Upender Ambardar

Upender Ambardar

Upender Ambardar is a well-known Researcher and an M.A. in Kashmiri Literature from Kashmir University. He specialises in Social history and Culural traditions of Kashmiri Pandits. Presently, he is serving as Programme-Executive, All India Radio.

Featured Collections

The Winter Rituals of Kashmiri Pandits -The Legacies of Past

By Upender Ambardar

THE hallowed land of Kashmir is blessed with divinity in enormousness. The rituals, customs, traditions and celebration of sacred days are cultural, social and religious expressions of great cultural mosaic of Kashmir. Mysticism, mythology, spiritual thought and socio-cultural history are formidable ingredients of our festivals, rituals and customs. The local shades and native identities inherent in them not only connect us with the past but also help in the socio-historical reconstruction of antiquity. They land hope, grace, zest, variety and grandeur both to an individual and the society. The prominent winter rituals of Kashmir are - Gada Bata, Majhor Tahar, Chari Oakdoh, Lavsi Chodah, Kichdi Amavasya, Makar Sankranti (Shishar Sankrat) and Shishur etc. They represent the community's religio-cultural pride as they give us social, psychological religious, cultural and emotional compactness. Moreover, their origin and roots can be traced to the progenitors and forebears of the community centuries back.

Our unbending faith in them reminds us not to forget the ancient land and rich civilisation of the past to which we belong.

Gada Bata:

'Gada Bata' stands out conspicuously as an imposing and time honoured winter ritual of Kashmiri Pandits. The ritual has survived even in our forced exile despite a brush with the modernity. It is celebrated in the month of December during the dark fortnight of Posh locally known as 'Poh Gutpach' either on Tuesday or Saturday. As per a religious belief, every house has a presiding and governing deity, reverently remembered as 'Ghar Divta' or 'Dayat Raza' by Kashmiri Pandits. The house is believed to remain under the benevolent and protective surveillance of 'Dayat Raza' everytime. A religiously pious house is thought to have auspicious and positive dividends. The believers share a firm conviction that positive and spiritual resonance generated due to the presence of presiding deity of the house drives away bad omens, evil spirits, acrimonious feelings and negative retardants if existing in the house. His indivisible presence also guarantees wellness, harmony and stability of kinship among the inmates of the house.

It also testifies a centuries old notion that elements of spiritualism, religiousness coexist alongwith materialism in a harmonious blend in the houses of Kashmiri Pandits. The ritual of 'Gada Bata' is an eagerly awaited occasion in every Kashmiri Pandit house even now. On any selected Tuesday or Saturday of Posh Krishna Paksh, the divine patron of the house called 'Ghar Divta or Dayat Raza' is propitiated by an offering of fish dish and rice. On the designated day, the kitchen is cleansed and the needed utensils are thoroughly washed. The fish to be cooked are spotlessly cleaned and cut into whole girth pieces. The entire volume of used water along with the scrubal fish scales, fins, discarded fish inners are retained and thrown off only when the fish and rice offering is made to the 'Dayat Raza'. The fish are cooked in combination with nadru, reddish or Kadum (Knolkol) as per the family's ritual or 'reath'. It is followed by invocational pooja of rice and fish dish. Afterwards, rice and cooked fish pieces in the sequential order of head, middle and tail portions are kept either in fresh earthen plates (toke) or on grass woven circular base (Aer) called 'chret' or in a thali as per the family 'reeth'. They are now placed on the clay smeared floor of the upper storey room of the house called 'Kani or pbraer-Kani' A washed uncooked and ..dressed fish is also kept on a separate grass woven ring called 'chret' adjacent to the above offering. An oil lit earthen lamp (choang), a tumbler filled with water and a tooth pick (optional) are also kept near the rice and fish offering. As per the family custom, the offering is either kept underneath a willow basket called 'Kranjul' or left uncovered. The said room is then left undisturbed and unattended during the night. The following morning, the families in accordance with their 'reeth' either put the rice and fish dish offering on the house roof to be fed upon by the birds or share the consecrated food-offering as 'naveed' by the family members. As per belief, the scattering of rice grains and sight of fish bones kept aside is indicative of the acceptance of the offering by the 'Ghar Divta'.

Every care is taken by the family to ensure the religious purity during the celebration of this ritual as any deviation or flawed observance invites 'Ghar Divta's' annoyance and anger. The oral narratives and family lores are full of the wrath inviting incidents. Recounting a happening of such nature at her Habbakadal residence as heard from her elders Smt Aneeta Tikoo revealed "Once a delay in performing the 'Gada Bata' ritual resulted in disquietening noise coming-out from the 'Thoker Kuth' for several nights. It was taken as displeasure and annoyance of the 'Ghar Divta'. Immediate celebration of the ritual astonishingly put an end to the mysterious noise."

Recollecting another incident of the yore, she elaborated "once an elderly lady Smt. Visherded received a mysterious bash from an invisible force in the house. It was taken as an indication of some wrong doing during the observing of ritual. Afterwards, the ritualistic offering made once again put the things right." Narrating one more unusual happening of 1970s, wherein a lady in the neighbourhood the fried inner parts of fish before the customary offering was made to presiding deity of the house. It resulted in the hurt caused to the said lady by unexpected collapsing of the kitchen wall during the course of cooking, which was an indication of 'Ghar Divtas' anger and ire".

Sharing a personal experience in the existence of 'Ghar Divta', Sh Susheel Hakim, an erstwhile resident of Karan Nagar, Srinagar, also recounted "for several days in the year 1980, I would feel enormous and mysterious heaviness pounding my body in my bed during night in wakeful state following the opening of my room door on its own. Astonishingly, the mysterious feeling of pounding vanished after the well-known mystic of Karan Nagar Kashi Bub, fondly known as Kashi mout, who used to frequent our home advised me to make an offering of rice and fish to 'Ghar Divta'. Narrating one more related incident of the same year, Sh. Susheel Hakim divulged "one of our tenants Sh. Anil Kachroo, a student those days would observe the unoccupied bed in his room getting weighed down by a mysterious and invisible force during night, which would precede the automatic opening of the room door. The bed would regain its original form after a brief spell, indicating that a divine figure had rested for a while on the bed".

Sh. Roshan Lal Zadoo, presently at Bhagwati Nagar Jammu also shared a similar incident that his father late Sh. Dina Nath Zadoo had noticed a divine figure in white robes descending the staircase of his home at Nowgam Kuthar, Anantnag.

Manjhor Tahar:

One more important winter ritual is that of 'Majhor Tahar', which is celebrated on Magh Purnima, locally known as Manjhor Punim. The ritual comes in the months of November-December. It is a thanks giving ritual towards the all pervading Almighty God, who is the source of our sustenance and subsistence. It is symbolic of His generosity and benevolence bestowed upon us in the form of bountiful cultivated crops. On the day of Magh Purnima, yellow coloured rice (Tahar) and potatoes and 'Kadum' (Knolkol) spiced with red chillies are cooked during night.

After the customary pooja, the offering - the 'Tahar' and the cooked vegetable dish known as 'chout' is kept on the roof top during the night itself. Afterwards, the remaining portion of the food is taken as 'prasad' by all the family members. In certain places, the ritual is regarded to signify the fertility of the soil. The believers offer the oblation of 'Tahar' and cooked vegetable dishes to the deity of crops in their crop fields. The ritual of 'Manjhor Tahar' is celebrated to invoke the deity of crops and soil fertility for ensuring allround welfare and prosperity in the form of bountiful crops. The ritual is also supposed to ward off the damaging influences, which may affect the crop production. The ritual also enforces the intimate and fruitful relationship between man and the forces of nature, which are believed to shower grace, mercy and blessings in the form of different varieties of crops cultivated by us. The food or crop represents the physical matter, which guarantees the sustenance, nourishment and household protection.

The yellow colour of 'Tahar' is a mystical interpretation of auspiciousness, spirituality and positiveness. Yellow is regarded as a royal colour and is symbolic of the flow of sacred energy, which is believed to activate and stimulate the surroundings. The yellow colour of 'Tahar' also denotes warmth, glow and bloom in every action connected with our life.

Chari Oakdoh:

'Manjhor Tahar' is followed by another ritual know as 'Chari Oakdoh', which is celebrated on Posh Krishna Paksh Pratipadha, locally known as 'Poh Gutpach Oakdoh'. The ritual involves the cooking of rice and moong dal. About seven or nine small rectangular stones collected from the river or streams are seated on grass woven rings called 'Arie'. These are symbolic of the 'Mother Cult' or 'Shakti Pooja' and represent 'Matrakas' or little Divine. Mothers.' 'Matrakas' are known by the names of Brahmni, Mahesvari, Kumari, Vaishnavi, Varahi, Narasimhi and Aindri or Indrani.

They are the 'Shaktis' of Brahma, Isvara, Kumar or Skanda, Visnu, Varaha, Narasimha and Indra. According to Tantarshastra, Brahmini represents the primordial nada, which is the unmanifest sound denoting the origin of all the creations. It resembles the Divine energy as represented by the 'Pranav' or 'Om'. In the ritualistic invocation of the 'Matrakas', offering of rice and dal mixed together are placed before the seven or nine 'Matrakas' represented by small rectangular stones. It also involves the applying of tilak to all the idealised images of 'Matrakas'. Afterwards the family members take the 'naveed'. The 'Chari Oakdoh' is also known as the ritual of 'Matraka Pooja'.

Lavsie Chodah:

One day ahead of 'Kitchdi Amavasya' comes the little known ritual of 'Lavsie Chodah'. It is celebrated on Posh Krishna Paksh Chaturdashi. In this ritual, apart from rice, moong dal in combination with reddish is cooked.

After the traditional pooja, the offering of rice and the cuisine of dal and reddish is kept on the roof top. The consecrated portion is taken as 'naveed' by the house inmates.

The ritual of 'Lavsa Chodah' has presently lost much of the original ritualistic fervour and has receded in significance. It needs to be taken back to its pristine glory.

All the community rituals need to be celebrated with unquestioned faith as besides spreading cheer and mirth, they have an impacting role in shaping our lives.

Khaechimavas or Khichdi

Amavasya is an ancient winter ritual of Kashmiri Pandits. It is celebrated on Posh Krishna Paksh Amvasaya (Poh Ghata Pach Mavas) with unshakeable faith by Kashmiri Pandits. Khaechimavas besides being an integral part of our religio-cultural life also encompasses the mythologized history of Kashmir.

Further, it authenticates and affirms the historicity of Yakshas, the ancient aboriginal tribe of Kashmir, who dwelled in the upper mountainous region of the Himalayan ranges extending from the present day Uttranchal, Himachal Pradesh to Kashmir. The Hindu scriptures have elevated Yakshas to the status of demigods along with Gandharvas (the celestian musicians), Kinnaras (the divine choristers), Kiraats and Rakshas.

The influence of Shaivism on the ritual of Khichdi Amavasya is clearly visible.Yakshas were also ardent worshippers of Lord Shiva, the most adored and revered God of Kashmiri Pandits.

The Yakshapati Lord Kubera is regarded as an intimate friend of Lord Shiva. Lord Kubera, known as the Lord of wealth, is said to be the son of sage Visravas and grandson of the sage Pulastya besides being the half brother of the demon king, Ravana. As per the Hindu mythology, Lord Kubera resides in the mythological city of Alkapuri, which is said to be situated on one of the spurs of the Mount Meru in the exalted Himalayas. Incidentally, Mount Meru, which is believed to be densely forested with the divine 'Kalpavraksha' trees is said to be the abode of Lord Shiva also. Alkapuri is also known by the names of Vasudhara, Vasusathli andPrabha. As per the Hindu epics of Ramayana and Mahabharat, Lord Kuber had his sway on the city of Lanka before he was ousted from there by his half brother, the demon king Ravana. He was also the proud owner of the celestial aerial chariot 'Pushpak Viman', which was later-on snatched away from him by the demon king Ravana. The city of Lanka is believed to have been built of gold by the divine architect Vishwakarma for the residence of Lord Kubera.

Yakshi also known by the alternative names of Charvi and Kauveri, the spouse of Lord Kubera is said to be the daughter of Danav Mura. She is believed to serve Goddess Durga as one of the attendants. Manigriva (also known as Varnkavi) andNalkubera (also called as Mayuraja), are Lord Kubera's sons, whileas Menakshi is his daughter. Lord Kubera, the King of Yakshas is also known as Dhanpati (the lord of wealth), Nar-raja (the King of men), Rajraja (the King of Kings),Ichchhavasu (one who gets immense wealth at his own wish and will),Ratangarbha (one who possesses plenty of jewels and diamonds) and also asRakshasendra (the chief of demons). He is also known as the presiding deity of the northern side of the universe and the house. Hindu mythology describes Kuber to have a white complexion, a deformed body with three legs and only eight teeth. Further, he is regarded not only as the lord of gold but also of silver, jewels, diamonds and all other kinds of precious stones. He is also known as the protector of the business class of the society.

In the mythological depictions, Lord Kuber is shown as seated on the shoulders of a man or riding a carriage pulled by men. Sometimes an elephant or a ram (an uncastrated male sheep) are also shown as his mounts. The subjects and devotees of Lord Kuber are called as Yaksh and they are believed to possess supernatural powers. They can change their shape and form at will. They are regarded to be full of kindness, compassion and benevolence.

According to Kalhan's Raj Tarangni, Yakshas resided on the mighty mountain ranges of Kashmir. They would descend to the plains during the winter season, where the Naga inhabitants would extend the hospitality to them by offering the delectable cuisine of Khichdi. The Yakshas are believed to be historical reality down the ages as innumerable villages and temples have been dedicated to them. They exist in vast stretches of land right from the present day states of Uttranchal, Himachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir. In the capital city of Shimla in Himachal Pradesh, there is a famous Hanuman temple on the adjacent Jakhu hill. It is believed that thousands of years back Yaksha sage performed austerities and penance there. Lord Hanuman is said to have made a brief stopover at the Jakhu hill during his search for 'Sanjeevani Bhooti' for Lakshman. The sage Yaksha latter-on built a temple on the hill in honour of Lord Hanuman. In Rohru and Arki tehsil of Shimla district, two villages dedicated to Yakshas are known by the names of Jakhu and Jakhol. The word Jakhol in the local dialect means 'Yakshalai' or the abode of Yaksha.

In the central part of Himachal Pradesh, there are many temples dedicated to Yakshas and Yakshanis, who are worshipped as the village deities of the natives. They are also regarded as the deities of domestic cattle. In order to ward off the evil spell and to guarantee plentiful of milk, Yakshas are propitiated by burning 'dhoop' and incense sticks in the cowsheds. Dr. M.S. Randhawa, a noted researcher writes in his book "Farmers of India" that Pischas, Yakshas andNaga tribes inhabited Kashmir in ancient times. Prof. DD Sharma, a well-known historian and researcher has identified numerous villages dedicated to Yakshas in the hilly regions of the Himalayas in his book "Himalayan Sanskriti Kae Muladar". There is a strong belief among the people in the hilly areas that affluence and fortune will come one's way if the Yaksha King Lord Kuber is propitiated and pleased. The said belief also exists in the folklore of Kashmir.

According to Prof. D.D. Sharma, the villages of Jakh, Jakhet in Karanprayag,Jakhola in Joshimath, Jakhni and Jakhoal in Chamoli, Jakhand, Jakhanyali, Jakhvadi, Jakholi, Jakhni and Jakhi in Devprayag, Jakh and Jakhol in Tehri Garhwal, Jakh, Jakhni, Jakhola and Jakhmoli in Pauri Garwal and Jakhu on Dehradun-Rajpora road not only had strong association with Yakshas but also speak volumes about their possible high concentration in these places in the ancient times. In addition to it, the entire area of Alaknanda right from Joshimath to Karanprayag is known as 'Jakh' or the area which was once occupied and dominated by Yakshas.

According to Dr. Jagdish Prasad Samval, a celebrated researcher, a temple known as 'Yakshraj' exists on a mountain top about one km. away from Narayankote on the road leading to Kedarnath. Yakshraj, Lord Kuber is the local deity of the surrounding eleven villages of the area. Likewise, there is a Yakshraj temple in Pithoragarh also, where meat offerings are made to the deity. Yakshraj is also the guardian deity of the adjacent villages. Almora also has a famous temple known as Jakhani Devi temple.

According to Prof. D.D. Sharma, Almora area has Jakhnola, Jakhnoli, Jakhani, Jakh villages, whileas Ranikhet has Jakhni, Jakh and Nainital has the village by the name of Jakh. In Jammu province also there are two villages-Jakhni (65 kms from Jammu city on way to Udhampur) and Jakhbhar (4-5 kms from Kathua on Nagari road).

In Kashmir also, the Yakshas have left their impressions behind. These have survived in the form of village names even upto the present times. The villages ofIchikote, Ichigam, Ichihama, Ichigoz and Rairyach situated in the central district of Budgam (Kashmir) might have been Yaksha settlements at certain stages of time. I have also been able to locate one more village by the name of Yachihoum, which is nestled in the foothills of forested mountain on Srinagar - Sonamarg road in Ganderbal district in Kashmir. One more village known by the name of Yachinar is situated in the southern district of Anantnag in Kashmir. According to Late Prof. Laxmidhar Kalla, a noted Sanskrit scholar of India and HoD Sanskrit, Delhi University, a village by the name of Alkapuri exists near the village Manigam in Ganderbal (Kashmir). Some scholars state that a tribe by the name of Yakshun lives in Dardistan area, which is located in north of Kashmir. They assert that the name Yakshun is a derivative from Yakshkun meaning Yakshas. A township to the west of the present day new airport near Humhama village in Budgam village locally known as Damodar Wudar is said to have been built by an ancient King of Kashmir, Damodar. Yakshas, who were adept in the construction skills are believed to have contributed help and expertise.

Yakshas have also left their imperishable imprints on the social fabric of Kashmir. They are in the form of Surnames of 'Yaksha', 'Yach' and 'Rakshas' retained by Kashmiri Pandits.

Lord Kuber is said to be the chief of both Yakshas and Rakshas. Late Sh. Dina Nath Yaksh, a noted Sanskrit scholar of Kashmir was a resident of Bulbullankar, Alikdal Srinagar upto the year 1990. About five to six Pandit families having the surname 'Yach' were residents of Rainawari (Karapora Khushki) area in Srinagar upto their migration from there in 1990. A few Pandit families with the surname'Yach' were also residents of Karfalli-Mohalla, Srinagar and Sopore township of Baramulla district. According to few Hindu scriptures 'Rakshshas' are not demons but on the contrary benefactors and defenders.

According to Kashmiri folklore, Yaksh is believed to make two and half sounds of 'Waaf' (two high pitched and one low volume sounds). The same folklore says that Yaksh dons a red cap made of gold, which is studded with jewels and diamonds. This cap known as 'Phous' is said to bestow enormous supernatural powers to Yaksh.

As per prevalent lore in Kashmir, anyone who succeeds in snatching the cap and then hides it under a mortar or a hand mill stone or a pitcher filled with water or an earthen pot full of fermented kitchen leftover vegetables called 'Saderkanz' is believed to tame Yaksh. The snatcher is given unlimited wealth if the cap is given back to Yaksh.

According to family lore of Ambardars, one of their ancestors is believed to have seized the cap of Yaksh. After the cap was returned to Yaksh, the Ambardar families were exempted from offering the oblation of Khitchdi to Yaksh on the ritual of Khitchdiamavsya. The same family lore states that once one of their ancestors, who in violation of this exemption dared to observe the ritual ofKhitchdiamavsya had his house engulfed by fire. Since that time the Ambardar families of Kashmir continue to abstain from observing the said ritual.

Observance of the Ritual:

On the evening of Khichdi Amavasya (Khaechimavas), rice mixed with turmeric powder and ungrinded moong dal is cooked. Khichdi is also prepared with meat or cheese as per the individual family's tradition. Khichdi cooked with sanctimonious purity is kept either on a fresh earthen plate (toke) seated on a hand woven circular grass base called 'aer' or in a 'thali'. Adjacent to it, a pestle (Kajvut) is also seated on a round grass base (aer) in an upright state.

During the ritualistic pooja, tilak is applied to the pestle. The pestle is a symbolic representation of Lord Kuber, the King of Yakshas. After the completion of navigational pooja, the offering of Khichdi kept in the earthen plate and seated on the grass base (aer) is placed on the court yard wall of the house. Afterwards, the consecrated potion of Khichdi is taken by the family members as 'prasad' either with uncooked reddish or Knolkhol pickle.

In some rural areas of Kashmir, Khichdi of 'mash dal' called 'Maha Khaechar' or Khichdi of black beans or 'Varimuth' is also cooked. It is prepared for the domestic cattle. This kind ofKhichdi along with a bit of honey is kept in the cowsheds, paddy storage room (daan-kuth) and on cowdung heaps. In the morning it is fed to the cows. As per belief, it not only increases the milk giving capacity of the cows but also protects them from the various ailments as the Lord Kuber is also the Lord of domestic cattle. It bears close resemblance with a practice followed in certain rural pockets of Uttranchal and Himachal, where pooja is performed in the cowsheds. The pestle kept during the ritual of Khichdi Amvasaya is symbolic representation of our steadfastness and unwavering faith for the said ritual. It is also metaphoric representation of the hilly regions where Yakshas lived in the past.

The pestle denotes the absolute formlessness of the all powerful God. On the evening of Khichdi Amavasya, a few Pandit families of Sopore township of Baramulla district make a bonfire of wood on the riverbank (Yarbal) and burn crackers. It is believed to bestow health as fire is supposed to consume all kinds of human ailments since Yakshapati, Lord Kuber is also regarded as the deity of health.

Sharing a ritual related incident of the year 1981, Sh. PN Tikoo, a retired engineer of Vijayanagar, Talab Tillo Jammu, recalled. "The residents of the newly constructed government quarters of Khannabal, Anantnag (Kashmir) were baffled by the unusual sounds of 'waaf', heard continuously during wintery nights. All the measures undertaken by the residents neither stopped the unusual sounds nor led us to the origin of sound. Astonishingly, the sounds of 'waaf' stopped the moment I made a ceremonial offering of Khichdi to Yaksh".

All the rituals need to be celebrated with fervour and faith as they give spiritual resonance to our lives.

Festivities Galore - Shivratri

By Upender Ambardar

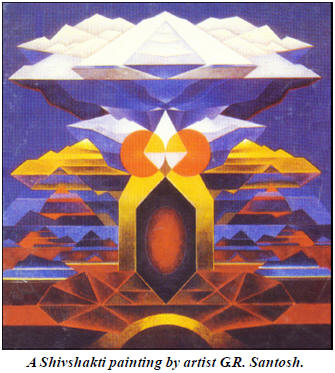

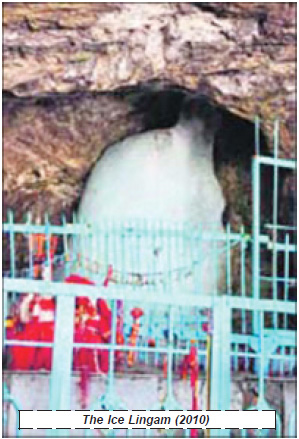

FESTIVALS and sacred days have deep roots in our socio-religious traditions. They form a significant part of our cultural heritage. Their celebrations lead to spiritual upliftment, soul purification, moral enrichment besides self-discipline. The festivals sustain our spirits, add colour, zeal, variety and zest to our existence and in the process help to keep our traditions and time tested rituals alive. Kashmir has been a seat of spiritual and cultural strength since ancient times, Kashmiri Pandits are basically Shaivites and Shaivite philosophy has attained growth and strength in the serenity of cool and calm surroundings of Kashmir. The worship of Lord Shiva and his Divine consort Parvati is an inseparable part of our tradition and culture. Shivatri, locally known as 'Hayrath', is sacred festival of Kashmiri Pandits. This ancient and auspicious festival has immense religious and cultural sanctity. It's sanctity finds a prominent reference in the sixth century Sanskrit text, 'Nilmat Puran' of Kashmir. Shivratri festival has also been highlighted in the famous philosophical work 'Shivastrotravali' of Utpal Dev, the great Shaivite philosopher of the eighth century. One of the greatest Shaivite, AbhinavGupt has also paid salutations and obeisance to Vatuk Bhairava in his famous Trika philosophical work called 'Tantraloka'. Even the renowned historian Kalhan's 'Rajtarangni' also bears an invocation to Lord Shiva at the very start of the text. The famous treatises like 'Sivadrashti' by Acharya Somananda, 'Shivstotravali' by Utpal Dev and 'Pratyabhijna Darshnam' by AbhinavGupt have contributed immensely towards the enrichment of Kashmir Shaivism. Kashmir Shaivism, also called Trika Shastra is the philosophy of triad, which comprises Shiva-the Universal consciousness, Shakti-the Divine energy and Nara-the human soul. It regards the entire creation as His manifestation, which is real and not illusion. We worship Lord Shiva in His both forms of Shiva and Shakti. Shakti for us is the Goddess Raginya, Sharika, Kali or Durga, who are the energy aspects of Lord Shiva. Worshipping Lord Shiva leads to the cosmic mother, who offers solace, protection and divine grace to one and all.

Accordingly, the ultimate Truth or Supreme Reality is Lord Shiva Himself and the whole creation is His manifestation.

He is consciousness and Bliss. Everything emanates from Him and everything merges in Him. He is in us and we are in HIM. In reality, Kashmir Shaivism is a spiritual quest for an inward journey and search rather than an outward one. It is the exploration and realization of the divinity within ourselves. Lord Shiva is also known as Mahadeva-the Great God, Triloki Nath-the Lord of three worlds, Umapati, Gauripati, Parvatipati,Chandrashekhar-the moon-crested, Gangadhar-the bearer of Ganga, Girisha-the mountain Lord, Mahakal -the Lord of death, Pashupati-the Lord of beasts andVishwanath-the Lord of Universe. HE is the Lord of his spiritual consort, the Goddess Parvati, which in reality is the cosmic energy. The union of Lord Shiva with Shakti is Shivratri. Every Monday is sacred to Lord Shiva. Generally, the fourteenth day of the dark half of each month is called Shivaratri. But the one that falls on Phalgun (February-March) is Mahashivratri. Mahashivratri known as 'Hayrath' in Kashmir is a twenty three days festival, which starts from Phalgun Krishna Paksh Pratipada (Phadgun gatapach Oakdoh), the first day of the dark fortnight. It culminates in Phalgun.

Shuklapaksh Ashtami, known as 'Tila Aetham'. On Shivratri, the sun and the moon are usually in the Zodiac sign of Aquarius or Kumbh Rashi. Kashmiri Pandits perform Shivratri Puja called Vatak Puja on the intervening night of Triyodashi and Chaturdashi, while in the rest of the country, people observe Mahashivratri on Chaturdashi.

Shivratri is also known by the names of Mahashivratri, Kalratri and Talaratri. Shivratri, the night of Bliss, has a special significance as the Divine Mother symbolically merges with the divine Lord, thereby establishing non-dualism in the Absolute form. It is also believed that Jyotir Linga appeared on the earth at midnight during the intervening night of Triyodashi and Chaturdashi to remove darkness and ignorance from the world. As such the great night of Shiva is said to commemorate the auspicious advent of the divine Mahajyoti or Supreme light. According to the holy Hindu scriptures, the festival of Mahashivratri also signifies the day on which Lord Shiva saved the world from total annihilation by drinking the deadly 'Haalahal' poison, produced during the great churning of the ocean (Samandhar Munthun). According to sacred texts at this time a forceful natural upsurge of energy is said to take place in the human system, which advances the process of soul purification and enlightenment. This energy in combination with the significant planetary positions help in the upward flow of the energy flow in the human beings. These energy forces help us to overcome the Karmas and raise one's consciousness beyond the veil of illusion resulting in the intensification of the spiritual process.

Lord Shiva also represents the life cycle of living beings. It is due to this very fact that walnuts are used in the Shivratri puja. Walnuts, known in Kashmiri as 'doon' is a seed, which in reality represents a complete life-cycle i.e. the beginning and end of life. It is also a miniature representation of our universe and is symbolic of our respect for the entire cosmos. The four kernels of the walnut are also believed to represent the four directions of the hemisphere and the four Vedas.

As Mahashivratri falls on the darkest night of the year, it symbolises the darkness of ignorance and Lord Shiva is said to manifest Himself during this night to enlighten the universe by removing the ignorance.

As per a prevalent belief in Kashmir, the Divine Couple of Lord Shiva, and Goddess Parvati visit the devotees' homes on the night of Mahashivratri and are said to stay as Divine Guests upto Amavasya, known as 'Doon Mavas' locally (fifteenth day of Phalgun Krishnapaksh). Preparations such as cleansing of the house and washing of the clothes for celebrating the Mahashivratri festival are done from 'Hur Oukdoh', the first day of Phalgun Krishnapaksh to 'Hur-Shaeyum' (Sixth day of Phalgun Krishnapaksh). 'Hur-Satam' is the day when special dishes as per the individual family ritual or 'reeth' are cooked.

On 'Hur-Athum', the devotees prior to their forced migration used to visit Hari-Parbat Srinagar for night long meditation and Bhajan Kirtan at Chakrishwar and Pokhribal temples. It is on 'Hur-Navum' that womenfolk visit their parental homes. On their return, they bring alongwith them the 'Kangri' (the traditional fire-pot), a pack of salt, 'rotis' (bread) and some money locally called 'Atagut' as 'Shivratri Shagoun'. Next comes 'Dashmi' called 'Dyare-Dahum', which has a special significance for the newly-wed Kashmiri Pandit brides. They return back to their in-laws bringing with them new clothes and 'Hayrath-bhog' in the form of cash and kind. It is on this day that vegetarian or non-vegetarian food are cooked as per the family ritual or 'reeth'. It is followed by 'Gada-Kah' (Phagun Gatapach Kah), wherein fish is cooked as per the family tradition. This day has got tantric significance as per the Hindu mythology. On the following day called 'Vagurbah', a small earthenware pot known as 'Vagur' is installed amidst elaborate rituals in the pooja-room, locally known as 'Vatak-Kuth'.

Late in the evening after performing 'Vagur Pooja', cooked rice, vegetarian or non-vegetarian dishes depending upon one's individual family 'reeth' or ritual are offered to the 'Vagur'. This day is followed by 'Hayrachi-Truvah' (Triyudashi), which is the auspicious and most sacred day of Mahashivratri. On this day, an elderly lady of the family fills-up the earthen-pitcher designated as 'Vatak-Nout' with fresh water and a good number of walnuts, usually 101 or 151. This ritual known as 'Vatuk-Barun' is performed before the sun-set. The 'Vatak-Nout' is a symbolic representation of Lord Shiva, whileas a smaller earthen-pitcher, locally called 'Choud' placed adjacent to the 'Vatak-Nout' represents the Goddess Parvati. The smaller earthenwares such as 'Sanivari' (two in number), 'Machvari' (2-4 in number) a hollow cone-shaped 'Sanipatul' representing lord Shiva and a 'Dhupzoor (an earthen dhoopstand) are suitably placed near the 'Vatak-Nout'. In addition to them, two bowl type earthen-wares 'locally known as 'Dhulij' are also placed in close proximity to the 'Choud'. The 'Dhulij', 'Sanivari' and 'Machvari' are believed to represent Bhairvas, 'Gandharvas'- (the celestial musicians) and the other deities of the 'Divine-Barat' (the celestial marriage of Lord Shiva and Parvati).

A small bowl called 'Reshi-Dulij' occupies a special place near the 'Vatak-Nout'. Only cooked rice and milk are offered to it. The 'Nout', 'Choud' and 'Dulij' etc. are referred as 'Vatuk' and are seated on special pedestals of dry grass made in the form of circular rings locally called as 'Aarie'.

The 'Vatuk' is decorated by tying mouli (narivan) i.e. string of dry grass embellished with marigold flowers and 'bael-pater', which is known as 'Vusur'. Tilak is also applied to 'Vatuk'. Incense, dhoop, camphor and ratandheep form the main ingredients of ritualistic material called 'Vatak Samgri'. Milk and curds and conical sugar preparation called 'Kand' are offered to the 'Vatak-Raz', represented by the 'Nout' amidst elaborate ritualistic pooja and chanting of the holy mantras, collectively known as 'Vatak-Pooja'.

As part of the ritual, special vegetarian or non-vegetarian dishes according to one's family ritual or 'reeth' are offered to the 'Dulij'. The day following 'Hayrath' called 'Shivachaturdashi' is locally known as 'Salam'. Salam is a day of greetings and festivity. On this day, all the family members and near relatives are given pocket-money called 'Hayrath-Kharch' by the head of the family.

During Shivratri days, playing of indoor-game with the sea-shells, locally called 'Haren-gindun' is a usual practice especially among the children. Late in the evening of 'Amavasya' known by the name of 'Doon-Mavas', pooja is performed either on the river bank (Yarbal) or at home as per the family tradition. The practice of performing pooja of walnuts taken-out from the 'Vatak-Nout' called as 'Vatuk Parmozun'.

'Doon-Mavas' is also known as 'Demni-Mavas' as some families (Gourit families) prepare meat preparations in combination with turnip as per their family ritual.

It is a usual practice in most of the house-holds, who perform pooja at the river-banks to allow the head of the family to enter the houseonly after he promises blessings and boons in the form of health, wealth, education, employment, peace and prosperity to each and every member of the family. The conversation in Kashmiri, which takes place between the head of the family (who is outside the closed door, and senior lady of the house goes like this, "thuk or dubh-dubh', kous chuv?, Ram Broor 'Kya Heth?, Anna Heth, Dhana-Heth Doarkoth, Aurzoo Heth, Vidya, Kar-bar, Te Sokh Sampdha Heth.'

Shivratri 'naveed' in the form of water-soaked walnuts and 'rotis' is distributed among near and dear ones during the period of 'Doon-Mavas' to Tila-Ashtami, locally known as 'Tile-Aethum', which falls on Phalgun Shuklapaksh Ashtami.

On Tila-Ashtami, a number of earthen oil lit lamps are placed at different places starting from one's home to the river-bank (yarbal) and also one of the oil lamps is made to float on the river with its base seated on grass ring or 'arie'. The day of 'Tila-Ashtami' also signals the end of the severe cold of winter and advent of the pleasant season of spring, locally known as 'Sonth'. On this day, the change-over of season is celebrated by children by burning old fire-pots (Kangris), stuffed with dry grass and tied with long ropes are rotated around in the air, all the time uttering the words of 'Jateen-Tantah'. It marks the final good-bye to the holy festival of Mahashivratri or 'Hayrath'.

Maha Shivratri - Revisiting Kashmiri Ritual Variants

PART I

Festivals are vibrant representatives of traditional values, cultural and religious ethos and mythologised past. The various rituals and religious rites having localised distinctive uniqueness are vital components of festivals. They add substance, strength, warmth and spiritual colour to the weave of human life. The indigenous ritual variants of Kashmiri Maha Shivratri carry multilayered mystic truths and meanings. They not only denote ancient roots but also our cultural and religious moorings. The various Shivratri rituals having a time wrap of antiquity signify centuries old beliefs, traditions and wisdom. The festival is believed to symbolize the celestial wedding of Lord Shiva and Goddess Parvati and that of Goddess Sati in Her previous birth. As per a belief, the auspicious divine function was solemanised by the Lord Brahma Himself in present of all Deities, Rishis and Saints. Maha Shivratri is an eagerly awaited and enthusiastically looked forward festival as Lord Shiva, the great God of the Universe is the most favourite and lovable God, WHO is revered equally by all the Gods, human beings and the demons.

Lord Shiva represents a contrasting life of a householder and an ascetic.

Lord Shiva also connotes a happy and contented family life, Who is believed to reside in the snowcapped mountain of Kailash along with His ever auspicious spouse Goddess Parvati, sons Lord Ganesh, Lord Kartikey and a host of His faithful attendants like Nandi, Kubera, Yakshas, Gandharvas and other 'Ganas'. Rightly Kailash mountain is also known by an alternative name of 'Ganaparvata', the mountain of 'Ganas' as it is frequented by all the Deities, saints, sages, demi-Gods and the Divine incarnations. As per a popular lore, Lord Shiva also personifies the frightful and disturbing aspect of nature in the form of snow and harsh chilly winter. It is one of the reasons that Maha Shivratri is celebrated in the severe and rough winter. The festival celebrated in the night designated as 'Kalratri' also symbolises ignorance, obscurity, seclusion, tranquillity, quietness, impiety, depravity, incomprehension and degradable imperfections. Lord Shiva is the only Supreme God, who grants redemption from all these imperfections. The dark night of Maha Shivratri is also a metaphor for 'Tamogunic' aspect as Lord Shiva is believed to have revealed His divine appearance just before the Universe stepped into 'Kaliyuga', the fourth and last era of Hindu mythology.

Lord Shiva is also regarded as the foremost God of the whole Universe, which comprises earth, sky, air, fire, sun, moon and space. Lord Shiva is also known as the lord of music and dance, both of which are regarded as the divine arts. Lord Shiva is also the God of 'Prates', 'Pischas', Kirates, demons, goblins, ghosts, wandering spirits, the forest spirits of Yakshas' and the troublesome forces of the Universe. It is indicative of the benevolent nature of Lord Shiva, Who is believed to give refuge and shelter to all those, who feel rejected, disregarded, ignored and margianlised. The festival also signifies all that is sacred, pious and auspicious in this Universe. As such, as a run-up the preparations for the festival start nearly a month in advance as the whole house is spruced-up and readied for the welcome of the divine spouses and the divine guests. In tune with the aupiciousness of the Cosmic alliance, all the dress-up attires, utensils are washed and old earthen utensils are replaced by the new one's. The smearing of the house with a mix of mud, water and cowdung and use of earthenwares in the pooja are metaphors for the essential element of Earth, which speak volumes about earths generosity and benevolence.

The various Shivratri rituals, which are deeply embedded in our social life denote the celebration of mythologised heritage and indigenous individuality of our presence. The glory of these rituals is like a sweet memory for Sh. P.L. Razdan, an erstwhile resident of Purshiyar Srinagar and now stationed at Subash Nagar, Delhi. He recalled with pride that ritualistic 'Panch-ratri' pooja was an essential component of Shivratri festival in the earlier times. According to him, apart from the customary 'Vayur', two water-filled vessels known as 'Auster Kalash' and 'Mantar Kalash' were reverently seated on the left side corner of the Pooja-room. On the day prior to 'Haerath', in addition to 'Vagur' eleven number of earthenwares known by the name of 'Haerkai' occupied a reverential place in the Pooja-room, They were regarded as special invites for the sacred occasion. On the Shivratri day, in addition to 'Vatuk Bhairav', one more set of eleven earthenwares designated as 'Vatkai', six number of clay pots known as 'Khaterpals' and an additional set of eight more utensils collectively called as 'Asht Bhairav's' were an essential component of Pooja vessels. The eleven 'Vatkai' are said to represent the divine 'barat', while as the eight earthen utensils of 'Asht Bhairav', 'Symbolize the eight guarding deities of Srinagar city, who as per a religious belief are under the direct supervision of Lord Shiva. The 'Asht Bhairav' are also regarded as the body-guards of Lord Shiva. The notable exclusion of the usual wide-mouthed vessel 'Dul', representation of Goddess Parvati is peculiar to Shivratri pooja of his clan. An enormous quantity of flowers along with 'Arg' (a ritualistic mix of dry rice grains and flowers, was used in the 'Panchratri' pooja performed upto midnight for the first five day's of the festival. Speaking further, Sh. Razdan revealed that on 'Amavasya' locally known as 'Doon-maves', in addition to the family members, all the close relatives including married daughters and sons-in-law would join the ritualistic pooja, which would continue upto midnight. The 'doon-mavas' pooja was performed amidst the recitation of 'lila rabdha' stories and offering of Sugar Candy (Kund) offered to the vessel of 'Vatuk Bhairav' and waving of 'ratan-deep' brought individually by them. The said pooja would culminate with the mixing of water contained in 'Astur Kailash' and 'Mantar Kalashi' vessels with a connecting Kusha grass woven string remaining on both the vessels during the ritualistic mixing. The Kusha grass string was known by the name of 'Ginan Khadak'.

Afterwards, drops of mixed-upwater were sprinkled on the house inmates with the help of 'Ginan Khadak' amidst the recitation of 'Bahu Roop Garab' sholkas. As a final part of 'Amavasya' ritual, pooja was performed on the river bank of 'Vitasta' at midnight with rice flour made rotis locally known as 'Chochivar' and fried sheep liver pieces forming the main pooja ingredients.

The festival of Shivratri is like a walkdown on the memory lane for Sh. Bushan Lal Bhat, original resident of the village Chanderhama, district Baramulla and presently living at Paloura Jammu. Recapping the holy festival, he recollected that seven different items consisting of rice, haize, moong, barley, cooked rice and cotton seeds, locally called 'Kapsi tout' were put in a water filled earthen vessel called 'Satae Laej' on Shivratri day.

A few families of the village would also offer uncooked fish to the 'Bhairav Dul'. A small portion of snow usually procurred from the shady area of the village called 'Asthan' also formed an important offering. On 'Tila-Ashtami' evening, walnut shells filled with edible oil were utilized in place of oil lit earthen lamps. As per a local belief snow offering and oil lit walnut shulls give a touch of auspiciousness to the occasion.

The oil lit walnut shells were usually kept at the front door of the house, front varandah, courtyard wall, ash-storing container (Soore Laej) and cow-dung heap, locally known as 'gush loedoh'. Recollecting the festival celebration of the yore, Sh M.L. Kemu, an erstwhile resident of Zaindar Mohalla Srinagar and presently at Kunjwani Jammu opined that rituals lend a sense of belonging and an area specific identity to a community. He recollected that offering of a live fish locally known as 'neej gadh' to the designated vessel of'Bhairav-Dul' was an integral part of Shivratri ritual. Reminiscing about the festival, Sh M.K. Khushoo, an original resident of Wazapora, Alikadal Srinagar recalled that a few families in his neighbourhood would offer a small part of sheep's hair coating locally known as 'moon' to 'Bhairav Dul'. In case of its' non-avalability, the said offering was substituted by unspure cotton. Recollecting further, he revealed that a small quantity of liquor was also a part of ritualistic offering to the vessel designated as 'Vatuk Nath'. A few drops of the liquor put on the palins and taken as 'naveed' by the house inmates was also an integral part of religious faith.

Memories of Shivratri celebration at Srinagar are like a sweet recollection for Sh. Papuji Khazanchi of Sathu Barbarshah Srinagar and now a resident of Bakshi Nagar Jammu. He recalled that sheeps' lungs alongwith heart put on an oval earthenware called 'toke' as a token of sacrificial offering during 'Shivratri Pooja' was led to the kites on the following day of 'Salam'. According to him, apart from the lavish delectable meat cuisines, the preparation of roasted minced meat was a special meat offering to the specific pooja vessel of ‘Bhairav Dul’ on Shivratri festival. Sh. Papuji Khazanchi also recounted that fragrant smell of incense resulting from the burning of gugal, locally known as 'Kanthgun' and black seasome seeds was ensured for the entire length of Shivratri Pooja as it's fragrance and aroma are believed not only to please Lord Shiva but also to ward off evil and negative influences. Sh H.L. Bhat, hailing from Sangam, Kokernag Anantnag and now resident of Durga Nagar, Jammu regards rituals as watchwords of a festival as they reinforce our implicit faith for the time-tested traditional customs.

Recounting the Shivratri Pooja of yesteryears he reminisced that about seven families of his village would make a sacrificial offering of coagulated blood of slaughtered sheep to the designated pooja vessel of 'Bhairav Dul'. It was procured either from the butcher or from the village abattoir (Zabahkhana). He also stated that a preparation of cooked lungs offered to 'Bhairav Dul' was also a part of tantric rituals.

PART II

Undeniably the festival of Maha Shivratri has a local essence, indigenous character, ethnic attribute and native flavour. It has acquired diverse hues and colours in the form of various symbolical and allegorical strains over the years. The symbolic dimensions of our rituals and customs have given a near heritage status to our socio-cultural history. The various rituals which run through our social fabric give a continuity to our exemplary culture, opined Sh. A.N. Koul, an original inhabitant of Narpirastan, Fatehkadal Srinagar and now a resident of Vijay Nagar, Talab Tillo Jammu. Reminiscing about the festival of old times, Sh Koul revealed that ritualistic dish of 'rajmah' cooked with turnips was a must on 'hur oakdoh', while as the mixed dish of meat and nadru (lotus stem), fish cooked with reddish and indigenous vegetable of 'hakh saag' were the mouth watering culinary delights, which were offered to the 'Bhairav Doul'.

Elaborating further, he recounted that in addition to ensuring of continuous burning of oil lit earthen lamp (choang) through out the festival night in the'vatak-kuth', an elderly male member of the family would also sleep there on the Shivratri night to ensure symbolic family hospitality to the 'divinebaraatis' . Sh A.N.Koul also added that on the occasion of 'Vatak Parmuzan'done on 'Doon Mavas' i.e. Phaghun Krishna Paksh Amavasya, the cutting of river water seven times with a knife while performing the pooja on Vitasta (Jehlum) river bank ghat was an integral part of 'Doon Mavas' pooja. He has not abandoned this ritual even at Jammu as it's continuity is ensured by symbolic cutting of the tap water flow seven times with a knife during the'Doon Mavas' pooja now performed at home instead of the river bank. The time honoured Shivratri rituals carry the resonance of the mystic tradition handed down to the posterity by our ancestors, articulated Smt. Renu Koul (Misri) of Zainadar mohalla Srinagar and now a resident of Talab Tillo,Jammu.

She recollected that Shivratri festival was collectively celebrated by all the five Misri families of Zaindar mohalla Srinagar and mixed preparations of meat and nadru, fish cooked with reddish (muje) were the ritualistic ethnic cuisine offerings during the pooja. Smt. Renu Koul also informed that in addition to the ritualistic ordination of two earthen pitchers (Nout) designated as 'Ramgoud', nine big size narrow mouthed earthen pitchers, nine wide mouthed smaller dimension pitchers called in vernacular parlance as 'doulji' , two clay utensils called 'vagurs' in addition to the usual 'Resh Doul', two'Saniwaris' and one 'Sonipatul' formed an essential part of 'Vatuk' of Misri clan pooja.

Our commitment to the observance of ancient rituals should be firm and steadfast, observed Sh Raj Nath Koul, an erstwhile resident of Rawalpora Srinagar and now living at Vijay Nagar, Talab Tillo Jammu as according to him the rituals chronicle our centuries old cultural and religious history.

Supplementing his assertion, he recollected that he made it a point to procure the fish needed as a ritualistic dish from the distant Telbal area, when fish were in short supply due to freezing of Dal Lake and other water bodies in the year 1984. Rituals are beliefs in the symbols, which give a sort of spiritual and religious fortification to a festival, stated Sh.Makhan Lal Bhan, earlier a resident of Khardori Habbakadal, Srinagar and now settled at Jaipur. Sharing his fond memories about Shivratri, he recollected that after Phagun Krishan Paksh Panchmi, the house inmates would refrain from taking tea or meals outside and outsiders excepting 'Gurtoo' families were disallowed from entering the home. Adding to it, Sh. Bhan also recounted that it was customary to fill-up the 'Vatuk' earthen wares with the water from the river Vitasta and the exercise was usually undertaken by the ladies. Rituals are inextricably linked to our ethno-religious identity and should be celebrated with unbroken tradition as they remind us of our native geography and original locale, affirmed Sh. P.N. Bhat of Zainapora Shopian. Recapping the Shivratri tradition of earlier times, he fondly reminisced that a small fish variety locally called 'gurun' fried without oil on a frying pan was a traditional offering to the designated clay utensil of 'Bhairav Doul'. He also informed that snow and icicles locally known as 'Shishirghant' also formed a part of ritualistic offering to both Nout' and 'Doul', the earthen pitchers as the supreme God Shiva is regarded as the Lord of snow.

The festival rituals having religious essence and spiritual connotations should not get diluted in the time wrap of the present, declared Sh. Jagan Nath Koul Sagar of Manzgam, Kulgam (Kashmir) and now putting-up at Lakshmi Nagar Muthi Jammu. According to him 'Vatak Raaza' is a local honorific given to the great God Shiv Nath as Kashmir is Lord Shiva's and Goddess Parvati nee Satis' own land and mystic paradise. He also added that every past memory of the festival and the native landscape gives a sense of area specific belonging to the community.

Speaking on a nostalgic note, Sh. J.N. Koul Sagar recollected that thirty three earthen utensils comprising of three 'Bhairav Douls', seven Resh pyala's, three wide mouthed pitchers of 'Doulji', apart from the customary utensils of'Nout' and 'Choud', two Saniwari, one 'Sanipatul' and a 'duphjoor' were a part and parcel of Shivratri pooja utensils, collectively known as Vatuk'. Adding to it, he further remarked that Shivratri for Kashmiri Hindus is a festival of rejoicing as it marks the celebration of the divine marriage of Lord Shiva and Goddess Parvati nee Sati. As such all the necessary functions and rites before and in the aftermath of marriage function are performed by us as Goddess Parvati is regarded as the daughter of Kashmir and Lord Shiva as the divine son-in-law. It is due to this reason that all the auspicious marriage rites and symbols are strictly adhored to during the observance of the festival. Accordingly in tune with the requirement of the ceremony, the earthen utensil of 'Doul', a symbolic representation of Goddess Parvati is kept on the left side of the designated utensil of 'Nout', taken as a representation of Lord Shiva as during a marriage ceremony also, a bride is always seated on the left side of the bridegroom. Sh Koul also recounted that as per his clan tradition the ritualistic immersion known as 'Vatuk Purmoojan' was done onPhagun Shukla Paksh Pratipadhav i.e. 'Oakdoh' instead of the usual Phagun Krishna Pakash Amavasya as planetary configuration on 'Amavasya' is as pre a belief regarded as ominous. It is testified by a Kashmiri maxim 'Maghi Gach, Mavsi Na' i.e. never on Amavasya but reluctantly on Maghi.

Rituals are repositories of ancient wisdom and traditional beliefs and have imprints of bygone eras, opined Sh Prem Nath Bhat Shad, an original resident of Qazibagh, Budgam Kashmir and now putting up at Barnai, Jammu. He went nostalgic while recalling the festival of yester years and recapped that use of brass utensils in the Shivratri pooja was disapproved and instead the utilisation of clay utensils was a common practice. The procurement of a live fish (guran) even from the frozen village stream and kept alive in a water container for the eventual offering to the 'Bhairav Doul' on Shivratri was a customary ritual for his family. In addition to it, the cooked fish with separate pieces of head, middle and tail portions was also a ritualistic offering to the 'Bhairav Doul'. Sh. Shad also revealed that it was obligatory for the head of the family to sleep in the Vatuk Kuth' on Shivratri night and also to keep an oil lit earthen lamp burning day and night upto 'Amavasya' in the 'Vatuk Kuth'.

According to him, apart from the relatives, neighbours, friends, the village carpenter, ironsmith, potter and barber would invariably drop in to extend festival greetings on the day following Shivratri, locally known as 'Salam'. It was also binding for the family head to see his face in the mirror brought by the village barber as mirror is said to double the festive mood of the auspicious occasion. Rituals are summation of past experiences and ancient knowledge, which have percolated down to our lives from prehistoic times, commented Sh Avtar Krishan Ganjoo of Ganderbal town, Kashmir and now putting up at Govt. Quarters, Jewel Jammu.

According to him, a few families having the surnames of Tufchis', Thaploos' and Naqaibs' of Srinagar city and the village Vanpoh of district Anantnag had an unique and peculiar Shivratri ritual. An elderly male member of the family would remain awake the whole night on Shivratri in the 'Vatuk Kuth'. During his night long vigil, he would strike the bronze thali with a stick tied with peacock plumes and coloured cloth strips upto the wee hours of the day following it. He also revealed that a few families of Srinagar had an unusual tradition of giving a customary ritualistic bath with liquor to 'Sanipatul', the representative linga form of Lord Shiva during Shivratri Pooja. Our cultural history rests on an ancient edifice and rituals constitute the sentinels that fortify our ties with the splendour of the past, emphasised Sh.Vijay Wali of Narpirastan, Fateh Kadal Srinagar and now a resident of Subash Nagar Jammu. He also revealed that reverential instalation of a clay utensil known as 'Vagur' in the Vatuk Kuth' on the day prior to Shivratri amounts to the creation of festive atmosphere before the symbolic arrival and reception of the divine baraat' on Shivratri. Like a delectable marriage feast, ethnic mutton delights of 'rogan josh', 'Kalya', minced meat dish of 'masch' and fish and nadru preparations are cooked to be offered amidst elaborate pooja to the 'Bhairav Doul' and other clay pitchers regarded as the 'divine baraatis'. In contrast to it, meat offering to the designated utensil of 'Resh dul' is strictly forbidden and in it's place offering of milk, sugar candy locally called 'Kand' and Kishmish are made to it. Many families had the tradition of puttingsaderkaanj' (a fermented cooked left over vegetable and rice starch preparation), sour liver dish known as 'chok charvan', liver pieces roasted on charcoal and a local preparation of goat legs soup known by the name of'Pachi Rus' or 'Pakmond Rus' in the 'Bhairav Dul' in accordance with the individual family reeth'. A few families as per the family ritual desist from cooking meat on Phagun Krishan Paksh Amavasya but instead prepare methi mixed with nadru, nadir yakhni, moong daal mixed with turnip yellow cheese dish and fried sliced nadru called 'nadir churma'. A considerable number of families both in rural and urban areas carve-out different figurative images out of kneaded rice flour, which are known by the local names of 'Shaiv'(mutilated pronunciation of Shiv), 'Shavin' (Lord Shivas' Shakti), 'Kraej(potters), 'Hond' (goat) and 'Hangul' (Kashmiri variety of stag). They are subsequently cooked without oil on the frying pan. Amidst incantation of religious mantras tilak is applied and red coloured religious wrist band called'Naervan' is tied to the fried figurative rice flour carvings of Shiv' and 'Shavin' during Shivratri pooja. Afterwards, they are reverently placed in a thali and on 'Amavasya' evening they are also taken-out to the river bank ghat for the traditional 'Doon Mavas' pooja. The rituals woven with varying strands of centuries old faith evoke blissful memories of the past, nostalgically recalled Sh. Moti Lal Mattoo, an erstwhile resident of the village (Deegam) Kapalmochan, Shopian Kashmir and presently putting up at Barnai, Jammu. According to him, the festival for Kashmiri Hindus is akin to a marriage function and accordingly many rituals which enliven the elated mood of the joyous occasion form a part of the festival. The devotees of his area would use the fragrant wild foliage locally known by the name of'Ganpatar' in place of the usual 'Baelpatar' (Bilva leaves), which grew luxuriantly in Kushaldar forest area of his village. According to him, the ritual of 'Doon Mavas' performed on the river bank represents the ceremonial send-off of the divine bride, divine bridegroom and the 'divine baraatis'. Further, water a metaphor for the power of nature and remover of all sins is an essential requirement for social, cultural, religious and spiritual growth and sustenance. Recapitulating further, Sh Mattoo recalled that during 'Doon Mavas' pooja, the filled-up water contained in 'Nout' and 'Choud' are mixed together before emptying them in the flowing river water symbolizing the divine union of Lord Shiva and His spouse Goddess Parvati Afterwards, a portion of water collected from the river is sprinkled on the front door of the house as a token of auspiciousness.

*(The writer is a keen socio-cultural researcher)

PART III

Festival Customs in Gurtoo Families

The rituals are traditional beliefs representing iconic symbols, which have layers of stories, legends and ancient wisdom embedded in them. They also give valuable insights into social, cultural and econmic expressions of human presence inthe bygone times. Many Kashmiri Pandit families follow a strict code of conduct supplemented with overriding faith and enormous devotion in observing Shivratri rituals. These families are recognised by the surnames of Gurtoo, Malla, Kak, Jailkhani and Naqaib’s. In addition to them, a few families belonging to the surnames of Raina, Razdan, Bhan and Tikoo’s also follow a rigid vegetarian and undiluted customs handed over to them both orally and by practice. For them any derelection in observance of the traditional rituals is not only a religous offence but also an unparadonable sinful act.

Due to the unquestionable faith reposed in the established rituals, all such families are broadly known by the name of Gurtoo’s The ritualistic purity sustained with unbroken devotion and faithful allegiance spanning over centuries of time is a characteristic and pronounced feature of them. The fierce religious discipline and amazing purity exhibited by them in guarding this indigenous strain of religious variant exemplifies their unaltered tradition. They deserve all the accolades and acclaim for having preserved their centuries old clan specific rituals and in the process also having kept their essence intact.

Driven by immense faith, the Gurtoo families desist to blur the traditional line as even a minute abberation or wrong doing in the ritual observance is believed to have fearsome outcome. The Shivratri rituals of Gurtoo clans not only strike a connectivity with the preceding times when Vaishnavite influence occupied a pivotal space in our belief system but also represent a spill over of the past in the form of their present day rituals.

Interestingly, the word ‘Gurit’ is also associated with the best quality clay inKashmir which is known for the finest purificatory properties. Locally known as ‘Gurit Maech’, it is procured from Sampora area of Pampore tehsil of Pulwama district of Kashmir. Incidentally, it is not without reason that ‘Gurit Maech’ or clay mixed with water and cowdung is utilised for smearing the rooms, whenever the houses in Kashmir are to be spurced up for the auspicious events as it is supposed to remove all the traces of contaminations and ensure wholesome purity. Likewise , all those families, who steadfastly adhere to the purity of the rituals are commonly referred as 'Gurtoo's in Kashmir.

The Gurtoo rituals are sacred commitments, which make us feel close to the Divine, opined Smt. Chunji Gurtoo, an erstwhile native of Kharyar, Habbakadal Srinagar and now putting up at Anand Nagar, Bohri Jammu. She informed that in Gurtoo families, the intake of non-vegetarian food including'Tamsic' one is totally given up from Phagun Krishan Paksh Dashmi and vegetariansim is stictly followed. From that day in accordance with the 'Gurtoo specific clan strictures, excepting for 'Sattvic' vegetables, fruits and milk, the purchase of cheese and bread and getting them inside the house is forbidden. Adding to it, Smt. Chuniji disclosed that in earlier times, on this days all the used earthen cooking untensils were broken and replaced by the new religious one's. The adherence to the code of purity and piousness was so obsessive in the earlier times that Gurtoo families would not spare even the clay container used for storing charcoal ash locally known as 'Soore Laejh'.

Apart from it, even the iron vessel used for holding edible oil, locally known as 'Tila Vaer' was put inthe roaring fire of the indigenous mud hearth (dhaan) to ensure the removal of all traces of impurity.

She also revealed proudly that day's ahead of the festival, painstakingly efforts and extraordinary care were undertaken to ensure scrupulous and spotless cleanliness of the house by smearing it with a mix of 'Sampur' clay, water and cowdung. The purificatory act of cleansing locally known as 'livun'was accmplished with enormous faith even in the wintry chill. Continuing in the same vein, she recalled that on 'Dyara dahum'. i.e. dashmi, the potter and in some families potteress would deliver the earthen pooja vessels, called 'VatakBane', and freshly baked cooking untensils to be used for the entire year. In line with the auspiciousness of the occasion the utensils were taken inside the house after the ritualistic waving of water filled vessel around the potter and the utensils. The ritual known by the local name of'Aalath' is an act of supplication to the Divine. Likewise, the procurement of the flowers, grass woven spherical seating bases called 'Aarie', grass woven string embedded with flowers and Bilvai leaves, locally known as 'Vusur'were also ensured usually on the same day through a courier known by the local name of 'Push'. Interestingly, 'Pushan' is a deity in the Vedas, having the etymological root 'Push', meaning the nourisher. As per a religious belief 'Pushan is the protector of cattle and of human possessions and is said to bless the bride in marriage functions.

She also recounted that on Phagun Krishna Paksh Ekadashi, eleven saucer shaped earthenwares known by the name of 'Parvav' are seated on grass woven spherical bases 'Aarie' and their ritualistic pooja is performed usually in the morning.

The vegetarian dishes of 'haak', unpounded moong daal in combination either with nadru (lotus stem) or raddish are cooked and a small portion of them mixed with a bit of rice are put in these 'Parvas' as a mark of offering amidst religious invocations. On the next day i.e. Phagun Krishna Paksh Duvadasham, locally known as 'Vagur Bhah', an earthen vessel (nout or'choud') according to individuals family 'reeth' filled up with water and walnuts is reverentially installed amidst pooja.

The rituals is known as 'Vagur Barun' and the most favoured dish is moong daal in combination with raddish. As per a locals belief 'Vagur' symbolises the preparatory welcome extended to the family priest of the bridegroom, who visits the bride's home as a prelude to the actual marriage function. Smt. Chuniji Gurtoo further revealed that on Shivratri a narrow mouthed earthen pitcher called 'Gagar', a symbolic representation of Lord Shiva, a wide mouthed utensil called 'doul' or a small clay pitcher known as 'Choud', symbolizing Goddess Parvati, are reverantailly docked with 'mouli', flowers, Bilva leaves and 'Vusir'. They are afterwards seated on the grass pedestals 'Aarie' in the Pooja room, locally kown as 'Vatak Kuth'. Additionally a small sized pitcher called 'Ram Goud', small earthenwares called 'Sanivarie', ling shaped 'Sonipatul' and Dhoop holder called 'Dhupazoor' are also positioned in the 'Vatak Kuth'. All the Pooja utensils are collectively known as 'Vatuk'the Pooja material as 'Vatak Samagri' and Pooja ingradients as 'Vatak Masola.'.

It was also disclosed that best culinary skills are employed to cook a lavish-spread of vegetarian dishes of 'moong daal' in combination with nadru,'nadru yakhni', sour raddish slices, locally known as 'mujie kaela', deep fried crisp nadru slices called 'nadur churma', 'dum aalu' and sour methi on Shivratri. As per a centuries old reeth, a sort of distinctive ethnic drink having exotic taste and known by the local name of 'Madhu Panakh' is an integral part of Shivratri pooja of most of the Gurtoo families. The various ingredients especially almonds, cardamom, dates Kishmish coconut, bhang (cannabis), jujbee and sugar crystals (nabadh) are thoroughly pounded andmixed with milk to get this specialised brew. It is a symbolic hallucinogenic drink believed to bring heightened consciousness and ecstasy in the worshippers. 'Madhu Panakh' is supposed to eliminate wordly distractions and ignoable thoughts and facilitate communion with the divine. Interestingly, god of the gods, Lord Shiva is said to be fond of narcotic preparation of bhang and milk called 'Siddhi'.

It is due to this reason that one of the names of Lord Shiva is 'Sidheshvara'. On Shivratri, 'Madhu Panakh' is also offered to the earthen utensil of 'Nout'the symbolic representation of Lord Shiva.

Extending her conversation, Smt Chuniji disclosed that Gurtoo families being'Shivkarmis' display boundless devotion and reverence for Lord Shiva. It is in total contrast with most of the non-Gurtoo Kashmiri families, who have endless adoration for 'Bhairva' the fearsome manifesation of Lord Shiva. This varying devotional allegiance has correspondingly influenced the rituals and customs performed by them on Shivratri. In some Gurtoo families, the ritual of 'Parmujan' is done on the day next to Shivratri, i.e. 'Salaam' but in the process, they ensure the clearance of the symbolic sacrificial obltation material done for the departed souls, known by the name of 'Ankan'. It is completed on Shivratri evening itself.

Strangely, in most of the Gurtoo families, the vegetarian 'reeth' or tradition is done away with on Phagun Krishna Paksh Amavasya evening with the cooking of meat preparations of yellow meat, locally called 'Kaliya' or meat mixed with turnips or in combination with goat's stomach, locally called as 'demni gogzi'. It is due to this reason that 'Amavasya in Gurtoo families is known as 'Demni Mavas'. It is in contrast to non-Gurtoo and non-vegetarian families, where 'Amavasya' is designated as 'Doon Mavas'.

A sizeable section of Gurtoo families cook meat dishes on the day next to 'Amavasya' i.e. Phagun Shukla Paksh Pratipidha as they shy away from taking meat on 'Amavasya' due to religious sentiments. Smt Chuniji Gurtoo stated that 'Amavasya' related pooja was performed on the Vitasta river bank. The ritual involved taking the 'Vatak Nout' and 'Choud' or 'dulij' in a wicker basket to the river bank, where their contents were emptied in the flowing water before performing pooja of walnut kernels, which served as'prasadh' or 'naveed' for the devotees.

The 'Visarjan' ritual is followed by symbolic cutting of the flowing river water seven times cross-wise with a knife. Understandably, the symbolic cutting of water reiterates our vows and commitments seven times to perform Shivratri related rituals with reverence, determination and steadfast devotion as the figure seven has a sacred and holy connotation in Hindu religious tradition. The Rigveda speaks of seven underworlds of 'Patala' of the earth known by the names of Atal, Vital, Sutal, Rasatal, Talatal, Mahatal and Patal. They are said to be inhabited by Nagas, Daityas, Danavas and Yakshas etcVitala is believed to be ruled by Hatakeshvara, a close confident of Lord Shiva, while as Vasuki, the king of Nagas or snakes is said to reign supreme in Patala. The holy scriptures also speak of seven upperworlds, which are designated as Bhuvloka (earth), Bhuvarloka (area lying between earth and sun, where Munis and Sidha's are said to reside), Swarloka (region between Sun and Polarstar, Maharloka (abode of Bhrign Rishi and other saints).

Janaloka (abode of mind-born sons) i.e. 'manas-putras' of Lord Bramhav,Taparloka and lastly Satyaloka, also known as 'Bramha Loka', where Lord Bramha is believed to reside. The digit seven also denotes seven holy and pilgrimage cities of Ayodhya, Mathura, Gaya, Banaras or Kashi, Kanchi of Canjeveram, Avanti or Ujjain and Dwarka. Seven also symbolises sevenSaptrishis or Prajapatis, who are also known as 'manas-putras' or mind born sons of Lord Bramha. As per Satapatha Brahmna, they are Gotama, Bharadwaj, Vishwamitra, Jamadagn, Vasishtha, Kashyapa and Atri. According to Mahabharata, they are Marichi, Atri, Angiras, Pulaha, Kratu, Pulastya and Vasistha, Seven also stands for seven names of Rudras, the fearsome and frightening manifestations of Lord Shiva, which are Bhava, Sarva, Ishana, Pashupati, Bhima Ugra and Mahadeva. It also represents seven sacred holy rivers of Ganga, Saraswati, Sindhu, Gomati, Gandhak, Saryu and Beas or Vipasha. The number seven is also associated with'Saptpadhi' ceremony of going around the 'agni' seven times at the time of marriage ceremony, symbolising togetherness of the spouses for emotional strength, wealth, food, progeny, long life, prosperity and eternal association. The said number also represents the seven streams into which the river Ganga is believed to split after descending down from the matted hair of Lord Shiva. The digit seven also symbolizes seven sacred mountains, seven sacred trees of Bilvav, Peepal, Ashvatha, Banayan and Mangoo etc. and seven segments of earth called Jambu, Kura, Palaksh, Shalmali, Kranch andPushkar.

*(The writer is a keen socio-cultural researcher)

PART IV

Festival Customs in Gurtoo Families - II

The Puranas also refer to seven matrikas or Shaktis of Lord Bramha, known as Maheshwari, Kumari, Vaishnavi, Varahi, Andhri and Chamunda, who are invariably propitiated and invoked before the start of a pooja. The number seven also represents seven forms of agni or fire known as Kali, Karali, Manojva, Sulahita, Sudhumarvarna, Ugra and Pradeepta. It also represents seven stages of rebirth through which a human being passes before the soul attains moksha. As per a belief, there are also seven levels of consciousness each of which is linked with the seven chakras of the human body.

Probably, it is due to this reason that the river water is cut seven times during the 'Amavasya' pooja to symbolize the seven vows taken to honour and perform the Shivratri rituals steadfastly. After the completion of the ceremonial 'Amavasya Pooja'. on the river bank, a little water is put in the empty 'Nout' to be sprinkled on the entry door of the house as a mark of auspiciousness.

This ritual is known as 'Kalash Lav'. It is followed by closure of the main door of the house, which is opened only after 'knock at the door' ritual locally known as 'dhub dhub' ends. It is a sort of a conversational exchange of words betweenan elderly lady of the family behind their door and an elderly male member outside it eager to seek entry in the home. The said dialogue is in a token of affirmative and endorsement nod, in which prosperity, tranquility, fortune, well-being and all material comforts are sought and symbolically assured. It is akin to 'Zaem-brandh' ritual of wedding function of Kashmiri Pandits, where sister-in-law of the bride closes the door and opens it subsequently after the bridegroom promises to give the sought gifts to his sister.

In both the rites, the door is a symbol for the very psyche of the house inmates as it transports us into the inner world of family life, psychological security and comfort. Moreover, home also represents a sacred social institution, where human relationships are fortified and cemented on which is based the familial and societal life. On 'Amavasya' i.e. Doon Mavas, as per a native belief, the divine bride Goddess Parvati is believed to depart with Her divine bridegroom Lord Shiva to the bridegroom's home. The pooja is performed on the river bank as the flow of river is ametaphor for life and its' life bestowing generosity. The river water also symbolizes its purifiactory powers as removal of impurities and sins both at the physical and spiritual levels.

Besides, river also represents the symbolic connectivity as an essential link of transportation. The river water also represents the continuity of human life and the life giving order, which is in harmony with the natural rhythm of the universe.

In addition to it, the river banks are also regarded as the dwelling places of gods, saints and sages. Probably, due to these facts the 'Amavasya' pooja is performed on the river banks. Morever, as per a local belief, Phagun Krishan Paksh Ashtami, known in the native language as 'Hur Aethum' is said to symbolise one of the wedding ceremony rites of parting of the hair of Goddess Parvati (mus-mouchravun). Likewise on Phagun Krishan Paksh Pratipadha, known as 'Hur Oakdoh' one more marriage related ritual of house cleansing known by the name of 'Ghare-Navun' is said to commence. The concluding ceremony of Shivratri falls on Phagun Shukla Paksha Ashtami, locally known as 'Tila Aethum'.

It represents the final symbolic send off to all the remaining divine guests of the cosmic 'baraat', who might have stayed back at the bride's home. It is an evening ritual in which oil lit earthen lamps positioned on grass woven spherical bases 'Aarie' are placed at entry door of the house, top of the courtyard wall, enroute path to the river and base of the tree, whileas a few lamps are floated onthe flowing river. The light of oil lit lamps is a metaphor for life. It is also symbolic of the light offered to the departed souls of the ancestors.

The history of our social and cultural development is interepted through time-tested rituals and it is through them that past becomes alive, observes Sh. Vjiay Malla, an original residents of Malik Angan, Fateh Kadal Srinagar and now putting-up at Sarwal Jammu. The 'Gurtoo' tradition is followed by his family with an amazing purity and even a whiff of wrong doing is regarded as a blasphemous act. He disclosed that prior to Phagun Krishan Paksh Pratipadha or Oakdoh, all the cooking utensils are thoroughly cleaned, clothes washed and the earthenware pots are replaced by new ones. He also revealed that from 'Oakdoh' onwards, eatnig or taking tea outside the home is disallowed and even puffing on a stranger's hookah is not permitted.

Sh. VIjay Malla also revealed that permissible vegetarian dishes in his home are 'monji haakh', moong daal and patatoes, while as cooking of 'Soanchal', turnips, rajmah and sun dried vegetables locally known as 'hoakh sabzi' are forbidden.

As per a belief rajmah, turnips and soanchal are regarded as 'dukoal' i.e. equivalent to non-vegetarian food, while as the dry vegetable preparations are not in tune with the auspiciousness of the occasion. Elaborating further he recounted that in earlier times at the time of ritualistic filling-up of the earthen untensil 'Nout' with water and walnuts, the ladies of his home would drape themselves in new outfits and wear new 'Attahoar' in the ears as a mark of good omen. Furthermore, a rice filled up thali having a small quantity of salt was also made to touch the right shoulder of the lady engaged in 'Vatuk Barun' ritual. In the local parlance, this ritual is known as 'Zangi Yun'. Both the rites bear a striking resemblance with the practice followed during the marriage and birth day functions.