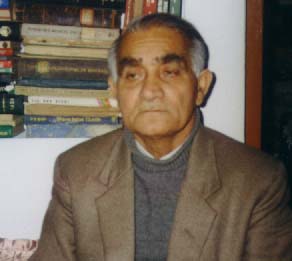

Brij Premi

A Genius in his Art

Every one who knows Urdu knew Dr. Brij Premi. He was a genius in his art. His contribution to the fund of Urdu literature and historiography on Kashmir is well-recognized. Dr. Premi enjoyed high status in the field of Urdu literature at the sub-continental level. He was a highly cultured person, possessed great literary taste and scholars liked to interact with him. Abu Syed Qureshi, well-known Urdu scholar and Manto’s friend said of him: "Premi’s love is immortal. I highly appreciate Premi’s firmness of mind and inquisitiveness, his interest and love."

Dr. Brij Premi was a multidimensional scholar and served Urdu literature with dedication. He excelled in all genres----short story writing, literary criticism, research etc. He wrote beautiful prose, and avoided being prolix. Dr. Premi’s language was lucid, simple and focussed at the average reader. He disliked use of too many Persian words in Urdu vocabularly, which made it unintelligible to the common people. His usage was always appropriate, suited to the requirement of the situation. He did not have to labour for words. These came spontaneously and effortlessly. His elegance in writing kept the reader glued to it. Imagery in his prose was superb. He gives graphic description, at times relating even the minutest detail and literally transports the reader to the locale\situation he is describing. This is true of his essays as of his travelogues. At the same time there is no element of exaggeration in this. He was down to earth in his writing.

Dr. Brij Premi was a patriot par excellence. He had deep commitment to the welfare of the downtrodden people. Early in his life he came under the influence of Pandit Prem Nath Pardesi, a great litterateur who subscribed to progressive views. Cultural Front played a vanguard role in heralding a renaissance movement in Kashmiri literature. Dr. Premi was influenced by it and also contributed to it. He held Left views and has left for posterity two outstanding works ------A literary biography of Prem Nath Pardesi and history of Progressive Writers’ Movement in Kashmir. These two seminal works have a permanent place as rich source material for undertaking comprehensive assessment of the Left movement in Kashmir. His progressive ideology brought him in close contact with big names in progressive Urdu literature----Krishan Chander, Ahmed Nadeem Qasimi, Abu Syed Qurieshi, Salam Machli Shahri, Ali Sardar Jafri, Khwaja Ahmed Abbas, Jan Nissar Akhter Dr. Qamar Rais, Prof. Mohd. Hassan, etc. Dr. Premi was also influenced by social realism of Munshi Prem Chand.

Though Dr. Premi contributed much to historiography of Kashmir, his authentic and pioneering work on Saadat Hasan Manto has no rival. There is mounting evidence on how counterfeit academics continue to plagiarize Premi’s researches on the great short story writer. Premi was as much influenced by Manto’s social radicalism as by his display of pride in his Kashmiri origins.

Dr. Brij Premi loved Kashmir and was deeply rooted in its spiritual and historical tradition. His excellent work on Kashmir’s patron saint-poetess Lalleshwari, on Pir Pandit Padshah, Martand Ruins and admiration for Shams Faqir, the great Sufiana poet, indicate this. His love for Kashmir was not contrived but natural. He delved deep in to Kashmir’s past to keep it alive in the present. His patriotism and catholicity in outlook were outcome of this.

It is a great moment for Kashmir Sentinel, an institution committed to renaissance task, to bring out a commemorative number, to honour the memory of this great son of Kashmir and Kashmiri Pandit community. Our special thanks go to Dr. Premi Romani, illustrious son of late Dr. Brij Premi , who worked overtime to get writings of his father translated in time for the issue and also extended cooperation as and when required. We also express our gratitude to Prof. ML Koul, Prof. RK Aima,Prof. HL Misri , Sh. Predhuman K. Joseph K. Dhar, Prof. ML Raina, Sh. MN Kak, Sh. Upender Ambardar. They are distinguished academicians in their respective fields. It was with the spirit of labour of love that they undertook the difficult task of translation work. Lastly, we thank our guest writers who contributed to this thematic number.

Featured Collections

Brij Premi-My Father

By Avinash Aima

My thoughts go back to the days, when my father used to go every morning for a walk in the company of my mother in Naseem Bagh, an area surrounded by lofty Chinars. He not only enjoyed the fragrance of cool air, but also turned these beautiful mornings into occasions of literary interactions. Such luminaries - Prof. Rais Ahmed, Mrs. Shakhti Rais, Prof. Shakeel-ur-Rehman, Prof. Manzoor-ul-Islam, Mrs. Manzoor, Prof. Ayub Khan and others, who lived in the Campus quarters at Hazratbal would also be on their morning walk jaunts. On return, Dr Premi would enlighten his family members about the discussions he had with these people.

I also recall how our house at Ali Kadal used to host literary meets. These meetings were attended by scholars - Hakim Manzoor, Moti Lal Saqi, Makhmoor Badakhshi, JL Raina, Pushkar Nath, Rehman Rahi, Arun Kaul, Ghulam Nabi Baba, Wajhi Ahmed Andrabi etc. The meetings continued well past midnight. I too happened to sit in these gatherings but without any interest. My father, after day's business, would meet scores of friends at Habbakadal, conversations would drag on for hours together. My father would also make me attend many poetic symposia and 'shows' in the Tagore Hall,Srinagar.

Once Krishan Chander and his wife Salma Siddique visited Srinagar. My father, an admirer of Krishan Chander met him and discussions on literary aspects continued for many days. Saadat Hassan Manto also came up during the discussions. My father was those days engaged in research work on Manto. The meetings which my father had with Krishan Chander later flowered into a companionship. My father wrote down a memoir based on these interactions. It hasn't been published as yet.

Prof. Shakeel-ur-Rehman had close association with Dr. Brij Premi. He seemed impressed with my father's talent and literary interests. I can still recollect the discussions he held on the cultural heritage of India with my father Prof. Shakeel was that time engaged in writing a book titled 'Ghalib Aur Hind Mughal Jamaliyat' Dr. Shakeel's scholarship left deep impact on my father, it helped him to identify other areas of literature and pursue these with vigour. On my father's death, Prof. Shakeel said, “I have lost an intimate companion of my life and feel weaker in his absence”.

Though my father was deeply fascinated by Urdu and considered it as the real vehicle of his expression, yet he did write few stories in Kashmiri and some articles in English.

In his Kashmiri short stories, he projected psychological and social dimensions of the society. For example, in the story 'Vudav', the protagonist, a female character, while being caught in the whirlpool of disturbed environment, gets obsessed with certain spiritual urges which need to be filled. In 'Pas Az Gadai Chakri', he paints the picture of an employee, burdened by economic misery. The character is exasperated with the situation he lives in. He has to spend his meagre earnings to fend off the debts, which leaves him little to tide over his existence for the month. He gets visual hallucinations - seeing his creditors waiting for money with tilted noses on the currency notes. The writings portray the psychological trauma of these econmically marginalised people. Dr. Premi presents artistically the difficulties poor employees underwent in supporting large families. 'Chaye Geit' is a stream of thoughts, which have been woven in the warp and woof of realism.

'Kashmiriyaat', the social, literary and historical aspects of Kashmir, was very dear to him. Mr. Suraj Saraf, has acknowledged this in an essay on him. Mr. Mohd. Yusuf Teng, in his forward to 'Jalwa-i-Sadrang' says that Brij Premi, after ploughing through thousands of pages of available material, has presented various aspects of Literary, Historical and Social heritage ofKashmir in a capsule form, in an unbiased way. About the same book Prof. Hamidi Kashmiri observes that it would add new dimensions to research.

Dr. Premi's book 'Kashmir Ke Mazameen' awarded posthumously by J&KCultural Academy (1991) is dedicated to Kashmir. He says, "I dedicate this book to my native land. If through these writings, if somebody feels my presence I would feel delighted and pleased. The essays have the fragrance of the soil of my land".

Born in a tradition-bound Kashmiri Pandit family, Brij Premi (1935-1990) loved to read in his early years the adventure novels in the late hours. His father, Pt. Sham Lal Aima, a writer of repute, wrote short stories, which were published regularly in the Daily Martand. My grandfather had given an impressive performance, when Pt. Nehru visited the Basic Model School, Srinagar. He rubbed shoulders with such eminent personalities - Kashyap Bandhu, Prem Nath Pardesi, Master Zind Kaul, Fazil Kashmiri, Nand Lal Talib, Dina Nath Warikoo, Dina Nath Mast, Aftab Koul Wanchoo etc. This provided a good ambience for my father to become a writer. Pt. Sham Lal Aima also excelled in writing allegories and pen-sketches.

My father, in his early years, wrote under the pseudonym 'Yugdeep', to voice his protest against the social evils. His articles appeared in 'Martand', 'Navjeevan', 'Jyoti' etc.

His death was deeply mourned by writers and artists. They sympathised with us in our hour of grief:

Ahmed Nadeem Qasimi (Lahore, Pakistan) puts it as:

"Sad demise of Dr. Brij Premi has left me deeply shocked. Brij Premi was young, but some health problem has removed him from us".

Upender Nath Ashk (Allahabad) says,

"I knew he was diabetic, but this disease is quite common these days and people can live with it for 80/85 years in many cases. But it is also true that death keeps no calender and who can avoid what has to happen. He had still many projects to complete".

Prof. Ale Ahmed Saroor (Aligarh) says:

"The service rendered by Dr. Brij Premi in the teaching and criticism of Urdu language and literature has a specific place. His book on Manto goes a long way in understanding and analysing this great artist".

Prof. Jagan Nath Azad (Jammu)

"When I was in Europe, I came to know about the sad demise of my dear friend. I was deeply shocked at his demise".

Prof. Qamar Rais (Delhi)

"I cannot express the feelings of dejection my mind is filled with at the sudden passing away of my dear friend, Brij Premi. He had a passion for Urdu literature".

Prof. Shamim Hanfi (Delhi)

"I felt very sad at the tragedy of passing away of Brij Premi. Whenever I would visit Srinagar, I would meet him. He was a cultured and polite person. I would always get pleasure in meeting him".

*The author is son of Dr. Brij Premi. At present he is working as Principal of Camp Higher Secondary School at Muthi, Jammu.

Beacon light of Kashmir Literature – Dr. Brij Premi

By Aseer Kishtwari

Besides being “Heaven on the Earth”, the beautiful Valley of Kashmir has proved a fertile soil for giving birth to a number of great writers, critics, poets, historians, researchers, artists, intellectuals, politicians, religious beacon lights and lovers of art, culture and languages. When one goes through the pages of the literary history of Kashmir, it becomes difficult to choose the greatest man of letters. On the basis of his marvellous contribution towards Kashmir literature , Dr. Brij Premi for his attachment with Kashmir and literature on Kashmir can be easily compared with the literary luminaries like Dr.Sheikh Mohd. Iqbal, Brij Narayan Chakbast, Rattan Nath Sarshar, Tribhuwan Nath Hijar, Anand Narian Mulla, Ramanand Sagar, Kashmiri Lal Zakir, Prem Nath Pardesi, Prem Nath Dhar, Shamim Ahmed Shamin, Mohd, Yousuf Taing, Mohd-ud-Din Fouq and Dr. Ghulam Mohi-ud-Din Sofi etc.. Dr.Brij Premi, who passed away in 1990 is known for his short stories, authoritative work on Saadat Hassan Mantoo and research papers relating to history, geography, art, culture, languages and literature of Kashmir – his motherland.

During the long years of his life from 1949 to 1990 (A.D.) Dr. Brij Premi has contributed as many as twelve good books written in Urdu and Kashmiri languages and some more compilations are yet to see the light. A good number of his english articles, published in “Kashmir Today” of the J&K Information Department are being compiled and published by his dedicated son Dr. Premi Romani, who has surprisingly brought out six books of his great father, on his own initiative. For his excellent literary works, Dr. Brij Premi deserves to be called the “Pride of Kashmir Literature” because genius people like him are rarely found in modern Kashmir. Dr. Premi is no more but his writings have made him immortal. The coming generations will continue to remember him, till his treasure of literature is preserved for reading. I have not seen Dr.Premi with my own eyes but the photographs published in his books show him more intelligent, handsome and sharp than his sons especially Dr. Premi Romani. On the eve of 16th death anniversary of Dr.Premi I ventured to pen down a few lines in remembrance of the “ Pride of Kashmir Literature“ who breathed his last on April 20, 1990 in Jammu – soon after mass migration of Kashmiri Pandits in that year.

Dr. Brij Premi was basically a short story writer in Urdu, who started his literary career with his first short story “AQA” (The Lord) which was published in “Amar Jyoti Srinagar” in the year 1949 A.D. “Harif-e-Justujoo” was published in 1982, which became his first publication, containing innovative research cum critical articles on Prem Nath Pardesi and other prominent short story writers of Urdu. His second book titled – “Jalwah-e-SadRang”came out in 1985 which was forewarded by the well known writer and researcher, Mohd Yousuf Taing. While complimenting Dr. Premi, Taing has said that after famous historian Mohd-ud-Din Fouq, Dr.Premi was the first Kashmiri writer who introduced socio-cultural heritage of Kashmir among the world community. Thus it is clear that Dr.Premi has beautifully and successfully highlighted the Kashmir culture in his aforementioned book.

“Saadat Hassan Mantoo-Hayat Aur Karnamay” – published in 1986 – compelled writers like Professor Mohd. Hassan, former Head of the Urdu Department of Delhi University to comment that it was a landmark work on Mantoo which needed no further additions and alterations. It was on the basis of this book that Dr.Premi was accepted as an authority on Mantoo, in the Indian sub-continent and Pakistan. “Zauq-e-Nazar”, a collection of Urdu articles was published in 1987, in which un-touched aspects of Urdu literature have been artistically explained by the author. Two more books of Dr.Premi –“Shajer Kari” and “Murgbani”, specially written for promotion of adult education got also published in 1987, whereas another of his literary masterpiece “Chand Tehrirain” (A few writings) came out in 1988. This book carries a travelogue, some “Nusri-Marsiyae” (Elegy in prose) on Sheikh Mohd. Abdullah, Prem Nath Bazaz, Kashyap Bandhu, Kuldeep Rana, Som Nath Sadhu etc.. etc.. and articles like Khawaja Mohd Abbas Aur Film, Sadat Hussan Mantoo Aur Film, Upinder Nath Ashq Aur Film, Rajinder Singh Bedi Aur Hindustani-Film, Hindustani Filmoon Key Chand Manzaleen, Devmalayee Kahanyan on Ramayana and Mahabharata and other research articles.

Another well known publication of Dr.Premi – “Kashmir, Kay Mazameen”essays on Kashmir containing informative and well-knit articles on the civilization, culture and scenery of Kashmir Valley, came out in lime light in 1989 as was forewarded by Dr.Hamidi Kashmiri, former Vice–Chancellor of Kashmir University. Dr.Hamidi has appreciated the book with an open heart by calling its author as the second “Fouq” of Kashmir literature. Likewise–“Jammu-wa-Kashmir Mein Urdu Adab Kay Nashunuma”, duly forewarded by PadamShree Moti Lal Saqi came out to the market in 1992. In view of its demand, Dr.Premi Romani, the compilor, had to bring out three consecutive editions of this important book on development of Urdu literature in the J&K State. Despite of having a voluminous book of Professor Abdul Qadir Sarwari on the subject, the compilation of Dr.Premi was highly liked by the lovers of Urdu language & literature for its better comprehension and easy language.

Shri Moti Lal Saqi had prepared a monograph of “Samad Mir” a legend in Kashmiri literature and Urdu translation of the said monograph as made by Dr.Premi, was published by the Sahitya Academy, New Delhi in 1992. Yet another publication of Dr. Premi – Mantoo Katha” was brought out by Dr.Premi Romani in 1994 in which some beautiful and important articles on Saadat Hassan Mantoo have been incorporated for the benefit of the general readers. “Sapnoon Key Sham”, published in 1995, is a collection of Urdu short stories of Dr.Premi. In his foreward prominent Urdu writers Kashmiri Lal Zakir has rightly said that these short stories were worth reading as the essence of realities of social life have been expressed in a befitting manner. The famous short stories in the said book are – “Lumhoon Key Rakh”, “Hansi Key Mout”, Sapnoon Key Sham”, “Mayray Bache Key Salgirah”, “Ujri Baharoon Kay Ujray Phool”, “Manasbal Jub Sookh Gaya” etc.. The book titled “MUBAHIS” ( The Discussions), published in 1997 among other articles also contains an interesting article – “Lumhay Jou Zinda Hain”which is infact a historical interview of Dr.Premi with Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah, on the history, culture, literature and political aspects of Jammu & Kashmir.

“Vatsney” (The critical Appraisal) and “Virasat” (The Heritage) are the only two Kashmiri books of Dr.Premi, published by his learned son in 1999 and 2000 respectively. The former book carries articles on the life and literary works of Ghalib, Abul Kalam Azad, Prem Nath Pardesi, Munshi Prem Chand, Bahadur Shah Zafar etc.. whereas Dr.Premi’s Kashmiri short stories and other Urdu write-ups have been incorporated in the latter book. The unpublished matter lying with Dr. Premi Romani includes – “Prem Nath Sadhu – Ahad, Shakhsiat Aur Funkar”, “Prem Chand Ek Nayee Jehat”,numerous articles written in Urdu and English languages and 350 letters of the late writer written by him to his friends, contemporary writers and fans of Urdu and Kashmiri literature right from 1949 to 1990. Credit goes to Dr.Premi Romani for publishing and preserving the literary works of his illustrious father. He has yet to work hard and publish the remaining valuable works as well. It is in this backdrop that all the living writers aspire to have a son like Dr. Romani, who understands the importance of his late father and works with full dedication in publishing the hidden literary treasure left behind by the departed soul.

My good wishes are always with him.

*The author is a prominent and prolific writer, historian, researcher and poet of the J&K State. He has published many books. “Focus on J&K” written in English is a comprehensive work on the updated socio-cultural history of the J&K State. Mr. Aseer is presently working as Director Audit & Inspections and Deputy Director Accounts & Treasuries, Jammu. He is the President of J&K Urdu Forum and General Secretary of Rasa Javidani Memorial Literary Society Jammu.

Remembering a friend and former colleague

by A.N. Dhar

Dr. Brij Premi is no more with us today, which is a painful thing for he was a writer of tremendous potential and, at the same time, a man of solid achievement. Death snatched him away from us in the year 1990 when he was 55 years old. A dear friend and colleague of mine in the University of Kashmir, I held him in esteem for his wonderful qualities of head and heart. Human and affectionate to the core, he always kept his cool and spoke words of wisdom as a man of learning whenever the occasion demanded. Temperamentally, he shied away from publicity and was a man of few words. Through my occasional conversations with him I found him widely read and very knowledgeable. He was indeed a gentle colossus-judging him on the basis of his literary achievement and the manuscripts he actually left behind unpublished.

"

Dr. Brij Premi shot into prominence and became a celebrity in the Urdu literary world across the Indian subcontinent with the publication of his outstanding book on Sadat Hasan Manto, based on his doctoral thesis on the eminent writer. The volume has been hailed as a land-mark-acclaimed as the best piece of critical writing on the creative work of Manto as a writer of short stories in Urdu.

Dr. Premi Romani has performed the duty of a proud son in bringing out the memorial volume titled "Brij Premi Shaksiyat Aur Fun" that includes numerous critical essays contributed by a host of scholars on Dr. Premi and his work. For accomplishing such a task, he has won accolades from his father's friends, fellow-writers and admirers. Another volume titled "Varaasat" includes, Dr. Premi's two short stories in Kashmiri, three Kashmiri prose essays, his Kashmiri translations of some of Manto's short stories and eight critical estimates of Premi's Kashmir volume“Vechnai” contributed by celebrated Kashmir writers including Akhtar Mohi-ud-Din, Amin Kamil, Moti Lal Saqi and others. For bringing out this volume too, Dr. Romani has been highly praised and felicited by many scholars and writers. On going through the two volumes, I got convinced that Dr. Brij Premi will continue to be remembered as an outstanding scholar of Urdu who would have scaled still further heights if he hadn't died prematurely.

It needs to be mentioned here that Dr. Brij Premi came up as a scholar and writer the hardway. He had to face economic hardships in pursing his educational career. It was long after he secured a first class in M.A. (Urdu) that equipped additionally with a doctoral degree he began his teaching career at an advanced level in the Urdu department of the University of Kashmir. Judging by what Dr. Brij Premi achieved as a writer while he lived and the writings he actually left behind unpublished, there is no doubt that his contribution to scholarship, research and creative writing has been formidable and memorable. So does his son, Dr Premi Romani, deserve kudos for what he has done to glorify the memory of his noble and talented father.

Finally, on going through some of Dr. Premi's writings in Urdu and Kashmiri, I realized what a valuable service he has rendered in writing on Urdu writers in Kashmiri and on Kashmiri writers in Urdu—achieving thereby a cross-fertilization in the realm of letters. I have also been impressed by the flow of his writing in Urdu as well as Kashmiri-I mean the effortless ease with which he writes. And this quality is matched by the lucidity of his style. His use of Kashmiri is specially impressive in as much as he writes with natural ease and keeps to the common Kashmiri idiom, not burdening his writing with words borrowed from Urdu or Persian. I greatly enjoyed reading his Urdu piece, “Main Yahan Rahtaa Huun”. It chows how rooted he is in the Valley of Kashmir, his homeland, and how proud he feels of his rich cultural heritage as a Kashmiri. The other piece that I would like to mention here is "Vada Yus Na Poora Gav". It is a reflective piece of writing that shows Dr. Brij Premi's skill in handling Kashmir prose. Writing the present note has sharpened my desire and curiosity to read more and more of the beloved writer and friend I had the privilege of having as my colleague at the University of Kashmir during more than a decade of the last century.

Premi - My Friend and Comrade

By C.L. Chrangoo

Dr. Brij Premi was an Urdu scholar par excellence. Cruel hands of death snatched him soon after his displacement from Srinagar in 1990. This came as a shock to his family, comrades, friends and above all the literary world of Urdu.

He held Marxist views, yet at the same time he was liberal in his outlook and demeanour. The cultural movement of fifties stimulated him to experiment with poetry writing. Soon he left it to take up prose. His grasp of the language turned him into a brilliant writer. His writings began to be published in reputed Urdu journals of northern India. This brought him closer to leading lumanaries of Urdu language in the country.

Brij Kishen Aima used to write under the penname of ‘Premi’. The style of his writing was bewitching. His elegant prose, marked by short sentences and rich themes, impressed his friends.

He rose up the ladder in his career the hard way. He had lost his father at an early age and had to shoulder the responsiblity of the family. Dr. Premi worked very hard and displayed determination in facing up to the situation.

Dr. Premi submitted an excellent work on Saadat Hasan Manto to earn his Ph.D degree. This brought fame to Premi Ji and opened new vistas in his career. He left behind career in school teaching to join Kashmir University as a Postgraduate teacher. It was here that he made his great contribution to Urdu language and emerged as a scholar of repute.

I was lucky enough to have enjoyed his companionship at many levels - as a collegue, as a friend and also as a comrade. My memories go back to the times when we were comrades in the Teachers Trade Union Movement. I would just recall one instance.

We happened to sit on a dharna at Badiyar during teachers’ strike in 1969. The call had been given by Teachers Association of J&K, then affiliated to Democratic Conference, a leftist outfit. As active comrades we had to listen to the long speech of Ram Pyara Saraf the preceding night. Messers Krishan Dev Sethi and Ghulam Mohd Malik were also there. We were issued directions by them. Myself and Dr. Premi had to sit on hunger strike at Badiyar under a shamiana, pitched just on the roadside. As the hunger strike was in progress, one of the Srinagar-based leaders of Democratic Conference came and called me in a manner which invited suspicion. He told me that Srinagar wing of Democratic Conference did not contribute to the decision to sit on hunger strike. He argued, “We are not with it. It is like asking alms from a government which we do not recognise at all. Our objective is to achieve the brotherhood of people all over the world from Soviet Union to China.” He went on to give me a long lecture on the dangerous goal that he and his likeminded collegues had embarked upon. This came to be called, “Peking via Pindi” thesis. I returned to the tent and conveyed in hushed tones to Dr. Premi what the Democratic Conference leader had said. Though shocked on learning this, Dr. Premi just laughed it away saying he expected this response. He, however, stressed that one should remain firm in conviction. I was highly impressed by Dr. Premi’s response and the strength of his conviction.

We sat through the day for hunger strike. For rejecting the ‘Peking via Pindi thesis’, we were dubbed as ‘Pandit communists’. Dr. Premi had clear mind and displayed boldness in day to day life.

*The author is an eminent educationist and was actively associated with Kashmir's Theatre Movement

Brij Premi - A Tireless Scholar

By Deepak Budki

Urdu literature is indeed indebted to writers like Mir, Ghalib, Iqbal, Prem Chand, Mantoo and Bedi for their creative and original writings but one cannot undermine the contributions of critics and research scholars like Altaf Hussain Hali, Ehtesham Hussain, Aal-e- Ahmed Saroor, Qamar Rais and the like for exploring the worlds of these writers in depth and preparing the common mind to appreciate them. One such scholar is Dr. Brij Premi who despite meager resources at his disposal explored the intricate world of Manto, a doyen of Urdu fiction . In fact, it took Premi almost a decade to collect data about Saadat Hassan Manto from different parts of the Sub-continent where Manto had either stayed for a short time or lived for a longer duration, especially from across the border i.e. Pakistan where Manto had ultimately migrated at the time of partition never to return to the land he loved the most, viz Bombay, now rechristened as Mumbai. Brij Premi set out to explore the virgin world of Manto at a time when Urdu, Iqbal and Manto had become an anathema in India. The boldness, promiscuity and notoriety attached to Manto, the D H Lawrence of Urdu Literature, had invited the ire of self styled purists in both India and Pakistan.

Urdu literature is indeed indebted to writers like Mir, Ghalib, Iqbal, Prem Chand, Mantoo and Bedi for their creative and original writings but one cannot undermine the contributions of critics and research scholars like Altaf Hussain Hali, Ehtesham Hussain, Aal-e- Ahmed Saroor, Qamar Rais and the like for exploring the worlds of these writers in depth and preparing the common mind to appreciate them. One such scholar is Dr. Brij Premi who despite meager resources at his disposal explored the intricate world of Manto, a doyen of Urdu fiction . In fact, it took Premi almost a decade to collect data about Saadat Hassan Manto from different parts of the Sub-continent where Manto had either stayed for a short time or lived for a longer duration, especially from across the border i.e. Pakistan where Manto had ultimately migrated at the time of partition never to return to the land he loved the most, viz Bombay, now rechristened as Mumbai. Brij Premi set out to explore the virgin world of Manto at a time when Urdu, Iqbal and Manto had become an anathema in India. The boldness, promiscuity and notoriety attached to Manto, the D H Lawrence of Urdu Literature, had invited the ire of self styled purists in both India and Pakistan.

Brij Krishen Aima was born in a lower middle class family in Kashmir Valley. He lost his father at an early age and had to support his family when he was just fourteen. He joined the Boy-service in the State Deptt. of Education after giving up his education. As a teacher, he suffered as a result of transfers from one village to another. His first pay packet was a meager sum of thirty rupees. Under such circumstances it was but natural that he should join the bandwagon of Progressive writers who were very active at that time.

His first short story “Aqa” (The Master) was published in ‘the Amarjyoti’,Srinagar. Thereafter his stories appeared one after the other in a number of newspapers and magazines within and without the state of Jammu and Kashmir. He adopted the pen name of ‘Brij Premi’ and established himself as a short story writer in the valley. He writes about himself, "My literary life as a short-story writer started in the middle of twentieth century. More often than not I used to pour out the pain and anguish of my soul into my stories. Even now whenever my inner agony makes me restless , a story is born. In fact, short-story writing is my first love (Harfe Just-ajoo)."

Brij Premi’s inner world was no different from the outer world in which he was constrained to live. The peasants, the labourers and the artisans of Kashmir were continuously being exploited by landlords and the capitalists, and consequently rendered poor, starved and penniless. The sub-human conditions in which his brethren lived haunted him day and night and hence he used his pen to depict their plight. He drew inspiration from Prem Nath Pardesi, another progressive writer who was popularly known as ‘the Prem Chand of Kashmir’. Apart from Pardesi, Brij Premi was influenced by the great romanticist, Krishen Chander, who had an emotional attachment with J&K State and used to describe its natural beauty in mesmerizing narrative in his short-stories . Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi too had influenced Brij Premi’s style to some extent. Notwithstanding, the writer who most influenced Brij Premi in his later life was the bespectacled, Liquor–addict workhorse known as Saadat Hassan Manto. The latter had such an impact on his mind that he devoted his rest of life to undertake extensive research on Manto . Premi not only wrote ‘Saadat Hassan Manto-Life and works’ and ‘Manto Katha’ but also conducted research on several writers of J&K State besides other historical and literary topics. Alas, the cruel jaws of death snatched him away at a time when he was at his productive best.

While talking of Brij Premi I must acknowledge the dedication and devotion of his worthy son Dr. Premi Romani towards his illustrious father. I came to know Dr.Brij Premi through his son only when I was beginning to enter the ‘Make believe world of Literature’ from that of ‘Matter of the fact world of Science’. Romani having noticed my flair for calligraphy asked me to write the final copies of his father’s thesis .We used to sit till late in the night in his house at Ali Kadal, Brij Premi used to give the corrected copy of his thesis which I used to write legibly. However I could not keep my promise to the end due to some personal compulsions and wrote about sixty percent of the thesis only. Later Romani himself completed the rest. However, at the end, I decorated the thesis by drawing caricatures of Manto at the beginning of each chapter. My joy knew no bounds when only after 2-3 months I came to know that Brij Premi had been awarded the Doctorate by the Univesity of Kashmir. Having come to know Brij Premi so closely, I found him an unassuming, soft spoken and a thorough gentleman who had devoted a life time to Urdu literature and Kashmir History. He would not, however, display his knowledge by talking about it every where which was a distinct sign of his humility. He was simple in his life style, coy and modest and showed no signs of promiscuousness commonly attributed to the poets and prose writers.

Abdul Ghani Sheikh writes about Dr. Brij Premi, “Krishen Chander and Manto have a vivid influence on the thought and style of Premi. His choice of words and felicity of his diction are superlative”. I do not, however, entirely agree with AG Sheikh. It is true that Brij Premi spent his life time on Manto and his works and one can see the latter’s influence on Premi’s writing in later part of his life but fact remains that most of the short stories written by Premi had been penned down much before Manto had made any impact on his mind. Though Premi wanted to write stories based on psychology and human behaviour in the footsteps of Manto yet his own gentlemanliness and lack of exposure to what Manto called ‘Sewers of society’ became a stumbling block for him. There were no brothels to visit in Kashmir, no Saugandhis or Sultanas to keep him company nor were there any Babu Gopi Naths to sacrifice everything for these forlorn castaways. Pushkar Nath, a well-known writer from Kashmir comments, “Those days Manto started dominating the literary scene and slowly Brij Premi got attracted towards him. Though he could not write exactly like Manto since he did not have a similar environment as Manto was beset in, yet he absorbed and assimilated each and every word of Manto and ultimately it all fructified in the form of his thesis ‘Sa’adat Hassan Manto Life and Works’.

‘Sapnoon Ki Sham’, a collection of short stories written by Dr.Brij Premi contains sixteen short stories. Most of them are written against the backdrop of beautiful lush green fields of Kashmir surrounded by blue snow- capped mountains but poverty and exploitation which resulted in pestilence and consumption ultimately take over and expose the delicate moth-eaten fabric of the society. In “Mansbal Jab Sookh Gaya” (When Manasbal Dried), a helpless mentally delinquent servant stakes his life to protect the property of his master. In ‘Larazte Aansoo’ (Trembling Tears), a man seeking transfer on account of unhygienic conditions is asked by his boss to send his daughter which enrages him and turns him into a Socialist. “Hansi Ki Maut” (Death of a Smile) is a story of brave educated and hardworking lady who struggles all her life to support her unemployed husband and the child. ‘Bahte Nasoor’ (Festering Sores) comprises three short short-stories or what we now call Mini stories. In the first, Prakash seduces his girl friend and later sells her in Bombay red light area. In the second, a father loses his son for mere four annas which he could not afford. In the third story two friends are compared, one who has acquired riches while the other still remains a pauper.

‘Nanhi Kahanyan’ (possibly the word was coined to mean Mini Stories)comprises two short short- stories. In the first the exploitation of police is exposed while in the second a master kills his servant for not supplying him his wife. ‘Ujhri Baharoon Ke Ujhre Phool’ (The Withered Flowers of Wasted Spring) is a story revealed by a madman who loses his wife and child as a result of unemployment and consequent penury and finds his dreams shattered . In ‘Yaad’ (The Memories) the narrator keeps watching the oarsman while crossing a river. The Oarsman is lost in his thoughts trying to recollect his love-affair in youth. ‘Sharnarthi’ (The Refugee) is a story of a refugee who has lost his father defending his village and is himself crushed mercilessly by a richman under his car. Surprisingly, the richman is not booked by the police. ‘Chilman Ke Sayoon Mein’ (Behind the curtain) is based on fetishism and has a distinct imprint of Manto in its treatment. ‘Aansoon ke Deep’ (The Tearful Farewell) is a story of a mother saying goodbye to a dying child.

‘Sapnoon ki Sham’ is a romantic story written in the style of Krishan Chander in which an uneducated woman Saaji falls in love with a village teacher who saves her life. She is later married to another person Salaama. Saaji is drowned in the rivulet flowing by while trying to build a bund on its banks to provide help to her husband. The village teacher offers a wreathe of his tears to the deceased while sitting on the bank of the rivulet. ‘Mere Bache Ki Saalgirah’ (The Birthday of my Son) is a story of dreams and apprehensions with romantic narrative in Krishan Chander style. The story touches the personal life of the progressive writer who is congratulated by his friends prophesying that ‘Mao’ had taken birth in his house in the shape of his child. Needless to say that the writer must have felt proud dreaming his child to be a Mao in the making at a time when Socialism was regarded as the ultimate goal of a civilized society. ‘Amar Jyoti’ (The Eternal Flame) is another story influenced by Socialism where a Russian lady honours a dead body by digging a grave for him under the cloud of bullets and canons. Later on she lights a flame on his grave. ‘Lamhon Ki Rakh’ (The Embers of Time) is a nostalgic recollection of the narrator’s past love affair with Almas.‘Teesein Dard Ki’ (Writhes of pain) is a story of an apprehensive husband who always doubts his wife for her affair during the premarital days. On the contrary, the wife is magnanimous to look after her husband during his sickness unmindful of the treatment meted out to her by him earlier.‘Khwaboon Ke Dareeche’ ( A Peep into the Dreams) is a story based on sadism and Voyeurism and has a clear stamp of Mantovian style on it.

As per Abdul Gani Sheikh, “Brij Premi nurtured his writings with his blood and never bothered about the returns from such writings”. Moti Lal Saqi is of the opinion that “Premi’s stories describe men in bone and flesh. They transgress the romanticism of middle class and venture into the areas of spiritualism and realism together. On the other hand, Prof. Manzoor Azmi believes that “ He(Premi) creates stories by describing a chain of events but does not believe in unnecessary conflicts between the events and characters in order to give it a melodramatic effect.”

One thing must be admitted here that Dr.Brij Premi picked up his pen at a time when the world of Urdu fiction was dominated by stalwarts like Krishen Chander, Bedi, Manto, Ashq, Ismat Chugtai and Qurratulain Hyder. The centre of activity had shifted to Bombay after the exit of Prem Chand and ‘futwas’ were being issued by writers’ organisations who would not entertain any new comers. Under such circumstances, Dr. Brij Premi had a herculean task to get himself recognized while sitting in a remote corner of India. Further the local problems focussed by him were not considered as mainstream problems of India and therefore overlooked completely. Worse still, his state was the first state announcing land reforms bestowing ‘land to tillers’ which left no ammunition with the progressive writers of the State. Though the political instability witnessed by the state could have provided raw material to Dr. Brij Premi yet he could neither afford to take sides with such elements who were responsible for creating such instability nor could he afford to subscribe to their subversive politics. It would also mean that he had to stake his job for a cause to which he did not subscribe. But then Dr.Premi sublimated his inner desire by turning towards research work and exploring the maniacal world of Manto.

Coming back to Premi’s research on Manto, Premi had to understand Manto’s mind in three phases ; first, the socialist Manto, second,the Freudian Manto, and third, the real Manto. Brij Premi had already been groomed in socialism and had studied Russian writers like Gorky, Dostoevesky and Chekhov. He had also familiarized himself with the writings of the french writer Maupassant who left an indelible impression on the mind of Manto. Premi had to learn the basics of psychology and other behavioral sciences to understand the bulk of Manto’s stories like ‘Thanda Gosht’ and ‘Hatak’. Last of all, Brij Premi had to internalize the pain and agony of migration caused as a result of the division of the country and understand stories such as ‘Khol Do’ and ‘Mozelle’. Nevertheless, Dr. Premi has lived upto the expectations of the Urdu fraternity by documenting the life and works of Manto with deftness and dexterity.

As I said earlier, we lost Dr. Brij Premi at a time when he was in the prime of his life. The best was yet to come from him. Alas, nightmarish turmoil in the valley and consequent migration to inhospitable plains took its toll and snatched us of an inquisitive soul. May God bestow peace up on the departed soul.

*Sh. Deepak Budki is a noted Urdu short story writer and is presently working as Chief Postmaster General, Jammu and Kashmir Circle. Born on February 15, 1950, the writer did his MSc. B.Ed. from Kashmir University and later graduated from National Defence College. He is also an associate of Insurance Institute of India. More than sixty short stories have been written by him till date which have been published in India, Pakistan and other European countries. Reputed Urdu magazine, "Shair" issued a special number (Gosha) on him in September 2005. Two collections of short stories viz '"Adhoore Chehre" (Urdu and Hindi Editions) and "Chinar Ke Panje" (Urdu edition) are to his credit till date. Another collection of short stories, "Ghonsla”, and a collection of essays on criticism entitled "Asri Tehreerein" are in the pipeline.

Brij Premi’s Book Pirated

By Prof. Manazir Ashique Harganvi

Jagdish Chander Vidhavan's book I happened to have in 1991 but an occasion to read it was delayed as the book had got mixed up somewhere in my papers. Prior to it, I had come across many comments of admiration on the author's book 'Manto Nama'.

In "Tarteeb" on Page 03, I could at once call up that this material was there in another book. After going through the book restlessness gripped me and I was forced to get many books (lying in disarray) on Manto as under my guidance a student had been awarded Ph.D on "Stories of Manto".Similarities between Mantonama and Dr Premi's book 'life and achievements of Manto' were seen. Dr Brij Premi had already been awarded Ph.D in 1977 by Kashmir University. Major portions of Jagdish Chander Vidhavan's book are from Dr. Premi's book on Manto. Even the text at many places has been pirated word to word, and somewhere through certain clever permutations and combinations, Sh. Jagdish Chander Vidhavan has tried to make it look like the material as his own, though he has not succeeded by crediting the stolen contents into his book, besides making it look like his personal achievement by copying in a clever manner comments of Krishan Chander and Abu Syeed Qureshi. The rest of the author's contents have been taken from 'Manto Number' from Lahore.

"Dr. Brij Premi, a Srinagar born person got this nourishment in literary activity from Prem Nath Pardesi. Basically Brij Premi was a short story writer, who later shifted to new domain to earn Ph.D from Kashmir University where he was posted as Lecturer in Urdu Deptt. Dr. Brij Premi passed away on 20 April 1990 and by then seven or eight books of Premi were published. Some excerpts and comments:

"The book Manto-Hayat Aur Karnamey was highly liked by me".

Ali Sardar Jafri (Bombay)

"Really, you have tried very hard in collecting and updating events and circumstances and presented very admirably through a wonderful style.”

Prof. Masood Hussain Khan (Aligarh)

Dr. Premi is one among those who work very silently to bring forth genuine documents. He is one among those Indians, who has devoted himself singularly on Manto. This book on Manto's personality and act is indeed of the standard of a basic reference book.

Prof. Gopi Chand Narang (Delhi University)

In my opinion, at least in India, a book like this on Manto has not been published. He has really prepared an encyclopedia on Manto. I feel, rather confidently speaking, that no serious student working on Manto can ignore this book.

Prof. Jagan Nath Azad (Jammu University)

A book of this nature, a composite book on Manto has not been written so far in Urdu. We will see more work done on Manto, but this book shall have the status of a basic reference book.

Prof. Qamar Rais

Brij Premi after departing from and saying good bye to old concepts has brought before us some important facts in Manto's stormy life. With analysis of historical and fundamental criticism, Brij Premi has presented a bias free account of presentation of facts.

Prof. Hamidi Kashmir

On such a beautiful book like this, I can afford to forget at least my half a dozen novels.

Kashmiri Lal Zakir

Jagdish Chander Vidhawan says:-

Research confirms that Mantoos in the last 18th century or in beginnings of 19th century migrated to Punjab (Page-01).

The text of Brij Premi's book seems to have been pirated with a slight change here and there, transported into Mantonama. Excerpts Khoja Jalal-ud-Din who settled in Amritsar was Manto's grandfather whose youngest son Moulvi Gulam Hassan was married twice and had in all twelve children - four sons and eight daughters and Manto was second wife's son. Manto had three step-brothers who were senior to Manto (Manto Nama Page 23). Brij Premi writes Manto was a Kashmiri Pandit like Jawahar Lal Nehru and Iqbal (Page 24) In the series 'Architects of literature' in Page 18 Krishan Chander's reference is Manto like Jawahar Lal and Iqbal was in fact Kashmiri Pandit. Citing Krishan Chander's sentence Brij Prem in his book on Page 18 has made this comment. Now Vidawan says-

In Urdu language Manto is referred to as Mintoo or Manto-(Mantonama 26-27. Following extract in Manto Nama is exactly like one in Brij Premi's Book of life and Achivements of Saadat Hassan Manto.

Manto's house was in Kocha (street) Vakilan in Amritsar and where one could see the house of Hafiz Ullah and outside it there was a well and then a little onwards one saw the house of Abdul Hamed DSP. There was a 'haveli' to the north of which there was Manto's house whose door was on the South and on the right side, there was the way leading to Manto's house. This room was known as Daral Mahar (Manto Nama-Page 31)

This is the text of Abu Syeed Qureshi and Brij Premi uses it in his book on page 35. Near the door.,.... was a writing table and on the right side a small almirah and books that could not be kept in the almirah were on the table along the wall. Manto received his education in Middle and High School and had....(Manto Nama Page 32) Page 32 the full page text. In childhood, once Manto...(Page 23) Refer to Premi’s book Page 34) Manto took up editorship of weekly “Musavir” and accepted a job there in the office of this weekly and lived, nearby on the rent of Rs 9.00 a month-the room was in a very bad condition-he was just a Matriculate and that too with a third grade in the examination--

(Mantonama Page 107)

Refer to Page 107....the text is exactly similar to Page 59...

Excerpts - Manto was asked his opinion about marriage and Manto had assented---one Malik Hassan was the uncle of Manto's would be wife and was a print assistant in the police department---Manto could not really make up with the meagre salary and was used to a beer bottle--the girl's uncle was in parliament, besides being a social worker!!! Safia's father was killed some where in a scuffle or some dispute--and Safia was brought up by her uncle----unfortunately the financial position of Imperial film company was having a bad patch and the conditions grew worse day by day. Even the allowance in place of pay could not be given and the company's proprietor requested for some assistance---All this has been pirated from Brij Premi's book" Life and Achievements of Sadat Hassan Manto".

Excerpts----In all about four to five hundred rupees were spent----Sometimes Safia would appear---and he writes about Safia to his friend Ahmad Nadim Qasmi as---It is not yet a what one calls a perfect marriage---I have been only engaged. My wife is connected to some Kashmiri dynasty. Her father is dead and my father too is dead, she puts glasses as I put...she was born on 11th May the day I too was. Her mother wears glasses as my mother uses---The first letter of her name is also common like so many things to us---Manto shifted to a room on rupees thirty as the rent and pay was rupees forty from "Musavir", just to manage life on Rs 5 a month. Manto kept up the room in the wake of Safia coming to live with him---with him---producer Nana Bai Desai gave him a thousand rupees and eight hundred for his (Desials) Apni Nagar" (Manto Nama Page 110-111) all this has been pirated from Page No: 61 of Premi's book" Life and Achievements of Sadat Hassan Manto.

Excerpts - Manto was employed in All India Radio---and began receiving letters from Nazir Ludhanavi, the proprietor of 'Musavir' to come back toBombay---Manto gave up the job---Shoukat Hussan was some what stubborn and (Manto Nama Page 141) This is a complete piracy frmo Page No: 76 and 77 of Premi's book Life and Achievements of Sadat Hassan Manto”.

Excerpts - Filmstan took up making a propaganda film. Short story writer of Filmstan, Gyan Mukerjee had written a film story but it was rejected and the work was asigned to Manto...who worked quitely, with dedication and changed the fundamental texture of the story. The script was accepted and it was put on the screen.

(Manto Nama Page 165)

The above text, quite word by word" completely resembles the contents on Page 82 from Manto-Life and achievements by Dr Brij Premi--I reached Page 165 from Manto Nama and now I didn't dare go ahead readers can well guess how Jagdish Chander Vidavan has prepared his book

Quarterly Tarkash Kolkata

Shumara No: 04

July 2003

Translated by Sh. M.N. Kak

*(The author is Professor of Urdu at Bhagalpur University).

Brij Premi’s works - A Review

By Prof. Mehmood Hasmi (Birmingham)

Prof. Mehmood Hashmi was born in Ddyal (Mirpur). He has been acclaimed as a great teacher of merit and a scholastic profundity. He worked in different colleges of J&K State and left for Pakistan in 1947. He was associated with broadcasting units at different places in Pakistan.

"Kashmir Udas Hai" is his famous book with some autobiographical elements in it. In addition to it, he has written many short stories and essays regarding different aspects of Urdu literature. He continues to be remembered for his useful contributions to Urdu literature on whose horizon he has left his own imprint. --The Editor

I liked "Manto Katha" really much as one of the books of Dr. Brij Premi. This book will continue to retain its importance and relevance and Premi has really worked hard at it . The letters of Safia Manto are very interesting.

In "Kashmir Key Maz-ameen", the write-up on Pt. Govind Kaul left a profound impact on me. Who knows how many persons of Govind Kaul’s calibre are there from Kashmir and whom we had no occasion to know in view of certain circumstances or non-availability of some reputed persons who could excavate some thing more of this treasure.

In Brij Premi's book "Jalve-e-Sadrang" letters of Sir Aurel Stein to Ram Chand Bali, such impressions were the result. In Kashmir Key Mazameen,the sketch Hamidi Kashmir has been written so artistically and personality of Hamidi Kashmiri comes alive to the reader. After going through this book, the readers will, I am sure, feel prompted to read the write-up again and those who know little about this luminary will be drawn towards knowing more about him. In this write-up, one feels that justice has been done to the standards of writing sketches and the impact is totally positive.

One can’t know why this write-up has been captioned as "Friend, Philosopher and Guide”. I'd say that it could be better captioned as "Dost, Phalsaphi andRehmuna meaning friend, philosopher and guide.

The write-up on Prem Nath Pardesi pleased and impressed me. Those good old days brought back those memories. I met Pardesi in 1945 and we kept company upto 20th of Nov 1947, a period of real intimacy.

In March, 1945 I had been to Srinagar, Pardesi's stories appeared in newspapers of the state and Maulana Tajwar Najeeb Abadi’s (Lahore) magazine Shahkar’. While at Sgr, Pardesi had already left an impact on me by his attachment to story writing and the taste for reading. He too wrote stories and critical essays, which appeared in Adbi Duniya Lahore, Saqi, Delhi, Kitab (Lahore). Perhaps during those days, one write-up had appeared in Shahkaar and its title was "Jamaliyati hes" of Mehdi Afadi.

In Kashmir Key Mazameen, the write-up on Prem Nath Dhar was nice. Dhar came to London in 1978 to 1989 and also came to Birmingham with Mahinder Nath Kaul, BBC TV producer. He had left for me (two) collections of his stories. It is my ill luck that those collections did not reach me and was thus deprived of going through them. The impact of his some stories continues to be on my mind. This I say quite frankly and freely that Dr. Brij Premi has quite sufficiently proved his artistic worth. He has not only done justice to Prem Nath Dhar but also proved his merits as a critic. His write-up on Prem Nath Dhar and 'A story writer-Prem Nath Dhar- are a matter of pride.

In Jalva-e-Sadrang, the essay "Research and Criticism in Urdu in Jammu and Kashmir, is a knowledgeable piece of writing. The title gives an impression that the writer wanted to comment only on those critics who worked within the geographical boundaries of state.”

*(Translated from Urdu by Sh. MN Kak)

Brij Premi's Research on Manto

By Prof. Mohd. Hassan

*The author headed the Department of Urdu JNU and edited ASRI-ADAB, well-known literary journal.

Brij Premi has written a research oriented book captioned "Life and Works of Saadat Hassan Mantoo," which has an edge over all the books and articles written on Mantoo so far.

Brij Premi has provided interesting information, after putting in hard labour and describing in minute detail Manto's family, forefathers and his personality which people in general have no idea of. This book is so full of life that it deserves to be published and included in the monthly 'Asri Adab' again. Brij Premi has effectively analysed Manto's dramas, sketches, short stories and letters etc. He has tried to present in depth and proper context-Manto's thought and art. It is evident that the whole research-oriented work is praiseworthy and it ignores Manto's negative aspects of his bitterness of thought and art. The fact is that Manto steers clear of the unpleasant contradictions of his age and his group. That is the reason why he was popular and among the loved ones and continues to be so, and that again is the reason of his being targeted by critics. Till date this work of Brij Premi is the last word on Mantoo, and for every student of the art of short story writing, this book is worth reading.

*(Translated from Urdu By Prof. M.L. Raina )

Brij Premi — Some Reminiscences

By Dr. M.K. Teng

Brij Premi was the product of the Indian renaissance and the philosophy of rebellion which characterised the time in which he lived the formative years of his life. The community of Hindus in Kashmir was among the first of the Hindu communities in India, which sought its identity in the Indian renaissance and identified itself with the reemergence of the Indian nation and a new social and intellectual commitment to the Sanskrit roots of the Indian civilisation. The Muslims in Jammu and Kashmir like the Muslims in India, rejected the Indian renaissance, because they did not accept the continuity of the Indian history and the civilisational boundaries of unity of the Indian nation. The conflict of ideology was deeper and sharper inKashmir than it was in the rest of India. Kashmir was a Muslim majority princely State of the British empire in India ruled by a Hindu Rajput prince of the Duggar people of Jammu. Brij Premi belonged to the intellectual tradition which bore the influence of this conflict.

Brij Premi was the product of the Indian renaissance and the philosophy of rebellion which characterised the time in which he lived the formative years of his life. The community of Hindus in Kashmir was among the first of the Hindu communities in India, which sought its identity in the Indian renaissance and identified itself with the reemergence of the Indian nation and a new social and intellectual commitment to the Sanskrit roots of the Indian civilisation. The Muslims in Jammu and Kashmir like the Muslims in India, rejected the Indian renaissance, because they did not accept the continuity of the Indian history and the civilisational boundaries of unity of the Indian nation. The conflict of ideology was deeper and sharper inKashmir than it was in the rest of India. Kashmir was a Muslim majority princely State of the British empire in India ruled by a Hindu Rajput prince of the Duggar people of Jammu. Brij Premi belonged to the intellectual tradition which bore the influence of this conflict.

I came in close contact with Brij Premi in 1963, when I returned to Kashmirafter the completion of long years of research at the University of Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh, the heart of Hindu India in 1963. Those were the years when the Indian academics were inspired by a new vision of freedom which was total and universal, and which transcended the half-way freedom the liberalist reformism of the Indian national movement espoused. In Kashmir, I found, though not to my surprise, that the new vision of total freedom had already become an inseparable part of the intellectual and academic discourse of the community of Hindus and the Hindu intellectual class had already joined the search for models of change, almost on the same lines, on which the search for models of change was under way in the other parts of India. Brij Premi was a part of the search of the Hindu intellectual class ofKashmir for models of social change?which encompassed economic, social and political change, and which underlined the recognition of total and universal freedom as its main goal. Brij Premi's literary work and research reflect the struggle of the mind of the Hindu community in Kashmir to grow out of its narrow local focus of freedom and identity, its aspirations with the wider aspirations of the nation of India growing out of slavery and foreign dominance.

Brij Premi symbolised the quest the Indian nation was involved in. His commitment to provide an insight into Sadat Hassan Manto was to unravel the temper of the rebellion Manto's work represented. Manto repudiated the identity of a narrowly dated sectarian identity of India. Rightly, perhaps, Brij Premi made the revelation that Sadat Hassan was of Kashmiri origin and a descendent of a Kashmiri Pandit family which had converted to Islam. He brought the rebellion which lay suppressed in the generations of Manto's past, out of its confines to coordinate Manto's outlook with the quest for a national identity which symbolised total and universal freedom. Sadat Hasan’s work was a severe reaction against the communalisation of the Indian society and the destruction it brought in its wake, which eventually unfolded in the tragedy of the partition. Brij Premi's research on Manto was primarily aimed to correlate his own search for a national identity which Sadat Hassan had sought to establish.

Brij Premi's short stories, his interest in the history of Kashmir, his work of a literary critic of Urdu literature, in which he excelled, reflected the same quest. Brij Premi, was throughout his life, a Kashmiri Pandit, whose dream of freedom had been shattered by the enforcement of the religious precedence of the Muslims in Jammu and Kashmir and who sought to give expression to his intolerance to oppression.

Brij Premi was a traditional Marxist who did not metamorphose into a communist and a party cadre. He talked to me, though hesitantly, about the broad contours of the Marxist approach to social change. He did not doubt the validity of the principal concepts of Marxism: the exploitative character of all class-society; the historical necessity of progress of all society from more exploitative forms to less exploitative forms; the role of the exploited and oppressed peoples in the revolutionary moments for change and the functional attributes of the state and its instrumentalities of authority to sustain exploitative forms of class society. Often our discussion, which he always kept at an informal level, centered upon the principal focus of the character of the Indian state. Was the Indian state different from the instrumentality of power that Marx considered the state to be?

The reformist foundations of the Indian state, which during the early decades of freedom were given a more radical content by the leadership of the Indian National Congress, had imparted a new definition to state function in a class society. The emphasis on change in the Indian society aimed at the attraction of class roles Nehru's concept of "socialistic pattern of society" and "full socialism" envisaged and the techniques of social engineering incorporated in the Directives of State Policy—a commitment of the Congress Left, was an attempt to give a new content to state function. Brij Premi, like other Marxists was unsure of Nehru's doctrine of state function in a class-society, yet adhered to it tenaciously like his comrades did. I harboured no illusions about Nehru's claims to convert the Indian state into an instrumentality of reform. Like the other Marxists of the Hindu community of Kashmir, including those who were members of the Communist party and their comrades, Brij Premi did not agree with me, though he did not give expression to his disagreement.

The cadres of the Communist Party of India and the Marxists, followed their own versions of the role of the state in a class-society. Perhaps, Nehru's outlook provided the cadres of the Communist Party and the Marxists, adequate ground to use the instrumentality of the state to radicalise the process of reform in India and adjust the foreign policy of India to the post-war world, governed by a hitherto unknown phenomenon of bipolar contest of power of the Cold War.

The movement for decolonisation, which dominated Nehru's outlook and the anti-imperialist role of the socialist world, converged, at the ideological level, to an identity of national interest of the socialist powers and the colonial peoples of the world, which had emerged from colonial rule. India was the largest, the most powerful and prestigious of the colonial peoples that came to face the internationalisation of the class conflict which followed the onset of the bipolar power relations in the post war world. The Marxists and the cadres of the Communist Party in Kashmir were conscious of this conflict.Jammu and Kashmir was caught up in the Cold War. The northern frontiers of the State, with a part of it under the occupation of Pakistan rimmed the "soft belly" of the southern frontier of the Soviet Union. The progressive writers ofKashmir, Dina Nath Nadim, Pushkar Nath, Som Nath Zutshi, Bansi Nirdosh and Brij Premi, were all involved in this conflict. Bansi Nirdosh and Som Nath Zutshi, who represented the two extremes of the revolt against exploitative society and identified themselves with the down trodden, recognised the sociological necessity of supporting Nehru's reformism, perhaps, out of their intellectual commitment to social change and their strategic role in the conflict over Kashmir. During Brij Premi's time the intellectual culture ofKashmir was conditioned by the stake, the Hindus of Kashmir had in theKashmir conflict.

The context of this conflict changed in 1990, when the bipolar balance of power came to its end and the Muslims pushed the Hindus out of Kashmir. None of the progressive Hindu writers survived to assess the aftermath. Brij Premi died in April 1990, in the midst of the of disaster the Hindu Community of Kashmir faced. I was in Delhi, living the life of a fugitive.

The Hindus of Kashmir, who formed the main strength of the Marxist flanks and the Communist Party cadres, as noted above, were the product of the Indian renaissance. In contrast to the Marxists and the communists in the rest of the country, the Hindus of Kashmir did not break away from their roots. Most of them did not abandon their commitment to the unity of the Indian nation, its civilisational boundaries and the continuity of the Indiahistory. Brij Premi was no exception. His interest in the ancient symbols of the Hindu civilisation, his keen interest in research in the history of Hindu Kashmir and his rather inexplicable commitment to the Hindu cultural forms, including Hindu ritual structures, is a testimony to his commitment. He found no conflict between the cultural sub-structures of a society and the Marxist concept for change. In fact, he told his son, Premi Romani, without any inhibitions, that there was no conflict between religion and Marxist concept of revolutionary change. In this respect, he was not different from Dina Nath Nadim or Bansi Nirdosh, the two Kashmiri Pandits, who built the tradition of the Indian renaissance into an edifice of social ideology. Perhaps the commitment of the Hindu Marxists in Kashmir to the Indian renaissance formed the basis of their rebellion against all forms of exploitation, including class-exploitation. That is why, secularism, a basic tenet of the Indian renaissance, became an article of faith with them. They were not apologetic about their beliefs and unlike their Muslim comrades, did not seek to legitimise their commitment to Marxism and communism in the theological precedent of Islam and the history of the Muslim Ummah.

Brij Premi carried this struggle, deeper in his consciousness. He was a victim of severe oppression to which the Hindu community was subjected inKashmir. He was denied his due, inspite of his work and research in Urdu language, which the powers that ruled Kashmir those days had insisted upon to declare as the official language of the State. In the long last, Brij Premi was appointed a lecturer in the Department of Urdu in the University of Kashmir in 1977. For Brij Premi, his new assignment was a dream come true. In the University he was cast into a new context, intellectually more purposeful and creative, which provided a wider opportunity for his research and writing.

In the University, he widened the scope of his research. But he was worn down by the isolation to which the Hindus were exposed in the Jammu and Kashmir State. He could not earn any reprieve from the oppression the Hindu community in Kashmir laboured under due to the communalisation of the Muslim society in Kashmir. He met me often, in the department of Political Science in the University of Kashmir. He was not unaware of my unconventional views on the social and political conditions prevailing inKashmir. He complained of the sense of deprivation that had overtaken him and the difficulties he faced in continuing his literary work. The oppression, he faced, goaded him to work more closely on his research projects in history and culture because his presentation of the findings of his investigations in Urdu language, tantamounted to the expression of protest against the oppression, the Hindus faced. Inside him, his feelings about the deep spiritual significance of the Hindu religious belief-system, gradually stirred his conscience. The devotion with which he performed the Pooja at the Shrine of Khir Bhawani at Tula Mula in Kashmir, described by the famed Urdu scholar and novelist Kashmiri Lal Zakir, in his scholarly essay on Brij Premi gives a peep into his mind. Brij Premi confided in me that he was unable to accept that the march of history was determined by logic.That assured him the freedom and perhaps, the perspective of scholarship to recognise the intrinsic quality of the Hindu civilisation of India and the Sanskrit content of the history of Kashmir.

*(The author headed the Department of Political Science, University of Kashmir and has authored many books on Kashmir Politics. His seminal work-Article 370 has received international acclaim).

Premi-An Angel Not A Friend

By Moti Lal Saqi

When I heard the bad news about Dr. Brij Premi's death, I was shocked. He died unsung and unwept. No bells tolled for him because all those who knew and loved him were scattered and are still in disarray. Dr Premi's news of departure came as a bolt from the blue to all his friends. He never deserved such a treatment at the hands of nature, because he loved life.

Dr. Premi died a martyr - a martyr due to exodus of Kashmiri Pandits from the Valley. He was in deep love with his land and people but was made to say good to it. He suffered in exile not for want of money but simply for breathing space. In his heart he was agonised and succumbed to this agony. This fact shall go down in the annals of times to come that exodus of Kashmiri Pandits from Valley deprived them not only of valuables and belongings but also snatched away some brilliant souls from amongst them like Dr. Brij Premi. Had he not been compelled to leave his home and hearth he would have lived for many years more and could benefit us with his ripe experience and overflowing pen. What a tragedy, our official and non-official media remained tight-lipped about the untimely death of Dr. Premi so much so that even a condolence was not offered. This is nothing but the turn of events which speaks for itself. We had heard a lot about the fraternity of pen pushers but all this proved a false dream at least in the case of my angel friend, Dr. Premi who sacrificed his life at the altar of exodus.

Treatment meted out to this noble soul is the alarm of the events that have changed in course of our thinking and approach. All through his short span of life he showered flowers in the way of his friends, colleagues and writers but in turn he was forgotten as if he never existed. Time is the great judge. On the touch stone of time best and pure will show its worth and Dr. Premi will be given his due place in the cultural and literary history of Kashmir. He had carved out a niche for himself in the mansion of our cultural movement and there is none to deprive him of his place come what may? Because sands are sure to settle, glitter shall vanish and base is sure to be rejected.

To me Dr. Premi's death is not simply the death of a friend. It is the loss of a man who was close to my heart. It is the departure of a benevolent angel who was a source of solace and strength for me. For the last thirty five years our friendship stood the test of time and weathered all the storms which came our way..

I know it is not a loss to me alone, there are many people who will remember him for a long time. My personal loss is something greater, something that cannot be made up. His departure has crippled me. I feel my right arm has been cut and sooner or later I have to depart in my crippled state.

Health failed Dr. Premi for the last six or seven years. But his ill health never made him to shun his love and affection for me. He would off and on come from University campus for a chat or to discuss any problem relating to our personal or cultural matters. Though he was not physically fit even then he was full of life.

He was determined to accomplish something more, something novel, which could add to the knowledge of Kashmiriology. It was his earnest desire to complete history of Kashmiri literature in Urdu. He had done some preliminary work in this regard also but merciless jaws of death deprived him the opportunity to accomplish the job.

In his literary pursuits Premi was an infidel. In fifties Mantoo was a symbol of reactionary forces to progressive writers, who were in full command of the situation at that time. Premi on the other hand was all praise for him. He loved Mantoo’s diction, treatment and style of story telling. It was this infidelity which led him to select Mantoo and his writings, as the subject for his Ph.D thesis. His love for this great writer knew no bounds. After the completion and publication of his Ph.D thesis which won him a prize also, Premi wrote a series of articles which appeared in leading Urdu journals and periodicals. He was, of course one of the few scholars who have proved their mettle in the realm of 'Nutoiat'. What Premi thought and believed in fifties came true after seventies when Mantoo was declared undisupted master of short story in the sub-continent.

The sweet memories of the past are the only treasure now left with me. People of my hue and colour are departing one after another. How painful it is that I am left behind to lament and mourn the death of those who sprinkled honey dew on burning soul as and when it was needed. It is not possible at this juncture to recount all that which was shared and what transpired between us. It is the subject that I will tackle at proper time separately. The wound is fresh and pangs pinching. In this atmosphere at least allow me to control my tears, which of their own accord come into my eyes when I think or talk about my best friend. Our friendship was not the alliance of mutual bargaining or self interests, it was an amalgam of heart and thinking.

Dr. Premi appeared on the scene as a short story writer and ended his sojourn as a student and a scholar of History, cultural folk lore, personalities of J&K State. It was his research work which brought him honour and recognition. But this does not mean that he was lacking in any way in the art of short story writing. I remember it very well that his short story 'Sapnon Ki Sham' appeared in Biswin Sadi, it was praised by lot of people and the author received at least two hundred letters praising the treatment and art of short story writing.

Dr. Premi was miles away from self glory and hypocrisy. He was all grace and compassion for those who sought his help and sympathy. This short appraisal is nothing but simply the recollection of some of the things I knew about Premi. I only long to meet him again and enjoy his company for ever. I know my dream will not materialize here, but, I am sure, we will meet again where and when that is the question of destiny and time because I firmly believe in the transmigration of the soul.

*Born in 1936 at Badiyar Bala, Srinagar. Poet, Writer, Historian, Researcher, Translator, Editor and Author of many books in Kashmiri & Urdu languages. Sahitya Academy Award Winner. He was honoured with Padmashree for his overall contribution to literature.

Dr. Brij Premi was a Gentle Colossus

By Dr. R.K. Tamiri

Dr. Brij Premi lived for just fifty-five years, yet he left behind a solid legacy in the form of brilliant creative literature, which many would envy. He had his tryst with Urdu literature through short stories. His monumental work on Saadat Hasan Manto, the enfant terrible of Urdu literature earned him fame. It also made Manto better known. Dr Brij Premi's literary biography of Pt. Prem Nath Pardesi, an eminent litterateur of yesteryears, is a pioneering work. It has yet to see the light of the day. Dr. Premi was in deep love withKashmir and took pride in its rich past. This made him explore Kashmir in all its dimensions—Historical, Cultural, Social, Literary etc. His work in this field parallels that of Mohiuddin Fauq, another outstanding historian of Kashmiri origin. Dr Premi had suave temperament and was full of affection for others. He was a gentle colossus.

Dr. Premi's family lived in the ancient locality of Drabiyar, in Habbakadal quarter of Srinagar. He was born on 24th September, 1935, which happened to be the day of Janam Ashtmi. His parents decided to name him Brij Krishan. Sometime independence, the family shifted to Rang Teng, Ali Kadal in a rented accommodation. Dr. Premi had his early education from DAV High School, Srinagar.

Pt. Sham Lal Aima, father of Dr. Premi, was an able teacher and a man of many parts. He was a good short story writer. Such men of literature-Pt. Nand Lal Talib, Pt. Kashyap Bandhu, Pt. PN Bazaz, Pt. Prem Nath Pardesi, etc. would often drop at his house. Dr. Premi grew up in this ambience and imbibed interest in literature. He had his initial grooming under his father. Later, Pt. Prem Nath Pardesi became his mentor.

The death of Pt. Sham Lal Aima at young age of 44 in 1949 came as a major setback to Dr. Premi. He was just 14, but the only eligible member in the family who could succeed his father as the bread earner to take care of two brothers, a sister and mother. Young Premi, who had just enrolled himself as a science student in the college, was recalled back. He was employed in place of his father and served in 'Boy Service' for two years, before being recruited as a regular teacher. He was posted in Modern School, Amirakadal on a monthly salary of Rs 30.