Kuldeep Raina

Kuldeep Raina is General Secretary of Panun Kashmir.

Featured Collections

When ‘Literature of Exile’ turns into ‘Exile of Literature’

by Kuldeep Raina

The corpus of literature produced by Displaced Kashmiri writ ers during the past seventeen years remains substantial.

Much of this literature belongs to the realm of poetry, where nostalgia for the lost homeland and religious devotionalism form the main theme. With few exceptions, Displaced Kashmiri writers have steered clear of the option of addressing the core issue i.e. ethnic- cleansing and its varied dimensions.

They have shown reluctance to focus - the forces responsible of Kashmiri Hindus' displacement, the social milieu which facilitated the genocide, the cultural effacement in the wake of cleansing, the state response and the futuristic vision etc. No wonder, the mass of the Displaced Community finds this literature irrelevant, redundant and delinked from their actual life and aspirations.

Displaced Kashmiri writers have not contributed much by way of short story writing/fiction to dilate on the theme of displacement.

Just two works of fiction - ' In the shadow of Militancy', by Prof. Tej Nath Dhar and 'Dardpur' by Kshema Koul have appeared in this prolonged exile. Besides this, there are two collections of short stories-- 'Atank Ke Bheej' by Avtar Krishan Razdan and 'We were and we will be' by Parineeta Khar and few short stories by Hriday Koul Bharti.

Lottey Huvay' (While returning - Sheeraza October 2004-January 2005, by Gouri Shankar Raina, has all the ingredients of a good short story and is written quite artistically. The story is set in post-1990 Kashmir, ravaged by terrorism, where from the indigenous Kashmiri Pandit community stands banished.

The victims of cleansing are unable to visit their homes.

Nevertheless, their yearning to see again their 'fallen homeland', remains constantly alive. 'Kshir Bhawani Yatra, conducted under strict security, becomes an occasion- not only to pay obeisance to the Goddess Ragniya but also to steal a glimpse of their homeland.

It is a torturing experience for the people that they cannot visit their homes where they have been living since ages.

In 'Lottey Huvay' Kashi Nath, the protagonist in the story, too decides to avail the opportunity of 'Kshir Bhawani pilgrimage'.

He visits Kashmir in the company of his son, Pushkar. The latter was a student of 5th standard at the time of displacement.

Kashi Nath used to live in Tankipora locality in the vicinity Habbakadal, once the hub of Kashmiri Pandit community.

Pushkar presently was serving as a bank employee.

For centuries, Kashmiri Pandits have been living on the banks of the Vitasta. This river was a part of their religio-cultural folklore. They used to celebrate its birthday, a phenomenon unique to Kashmir, 'Vyeth- Truvah' with great pomp, gaiety and sanctity. They would conduct elaborate rituals and the river would wear a festive look on this occasion. Even till 1990, most of the localities along the shores of the Vitasta in Srinagar city were predominantly Pandit and permeated with Pandit ethos.

Kashi Nath had intended to cover yatra in two days. While returning from Tulumulla, the pilgrim’s bus halted at Dalgate for refreshments. Aftab Mir, spots his neighbour and friend Kashi Nath among the pilgrims.

When Kashi Nath tells Mir that he had come on pilgrimage and was on way to Jammu, Mir asks him if he would not like to see his home. Kashi Nath turns grim and is unable to decide. Finally, Mir takes Kashi Nath and his son Pushkar with him to Tankipora.

The members of Mir's family receive 'the guests' warmly. The two families ruminate about the good old days when they shared each others' joys and sorrows. As the dusk set in, Mir carried Kashi Nath to his house across the compound. In the abandoned house, Kashi Nath showed to Pushkar the room where the family used to conduct rituals - the Thokar Kuth. Young Pushkar was lost in deep thought while looking at what once used to be his sweet home. In evenings every Kashmiri Pandit family used to light an earthern lamp (Sandhya Chong) to honour the memory of the dead. In a flash of moment Kashi Nath went to fetch a packet of candles and lit these on the platform where once his wife used to wash the clothes.

Neither Mir nor Pushkar could comprehend the significance of what Kashi Nath was doing.

At dinner time Mir brought all the valuables which Kashi Nath had kept in his safe custody at the time of departure. For Kashi Nath, the only things which still retained value were the pictures which used to be hung on the walls of his house.

The following morning -Pushkar decides to visit his colleague a Jammuite, recently transferred from Jammu, at Amirakadal.

When Pushkar does not return in time, it gives tense moments to his father. Pushkar was a precious child, born 15 years after marriage when Kashi Nath was past 40. Bad thoughts keep churning in Kashi Nath's mind.

He wonders whether the city had devoured his son. He moves to the river bank and stares at the direction leading to Amirakadal.

In old times the river bank used to be full of life. Kashi Nath recollects the day of 'Vyeth Truvah', when endless streams of lit earthern lamps would be seen floating in the river. Today the entire surroundings looked desolate, even the Vitasta lacked energy and seemed sad. There were no boatmen waiting to ferry across college/office going Pandits to their destinations.

On learning that a bomb blast had taken place at Amirakadal, Kashi Nath presumes that the worse has taken place. He cries and sobs for his dear son. Aftab Mir tries to reassure him that nothing untoward would happen to his son. Before Aftab's family could contact the hospital authorities to know about the identity of the casualties, Aftab's son accompanied by a police cop land in Mir's house. The cop tells Mir that a blast had taken place in Koker Bazaar and the police had taken Pushkar, who was passing by the street at the time of blast, for questioning to collect information about the terrorists involved.

Reassured that his son was safe, Kashi Nath while looking at his house, begins experiencing hallucinations. He sees the lit Sandhya chong in his house and his wife, carrying lotus flower and milk in a plate, going to the river Vitasta to thank her for safe return of her son. She puts lighted earthern lamp on the lotus leaf and puts it down on Vitasta. What once used to be an endless stream of lighted earthern lamps, the lone earthern lamp, carried by the calm Vitasta symbolises the turbulent times Kashmir was passing through. The writer wonders how long even these visits, symbolised by the lone lamp on the Vitasta, could go on.

The author succeeds in making his point-be it the 'Vyeth Truvah', thanks giving ceremony to the Vitasta or the 'pictures, depicting social heritage - that Kashmiri Pandits valued their 'Kashmiriyat' more than anything else.

The sad part of the story is that it leaves two bad impressions, which negate the reality.

One, it conveys that intercommunal relations had stood the test of times even in the times of ethnic- cleansing. This is simply not true. If the majority community had played a rational role, there would have been no displacement.

Nearly, seven thousand houses of Pandits have been damaged/destroyed, hundreds of houses usurped fraudulently, localities after localities razed to the ground. Even Salman Rushdie, the noted writer, in his 'Shalimar the clown', concedes that the looted goods from Pandits' houses used to be sold in an open market regularly for many years, with no sense of outrage from Kashmiri Civil Society.

May be there might be few families who have played a commendable role. Does a single swallow make the summer? If the behaviour displayed by the Mir family was the general sentiment, why should then the sensible Kashmiri Pandits be rotting in worse conditions in Jammu and elsewhere? Secularism cannot be built by according respectability to communalism. It can survive only when intercommunal relations are crafted on the basis of equality, toleration, humanism and respect for each other.

The other point, equally sinister, is that security forces' emerge as the villains, who do not spare even the pilgrims of the minority community. Aren't we adding grist to the propaganda mill of the anti-national elements.

It is the security forces' who are combating the forces of disorder, lawlessness, intolerance and helping Kashmiri Civil Society to slowly shed its fear.

When literature becomes a device to camouflage the reality the 'literature of exile'metamorphoses into 'exile of literature'.

Displaced writers could do better.

Story of Begum Samru From a nautch girl to a Princess

By Kuldeep Raina

Sardhana is a village within Meerut district in UP. The basilica here is an important pilgrim Centre as a shrine of Mother Mary. The splendid cathedral keeps alive the memory of an extraordinary Christian princess, who built it and ruled Sardhana for 55 years.

Her sculptured tomb, surmounted by Adamo Tadolini's (Italian Sculptor) statuary and the basilica beside it, became an Urs, drawing thousands of pilgrims from all over the country throughout the year every second Sunday of November, and a constant stream throughout the year.

The extraordinary princess was a nautch girl Farzana, whose meteoric rise as Begum Samruastounds even today.

Origins :

The dazzling beauty, Farzana, whose charm even seduced Governor-General, Lord Hastings, was born in 1750. Her origins are obscure. She has been called an Arab, an Iranian or anything else but a Kashmiri. An accidental discovery of a letter in 1925 in Pondicherry archives has established beyond doubt that Farzana hailed from Kashmir.

The letter was written by Frenchman Commander Bussy to Marshal de Castries, Royal Minister of France. This letter was dug out by MA Singervelu, curator of the old records at Pondicherry.

Dancing has remained a popular profession in Kashmir from old times. These dancers have been known as Hafizas.

These dancers - particularly those who were fair or had great charm often landed in Delhi. It was a well-established practice among Mughal notables at the Delhi court to have these Kashmiri damsels as their wives or concubines. One such blonde was taken up by a decadent Mughal noble Asad Khan, who lived at Kutana Qasba, 80 kms north of Delhi. Asad's new mistress had performed for years in a Kotha in Chauri Bazar, before she was taken up by Asad Khan as his concubine.

Farzana was born to Asad Khan and his mistress in 1750.

After Asad Khan's death in 1760, Farzana's mother was not treated well by her step-son. She alongwith her daughter Farzana left for Shajahanabad. After ten days of gruelling journey, the mother and daughter arrived at a bustling sarai near Kashmiri darwaza. Farzana's mother was running high fever and collapsed.

A tawaif from Chauri Bazar, Khanum Jan, attracted by child's cries, brought Farzana to her Kotha.

Khanum Jan:

Khanum's Kotha was among the best in Chauri bazar. Khanum Jan and other troupes of dancing girls were patronised by Englishmen. Syed Hasan Shah, in his autographical novel called Nashtar (first published in 1790, translated into English by Qurrutalain Hyder in 1992, Sterling) refers to charms of Khanum Jan:

"She had a magnolia face and narcissus eyes.

She must have ruined the piety of a thousand men..

our eyes met and I was struck by the arrow of love".

Khanum Jan trained Farzana in her art. Soon, she became one of the most sought after girls of the Kotha in Chauri Bazar. Farzana grew up in the seclusion of tawaif's Kotha.

The later part of the 18th Century has been called 'gardi Ka Waqt' (time of troubles). The period witnessed the progressive replacement of indigenous imperial rule by foreign colonial dependency. The Mughal imperial power declined, many Indian states emerged as independent centres of authority and there was gradual rise of foreign dominance, first French and later the British.

Reinhardt's emergence:

The rise of Indian states saw them utilise the services of foreign military adventurers (some of them from different corners of Europe) to beef up their own illtrained and frequently disloyal levies. One of these adventurers was the so-called General Walter Joseph Reinhardt, who whisked Farzana away from the Kotha of Khanum jan. Reinhardt belonged to one of the poorest regions of Western Austria. His father was a stone worker.

Reinhardt came to India in 1750, boarding a French frigate bound for Pondicherry. He deserted ship on arrival and enlisted in the French army. Leaving the French, he joined the East India Company. During this tenure he changed his name to Sommers, apparently to make himself more acceptable to his new employers.

He soon deserted them, raised his own troops and joined Mir Qasim. At the latter's behest, he murdered about 150 British civilians and POWs, for which the British called him the Butcher of Patna. After Mir Qasim lost out to the company, Reinhardt decamped with the treasure of the Nawab and drifted to Delhi with his troops, providing mercenary services to the highest bidder.

According to Col. Dyce, who subsequently married daughter of Farzana's adopted step-son Zafaryab Khan, Farzana's marriage with Reinhardt was never solemnized. She was a concubine who lived with Reinhardt until his death--but never married to him. The Austrian mercenary picked her up in 1765, when she was just 15, and Reinhardt over 45. Reinhardt, now called Sommers or Sombre, had earlier picked up a concubine, Zafarayab's mother during his hectic years of soldiering. He also maintained a Zenana (Harem). In a fulsome panegyric Zebul Tawarikh in her honour in 1822, Munshi Gokul Chand (who served the begum Samru for many years as Khas Munshi) claims that three sons were born to Farzana from Reinhardt. All of these died. This mystery was never cleared.

Reinhardt alias Samru, was a hunted man, trying his best to keep out of clutches of the British. As his mistress, Farzana alias Begum Samru, learnt the ropes of military command and rode out with him in his campaigns.

The death of Najib-ud-Daula in 1770 paved way for return of Mughal emperor Shah Alam (d.1782) to Delhi in January, 1772. This was a turning point in fortunes of Begum Samru. Mirza Najaf Khan was appointed Amir-ul-Umra. This brought Sombre and his begum out of seven years of relative obscurity into the limelight once again.

Mirza Najaf wanted to push Jats out of Agra. Sombre had a force of 1900 Sepoys, 5 pieces of cannon, 6 elephants besides a few Europeans--a respectable force.

Sombre was bribed heavily and promised much more if he switched his loyalties to Mughals. By the time Sombre joined Najaf Khan, he had already served 14 employers-a fair commentary on his shifting loyalties.

In the battle of 17th November, 1773, Mughals defeated (with Sombre on their side) Jats.

Reinhardt has been described as hardworking, unscrupulous, reckless and a bold military adventurer. He was not known for his fidelity or loyalty to his employers.

The Britishers put further pressures on Mughals to get rid of Sombre. John Lall, who has authored a well-researched book on Begum Samru, observes,

"Reinhardt would have been completely lost in the snake pit of intrigue without his begum's active intervention, directly and behind the scenes".

Sardhana Jaidad:

For their help to Mughals to push out Jats, Sombres demanded the prized tract of Sardhana (with an annual revenue of 6 lakh rupees). In 1776, Emperor gave Sombre a Sanad, at the instance of Najaf Khan. A rover became a landed magnate.

After the grant, Sombre was appointed Civil and Military Governor of Agra. Sombre died in 1778. The French tried to put Zafaryab Khan in succession to him.

Farzana's patron Najaf Khan was at the height of his power, with his title of Zulfiqar-ud- Daula.As long as he enjoyed Shah Alam's favour, her own position was not seriously imperilled.

Farzana's succession was finally tilted by two more factors: She had enormous assets to pay the Sardhana battalions from the huge wealth accumulated by her mercenary husband.

Secondly, by the time Sombre died, Farzana had already established a 'commanding personal performance' with the Sadhana brigade during operations in which it had been involved.

She commanded the loyalty of officers and men of brigade. In the end, it was the united demand of Sardhana brigade that tilted the balance in Farzana's favour. Shah Alam, having personal knowledge of her singular talents and aptitude for business acceded to their request. She took possession of the Jagir of Sardhana and came to be called Begum Sumroo. The emperor's sanad invested her succession with legitimacy.

In the memorial at Sardhana cathedral she is depicted holding the sanad in her hand. Sanad and the unanimous support of her army gave the Begum total authority - legally and politically.

She in turn gave them security, regular and honourable service conditions. Competence as a ruler and loyalty to her benefactors turned Begum of Sardhana into a legend in her life-time. Her ability to command respect and her remarkable gifts as a politician helped her establish and maintain excellent relations with each power.

A woman ruler was vulnerable. Therefore she had to establish a 'Commanding personal presence'. Begum Samru dealt with an incipient mutiny by inflicting gruesome punishment on two slave girls. This made strong impression on turbulent spirit of her troops. She not only established her writ as a firm ruler, but also proved herself to be a just ruler. Through just revenue settlements, she relieved the peasantry from rural indebtedness.

This led to improvement in agriculture and won her the support of peasantry. This gave stability to her rule. Two of her European contemporaries have praised her wisdom in administrative matters. W. Francklin in his History of the Reign of Shah Aulum (London, 1798) writes:

"An unremitting attention to the cultivation of the lands, a mild and upright administration, and for the welfare of the inhabitants, has enabled this small tract to yield a revenue of ten lakhs of rupees per annum (up from six...)".

Major Archer, ADC to Lord Combermere, C in C of the company’s forces, who actually visited Sardhana during the Begum's lifetime unhesitatingly praised her achievements. He said,

"The Begum has turned her attention to the agricultural improvement of the country, though she knows she is planting what others will reap”.

'Zebun Nissa':

Najaf Khan, her protector died just four years after the grant of the Sanad. Delhi was plunged into uncertainty. In 1783 some of Begum Samru's troops were involved in a factional quarrel in Delhi, in which her able and trusted commander Pauli was killed. Some powerful elements, jealous of her, tried to poison the emperor against her.

Rohilla Chief Ghulam Qadir had seized the crown lands in Doab, including a part of her Jaidad. The emperor's promises of financial compensation for the loss had not been honoured.

When Sikhs raided Doab as far as Meerut, Begum alongwith her troops went to Panipat to protect the frontiers of the diminished Kingdom of Delhi. In 1788, the Rohilla Chief attacked Delhi. Emperor Shah Alam appealed to Marathas and Begum for help. Ghulam Qadir, had offered marriage to her, alongwith a share of the spoils if she joined him in taking the Emperor Captive. His offer offended her strong sense of loyalty to her benefactor. She spurned Rohilla Chief's suggestion without hesitation. Before Begum could come to emperor's help, Rohilla Chief had entered the royal palace and blinded the emperor.

Begum Samru promptly hastened to Delhi and stationed herself across the river. Ghulam Qadir was not unaware of her strength. He tried to play a trick and called her sister. She hoodwinked him by promising to help. When the Rohilla Chief had retired to his camp the Begum immediately took control of the palace and pledged her life for the protection and safety of the emperor. Faced with battery of the Begum, the Rohilla chief withdrew. It was left to Mahadaji Scindia to mete out retribution to the Rohilla Chief for his atrocities.

The emperor was restored to the Throne. He bestowed on the Begum the title of Zebun Nissa, Ornament of Women. The crown lands in Doab were restored to her. Subsequently when emperor took to field himself to bring rebellious Najaf Quli Khan to heel, Begum Samru insisted on joining him with three companies and a squadron of artillery.

She also helped the emperor to stamp out indiscipline in his forces at Gokalgarh. Najaf Quli Khan begged Begum to secure emperor's forgiveness. Emperor Shah Alam honoured her again for gallantry and loyalty. This time with the appellation of "his most beloved daughter". She was also bestowed a grant of pargana of Badshahpur Jharsa, near Delhi.

It was in 1787 that Begum's forces were joined by an Irish mercenary George Thomas alias Jahazi Sahib. A dashing sailor, he inspired confidence by his imposing demeanor. After Gokalgarh, he became even Begum's lover. Due to his low social origin, Begum spurned the offers of marriage. He had enormous administrative and military talent. Finally, he was sent to pargana of Tappal.

The Begum came to be credited with virtually legendary powers. Bishop Heber, an Oxford scholar in his Narrative of a Journey through the upper Provinces of India (1828) observed: "Her soldiers and people and the generality of inhabitants of this neighbourhood pay her much respect, on account both of her supposed wisdom and her courage; she having, during the Maratha powers, led, after her husband death, his regiment very gallantly into action, herself riding at their head into a heavy fire of the enemy". Col. Skinner, a European officer wrote of her, “Her best qualities were those of the head. Her sound judgement, her shrewdness of observation, her prudence and occasional fidelity to her trust-chiefly exemplified in her conduct to the unfortunate Shah Alam".

Samra Rehman, in her review of Jaipal Singh's Samru: The Fearless Warrior, strikes a discordant note. She argues that to describe the Begum as The Fearless warrior is somewhat contrary to historical evidence.

Rehman writes : "While she, no doubt, had ample physical courage and was present on many a battle field, she was the de jure commander, whereas the actual fighting was done under one or the other of her officers. For instance, the battle in which the Mughal emperor was saved from a precarious position, it was George Thomas who led the charge. But the Begum who was present in her palanquin got all the credit".

Conversion:

Begum Samru's conversion three years after Reinbhardt's death has baffled scholars. She was baptised to Catholic Church under the name of Joanna at Agra on 7th May, 1781 by a Carmelite monk. This Baptism elevated her from her undefined status to that of an accepted widow. According to John Lall,"The conversion may have appeared to her as a delayed solemnization of marriage and removal of the stigma of concubinage at a time when legal status had assumed greater importance." She used her changed faith to demand reprieve.

When in 1803 Lord Wellesley asked her to surrender her Jaidad she appealed for compassion on the basis of a common faith. However, except for observing some of the essential rituals of Christianity, she preserved the manners and customs of her social milieu and dressed herself in conventional Mughal style, her faithful huqqa constantly at hand. In life-style, personal appearance and activities Begum flaunted both-her Muslim as well as Christian identities. She regularly maintained the Mughal durbari etiquette in her court, conducted public business from behind a screen, apparently in defence to Muslim conventions.

Romantic Phase :

Begum Samru had everything that one could aspire for - power, wealth and fame. She had enchanting charm and had lost husband when she was heardly 28. She yearned for love.

Though she loved George Thomas, but was repelled by his brutish manners and low origins.

In 1790 she was swept off her feet by flamboyance of Frenchman, Le Vassoult. This romance proved to be her waterloo. Vassoult harboured animosity against George Thomas. This created factionalism in her army. The scandal rocked the Jaidad. The Emperor and her friends tried to warn the Begum about the consequences of this dalliance. It had no effect on her.

Vassoult indulged in the most uncavalier like intrigue. He was out to finish G. Thomas and poisoned ears of the Begum against him. In the midst of these intrigues in 1793, Father Gregorio solemnized in secret the marriage of the Begum to Vassoult.

12 years back the same monk had baptised her. Begum added 'Nobilis' to her Christian appellation and became 'Joanna Nobilis Somer'.

At the instigation of her new lover, the Begum set out to destroy G. Thomas and reached his headquarters at Tappal. This led to mutiny in her forces. She retreated and Sardhana was as good as lost. Two battalions marched to Delhi to offer allegiance to Zafaryab Khan, her half-witted step-son. Begum appealed to British for help (in 1795, March/April). Its terms and conditions were worked out.

She had agreed to retire to Patna.

Le Vassoult had alienated everyone including the peasantry in Sardhana through his arrogance. As mutinous soldiers were about to take Begum and her lover as captives, the two lovers decided to flee at midnight.

They signed a death pact in case of imminent danger of capture. In confusion, Vassoult shot himself dead.

The Begum was captured, humiliated and dragged to Sardhana by her own once loyal soldiers. Some say it was a trick played by G.

Thomas as the Begum wanted to get rid of Vassoult. The British had refused to accord legitimacy to Zafaryab Khan for different reasons. Desperate Begum Samru appealed to Thomas in desperation.

The man she had sought to destroy was now her only hope. Thomas gallantly put aside his past resentment.

He sought the help of Maratha chiefs and involved them in a complicated maneuver to extricate the Begum from her difficulties. Sardhana was restored back to her.

Anticipatory Diplomacy:

Maratha Chief Ambaji Ingle had designs on her Jaidad. The Begum moved briskly to demonstrate her capacity in the field, sounded out the Sikh Sardars as possible allies and once again enlisted Thomas's support. The British had their own problems with Marathas and the French.

By 1803 British plans were ready to take on Marathas and the French. Before launching the two-pronged attack in Deccan, they decided to get in touch with the Begum through Mir Muhd.

Jaffar of Bareilly, her most important confidante. Her dilemma was that she was deeply obliged to Mahadaji Scindia (d. 1794) for help from time to time.

Daulat Rao Scindia, Mahadji's successor was still the Peshwa's Regent and Bakshi of Moghul empire. But at the same time she could hardly resist the overtures of the British, the rising power.

The Begum tried to disarm British suspicions by peshbandi (anticipatory diplomacy). Initially, she sent troops to deccan to help Marathas. In the best Walter Reinhardt tradition-as British victory seemed imminent she shifted her troops to join the British.

It took her two years to rebuild relationship of trust with the British for this act. Lord Wellesley was all set to take over her Jaidad and accused her of hobnobbing with Holkar against them. Holkar, the Jat Raja of Bharatpur and the Sikhs played upon her fears, hoping she would join them to stall extension of British power. Begum had been on best of terms with the Sikhs. During emperor Shah Alam's time, she had prevailed upon the emperor to allow Sikhs to build nine Gurudwaras in Delhi, including Majnum Ka Tila. Though she facilitated the release of British Collector of Saharanpur, GD Guthrie from Sikhs, it only deepened British suspicions. Begum Samru was watching developments carefully.

The capture of Jat Deeg Fortress by the British in 1805, Maratha defeat and the friendship treaty between Maharaja Ranjit Singh and the British convinced her to opt for the British openly.

Recall of Lord Wellesley helped the Begum. The new Governor - General, Lord Cornwallis decided to leave her in "unmolested possession of her Jagir", but asked her to remain careful about people who helped anti-British elements.

The British had their own reasons to make peace with the Begum. They wanted to utilise her influence over principal Zamindars in North-West part of Doab and over the Chieftains and incursions of Sikhs to ensure tranquility. This paid them rich dividends. Begum Samru died in 1836.

Some scholars have compared the Begum to Ahilya Bai of Indore and Mamola Begum of Bhopal. The British Circles called her notorious but admired her. The natives said that she was born a politician, has allies everywhere, and friends nowhere.

Begum Samru has been the most outstanding among rulers of 18th/19th Century India.

Khirm, Sirhama - 1948

When a Dacoity looked like ‘Raiders’ attack

By Kuldeep Raina

SIRHAMA and Khirm are the two picturesque villages located on Bijbehara-Pahalgam road. Khirm is the last Kashmiri village, which opens above into Ashtadhar-Wularhama forests. While Khirm is one and a half km away from Sirhama, the latter is close to the main road and nine kms from the tehsil headquarters of Bijbehara.

Sirhama, derived from Suryahama has remained a great centre of Sun-Worship in by-gone times and also finds mention in the Amreshvar Mahatmya.

In 1948 there were eighteen Pandit families-all Bhats, who lived in Sirhama. There were just six Pandit families, Rainas and Bhats in Khirm. It was the first day of the moon-lit fortnight of Savan and the other day villagers were going to celebrate Idd. The impact of the raiders’ attack was still fresh in the minds of people, as raiders had been pushed across just three months back.

Attack:

In the evening, villagers had come out of their houses to look for the moon. A few Pandits had also joined them. Moon had been sighted, but suddenly the tranquility was disturbed by the shouts of Jia Lal, son of Thokur Bhat. He was trying to warn the villagers that the raiders had come. The villagers thought he was making fool of them. Soon the sound of a firing shot was also head. It was around 8 PM and darkness was gradually setting in.

The raiders’ had the reputation of looting and killing Kashmiri Pandits. When the first news of “raiders” reached Sirhama, Gh. Qadir Dar had come out with a lamp in his hand. He was going to invite the “raiders” to his home for dinner so as to give time to Pandits to flee. As the light of the lamp made the movement of “raiders” visible, the intruders got annoyed and fired at Gh Qadir. A bullet hit him in the abdomen and he collapsed down.

The family of late Sat Lal Bhat had a marriage function to be solemnized the following month. They had stocked everything for this purpose. After the firing shot was heard, the family shifted the women-folk to the house of a neighbour Ghani Nengroo. Sham Lal Bhat, son of late Sat Lal Bhat hid himself among the bhang bushes. His two brothers, Gopi Nath and Shamboo Nath accompanied other Pandits, who went to inform police. Mirza Afzal Beg, the Revenue Minister was also camping in Anantnag. After half an hour, the family managed to retrieve 4-5 boxes, containing valuables and hid these in the bushes.

Massacre:

Soon three more shots were heard. Sat Bhat, Raghav Bhat and Tarachand were closely related. Their houses formed sort of a single complex. These families were taking dinner. They used to keep bored-firearms to protect maize from bears. ‘Raiders’, numbering 10-15 in number forced their way into their houses. They called Sat Bhat, Tarachand and Raghav Bhat down and lined them up. Sat Bhat was shot in the temple. He died on spot. Raghav Bhat was injured in the thigh. Tarachand was lucky and received a mere kissing injury.

‘Raiders’ went to search all the Pandit houses in the locality. It took them three hours. Gold and double blankets (Jora Pachi) were special attractions for looters. Ladies handed over Tulsi, Talraz and Dejhoors. The ‘raiders’ broke upon the metal boxes to see if any money was hidden. A family had hidden silver coins in ash in a wok. This was taken away.

Raiders also thrashed few Muslims. When raiders entered the house of late Sat Lal Bhat, Razak Rather, the numberdar had tried to mislead them. He told them the house belonged to a Muslim family. Rather was thrashed by the raiders. Few pushthu-speaking villagers from the neighbouring Dodu were moving with the raiders and possibly helping in the identification.

The Muslim families had also fled from their homes. Only the brave ones had stayed behind. Injured Raghav had been taken by the villagers to the hospital in Bijbehara. The incident created tremendous fear among the villagers, who did not dare enter their houses again. When the raiders first reached Sirhama, they had tried to befriend local Muslims, telling them to save their lives. The killing of Qadir Dar was ample warning to Pandits that no one could save them.

Khirm:

From Sirhama the ‘raiders’ went to loot Khirm Pandits. The Pandits had taken dinner and gone to sleep. Mrs. Gopi Nath Raina, holding her 2½ year old son in her lap was still awake. There was a gentle knock at the door. It was Nand Lal. Before Mrs. Gopi Nath could respond, he left to knock at the door of Narayan Joo. Nandlal told Narayan Joo that raiders had reached Sirhama. He had gone to Sirhama to meet the Patwari. Nandlal added that the raiders had already killed two people in Sirhama and advised him to immediately shift the family somewhere. Naryanan Joo felt terribly disturbed. Nandlal also woke up other Pandit families. Sona Kak’s family escaped to the neighbouring Ashtadhar forests. Naryanan Joo’s family and others escaped to surrounding villages.

The ‘raiders’ fired a few more shots. Sona Kak’s two sons Amarnath and Dina Nath came down from the forest to find out what the firing was all about. When they reached home, they found two raiders’ standing guard at the main door of the house. Other ‘raiders’ had gone in to collect the loot. The raiders took Amarnath and Dina Nath as captives.

Meanwhile their brother Gopi Nath also reached home. He too was caught. Somehow Dina Nath managed to escape. After bringing the looted goods down, they packed these into bundles. They then went to loot other Pandits houses of the locality. Nidhan Bhat, son of Bhagwan Dass and Shavjee, son of Thokar Ram were also taken as hostages.

Gh. Mohd. Bhat was among the first to learn that raiders were likely to come to Khirm. His in-laws lived in Sirhama and they had intimated him. Gh. Mohd. decided to inform Pandits. Before he could reach Pandits' locality, the raiders caught hold of him. They asked him to show his house. He was a rich man. The ‘raiders’, information was accurate as they were guided by the Pushtu-speaking locals from Dodi. Gh. Mohd. led the raiders to some other house. As the raiders entered that house, Gh. Mohd. escaped.

The ‘Raiders’ loaded the looted goods on the shoulders of Amarnath, Gopinath, Nidhan Bhat and fled towards forest. The ‘raiders’ told Amarnath since he was a bachelor they would try to arrange a match for him. When raiders and the hostages had walked 8 kms, they decided to rest. Hasan Gujar, the tenant of Sona Kak lived here. The ‘raiders’ demanded food from him. ‘Raiders’ were four in number, while others were locals from Dodi. One of these locals was quit friendly to the hostages. They too decided to befriend him and requested him to help them escape. The local man from Dodi told them, “Sirhama Pandits have gone to inform the police. When the police will come, I will blow the whistle. You should run away then.”

Police Station:

Meanwhile Sirhama Pandit delegation met Mirza Afzal Beg and related what had happened. Gopi Nath, son of late Sat Lal Bhat was a good friend of the Revenue Minister. Mirza Beg told Pandits, “How is this possible that the raiders have descended on Sirhama. We have already pushed them back”. The Revenue Minister made them wait till 5 AM. Mirza Afzal Beg along with a big contingent of police left for Sirhama at 5 AM. Why the police was not sent immediately remains a mystery? Sirhama Pandits had met Mirza Beg at 9 PM. The police force under the leadership of SHO Prithvi Nath ‘doctor’ chased the ‘raiders’ right upto Gutli Bagh. The dacoits threw the looted goods into Sindh. One of the dacoits was reported killed. As soon as the police reinforcements reached the foot of Ashtadhar forest, the Dodi local whistled the hostages to run away. They freed themselves as the ‘raiders’ were deep asleep and began descending down through the short-routes.

When the hostages reached Herakhal, the local maidan, the whole Khirm had assembled to give them a grand reception. They embraced and fondled them in sheer joy. It looked like a festive occasion. The villagers accompanied the freed people to their homes.

Retrospection:

Earlier in the morning Dina Nath, son of Sona Kak (Khirm) had brought his family from Ashtadhar forests to home. A family member recalled, “It looked as if ghosts had descended down on our house. Clay and dust was all strewn around. The looters had broke open the boxes and made topsy-turvy of these. They had taken away everything”.

In Sirhama not only Pandit ladies had gone in hiding but the whole village had taken shelter in the neighbouring villages of Mahind, Nowshehr, Hogam and Wapzan.

As the dust settled down, people and the administrators began re-thinking on the entire episode. Was it a raiders’ attack or simply a dacoity committed under the guise of raiders? Surmises were made that the attack may have been the handiwork of some group of raiders, who may have stayed back. Others said the ‘raiders’ were from Gutlibagh, a village inhabited by Pathans. Some generations ago, few of these Pathans had come to Marhama (Dodi) and settled there. The two groups may have collaborated to commit a dacoity. As the raid was fresh in the public mind, the dacoits used it as a cover. Lastly the terrain was also favourable. Sirhama is the first entry point into the forest, while Khirm was the last village. In Kashmir myths and the history mingle too often.

Visiting Tulzapur - A dream come true

By Kuldeep Raina

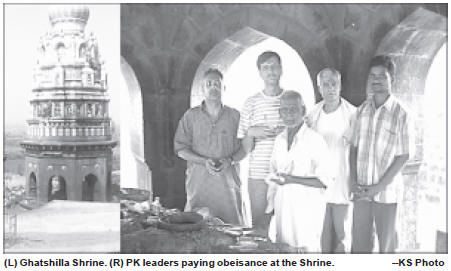

I am very greatful to Dr. B.A. Kathare, a senior dental surgeon at Dharashiv (Osmanabad), who hosted us during our stay at Dharashiv for informing me about the sacred of Tulzapur and Ghatshilla.

The sacred shrine of Tulza Bhagwati is located at Tulzapur, 25 kms from Dharashiv. As per local folklore the goddess is consort of Lord Shiva. The place where shrine is located is the place where the Goddess appeared to Shivaji Maharaj and presented divine sword to fight the Mughals. Tulzapur is considered to be ‘Puranpeeth’, the other two Puranpeeths being - Renuka Mata at Mahur in Nanded district and Mahalaxmipeeth in Kolhapur. Sapt Shrungi Devi shrine in Vani district (Nasik) is regarded as Adha Shaktipeeth

Another place near Tulzapur is Ghatshila - the place where Tulza Bhawani told Lord Rama the way through which Ravana abducted Sita. The Shila on which Lord Rama stood while listening to the Goddess still stands.

Lakhs of devotees visit Tulzapur shrine on the day of Navratra, walking bare feet hundreds of kms. The shrine is managed by 16 families of non-Brahman Maratha Purohits, called in popular parlance Kadams. The Purohits are not forbidden from taking meat. 'Bali' is done at Tulzapur as per Shakhta tradition. The tradition seems so similar to ours in Kashmir.

It was great honour for us to be allowed to visit the shrine at the time when Tulza Bhawani gets ready for Abhishek. The 16 Purohits asked us to make a presentation on rise of terrorism in Kashmir. They assured full solidarity with Displaced Kashmiri Hindus.

Veer Munshi relocates his Exile

by Kuldeep Raina

Exile is a profound tragedy. Those who do not experience it cannot feel its pain. It shatters the victim. Fear, Displacement, Marginalisation, continued Genocide, Rootlessness, Alienation, Social disintegration, deculturation all accompany genocide.

Exile is a profound tragedy. Those who do not experience it cannot feel its pain. It shatters the victim. Fear, Displacement, Marginalisation, continued Genocide, Rootlessness, Alienation, Social disintegration, deculturation all accompany genocide.

There are two responses from the civil society of the victimised community. Sensitive sections give meaning to the exile, regenerate the community and prepare it for retrieving what has been lost. Hedonist segment advocates accepting exile as a fait accompli and to justify the compromises invents its own politics based either on betrayal or incomprehension. One cannot be neutral to one's own genocide and destiny. In responding to genocide the victim does not have an option of remaining 'objective', of course he can be rational.

His strong commitment to fight genocide is the key to his survival. An artist has to survive as well. In a milieu where the victim's politics does not fall in 'political correctness' an artist, a creative one, has a greater challenge i.e. to combine sheer commercialism with intellectual concern to maintain visibility on the genocide.

Veer Munshi, a famed painter, who was displaced from Kashmir alongwith other members of his community in 1990, has shown how a responsible artist can serve the twin concerns - addressing the genocide and perpetual exile, besides the larger commitment to the issues faced by the minorities all over the world and the victims of unjust wars (waged either for ideology or for imperialist expansion).

Minorities have been victims of the same phenomenon - religious intolerance and cultural/ethnic exclusivism.

Erosion of the state, where the state is either unable to defend the minority or is apathetic, too has contributed to the marginalisation of minorities, displaced as a result of ethniccleansing.

In his first exhibition in early nineties, Veer Mushi's focus was - the process and the tragedy of displacement of his owncommunity.

It has been a long journey since then. Munshi has witnessed the helplessness of the people in New York, in London, in West Asia, and in Mumbai.

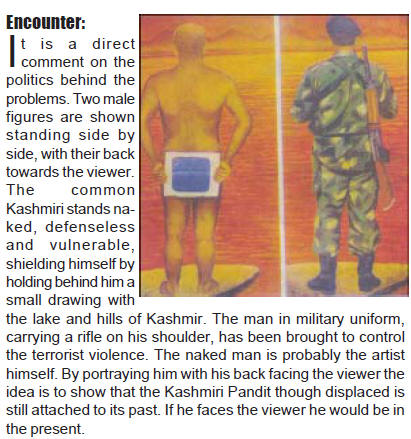

His latest exhibition titled 'Encounter' - jointly promoted by Art Alive Gallery and the Visual Arts Gallery, was on display at India Habitat Centre on 25-30 August. He describes his journey from 'focus on personal genocide' to 'larger genocide of peoples' affected by terrorism' as hiscommitment to social responsibility.

He attributes his sensitivity to the experience of his own history. Munshi asks the people to remain vigilant.

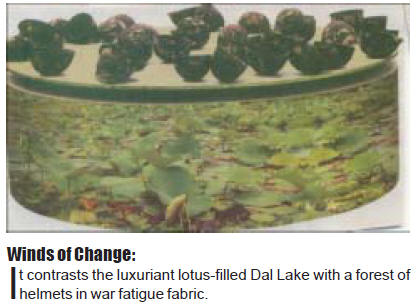

Munshi's works on display combine three themes: Division - ideological, political. Belief and identity divide the communities, Partition - which is the geopolitics of this divisionin the Indian subcontinent, West Asia and elsewhere, Migration - is the fallout of partition where millions of refugees are battling the marginalisation and rootlessness. Munshi has used the river to show the divide because it evokes nostalgia. It is a metaphor for territorial division.

He comments that 'Division' is a malaise threatening the ordinary citizens in every country.

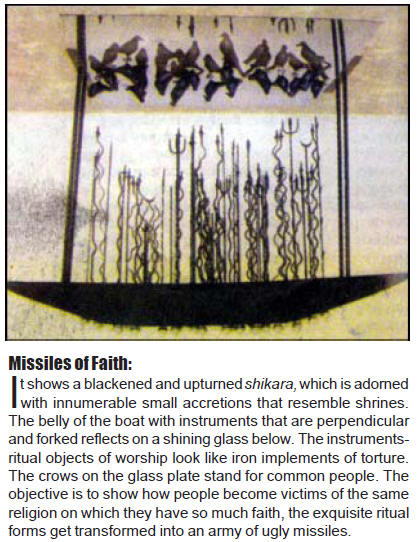

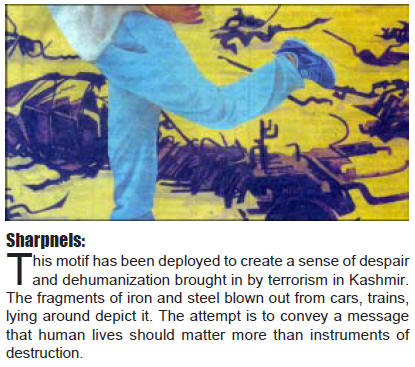

Silence of weaver: Shikara, here as in Missiles of Faith, has been used as a meaningful metaphor not to remind us of Kashmir's beautiful Lakes but to transport the viewer across the shores to death and destruction. Here a Shikara is hung up and laid to rest on a wall.

It is adorned with profile of AK- 47 to convey that the beautiful paradise now lived under constant fear of terrorism.

Partition Eye To Eye: Two men crouch on either of the border

Dialogue: Two large dogs confront each other across the border.

Gandhi vs Gandhi: It is shown that only Gandhi was against the partition.

The divide in each is shown with a river. The river is shown as symbol of divide because it invokes nostalgia.

Will there Redemption of Peace: It shows a huge wooden drum with a flock of white pigeons.

Below the circumference is the face of a Kashmiri, middle-aged braving unfriendly weather but who still retains hope.

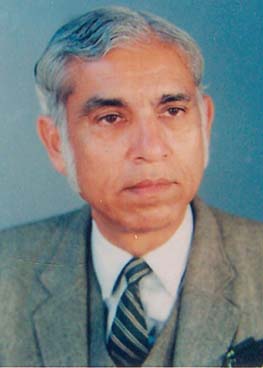

Dr. B. N. Sharga

The Living Kalhan

By Kuldeep Raina

Lucknow, the home of Dr. Baikunth Nath Sharga holds key to Kashmir’s past. Two centuries back many families from Kashmir, among Kashmiri Pandits, Shia Muslims and Bhands-the folk theatre performers, moved to Lucknow and made it their permanent home.

Lucknow, the home of Dr. Baikunth Nath Sharga holds key to Kashmir’s past. Two centuries back many families from Kashmir, among Kashmiri Pandits, Shia Muslims and Bhands-the folk theatre performers, moved to Lucknow and made it their permanent home.

The first arrivals came to Lucknow in 1775 when Nawab Asif-ud-Daula shifted his seat of power from Faizabad to Lucknow. They settled down in a locality which later came to be known as Kashmiri Mohalla, which still exists in the old city.

Kashmiri Muslims:

The Kashmiri Shia came to Lucknow from Kashmir on the invitation of Hakim Mehndi who was the Prime Minster in the court of nawabs of Oudh. They were mostly his relatives or closely known to him. These Shia families belonged to Zadibal quarter of Srinagar. In Lucknow they started living in Maqbara Alia, a locality that still exist in the Golaganj ward of the old city.

These Shia families who trace their ancestry to Syed Shah Hamadan, an Iranian Sufi, assign different reasons for their migration to Lucknow. Shahin Abidi says her ancestors had come to Lucknow at the invitation of the royal family of Avadh. Others believe that their forefathers came to the seat of nawabs to preach Islam. Mr. Sadiq Ali, a leading businessman and PDP leader has also written on this theme.

Interestingly, a prominent Kashmiri Muslim who came to settle at Lucknow after 1947, was Jafar Ali Khan ‘Asar’. He was minister of Education in J&K during the reign of Maharaja Hari Singh. Jafar Ali was a renowned Urdu poet. He has authored many books. He settled down in Kashmiri Mohalla. Rais Aga founded the Kashmiri Young Association.

Another group of Kashmiri Muslims who moved to Lucknow during the period of Nawabs was that of Kashmiri Bhands – folk theatre performers. The first group of Bhands reached Lucknow in 1795 when Nawab Asif ud Daula (1775-1797) invited them to entertain his royal guests on the occasion of the marriage of his son Wazir Ali. They settled down in the localities Shahganj and Pir Bukhara (old Lucknow). The last performing Kashmiri Muslim Bhand in Lucknow was Jahangir. He lived in Shahganj. UP Sangeet Natak Academy was kind enough to provide him a regular stipend. He died a few years back.

(2)

Kashmiri Pandits :

In Lucknow, Lahore, Allahabad, Agra and Delhi major diasporas of Kashmiri Pandits came up. Kashmiri Mohalla of Lucknow, which at one time formed half of the old city, rose just a few decades after Kashmiri Mohalla of Delhi (Bazaar Sita Ram). This mohalla has been home to leading Pandit luminaries – Pt. Brij Narain Chakbast, Pt. Ratan Nath Dar Sarshar, Pt Bishen Narain Dar, Pt. Tribhuvan Nath Sapru ‘Hijr’, Pt. Sheo Narain Bahar, Pt.Daya Shanker Kaul ‘Naseem’, Pt.Shyam Narain Masaldan, etc.

About Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula (1775-1798) it used to be said:

“To whom God does not give,

To him gives Asaf-ud-daula.”

The generosity and catholicity of Asaf-ud-daula saw influx of talented Kashmiri Pandits into Lucknow, resulting in the birth of Kashmiri Mohalla. Oudh was ideally suited to Kashmiri Pandits.It was a centre of political power in northern India, and the Nawabs were known for their liberal cultural patronage. Moreover, it lay close to Delhi, where the seat of Imperial Mughals was located.

Dr. Baikunth Nath Sharga :

Dr. Baikunth Nath Sharga is a scion of the distinguished clan of Kaul-Shargas, who were Wasikedar of the Oudh Court. In 1775, Nawab Asaf-ud-daula, after the death of his father ,Nawab Shuja-ud-daula, shifted the seat of government to Lucknow from Faizabad. Dr Sharga’s ancestors –Pt. Laxmi Narain Kaul and Pt. Niranjan Das Kaul had moved to Oudh during the rule of nawab Shuja-ud-daula (1753-1775). Faizabad was the seat of the provincial government. The two brothers had joined the Shahi Fauj as company commanders. Pleased with their ability, Nawab’s wife Begum Ammat-uz-zohra granted the two brothers a royal Wasiqa ( a sort of hereditary pension) in 1813. It was after receiving the royal recognition in the form of Wasiqa that the Kaul brothers added ‘SHARGA’ to their surname Kaul.

SHARGA:

‘Sharga’ in Persian means Horse. Probably, the ancestors of Dr Sharga served in the cavalry division of the Shahi Fauj. This, however, does not explain why only Kaul family among others serving in the cavalry division should keep the appellation Sharga.

Dr. B N Sharga is himself seeking answers for Sharga in the Mongolian desertlands. In Mongolia “Shar” means Yellow, “Sharga”-Yellowish. Sharga is quite common for indicating colour of animals: horse, goats, etc. There are several meanings for Sharga in Mongolia. A low land valley as big as 50 km. x 70 km. In the middle of Altai range is called by the name of ‘Shargun Gobi’ or Desert of Sharga. There is also an administrative unit called ‘Sharga Soum’(county) of Gobi Altai aimag. Also, an ethnic group, that came to Sharga is known by the name Sharga. These people shifted to Sharga

(3)

valley some 300 years ago from the contemporary Uyghur Autonomous region of China, where Jungar-the west Mongolian Kingdom was situated before its collapse. Some surnames are of Central Asian/Afghan origin – Jalali, Bamzai, Durrani, Jawnsher, etc. It is even possible that the Kaul clan carried nick name of Sharga even when they were in the valley. After migration they may have dropped it for sometime only to re-adopt it later. Salman Rushdie in his latest novel Shalimar the clown has immortalized Shargas by adopting it among his main characters.

Ancestry:

Dr.B N Sharga’s earliest known ancestor is Pt. Narain Kaul (1640-1712). He belonged to Dattatreye Kaul family of Rainawari, Srinagar. His son Pt. Zind Ram Kaul came to Delhi during the times of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb (1658-1707). He was an outstanding scholar of Sanskrit and Persian. His fighting abilities helped him get a good job in the Mughal imperial army. Pt Zind Ram Kaul and his family lived in Bazaar Sita Ram. His son, Sahib Ram Kaul, inherited the qualities of his father-proficiency in Sanskrit and Persian and soldiering. He too served in the Mughal Army. Sahib Kaul’s sons Pt. Laxmi Narain Kaul and Pt. Niranjan Das Kaul moved to Oudh and then to Lucknow. Initially, the Kauls lived in Rani Katra area of Lucknow.

Pt. Laxmi Narain Kaul Sharga had three sons Prem Narain, Sheo Prasad and Durga Prasad (b.1797). Pt. Durga Prasad Sharga excelled as a scholar of Urdu, Persian and Arabic language and was employed in the Oudh court as a Mushirkar. In May 1856, he was one of the members of the delegation that accompanied Malka Aliya, when the later called on Queen Victoria to pray for restoration of the throne of Oudh to Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, the last king of Oudh. The British punished Pt. Durga Prasad by withholding the payment of Wasiqa to him from 1857 to 1859. His Jagirs were also confiscated. Durga Prasad died in 1870.

Pt. Durga Prasad had three sons – Bansi Dhar, Sri Krishna and Bishambhar Nath. Pt. Bansi Dhar worked as Bakshi (pay master) in the Shahi Fauj of Nawab Amjad Ali Shah (1842-47). After the British annexed Oudh and disbaned Shahi Fauj, Pt. Bansi Dhar lost his job. His only son was Pt. Baij Nath Sharga (B.1850).

Pt. Baij Nath Sharga first became a Sharistedar in the Farukhabad district during the British rule and later, on the recommendation of his father-in-law Dewan Moti Lal Atal of Jaipur, he was appointed as the Nazim of Ganga Nagar and lived in Naveli, Sawai Madhopur (Rajasthan). In a palace intrigue, hatched by local chieftains, Pt. Baij Nath was poisoned to death in 1890 at the young age of 40 years. A few years before his death perhaps in 1883, he built a big haveli in Kashmiri Mohalla.

Dewan Moti Lal Atal’s (1821-1893) daughter Radhika Rani was married to Pt. Baij Nath Sharga. The grand daughter of Kishan Lal Atal, Dewan’s son was Kamla Nehru, wife of India’s first Prime Minister.

Pt. Baij Nath Sharga had two sons namely Brijendra Nath Sharga and Shyam Manohar Nath Sharga (b. 1879). Pt. Shyam Manohar Nath Sharga was a linguist of repute and had great command over Hindi, English, Urdu and Persian language. Holding M.A. degree in English literature in 1901, he was appointed Professor of English literature in 1902 in

(4)

Canning College. Pt. Shyam Manohar Nath Sharga did LL.B from Allahabad University in 1904 and joined the Bar. Later he joined as Munsif in 1908, finally retiring as the District and Sessions Judge in 1934. Pt. Shyam Manohar was victimized by the British for his close association with Dr. Annie Besant, Pt. Moti Lal Nehru and Pt. Bishambhar Nath sahib. The British subsequently appreciatd his integrity and made him the Chief judge of Udaipur state in 1934 and conferred the title of Rai Bahadur on him in 1935.

Pt. Shyam Manohar Nath Sharga was a poet too. He had two sons Manharan Nath and Kailash Nath.The younger son of Pt. Shyam Manohar, Kailash Nath was born in 1914. Pt.Kailash Nath passed M.A.(English) and LL.B in 1937 and qualified the PCS (judicial).

As there was no vacany for the post of Munsif , Pt. Kailash Nath started his legal practice. It was after independence that G B Pant, the first chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, appointed him as a Judicial officer in 1947. He retired as A.D.M (J) in 1975. The noted film maker Muzaffar Ali shot some scenes on him for his documentary film, The Wasiqadars of Oudh.

Pt. Kailash Nath Sharga was married to Rajwanti (Raj Kumari) daughter of Pt. Rameshwar Nath Dar of Kanpur, in 1934. Pt. Kailash Nath had four sons – Baikunth Nath, Amrit Nath, Arjun and Vinay. His two daughters Saroj (married to Pt. Shyam Mohan Dar of Mandsaur,M.P.) and Sita (married to Kamal Zutshi of Nagpur) are married in Kashmiri families. Pt Kailash Nath passed away in 1991 while his wife Rajwanti Sharga died in 2004.

Dr. B.N. Sharga:

Dr.Baikunth Nath Sharga was born on 21st December,1938.He had his early education from Parker Inter College, Moradabad and college education from Govt.Jubilee Inter College and Shia Degree College, Lucknow. He passed B.Sc in 1959.Later, he did his M.Sc (1962) and Ph.D (1967) in Chemistry from Lucknow University. He taught Chemistry at his alma mater, Shia Degree College (1967-1994). As a Reader in Chemistry, he taught at Shia Post Graduate College (1994-1999).

Theatre

Dr Sharga has also been involved in the theatre movement. He has so far produced over 400 plays, which have been shown in different parts of the nation. Since 1965, Dr Sharga has been involved in different roles in the theatre – actor, director, producer, etc. The themes of his plays have been varied –social, mythological, comedies, etc. Dr Sharga is an institution builder. More than 100 new artistes had begun their carrer in Sharga’s plays. Some of these artistes are now working in films, TV serials. Dr Sharga has remained President, Panchsheel Kala Mandir (1970-73), President, Sanket Theatre Group (1973--),Vice-president Avadh Cultural Club (1976-1980), Member Lucknow Film Association.

Dr Sharga is a prolific writer having published over 400 articles in different periodicals. Besides over 4000 ‘Letters to the Editor’ to his credit. American Biographical Institute, North Carolina, selected him for the ‘Man of the Year’ award in 1998. Dr Sir Tej Bahadur

(5)

Sapru Memorial trust, Allahabad, honoured him with a Silver plaque and a citation in 2004. Besides this Dr Sharga has remained General Secretary, Yuvak Bharti (1973-76), Vice-president, World Association of World’s Federalists (1970-73), General Secretary, Lucknow University Associated Colleges Teachers’ Association (LUACTA) 1973-76.

As a proud Kashmiri Pandit Dr Sharga has been taking keen interest in the welfare of the community. He has remained President, Lucknow Kashmiri Association (1996-99) and senior vice –president, AIKS (1997-2000). His role during the past 15 years and more towards the displaced Pandit community has remained unique, identifying totally with the exiled community.

Dr Sharga’s magnum opus “Kashmiri Panditon Ke Anmol Ratna”, six volumes of which already stand published, has assured a place for him in History. Kashmiri Pandit community (whether old Kashmiri families or ‘Taza Koshur’ newly migrated families from the Valley) have remained indifferent to the task of preserving their history-achievements or saga of continued persecution.

This pains a sensitive man like Dr B.N. Sharga. He undertook the challenging task of recording and preserving the history of families, which have brought pride to India. In this effort some of the families remained indifferent while some others cooperated to an extent. His effort has been a solo endeavour. He has been spending his meager savings in accessing material and publishing his research work. At times many make fun of his work. But that is the way how all great people in history have managed to do great things.

Dr. Sharga’s work and scholarship has made him immortal. He has worked out his own methodology to reach out to the families for recording their family history. At times, he has to face embarrassing questions.

Next time when Dr. Sharga asks for your ‘Vanshavali’ (genealogy) don’t hesitate to co-operate with him because he is the living Kalhan of our times. He preserves your history for posterity. We wish him good luck and a long healthy life.

Pt. Amar Nath Muthoo: A Tribute to Grandfather

By Kuldeep Raina

PT. AMAR NATH MUTHOO, affectionately called by family members as 'Lala' lived at Bulbul Lankar (Ali Kadal) in downtown Srinagar. He was born to Pt. Damodar Muthoo and Smt. Vishmal.

Pt. Amarnath Muthoo in early years of his service at Anantnag

Amar Nath had one brother-Pt. Shankar Nath and three sisters, married in Budgami, Taploo and Rangroo families. He was married to Kamla alias Kakni, daughter of Pt. Amarchand Tikoo of Peth Kanihama.

Amar Nath was serving as SHO Kulgam in July, 1947 when he was promoted and transferred to Askardu as SHO with the rank of Sub-Inspector. His two close relations-brother Shankar Nath and wife's brother Sh. Gopi Nath Tiku too served in State Police. The former remained constable only while the latter retired as SHO.

Pt. Amar Nath was a man of great taste and lived in style. He loved Bacchus and quite often held Sufiana mehfils at his place. His aristorcratic style of living and the authority he wielded earned for him the sobriquet of 'Hakim Sab'. My grandfather (Nana) enjoyed close friendship with Pt. Dina Nath alias 'Dina Patel' and Kh. Saifuddin, who later retired as DIG. Sometime before grandfather had served at Muzaffarabad also. There was a group clash. He had slapped one of the trouble makers who was quite sick. Though the latter died a natural death, yet a case was slapped against Pt. Amar Nath. An enquiry was ordered, DIG Kashmir was to visit Muzaffarabad in this connection. 'Dina Patel' was Traffic Inspector in Muzaffarabad. Amar Nath asked for help from his friend 'Dina Patel'. The day DIG left for Muzaffarabad Patel manoeuvred to stop traffic at Domel bridge. DIG could not come for enquiry. Meanwhile, Amar Nath was able to convince the aggrieved family that victim had died a natural death. The matter was subsequently closed.

Amar Nath had six daughters but no son. He reared his children like boys, keeping male names for them. His brother's wife had died young, leaving behind a son and daughter. It was on Lala's insistence that the son Kashi Nath was sent to college. He subsequently joined Army, retiring as Major.

How my grandfather was killed has remained a mystery to the family. Shortly before his death he wrote identical letters to his brother and Sh. Gopi Nath Tiku. In these he had written, 'I am under siege. It is difficult to survive. If I live I will manage to reach home whatever difficult the terrain might be'. He had also impressed upon his brother that his daughters should be made to eat food in the Thali (plate) in which he used to take his food. Amarnath's eldest daughter in 1947 was 12 years old, while the youngest was only 6 months. Amar Nath had also written, 'my wife likes Kahwa. She should not have to worry about Sugar. Keep it in plenty for her'. Through the letters the family came to know that things were bad in Askardu but at the same time Lala was safe.

Amar Nath as SHO Askardu had the responsibility to take care of treasury at the Fort. It is said Pakistanis were looking for namesake of my grandfather who was probably treasury officer. As per one version grandfather was dragged, nails were thrust into his body and he was mercilessly killed. Another version claims that Amar Nath was abducted and held captive. It is said that he later subsequently started his business in Askardu. Amar Nath was just 34 in 1948.

My grandmother Kakni could never come out of shock. Going to Pirs and Faqirs became a daily routine. She would sit often at the window of brerkani (attic) and mutter to herself 'ya yim nata nim' (Either come or take me also). One day when Labroo family in the neighbourhood had called Nandbab to their home Kakni also went there. The occasion was safe return of Pt. Sham Lal Labroo who too was held captive in Muzaffarabad. When Kakni bowed before Nandbab he gave her two-rupee note. It was unusual and was interpreted as hint to her not to come again. 6 months later she died.

Soon after grandfather's martyrdom Kothi Bagh Police Station had received a wireless message from Col. PN Kak about his death. It was through Pt. Amar Nath Taploo (sister's husband) the family learnt about the killing. Grandfather's close friend Kh. Saifuddin helped the family sort out Insurance claim within no time. Amar Nath's six daughters were brought up under the affectionate care of Sh. Shankar Nath and Sh. Gopi Nath Tiku.

Dr GS Muju - A Successful Entrepreneur

By Kuldeep Raina

Kashmiri Pandits have excelled in academics, professions, managerial skills etc. But entrepreneurship has never been their forte. Dr. Gouri Shankar Muju, a Kashmiri Pandit by descent and a leading industrialist in Mumbai, has belied this myth. His success story-from a brilliant academician to a successful entrepreneurs, has written a new chapter for Pandit excellence in entrepreneurship as well.

Kashmiri Pandits have excelled in academics, professions, managerial skills etc. But entrepreneurship has never been their forte. Dr. Gouri Shankar Muju, a Kashmiri Pandit by descent and a leading industrialist in Mumbai, has belied this myth. His success story-from a brilliant academician to a successful entrepreneurs, has written a new chapter for Pandit excellence in entrepreneurship as well.

Born in 1938, Dr. Gouri Shankar Mujoo hails from Brekujan (Lower Sathu) quarter of old Srinagar city. As most of the Kashmiri surnames are nicknames the family lore says Mujoos are originally Rainas. Some members of the extended Mujoo family prefer to write Raina in place of Mujoo.

Rainas' traditional home has been Rainawari, a suburb on the outskirts of Srinagar city. As per the family story Dr. G.S. Muju's grandfather's grandfather bid adieu to Rainawari soon after a devastating fire incident in the suburb and the family had to seek shelter in Lower Sathu area. An anecdotal story that has survived says that the ancestor of this clan while fleeing on his horse reached a garden. He felt thirsty but could not find any water to quench his thirst. A lady vegetable-seller offered him a reddish in place of water. The people who were witness to the scene nicknamed clan's ancestor as Mujoo. That is how Rainas transformed into Mujoos. Many clans of Pandits have similar stories to tell, some of which still remain shrouded in mystery. Before 1990 displacement Mujoo clans had been living in Rainawari (Kalwal Mohalla), Lower Sathu and Raghunath Mandir mohallas.

Dr. G.S. Muju's father Pt. Jia Lal was a small official in J&K State's Electrical Department, retiring as Head Clerk. Though only under Matric he was extremely proficient in English and had good grasp of intricacies of grammar. Dr. Muju's grandfather, Pt. Manji Muju, was a high official in Maharaja Pratap Singh's court. Extremely handsome, Pt. Manji wielded good influence at the Court and lived in style.

Early years of Dr. Muju were spent in the idyllic town of Baramulla in north Kashmir. He had his schooling at home under the care of a governess. Shortly before the Valley was attacked by Pathan Tribal hordes Dr. Muju's grandfather died and the family shifted to Srinagar.

Dr. Muju studied for 9th and 10th class at National High School, Srinagar and joined SP College in 1951. He passed FSc. in 1953 and went to study at DAV College, Kanpur for his B.Sc.

Soon after passing B.Sc. in 1956 he joined as an analytical chemist at BI Drug company. His Chief Chemist, Mr Sachdeva motivated him to go for higher studies in the same field. In 1959 Dr. Muju got admission in the renowned Braunchweig Technical University and sailed to Germany in December 1959. Dr. Muju credits his elder brother Pt. Jagar Nath Muju for giving encouragement to pursue higher studies.

He had to encounter two problems-language and resources to pursue higher studies. Courses at all levels were taught in German language. Through Minister of Post Dr. Muju got job in a German company 'Koeln-Kalk'Chemical Company. It manufactured fertilisers. Dr Muju was taken as analytical chemist. He learnt German language well and saved enough to finance his higher studies. He served in this company till 1962.

Dr. Muju has pleasant memories of working at 'Koeln-Kalk'. Visiting down memory lane he recalls, "The atmosphere was very friendly here. The staff was very helpful. I was accepted part of the society, may be my fair complexion facilitated it. One day the Managing Director of the Company, a German enquired in half-broken English 'why I was getting paler by the day'. He rang up the health unit of the factory, which recommended my admission in the Hospital. I remain grateful to them for the care they extended to me during my sojourn in the hospital. They helped me every way. The staff members still have connectivity with me".

Germany had recovered from the scars of IInd World War and Nazism. Though people admired Hitler (for building Otto Bahn and for Volkswagen), yet they never expressed it publicly.

In 1962 Dr. Muju joined Braunschweig Technical University to pursue Haupt (Main) Diploma, a degree which equalled MSc. The first year of the Diploma was equivalent of 11th Class. Since Indian B.Sc. was not recognised in Germany he had to start afresh. His teachers at the University were big names in their respective fields. They included Prof. Hartmann (Inorganic Chemistry, Dr. Carios (Physical Chemistry), Prof. Inn Hoffen organic chemistry etc. The latter had made his mark internationally when he became pioneer to produce margarine (artificial butter), fortified with Vitamin D. Till then such an entity was unknown. In the Haupt Diploma Course Dr. Muju's subject was Sugar Technology. His Head of the Department was Prof. Schneider, an internationally known Sugar Technologist.

D. Muju is all praise for the education system prevalent in Germany and for the teaching staff which taught there. He praises academic freedom and charming examination system, free from regimentation. Selection for the teaching faculty was very, perfect and so vigorous that no professor could get admission for his ward in the respective university. Teachers had not only to be academically brilliant and good in teaching but had also to be innovative. Once selected they were very powerful and would had their way. Favouritism was never accepted.

For D. Phill higher merit in Haupt Diploma was mandatory. Even before Dr. Muju finished his Haupt Diploma he received a clearance letter from theFranzens University, Innsbruck, Austria to pursue D.Phil in the field of Organic and Pharmaceutical Chemistry. The University bears distinction of producing five Noble Laureates in the field of Physics, Chemistry, Economics etc. Dr. Muju was awarded the scholarship by the Ministry of Science and Research, Vienna, Govt. of Austria for the entire period of his research work. He joined Franzens University in 1972, Completing D.Phil in less than five years in 1976.

Dr. Muju's guides were Prof. Bretschneider and Prof. W.Kloetzer. Dr. Muju's research work was based in creating such new molecule which could have some bearing on medicinal values. These molecules were subjected to various tests to investigate its effectiveness at one of the world's finest Pharmaceutical Company - Hoffmann-La Roche, Switzerland. These investigations when completed take more than 15 years of rigorous efforts. Dr. Muju worked on synthesis of Sulphonamides, anticancer drugs, anti-TB drugs etc.

Dr. Muju had been fortunate to having worked in the R&D Laboratory of Biochemic, Kundl, Austria, in the field of cephalosporins in general and Cephalexin in particular. This product is next generation of Pennicillines.Biochemic was the first to have developed and produced world's first penicillin tablets, under the supervision of Dr. Brandl.

Dr. Muju describes Prof. H.Bretschneider his major guide and discoverer of Madribion-the long-acting sulfa, as a fantastic person. When he completed his doctorate Prof. Bretschneider in a moving gesture told Dr. Muju, "Please never leave me".

In November 1976 Dr. Muju was selected as Pool Officer in CSIR and shifted to India. Dr. Muju's hopes of pursuing an academic career were cut short when Poona University's ICL did not select him for Lecturer's post despite his high academic qualifications. The Lecturer's post also carried little remuneration of Rs 500 per month. Dr. Muju left CSIR to join as Chief Research Executive in Chemopharma (Somani Group of Industries) on monthly salary of Rs 2500.

In 1982 Dr. Muju established a partnership company under the name ofRibopham Laboratories at Dombivali, Thane District, Maharashtra. The manufacturing plant was set up in 1984 and the production started in 1985. His immediate efforts went into R&D and production of an anti-TB Drug (Pyrazinamide) post the establishment. He challenged himself into marketing of many product lines to have edge, competitive both on price points and quality. Dr. Muju's initial success saw the company introduce themselves into many other product lines catering to market demand strategy thus making Ribopham Laboratories' market reputation headway in getting larger volume deals from companies like Nicholas Piramal India Ltd. (India), Yash Pharma Ltd. (Mumbai), Paks. Trade Ltd. (Hyderabad), Dharamsi Morarji Chemicals Ltd. (Mumbai), etc. currently Ribopham Laboratories is engaged in the manufacturing of a range of Antioxidant products. They also specialise in Perfumery products. Dr. Muju's concern has been involved in producing raw material and Bulk drug for anti-diarrhoels (Tindazole, Metronidazole) and Veterinary drugs (intermediate only) like RoXarone.

Ribopham Labs has been in manufacturing for over two decades now and has an annual turnover of more than Rs 1.5 crores. In a lighter vein Dr. Muju says that he went for Chemistry just by default and had aspired to pursue a career in Medicine.

Married to Saroj Dhar who hails from a middle class Pandit family of Gundi Ahlamar (Nai Sarak), Srinagar Dr. GS Muju is a complete family man. Despite his heavy schedule he finds time to attend to small problems of carpenting, plumbing etc. at home. He also loves to cook. Mrs. Saroj Dhar, who has her Masters in Economic and additional B. Lib., had a stint in Indian Airlines.

Shy-looking Mujus shun publicity and are quite modest. Recently, they were in Jammu town while on way to Srinagar, both to revive their memories and re-discover their roots at the place of their birth and also among their community brethren. Dr. G.S. Muju has never gone to Kashmir after 1953 while Mrs. Saroj had last seen Kashmir in 1958.

Dr. H. Kumar Kaul - A Living Legend on Yoga

By Kuldeep Raina

Allama Iqbal once told Prem Bhatia, the veteran journalist", Had our ancestors not migrated from Kashmir, Pt. Moti Lal Nehru would have been a district-level pleader and I would have been a district-level poet". Kashmiris have risen to great eminence only when they decided to bid adieu to their homeland. This holds true of Dr. H. Kumar Kaul too. His contributions to the study and practice of Yoga have made him a sort of leg. A dynamic personality, Dr Kaul has distinguished himself as a fine educationist, seasoned administrator and a celebrated Yoga practitioner. Presently, he is Director of Gandhi Arya Sen Secondary School, Barnala (Punjab). His only lament is 'my own community does not know me'.

Kashmiri Pandits do not invest in property. They invest in education of their children. Dr Kaul's parents too gave him quality education. Born on 26th July, 1938 at Srinagar, Dr. H.Kumar Kaul had his early education at Kashmir's best school, Tyndal Biscoe School. Later, he joined Govt. Amar Singh College. It was here he distinguished himself as the Best Swimmer, Best Debator, Best Sportsman and Best Actor. He was adjudged 'All Round Best'. It was in 1959 that Dr Kaul, a college student then, caught the attention of veteran film actor, Prithvi Raj Kapoor. The doyen of Indian Cinema felt impressed with his role in stage play “Chattan”.

Dr. Kaul did his M.A. in English literature with distinction and B.Ed. from University of Kashmir. He had his diploma in journalism from Delhi University. He did his Doctorate from Punjabi University, Patiala. His dissertation was "Contribution of the Deras and Akharas of Punjab in Yoga and Sufism". He was the first scholar in northern India to venture in this particular field.

Early sixties were bad times for Kashmiri Pandit community. The policy of communal discrimination in state services made many brilliant Pandit boys leave Kashmir to seek living outside J&K. Dr. H.Kumar Kaul had also to move to Abohar (Punjab) in 1963. He headed Department of English for ten years at DAV College here. He made his mark not only as a gifted teacher but excelled in cultural and literary fields too. Dr. Kaul edited 'The Seemant Jyoti'for a decade. For a while he assumed Principleship of DAV College, Karnal.

1975 proved to be a challenge for him. SD College, Barnala had fallen out of reputation. Student indiscipline in the proceeding sessions had created a climate of insecurity and uncertainty. Dr. H. Kumar Kaul was asked to head this institution to steer it out of its troubles. His hardwork, tact and visionary ideas helped the institution to regain its reputation. The college once again became an institution of academic excellence. Dr Kaul continued to head this institution till his retirement in 1992, displaying his worth as an academician and administrator. During this period, he was a member of Punjab University Syndicate and Academic Council. After retirement, he has remained associated with the administration of SD Educational Institutions.

It is in the field of Yoga, that Dr. H.Kumar Kaul's name is taken with awe and respect. His deep knowledge of the practice of Yoga has made him a leg. Yoga is a way of life to him. He has written more than 220 research papers on Yoga, which have been published in reputed newspapers and magazines in India and abroad. As a practitioner of Yoga, he has authored 8 Text-books, besides 54 books. These have been widely-acclaimed. Inpeccable prose and remarkable communication skills have helped Dr. Kaul to make his message reach wider audience. The great scholar of Yoga has also given practical demonstration of nearly 100 yogasanas in different competitions. He has also given numerous Radio-talks over AIR and BBC on Yoga therapy.

The thrust and emphasis of his books is on bling the traditional and modern approachs in Yogic philosophy and science, keeping in view the existing socio-economic milieu. Presently, he is working on Yoga and Islam, besidesContribution of Punjab in Hathayoga. Dr Kaul was introduced to Yoga at the age of 11. He learnt Yoga through its great practitioners - Swami Neelkanth, Swami Laxman and Swami Krishnand, General Secretary of Divine Life Society. As an Indian, he feels proud of its great past and locates Yoga in Hindu Scriptures. In Ramayana, he finds Hanuman as a true Yogi. who could control his mind and senses by practice and Vairagya (renunciation). Dr. Kaul observes: "Hanuman practised Hathyoga (Yoga of Hand) and is a living symbol of Vairagya. That is why his aim was to attain perfection which he could not attain so much in Rama, but in Rama's citashakti i.e. Sita. Hanuman's search for Sita is nothing but his spiritual quest".

About Gita, Dr. Kaul remarks: "All the 18 chapters in the Gita are designated as the types of Yoga...All the eighteen Yogas contained in the 18 chapters may be reduced to four-the Karma Yoga (the Yoga of action), the raja yoga(the Yoga of super-consciousness), the bhakti yoga (the Yoga of devotion) and the jnana yoga (the Yoga of knowledge). Tradition holds that spiritual life begins with Karma Yoga and goes on evolving into the other three respectively".