through Manaku; Chitrakartra = the artist; Vicitram = characterised by; Lalita = a delicate; Lipi = brush; Geet-Govindacitram = the painting of Geet-Govinda.

He translates the whole couplet thus; 'In the Vikrama year corresponding to the moon, the mountains, the gems and the sages, viz. V. S. 1787 and 1730 A. D. a devotee of Aja, caused this painting of the Geet-Govinda, characterized by a delicate brush, to be painted by Manaku, the artist". He adds further the literal meaning of the whole verse thus: "In the year 1787 VS (1730 AD), Malini, noted for her qualities of discrimination and judgment, and who prized her character as her principal wealth, who was a devotee of the Immortal One (Vishnu), had a pictorial version of Geet-Govinda in beautiful and varied script composed by the painter Manaku". He clarifies, further, that 'Manak' or 'Manaku' is a male name in the hills, and is never used as a female name. The female name is 'Manako', 'Gulabo' and so on. While pointing to the grammatic principal and the gender of its Agent, Gopi Krishna Kanoria, scholar and aesthete, clears the confusion in an easy manner, 'Manaku', the principal and its agent 'Chitrakartra' is enough to establish the masculinity of the painter.

Manak's younger brother Nainsukh took his service with Raja Balwant Singh of Jammu as well. His entry into the court of Jammu changed the entire mood of the tradition. Identically like his brother he had enough to offer to the existing traditions of Jammu Kalam. Observes W. G. Archer, "within this local tradition (of Jammu Kalam) which reaches its height in the portrait of Brij Raj Dev, Nainsukh of Jasrota appears as a sudden mysterious intruder'. "Intruder" in the sense that he introduced and prevailed upon the situations by introducing his strong and well organised notions about the pictorial values over which he had a masterly grip and command. His colour schemes and themes were subservient to the Organisation of form and the dimensional planes. In short, he could be put in the category of formalists and abstractionists who use natural forms for pictorial organisations. He could be aptly titled as Picasso and Mondrian of the Pahari movement. His is the marked feeling for geometric structure, strong colou'r and vitalistic line. His whole approach is architectural. His pictures are a series of receding and forwarding planes and thus nothing else could be an ideal contribution to the simple flatness of the local style. Compared to his elder brother Manak, who could be called poetic and romantic, Nainsukh was an aesthete and fundamental. A typical example of his planned picturisation is his well known painting of Raja Balwant Singh listening to music. It is a well planned canvas composed with horizontal and vertical divisions of the background and the palace architecture, within which the Raja and the musicians are mere decorations of the broader planning and composition. Another similar masterpiece is "Raja Balwant Singh of Jammu inspecting a horse".

In earlier career of his Guler days and later on in Jammu his aesthetic and formalistic principles dominated the local tradition, while his occasional short visits, under the patronage of Raja Amrit Pal of Basholi, created a great change in later Basholi period. Nainshkh seemed to be a dominating influence in Jasrota also, and being so effective in Basholi, Guler, Jammu and Chambha.

The Emergence of Chamba School

In the later part of eighteenth century the Samba principality seemed to have been gaining an edge over the neighbouring Basholi. This was the period when Basholi became subservient to Chamba politically as well as economically. This prosperity seemed to be the reason for cultural and artistic rejuvenation, particularly in the fields of architecture and painting. Nainsukh moved from Guler to Jammu and from Jammu to the court of Raja Amrit Pal of Basholi where he laid deep influence of his own style of miniaturist delicacy. Later he very ideally created a style that was a subtle fusion of delicate silhouettes and Pahari colour tones. Thus the element of Aesthetic Romanticism was brought into the Bashoh primitive style. The style took firm roots in Basholi quickly and very swiftly. The door wings made in Kangra style were brought by Raja Raj Singh to Chamba when he sacked Basholi palace in 1782.

It is evidenced that Nainsukh would visit Chamba court occasionally, and later on, his sons Ranjha and Nikka were responsible for the artistic prosperity and the establishment of Chamba Kalam, it being an ideal fusion of Kangra-Guier miniaturism, Pahari purity of colour-tones and element of primitive vigour of Basholi forms. The well-known series of "Rukmini Haran" are a typical example of Chamba School studies.

The subjugation of and predominance over Basholi seems to have been responsible for the emergence of Chamba style as most of the sons of NainsukhRanjha, Nikka and Godhu led the activity of the atelier of Raja Raj Singh of Chamba. Nikka, the third son of Nainsukh, is known to have founded the style in Chamba court but was later on joined by Ranjha (fourth son) and Godhu the second son. AR the sons, Kama, Godhu, Nikka and Ranjha were, along with their father, the Guleria painters and were for sometime settled there wherefore they spread their artistic tentacles over Basholi and Chamba, finally settling in Chamba. This activity was further strengthened by the effective contribution of Harku and Chaioo, the two sons (third generation) of Nikka.

Ranjha, the most talented one, remained in the court of Raj Singh from 1772-94. These were the years when well-known "Anirudh Usha" series were painted by him. Intermittently, Ranjha seemed to have been paying commissioned visits to Bashoh where, in the service of Raja Amrit Pal he painted the "Nala-Damayanti" series. This series, though painted in Basholi was the typical Chamba style, thus having laid its strong influence on Basholi tradition. In this series there are visibly strong influences of Chamban architectural forms.

Ranjha the fourth son of Nainsuk, was most dynamic in maintaining relations from Chainba with Guler and Basholi as well. He seems to have been occasionally attending these courts, particularly the court of Raja Bhup Singh of Guler.

A significant collection of Ramayana series was painted by Ranjha during the reign of Raja Ghupendra Pal (1816) of Basholi. The basic drawings of the series were got made by Ranjha from another Kashmiri artist (not in the family) named Sudarshan. This gives insight into the methodology and process that must have been going on into the workshops of artists, where there used to be a professional division between masterdrawer and the painter. Such a tradition of division seems to have been lingering on in the house of the last-known painter, Narayan joo Kachru "Mooratgarh" of Srinagar. The division of work was between him and his daughter. She would prepare the drawings and father would complete the miniatures with colours and the brushwork details.

Ranjha's son Gursahai (fourth generation and grandson of Nainsukh) proved a greater genius in drawing and draughtsmanship. Super-sensitive, erotic and highly passionate themes were the main subjects of his paintings. His great studies in appreciation of human anatomical form and its highly interpretative formation could have been the work of a genius only. He thus composed highly sensitive compositions of nude studies. The "Kokashastra" series also remained one of the chief products of his collections.

Atra, the son of Nikka worked in the court of Raja Raj Singh of Chamba. The inscription over one of his paintings reads the names of Nikka, Ranjha (Ram Dayal), Chajju, Harku (Nikka's son) and Saudagar (the fifth generation and grandson of Nikka) besides himself, mentioning all being in the atelier of Raja Raj Singh of Chamba.

Ram Dayal, the grandson of Nainsukh worked in the court of Bijai Sen of Mandi. Kiru - five generations away remained in the court of Patiala. Nainsukh's elder brother Manaku had two sons. namely Khushala and Fattu. The whole family worked in the court of Raja Goverdhan Chand of Guler till his death in 1773. They continued with Raja Prakash Chand till 1785, but intermittently leading their projects in other centres like Basholi and Chamba. The occurrence of financial crisis in the court of Guler led to the migration of Raia Sansar Chand's court at Kangra. Khushala became the chief painter in the Kangra court and painted a Geet-Govinda series for Maharaj Sansar Chand.

Chetu the great grandson of Khushala (fifth generation) and Sultanu the grandson of Nainsukh, both were the court artists of Raja Shamsher Singh (1826). Chetu's paintings reached the court of Garhwal, but there are indications to his physical presence in the court of Sudarshan Shah of Tehri Garhwal, where he established the Garhwal School of Pahari movement.

The other important centres of Pahari movement led and established were Tira Sujanpur, Mandis Patiala (a non Himachal centre) and Kulu. The Kulu style is considered to be an ideal amalgam of folk and Kashmir style. Some of the fourth generation Rainas migrated to Kulu in the second decade of the eighteenth century.

Surprisingly, the six generations of Pandit Seu Raina produced about forty-six children, and all of them artists who penetrated their genius very deep into the mileu of all Himachal principalities, thus embedding the whole treasure-accumulation of four thousand years into their new home of outer Himalayas. It needs yet another treatise to keep their track in all the courts and cultural centres of the region.

The essence of cultural treasure of Himachal Pahari is the decoctant of human experience accumulated through the constant in-flux and out-flux of human migrations and re-migration along with the shores of Mediterranean, the Tigris Euphratic waters and the settlements which thrived along the shores of Ganga, Yamuna, Sindhu and Saraswati.

It has been time-and-again that this forward human leap had to be preceded by a mighty exodus of civilised races. Thus, the history in this respect, has been repeating itself; and I think to complete the circle the history has again pushed us on the path of exodus to take once again a great leap forward as we did in the recent past.

I think, this is the only call (or should I call it NAAD) of the hour for those who migrated due to the brutal convulsions of our History.

References

1. Wushkar Baroque : Wushkar, a well known village in Baramulla (Kashmir) on the bank of Vitasta (Kashmiri name of jehlam river) where famous Buddhist Viharas had a massive facade of terracotta creations depicting Bhudha's life. The style, now internationally known after the name of the village, is the culmination of Gandhara-Mathura style rendered with sensitive details (linear) of expression and decoration.

2. The name Shivji Raina is even now a common name amongst Kashmiri Pandits. Phonologically, in Himachal Pahari Parlance 'Shiv' has changed into 'Seu'.

3. The pilgrimage registers kept by Pandas at Haridwar, Kurukhestra and Pehowa do confirm and state as "Pandit Seu Raina of Guler"

4. First discoverers W. G. Archer and Percy Brown.

5. Though in most inhospitable conditions, this biggest collection now lies in the Dogra art Gallery of Jammu. Before its acquisition, this valuable collection remained as the personal property of one Pahda Kunj Lal, a descendent of the royal physicians of Basholi Rajas. It was in 1956 that a devastating fire in Basholi destroyed property of Hakim Pahda Kunj Lal and thus he was compelled by circumstances to present the sizeable collection to the then Chief Minister of the State, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed who came to visit the town. This valued collection was loaned by the Chief Minister for an exhibition of Festival of Kashmir, of which myself and reputed Kashmir poet late Pandit Dinanath 'Nadim' were the organisers. I felt that this treasure should remain a national treasure rather that a personal property. Pandit 'Nadim' and myself posed the problem to the then Education Minister late Mr. G. M. Sadiq who sorted out the matter with the Chief Minister and thus this valuable collection became the national property.

6. Chandigarh Museum and Indian Museum Calcutta.

7. "Arts of India"- Victoria and Albert Museum.

8. This led to the foundation of Chamba Scho6l.

9. God is achieved not through austerities but through love.

10. "Notes on Pahari Painting" by Gopi Krishna Kanoria (Rupa Lekha, AIFACS)

11. Mannakuchitrakarta should be taken as one word in which Manaku is the principal and is its agent denoting the gender. Its feminine would be chitrakartee

12. Collection of Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

13. Now the door-wings are in the collection of Bohri Singh Museum, Chamba.

14. 1764-94, rule of Raja Raj Singh of Chamba.

15. Bohri Singh Museum, Chamba.

16. Dr. Karan Singh Collection.

17. Dr. Karan Singh Collection. Collection: Bohri Singh Museum of Chamba and the Punjab Museum, Chandigarh.

18. "Kangra-Artists", Art and Letters, 1995, Vol. YXIX, No. I.

19. Collection: Bharat Kala Bhawan, Banaras. 'The Artist of the so-called Ranjha-Ramayana drawings" J. R. A. S., vol. XXI, No. 9/3-4,1979.

20. In Kashmir, Papier-Mache professionals are still divided as khuhunmore and Nakash. The original leykhan = leykhun in Kashmiri in which by practice becomes silent. So leykhan (Hindi) > leykhun > suhun

21. "N. G. Mehta collection" by Khandalwala.

22. The "Ramayana Series", "The rape of Yadav women", the "Birth of Krishna" from Bhagwat folio and "Rukmini Parinaya"- all in the collection of Chandigarh Museum.

23. Godhu the second son of Nainsukh along with uncles Fatu and Khushala, took the Kangra influence in the principality.

24. Ram Dayal the great grandson of Nainsukh worked in the court of Raja Bijay Singh (1851) of Mandi.

25. The famous Shangri Ramayana Series have been painted in this Kalam.

26. For the profound in-depth and crisscross forward movement of human culture I refer to great and classic book titled 'The Martyrdom of Man' authored by Winwood Read, and first published a century ago.

How Kashmiri Pandits Preserved Painting

By P.N. Kachroo

The Kashmiri painters, in their heyday of estab lished movements had chiseled and garnished a style based on the traditions of Harvan formalism and Baroque of Wushkar school and contented with their philosophic thought. The chromatically decorative element composed with spatially organised figurative symbols constituted the great Kashmir murals, of which the majestic but lingering appearance still stands in the monasteries of Alchi in Ladakh, waiting pathetically for its demise. Further, the style was subtly and sensitively ornamented with the linear sensibilities observed in Mathura and Pala schools while their seasonal sojourns and pilgrimages.

Hordes of such aesthetes and creators went out in the company of eminent and propagating Kashmiri scholars under numerous leading painters like Hasuraj and lead their artistic movement as far as into Tibet, while contributing to the establishment of themes of Buddhistic Mahayana-Vajrayana in Central Asian regions.

The barbaric and devastative onslaught of Islamic iconoclasm, ushered in early thirteenth century, which vandalized, ignited and razed to ground all the monumental edifices and temples of national sanctity along with the invaluable and creative wall frescoes, murals and gold gilt paintings. The examples are still lingering over the mud walls of monasteries of Alchi. Consequent to this the Kashmiri painter suffered a deep cultural shock and a grievous starvation for means and methods of expression. But, as always like a typical Pandit he not only survived the shock but came up with an alternative equipment that did not only bring forth but strengthened and energized the Kashmir miniaturist movement. Thus the base for expression shifted from monumental areas and structures to portable areas of Burjapatras and home made papers. This altnerative means for expression did not only safeguard the continuance of his creativity secretly, but also made it easy for him to carry his masterpieces in case of his migration to seek shelter for his life. This physical fanning out widened the field of diffusion for the Kashmir style, leaving behind the pieces of master--expression not only in neighbouring Himachal principalities but in places of pilgrimage like Kurukshetra, Vrindavan, Haridwar and in as far away places as Sangam and Varanasi.

During the transitory periods of peace in the Valley the customary pilgrimages, particularly in winters, had taken the shape of an intensified yatra of Sthanapatis (Thanapti) from numerous religio-cultural centers like Jeshtheswara, Martand (Matan) and Vijeyashwra (Vejabror). This would compensate their prevailing penury through annual visitations to their Jajmans living in various Indian principalities. These hordes of migratory Brahmins were joined by numerous painters, calligraphers and scribes who, in their search for economic survival, would move from village to village, particularly in neighbouring outer Himalayas and Punjab. The numerous groups of scribes and painters would drop themselves in a nearby Sarai of a town at its outskirts and then fan out in the alleys of township and would hawk and call Muratgarh! Chitragarh! Likhari! In later periods of Indian Muslim rule their calls changed into Mussavir, Katib, Mussavir-mi-Katib, the painter and scribe together.

In absence of printing technology the profession of a scribe and book illuminator proved to be an indispensable profession that kept the starving Brahmin and painter wedded to his staunch faith and philosopy. He would hawk in the various lanes of Indian settlements and would transcribe and illumine the various tattering Pothis and manuscripts. It has become customary for every household to provide these pundits free quantities of oil, besides their wages, so that they could finish their job by burning the midnight oil. The wandering Pandits would pack up their bundles the moment their job would finish, and would move to another Sarai and seek out their job for transcription and illumination. At the advent of spring time, in case the situation permitted, these groups would return to the Valley to spend their summer time with their kin and families.

Various collectors and research scholars, particularly Swiss, German and American teams and organisations have collected a sizable number of such manuscripts and Pothis from various Indian townships, scribed and painted by these wandering pilgrims of culture who have fanned out the aesthetic elements of Kashmir school to wider areas of the subcontinent. Recently, one of the most creative collections of a high aesthetic order lying now in the Museum Reitburg, Zurich from Alice Boner collection of Switzerland, has been published by these authorities. This is one of the finest collections of Kashmir school, depicting the various forms of Shakti as interpreted through the creative forms of Kashmir Miniaturist movement.