Dr. M. K. Teng

Dr. M.K. Teng got his Ph.D. Degree from the University of Lucknow. Dr. Teng was sometime Lecturer in Sri Pratap Government College, Srinagar. He has written profusely on Government and Politics of India and political Development and Government in Kashmir. He has written several books and Research Articles on Politics of Kashmir.

Articles

Return of Hindus to Kashmir

By Dr. M.K. Teng

November 2011

The ethnic cleansing of the Hindus of Kashmir in 1990, is one of the few episodes, which occurred after the second World War, and in which a whole community of people was subjected to genocide and driven out of its natural habitat. The terrorist violence with which the Muslim Jehad in Kashmir commenced in 1989, was aimed to achieve a number of military objectives which the militant regimes and the Jehadi war groups considered to be essential for the liberation of Jammu and Kashmir from the Indian occupation. The ethnic extermination of the Hindus was one of the primary objectives, the Jehad aimed to achieve. The Hindus of Kashmir formed the Sanskrit component of the social culture of Kashmir and provided the Muslim majority state of Jammu and Kashmir its secular identity. More importantly, the Hindus formed the frontline of the resistance against the separatists movements in the State, which the Muslim separatist forces carried on for decades with the support of Pakistan.

Ever since the commencement of their exile, the Hindus have been waiting for their return to the land of their birth, reiterating from time to time their resolve to return to their homes. The response of the Indian State to their remonstrations was always feeble and continues to be so even now; mainly determined by the inability of the Indian political class to recognise the real import of the terrorist violence and its inaptitude to deal with the Muslim Jehad with any firmness. The Indian political class closed its eyes, like the ostriches do, to the death and devastation, the terrorist violence brought to the Hindus of Kashmir and to the Hindus of the Muslim majority districts of the Jammu province.

The Indian leaders never mustered courage to face the Muslim Jehad, without which the return and rehabilitation of the Hindus could not the achieved. Instead the Indian political class adopted a surreptitious policy of compromise with the Muslim separatist flanks. The Indian political class ascribed the terrorist violence to the alienation of the Muslims in the State which it traced to the inability of the Indian political system to recognise the genuineness of the Muslim struggle for a separate freedom in Jammu and Kashmir. Assuming a position in between the Jehad and the Hindus of the State, the Indian political class sat on judgement on who had done what in Jammu and Kashmir, to fix the responsibility for the Muslim alienation and the consequent upheaval in the State. Expectedly, the Jehad triumphed and the Hindus continued to smoulder in exile.

Genocide of Hindus

The genocide, the Hindus in Kashmir, were subjected to and the exodus forced upon them by the terrorist regimes, right from the moment they began their military operations in the State, was undertaken in accordance with a well laid out plan. The plan envisaged the ethnic extermination of the Hindus in the Kashmir province and the Muslim majority regions of the Jammu province to bring about the de-Sanskritisation of the part of the State situated to the west of the river Chenab and prepare the ground for its separation from the Shivalik plains, situated to the east of the river Chenab. The division of the State in between India and Pakistan had been proposed as a basis for settlement of the dispute over Jammu and Kashmir, by the United Nations mediator on Kashmir Sir Owen Dixon in 1950. When the terrorist regimes, extended their military operations to the Muslim majority districts of the Jammu province, they followed the same “scorched earth”, policy there to bring about the ethnic extermination of the Hindus. In Kashmir as well as the Jammu province the first bullets fired by the militants were received by the Hindus.

The Hindus had always formed the frontline of the peoples’ resistance to all forms of Muslim separatism in the State. The Hindus had fought for the freedom of the State from the British rule and when the freedom came, they had paid the heaviest price to defend it against the invading forces of Pakistan in 1947. Not many people in India know that more than thirty eight thousand of Hindus and Sikhs were killed by the invading armies across the territories of the state they over ran.

The first staggering blow which the Jehad delivered to the Hindus in Kashmir was the assassination of Tika Lal Taploo, a Kashmiri Pandit leader, who was widely respected in his community. A member of the National Executive of the Bharatiya, Janata Party, Taploo was an indefatigable man, who had fought untiringly against the marginalisation of the Hindus in the State. Taploo was given a tearful farewell by thousands of the people of his community, who accompanied his funeral procession. While the funeral procession, carrying Taploo on his last journey, wound its way through the streets of Srinagar, stones were pelted on it.

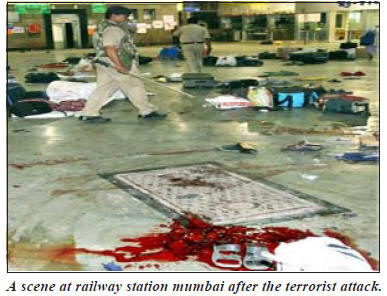

The terrorist violence struck the Hindus in its full fury in January 1990. The death and destruction it brought to the Hindus was widespread. Not much of what happened those days in Kashmir is known in the rest of the country as a concerted campaign of disinformation was carried on to camouflage the ravages the community of the Hindus was subjected to. By the end of the year, the death toll of the Hindus had risen to about eight hundred. The white paper on Kashmir, the Joint Human Rights Committee, Delhi issued in 1996 noted : “A computation of the data of the massacred Hindus on the basis of reports in the local press, news papers published in Srinagar, and the other townships in Kashmir, reveals that the number of the Hindus killed ran into several thousands”. The White Paper notes further “Among the killed were several hundred Hindus who were reported missing. Among the missing were many Hindus whose bodies were never identified and were disposed off by the State Government agencies at their will. Many of the people killed and still to be identified were Hindus.” The chaotic manner in which information about the killings were reported is shown by the following wireless message, transmitting information of the death of two Hindu men, in Srinagar to their kin in Jammu, “To SSP Jammu L.B. No: 13 from Police Control Room Srinagar, 25/6/1990. Please contact Shri Makhan Lal Sumbli H.No: 28 Bhagwati Nagar and inform him about the death of Som Nath S/o Shri Lassa Koul and Chaman Lal S/o Shyam Lal R/o Pattipora Bala, Chattabal, Srinagar, the above dead bodies were lying unidentified at Ali Jan Road. Signature of officer, 1920 ToR, S.P. Police Control Room.”

As the Jehadi war groups and the terrorist regimes settled down to carry on a prolonged war of attrition in Jammu and Kashmir, they changed their tactics. They reduced the frequency of sporadic surprise strikes on specifically identified targets to pre-planned major military strikes on Hindu localities to carry out mass-massacres. The mass massacres were brutal and had s staggering effect on the entire community of the Hindus in the State. The massacres were carried out at different places in the Kashmir province : at Sangrahampora where eight people were killed; at Wandahama in North Kashmir, in January 1998, where twenty three Hindus were killed; at Anantnag in South Kashmir, where twelve Bihari labourers were killed in July 1999; at Chattisinghpora where thirty-six Sikhs were killed in March 2000, at Pahalgam, where thirty-two Hindus, including twenty-nine pilgrims to Amarnath Shrine, were killed in August 2000; and at Nadimarg, where twenty-four Hindus were killed in March 2002.

In the Jammu province, the mass massacres were widespread and the death-toll heavier. Seventeen Hindus were killed in Kishtwar during 13-14 August 1993; sixteen Hindus were killed in Kishtwar in January 1996; Seventeen Hindus were killed in Simber, Doda in May 1996; twenty-nine Hindus were killed in Dakhikot Prankot, Doda in January 1998; Eleven Hindus (defence committee members) were killed in Dessa, Doda in May 1998, twenty nine Hindus were killed in Chapnari Doda, in June 1998; twenty Hindus were killed in separate terrorist attacks in Chinathakuri, and Shrawan, Doda in July 1998; seventeen Hindus were killed in Surankot Poonch in June 1999; fifteen Hindus wee killed in Thatri, Doda, in July 1999; seventeen Hindus were killed in Manjakot Rajouri in March 2001; fifteen Hindus were killed in Cherjimorah, Dodain July 2001’, Sixteen Hindus were killed in Sarothdhar, Doda in August 2001’, Thirty four Hindus were killed in Kaluchak, Jammu in May 2002; twenty-nine Hindus were killed in Rajiv Nagar, Jammu in July 2002; seventeen Hindus were killed in Udhampur in March 2003; twelve Hindus were killed in Surankote, Poonch in June 2004; ten Hindus were killed in Budhal, Rajouri in October 2005; three of a Hindu family were killed in Chaal, Udhampur in April 2006 and thirty Hindus were killed in Thana Kulhand, Doda in April 2006.

Exodus

The Indian State having failed in its rightful function to protect the Hindus in Kashmir from death and destruction, the terrorist flanks brought to them, they were left with no other course except to leave their homes to save their lives. The massacre of Hindus was aimed to eliminate them physically and at the same time fill their hearts with terror to force them to leave Kashmir. The Hindus, unable to believe that they would be abandoned by the Indian state, to face the Jehad as best they could, offered themselves as easy targets for the terrorist flanks and allowed hundreds of their brothern to be killed. But as the holocaust enveloped them, they left their homes and hearths to save their lives and the lives of their children. The White Paper on Kashmir noted: “A deliberately designed two-pronged plan to dislodge the Hindus from Kashmir was surreptitiously put into operation by the various terrorist organisations. Several hit lists were circulated all over the Valley, in towns as well as villages. The hit lists were accompanied by rumours about the Hindus who were found by the militants to have been involved in ‘Mukhbiri’, complicity, with the Government of India. The rumours were deadly, because they made life uncertain”. The White Paper noted further: “In a number of towns and villages, the local people issued threats from the mosques and spread rumours charging the Kashmiri. Hindus of conspiracy and espionage in order to break their resolve to stay behind. Larger number of prominent men among the Kashmiri Hindus, social workers, leaders and intellectuals were listed for death. Most of them escaped from the Valley, secretly to avoid suspicion and interception.”. The attack was open. The White Paper noted : “In the rural areas of the Valley, cadres of the secessionist organisations and their supporters, almost of every shade and commitment, the supporters of the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front in the vanguard, did not hide their hostility towards the Hindus. At many places, even in Srinagar and the other townships, Kashmiri, Hindus were openly charged of espionage for India. The indictment spelt death”.

The exodus of the Hindus picked up pace as the summer set in. By the end of the year 1990, the larger part of the Hindu community of Kashmir had left. The rest followed as the terrorist violence intensified.

While the Hindus began to leave Kashmir the Jehadi flanks unfolded their plans to destroy the Sanskrit heritage of the Kashmir. The homes the Hindus left-behind, were ransacked and after their properties were looted, burnt down. Within four years of the onset of the terrorist violence in Kashmir, 18,000, Hindu houses were burnt down, bombed and demolished. The White Paper on Kashmir noted : “Many of the homes were torched and during the last four years about 18,000 were either burnt down or destroyed. Many of the homes, which were not burnt, were occupied by mercenaries serving the militant organisations. The premises of the business establishment, shops and commercial establishments were also taken over by the Muslim activists who supported the militancy. In the rural areas, agricultural lands, orchards, and the lands attached to the burnt Hindu houses, were nibbled away by Muslim activists supporting various terrorist organisatiosn. The cattle and the livestock left behind by the Hindus, were sold for slaughter”. In due course of time as the militancy continued to ravage the province and the Muslim separatists forces and the Jehadi flanks gained an upper hand, the Hindus were dispossessed of whatever they owned, their land, dilapidated structures of their homes, business establishments and other assets by what came to be called the distress sales.

The depredations the terrorist regimes wrought did not end with the destruction of Hindu localities, homes and properties. They attacked the temples and Hindu places of worship with iconoclast zeal. The Minister of State for the Home Department of the Government of India told the Indian Parliament on 12 March 1993, that thirteen temples were desecrated and demolished in 1989, nine temples were damaged and demolished in 1990, and sixteen temples were damaged and demolished in 1991. The White Paper on Kashmir noted : “The actual number of temples demolished and damaged in Kashmir was much larger and vandalism to which the Hindu shrines were exposed was widespread”. In the aftermath of the demolition of the Babri Majid, the militants and the Muslim mobs joined to attack the Hindu temples and places of worship. On 7 December, 1992, one day after this demolition of the Babri Majsid, two temples, one in Anantnag and one in Srinagar, were burnt down. During the night of 7-8 December, thirteen temples : one each in Kulgam and Sopore; two in Tangamarg; three in Srinagar and one each in the Anantnag, Uttrasu, Shadipur in Sumbal, Pahalgam and Verinag, were damaged and burnt down. On 9 December, two temples were damaged and burnt down at Trehgam and Pattan. The demolition of the Hindu temples continued after 9 December, for many more days taking the number of the temples, desecrated damaged, demolished and burnt down to thirty-nine. The White Paper on Kashmir noted : “After the demolition of the Babri Masjid, the wanton destruction of the temples in Kashmir was reported by the press, though reservedly. Angry demonstrations and protest against the descration and systematic demolitions were held by the Hindu refugees in Jammu and the other parts of the country”. The protest evoked no response from the State Government or the Government of India.

The ancient ruins of the Hindu temples, most of them protected monuments of the Archeological Department of the State and the Archeological Department of the Government of India, were also subject to attack. The archeological remains of the ancient Hindu temples stood as an elequent testimony of the Hindu heritage of Kashmir. The temple ruins were sacred to the Hindus, who visited them as a part of their tradition. At many place the ruins were dug up, in order to obliterate their last traces.

The Hindu religious places where Hindu cultural and social institutions and organisations were located were subjected to bomb attacks or burnt down. The Hindu educational institutions were burnt down or taken over. The entire organisation of Hindu schools and colleges run by the Hindu educational societies including the institutions run by Hindu Educational Society, Dayanand Ayurvedic organisation and the Vishwa Bharti Trust were seized and taken over by the Muslim organisation supported by the militant flanks.

Reversal of Genocide

Genocide of the Hindus in Kashmir and their exile for decades, has changed the geographical alignments of their community in the province of Kashmir and destroyed their social and economic base. The terrorist violence has obliterated the Hindu religious heritage of Kashmir and almost efaced the Hindu cultural identity. The return of Hindus to Kashmir can assume meaning and effect only in case the genocide is reversed.

The issues which form the core of their return are : (a) the reconstruction of their economic and social base; restoration to them of their homes, land, properties, business establishment and institutions and assets; (b) recognition of their right to freedom of which the content is determined by the imperatives of secularism rather than the Muslim majority identity of the State; and (c) acceptance of their territorial claims in Kashmir in case of any settlement with the Muslims of Kashmir to reorganise the the state into a separate Muslim sphere of power on the territories of India, inside India or outside India.

No one can expect the Hindus to return to Kashmir without their sources of livelihood being restored to them and a level of economic security ensured for them. They have lived as refugees in Jammu and the other part of India for two decades. They cannot be sent to live in Kashmir as refugees in improvised camps at the charity of the world.

The Indian political class should realise that the Hindus have lived, almost all over the six decades of the Indian freedom, within the space provided for them by the precarious balance between the commitment of the Indian people to secularism and the Muslim majority identity of the State. The Indian leadership should realise that the Jehad has severely impaired this balance and obliterated the space for the Hindus to live in Kashmir. It must be noted that any attempt to force the Hindus to accept to live in the space earmarked for them by the Muslim identity of the State will prove distasterous for them.

For those who rule India, the return of the Hindus may be a mere change of face, the Muslim identity of the state is given. But for the Hindus of Kashmir, it is a momentous, decision which will determine the future of their generations. The Government of India must apprise the Hindus of Kashmir about the baseline of its approach to any future settlement, it is committed to reach with Pakistan on the one hand and Muslims of the State, on the other. The Hindus do not want their return to be used as a first step towards turning Jammu and Kashmir into a separate Muslim sphere of power, on the territories of India but independent of its constitutional organisation.

The return of the Hindus to Kashmir is a historical necessity, not only for the Unity of Jammu and Kashmir, but for the unity of India. Any cosmetic effort to bring about the return of the Hindus to Kashmir, aimed to provide a secular face to what the Indian political class has brought about in Jammu and Kashmir, during the last two decades, will spell disaster for the Hindus and perhaps lead to developments which do not augur well for the whole country.

After the Hindus were driven out of Kashmir in 1990, their return to their homes was never under the consideration of the people who have ruled India. Indian leaders never had the courage to deny Pakistan and the Muslim separatist forces the claim they lay to Jammu and Kashmir, on the basis of the Muslim majority composition of its population. Nor did they possess the resolution to fight against the religious war that Pakistan and the Jihadi war-groups operating inside as well as outside the State waged to unite it with Pakistan.

The Indian political class assumed complete silence over the death and devastation the Jihad wrought in Kashmir. In fact, it spared no efforts to camouflage the genocide of the Hindus and their ethnic cleansing in Kashmir and Muslim-majority districts of the Jammu province.

Stray references by Indian leaders on the return of Hindus to their homes and hearths “with honour and dignity” were part of the propaganda to minimise the impact of the displacement of Hindus in the State and contain its effects. Behind the scenes, the Indian political class tried practically to negotiate peace with the Muslim separatist flanks inside the State and their Jihadi mentors outside the State. Negotiations for peace with Jihadi war groups who were later joined by Pakistan, left hardly any space for the return of the Hindus to Kashmir, who had been driven out by the Jihad for having harmed the cause of the freedom of the Muslims of the State.

The Indian Government and the State Government never made their stand clear on the genocide of the Hindus and the exodus forced upon them. They did not make their stand clear on the reversal of the genocide, which formed the precedent condition for the return of the Hindus to their homes. In fact, the Indian Government never made any formal commitment in respect of the return of Hindus to their homes and made no concrete proposals for their rehabilitation.

Disinformation Campaign

The Indian political class launched a widespread dis-information campaign to camouflage the portent of the terrorist violence and conceal the real purpose of the Jihad in Jammu and Kashmir. The White Paper on Kashmir issued by the Joint Human Rights Committee, Delhi, noted: “All over the post-independent era, incessant efforts were always made by the State Government and the Government of India to conceal the ugly face of Muslim communalism in Jammu and Kashmir. Deliberate attempts were always made to provide cover to the growth of the Muslim fundamentalist and secessionist movements in the State, right from the time of its accession to India. The various forms of Muslim communalism and separatism which ravaged life in the State during the last four decades and which imparted to the secessionist movements in the State their ideological content and tactical direction, were camouflaged under the banners of sub-national autonomy, regional identity and even secularism. Largely perceptional aberrations, misplaced notions, and subterfuge characterised the official as well as the non-official responses to the upheavals which rocked the State from time to time. More often, the real issues confronting the State were overlooked by deliberate design and political interest, a policy which in the long run operated to help the secessionist forces to consolidate the ranks and their hold on the people in the State”.

No sooner had the Jihad commenced in Kashmir than a mild goose chase began in search of scapegoats to camouflage the forces involved in the upheaval. “Even after widespread militant violence struck Kashmir in 1989,” the White Paper on Kashmir noted, “and thousands of innocent people were killed in cold blood along with hundreds of Indian security personnel and the whole community of Hindus in Kashmir was driven out of the Valley, the disinformation campaign continued to cloud the real dangers the terrorist violence posed to the nation. Indeed efforts still continue to be made to side track the basic problems of terrorism and secessionism and the role of the militarized Muslim fundamentalist forces in the whole bloody drama enacted in the State and divert the attention of the Indian people to trivial concerns, which have no bearing on the developments there.”

The disinformation campaign succeeded only partially to provide a smokescreen to what the Jihad wrought in Kashmir and the Muslim-majority districts of Jammu province. Yet a part of the truth was revealed by the leaders of the mainstream political parties of the State, the National Conference and the Peoples Democratic Party, when they admitted that the basic cause of Muslim unrest was the political issue which underlined the Kashmir dispute. The rest of the story of the Jihad which has continued in the State unabated for the last two decades is still to be told. A large part of the truth of what the war of attrition wrought in the State is still not told.

Perhaps, at one time, the Jihadi regimes and their over-ground political outfits found it necessary to tell the Indian people frankly that the Muslim struggle in Kashmir was aimed at the liberation of the State from India.

A part of the truth of what happened in Kashmir was actually revealed by the Jihadi regimes themselves and their over-ground separatist outfits like Hurriyat Conference. The Indian political class had ascribed the militant violence to alienation of Muslim youth wrought by Indian misrule which had led to economic deprivation and political oppression of Muslims. The Jihadi regimes told the Indian people and the world that the Muslim Jihad aimed to liberate the State from the occupation army of India, stationed in the State illegally. The Jihadi regimes and Muslim separatist organisations denied that the militant operations and Muslim upsurge accompanying them were in any way related to political distrust, economic deprivation or alienation of Muslims in Jammu and Kashmir. They made it clear in unmistakable terms that the Muslims in Jammu and Kashmir had commenced the Jihad in Kashmir to liberate the J&K State from the “illegal occupation of the Indian army” and unite it with the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

A part of the truth was told by the leaders of mainstream National Conference and Peoples Democratic Party who had ruled the State before the onset of the militant violence as well as after it. Without mincing words, they accepted that Muslim unrest in the State and Muslim struggle were an expression of the peoples’ desire to seek a settlement of the central issue underlying the Kashmir dispute. They gave ample expression to their opinions stating that so long as the Muslim quest for a separate freedom which was not subject to the secular imperatives of the Constitution of India, and so long as a settlement of the Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan and the Muslims of the State was not found, the distrust would not end.

Yet a part of the truth is still concealed. The story of the genocide of the Hindus, their ethnic extermination and how they were used as scapegoats for the failings of the Indian political class in dealing with the Jihad, is yet to be told. This part of the untold truth is closely linked with the return of the Hindus to their homes and hearths. The Indian political class is hiding the truth of what the Jihad has wrought in Kashmir during the last two decades. Indian Governments have never mustered the courage to stand up to the Jihad. The Indian political class is still following its own plans to use the Hindus in Jammu and Kashmir as a buffer in between them and the war of subversion the Jihadi regimes are waging in the State. The double-speak of the Indian political class on the return of Hindus to Kashmir is bound to do them more harm.

The truth is that the security environment in Kashmir province is severely strained and the social culture of the Muslim community has been drastically changed by the Jihad. The Hindus of Kashmir were driven out on the point of the gun because of their resistance to the Muslim separatist movements in the State. Their opposition to the Muslim Jihad assumed nation-wide proportions during the last two decades of their exile. They will hardly find it easy to come to terms with the conditions that prevail in Kashmir, while the religious war continues unabated.

It may not be out of place to mention here that the over-ground political outfits of the Jihadi war groups and militant flanks, including various factions of Hurriyat Conference, have offered to accept the return of Hindus and at the same time expressed hope that after their return they will join their Muslim brethren in their struggle for liberation from India!

Changed Milieu

First, the ethnic cleansing of Hindus has dissolved the pluri-cultural social organization of Kashmir. The demographic alignments which existed in Kashmir before the onset of the Jihad formed the basis of its multi-religious social organization. In the tradition-bound societies of former colonial peoples, demographic alignments have been found to play a major role in determining inter-community relations in their social cultures. The social culture of Kashmir has assumed a dominantly Islamic expression. No wonder that during the last several years, Kashmiri Pandits going on pilgrimage to the shrine of Khir-Bhawani in Tulamulla on the outskirts of Srinagar onZeshta-Ashtami, have been greeted at the gate of the shrine by a crowd of Tablighi Muslim volunteers who distributed Islamic literature among the pilgrims.

Secondly, the fundamentalisation of Muslim society in Kashmir – a process which began for nearly a decade before the onset of terrorist violence in 1990, has led to the regimentation of large sections of Muslim society on the basis of ideological commitment to the Islamisation of the State. Most of the regimented sections of Muslim society are militarily responsive. The regimentation of Muslim society has already led to the fundamentalisation of the entire social culture of Muslim society in Kashmir.

It is difficult to conclude that the Indian leaders are not able to realize the risks in sending back Hindus to Kashmir in a situation of conflict. The truth is that the Indian political class follows a measured policy in regard to J&K, which does not underline the return of Hindu refugees to their homes. The Indian political class seeks to graft the return of Hindu refugees to an overall settlement of the Kashmir dispute with Pakistan and the Muslims of Jammu and Kashmir. Had it been otherwise, the Indian Government would have opened talks with Hindu refugees of Kashmir, before they conceived of a settlement with Pakistan or the Muslims of the State.

Peace Process

A discussion on what constitutes the Kashmir dispute is outside the scope of this paper. Suffice it to say that the Indian political class recognizes Kashmir dispute to be what Pakistan and Muslim separatist flanks in J&K construe it to be. The Indian Government has in principle accepted the Kashmir dispute to be the expression of the claim that Pakistan lays to J&K on the basis of the Muslim-majority composition of its population and the claim made by J&K Muslims to a separate freedom to which the Partition of India entitled them on the basis of the ratio of their population in the State. Negotiations for a settlement of the Kashmir dispute, originally initiated by the Indian Government and which have now assumed the brand name of “political process”, underline a quest for an agreement which India seeks to reach with Pakistan and the Muslims of the State.

The “peace-process” has been conducted at many levels: between the governments of India and Pakistan, back-channel diplomacy, third power mediation and negotiations between the Indian Government and various Muslim separatist and mainstream political organisations and outfits inside the State. Interestingly, Pakistan has made its position clear that it will accept a settlement on Kashmir dispute which is approved by Muslims of the State. The Muslims in Jammu and Kashmir have also made their stand clear that they will agree to a settlement on Kashmir which is acceptable to Pakistan.

The “peace-process” has largely revolved round the claim Pakistan has laid to the Muslim majority regions of the State: the province of Kashmir, the Muslim-majority districts of Jammu province, and the Kargil district of Ladakh region, as a baseline for settlement of the Kashmir dispute. The two countries came close to acceptance of the reorganization of the Muslim-majority regions of the State into a separate sphere of Muslim power placed in between the two countries under some form of protectorate. The Manmohan Singh-Musharraf proposals, on which the two countries are reported to have come to an agreement, underlined the reorganization of the Muslim-majority regions of the State into a separate political structure, which was based upon the territory of India, but placed under the political control of both India and Pakistan.

The “peace-process” is still in progress. But the Indian political class has given no indication of how it will graft the return of Hindu refugees to Kashmir to the commitments given to Pakistan and the Muslims of the State in respect of settlement of the dispute over Jammu and Kashmir.

Road Ahead

The uprooting of Hindus from their homes in Kashmir was one of the major displacements of people in the aftermath of the Second World War, in which a whole community was torn from its roots. The White Paper on Kashmir notes: “Like the other tradition bound, endogamous and native people, the Hindus, with an incredibly long history, extending to pre-historic, proto-Aryan, later Stone Age Culture, formed an independent part of the cultural identity of the State and its personality. Because of their endocrine cultural patterns, local ritual structures, blended with the Vedic religious precept and practice and their pride in Sanskrit civilization, they had a deep sense of attachment and belonging to their land, which they addressed in their worship as the Mother, who had given them birth”. The displacement of Hindus thus snapped their history.

scattered in a state of diaspora, which threatens them with the loss of their identity. Nearly half the people of the community are living at subsistence level in refugee camps in various parts of the country.

Ever since the commencement of their exile, the Hindus of Kashmir have been waiting to return to the land of their birth, reiterating their resolve from time to time to go back to their homes and hearths. The Hindus were driven out of their homes by a religious war which brought them death and attacked their faith. The political class of India is yet to accept that the delegitimisation of the religious war is a precedent condition for the reversal of their genocide.

The Hindus have as sacrosanct a territorial right in Kashmir as their Muslim compatriots. The claim made by Pakistan to Jammu and Kashmir State on the basis of the Muslim-majority composition and the claim made by Muslim separatist flanks inside the State for a separate freedom, do not in any respect prejudice the territorial right that Hindus claim in Kashmir.

Prof MK Teng is Political Adviser, Panun Kashmir, and retired Professor & Head of the Political Science Department, Kashmir University, Srinagar

Kashmir: Greater Autonomy

by Dr. M. K. Teng, C. L. Gadoo

(Joint Human Rights Committee WA-88, Shakarpur, Delhi - 110092)

Terrorism in Jammu and Kashmir has almost broken up the national consensus on major functional attributes of Parliamentary

government in Jammu and Kashmir. There is a deep difference of opinion about the feasibility of a political package on 'greater autonomy' to the State; Hindus and the other minorities, about 46 percent of the population of the State, opposed to any restructurisation of the existing constitutional relations between the Union and the State, and the Muslims uncertain of whether the so-called package of autonomy would be acceptable to militant regimes as a basis for settlement with the Indian Govemment. Perhaps, the Govemment of India believes that it can substitute 'greater autonomy' for the 'right of self-determination', that the Muslim secessionist forces, militarised by Pakistan in 1989-90, have been demanding for the last five decades. The former Prime Minister, Narsimha Rao, went so far as to suggest, that the Congress Government would concede "Azadi, short of Independence" to meet Muslim separatism, at least half-way, exactly in the same manner as the Congress had offered to concede a Muslim State within India, when it accepted the Cabinet Mission Plan in 1946.

government in Jammu and Kashmir. There is a deep difference of opinion about the feasibility of a political package on 'greater autonomy' to the State; Hindus and the other minorities, about 46 percent of the population of the State, opposed to any restructurisation of the existing constitutional relations between the Union and the State, and the Muslims uncertain of whether the so-called package of autonomy would be acceptable to militant regimes as a basis for settlement with the Indian Govemment. Perhaps, the Govemment of India believes that it can substitute 'greater autonomy' for the 'right of self-determination', that the Muslim secessionist forces, militarised by Pakistan in 1989-90, have been demanding for the last five decades. The former Prime Minister, Narsimha Rao, went so far as to suggest, that the Congress Government would concede "Azadi, short of Independence" to meet Muslim separatism, at least half-way, exactly in the same manner as the Congress had offered to concede a Muslim State within India, when it accepted the Cabinet Mission Plan in 1946.

The acceptance of the separate identity of the Muslim majority provinces proposed by the Cabinet Mission Plan led to the partition of India in 1947. The acceptance of the 'autonomy of the State', which, evidently, is presumed to be based on exclusion of Jammu and Kashmir State from the Indian constitutional organisation, may lead to the second partition of India.

The Government of India appears to have overlooked the dangerous portent of forcing a restructurisation of the existing constitutional relations between the State and the Indian Union and exclude the State from the constitutional organisation of India, to push it back into the position of isolation in which it was placed from 1947 to 1954. In the new setting created by fundamentalisation of secessionist movements in the State and their militarisation by Pakistan, the exclusion of the State from the Indian constitutional organisation, which the demand for autonomy actually aims to achieve, will be a prelude to the disengagement of the State from India. The recognition of Jammu and Kashmir, as a separate Muslim identity, based upon the Muslim majority character of its population, repudiates the Indian commitment to secularism and integration of the Indian people on the basis of the fundamental right to equality. Perhaps, it is not fully realised that Muslimisation of Jammu and Kashmir, the only Muslim majority State in India, would eventually disrupt the foundations of the Indian political culture and threaten not only the secular values of the Indian nation but its unity as well.

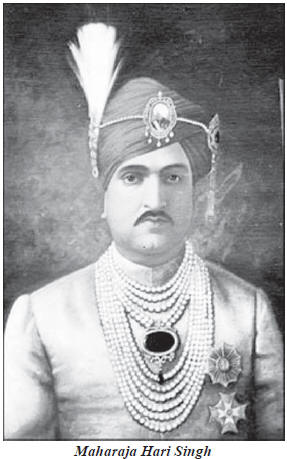

DISTORTION OF HISTORY

Maharaja Hari Singh, the ruler of Jammu and Kashmir State, signed the same standard form of the Instrument of Accession in October 1947, which the other Indian rulers signed to accede to the then Indian Dominion. The Instrument of Accession was evolved by the States Department, headed by Vallabh Bhai Patel, and was based upon the principles the Cabinet Mission had stipulated for the accession of the Indian States to the All India federation. All the rulers of the acceding States retained all the residuary powers of government and the Instrument of Accession they signed underlined the delegation of powers to the Dominion Govemment in respect of foreign affairs, defence and communications only. Among the other rulers, Hari Singh too retained the residuary powers of the government, and the Instrument of Accession he signed envisaged the delegation of powers to the Dominion Government of India in respect of foreign affairs, defence and communications. The Instrument of Accession did not bind any acceding State, including Jammu and Kashmir, to accept the future constitution of India.

No separate or special provisions were incorporated in the Instrument of Accession signed by Hari Singh and there was no precondition or agreement, specially accepted by the Government of India to any separate and special constitutional arrangement, to the exclusion of the other acceding States.

That the State Department of the Dominion Government, or the ruler of the State or the Congress leadership accepted any condition that Jammu and Kashmir would be provided a special constitutional position or any particular brand of autonomy or would be recognised as a separate Muslim identity, is a travesty of history. Neither Nehru, nor Patel gave any assurance to the Conference leaders that the Jammu and Kashmir State would be recognised as a separate constitutional entity because of the Muslim majority in its population.

When the invading armies of Pakistan were fast approaching Srinagar, the Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, Mehar Chand Mahajan, arrived in Delhi, with a request from Hari Singh for help against the invaders. Mahajan was instruced to inform the Government of India that the Maharaja had decided to accede to the Indian Dominion and accepted to transfer whatever authority he would be required to make in favour of the National Conference. Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah was in Delhi and neither he nor Nehru laid any conditions on Mahajan in respect of the future constitution of the State. Mahajan too did not make any commitment on the separate Muslim identity of Jammu and Kashmir or its autonomy. Nehru sought a substantial transfer of authority to the National Conference which was in consonance with the pledges that the Congress had given to the people of all Princely States. The Congress was committed to replace personal rule, which characterised the political organisation of the States, by representative institutions on the basis of administrative responsibility which was accepted for the reorganisation of the governments in the Indian Provinces. Jammu and Kashmir was not recognised as an exception here also.

After accession of the State to India, an Emergency Administration, headed by Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, was constituted by Hari Singh on 30 October 1947, to deal with the situation of crisis the invasion had created. In June 1948, The Emergency Administration was dissolved and replaced by an Interim Government, formed by the National Conference and headed by Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah.

Unfortunately lies have been multiplied during the last four decades to distort the history of those crucial years and lies are being retold to justify the treachery and blackmail, which characterised the atrocious process of forcing the exclusion of the State from the Indian constitutional organisation in 1950, when the Indian Constitution was adopted.

INSTRUMENT OF ACCESSION

The Instrument of Accession, which the rulers of the Princely States executed to join the Indian Dominion, reserved them the right to convene Constituent Assemblies to frame constitutions for their respective governments. The ruler of the Jammu and Kashmir also reserved the right to convene a Constituent Assembly to frame a constitution for his government. The Constituent Assembly of India, was by mutual consensus of the Premiers of the States and the representatives of the Constituent Assembly, entrusted with the task of evolving a model constitution, which the Constituent Assemblies of the States would follow in order to avoid any conflict between the Constitution of India and the constitutions of the States. Constituent Assemblies were convened in the Mysore State, the States Union of Saurashtra and the States Union of Travancore-Cochin.

In 1949, an extraordinary decision was taken by the Premiers of the States in a Conference held in Delhi. They decided to entrust to the Constituent Assembly of India the task of framing a uniform set of constitutional provisions for all the States. The constitutional provisions for the States, the Conference decided, would be incorporated in the Constitution of India.

The National Conference leaders did not accept the decision of the Premiers' Conference and insisted upon convocation of a separate Constituent Assembly for Jammu and Kashmir. Consequently, a Conference of the Conference leaders and representatives of the Dominion Government, in which Nehru and Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah participated, was convened in Delhi, shortly after the Premiers' Conference. A number of issues pertaining to the territorial jurisdiction of the Union, citizenship, fundamental rights and related safeguards, freedom of faith, emergencies arising out of war, rebellion and constitutional breakdown in the States, jurisdiction of the Courts, division of powers between the Union and the federating States, residuary powers between the Union and the federating States, the residuary powers and the institution of the Constituent Assembly in the State, came up for deliberation in the Conference. The Constituent Assembly of India had evolved provisions in respect of the territories of the Union, citizenship, fundamental rights, principles of State policy, jurisdiction of the courts and emergencies. The Constituent Assembly of India had also evolved a scheme of the division of powers between the Union and the States, which it proposed would replace the delegation of powers stipulated by the Instrument of Accession the acceding States had signed.

The Conference leaders stunned Nehru and the other Congress leaders when they refused to accept the application of any provisions of the Constitution of India to the State and instead insisted upon the continuation of federal relations between the proposed Union of India and Jammu and Kashmir on the basis of the Instrument of Accession. In other words they demanded the exclusion of the State from the consitutional organisation of India and its reorganisation into a separate political entity which would be aligned with the Union of India in respect of external relations, defence and communications. In fact, the National Conference demanded the restoration of control over the State army to the Interim Government, which they claimed, would undertake the defence of the State, after the Indian army was withdrawn. The Conference leaders proposed that

(i) the rule of the Dogra dynasty be abolished;

(ii) the State be excluded from the constitutional organisation of India:

(iii) the relations between the Union and the State be governed by the stipulations of the Instrument of Accession;

(iv) the control over the State army be transferred to the Interim Government of the State;

(v) the Interim Government would institute a separate Constituent Assembly to draw up a Constitution for the State.

The Indian leaders agreed to leave a wider orbit of authority to the State Government and accepted to vest the residuary powers with it. They agreed to the demand for the abolition of the Dogra rule, and the institution of a separate Constituent Assembly for the State. However, they refused to countenance the exclusion of the State from the Indian Union and its constitutional organisation. Nehru, evidently disconcerted with the proposals the Conference leaders made, told them that he could not accept to deprive the people of the State of the Indian citizenship, fundamental rights and the Directive Principles of State Policy which reflected the pride of the Indian people in the ideological commitments of their liberation struggle.

The National Conference harboured completely different views about the constitutional relations between the State and India. They visualised the State as a separate political entity with its own constitutional organisation, independent of the political organisation of India in respect of which the Union of India assumed the responsibility of defence, communications and external relations within the stipulations of the Instrument of Accession. The Conference leaders were motivated by a subtle consideration that since the execution of the Instrument of Accession by Maharaja Hafi Singh, which the Conference leaders derisively described as "Paper Accession", was subject to a plebiscite, the Muslims in Jammu and Kashmir, had assumed a veto over the accession of the State to India. To retain the Muslim right to veto on the accession of the State, the Conference leaders evaded any fresh Constitutional postulates and agreements with the Indian Union, which would replace the Instrument of Accession or would alter its consequences.

The atmosphere in which Delhi Conference was convened, was pervaded by a deep feeling of uncertainty. A month before the Delhi Conference was held, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah had thrown a bombshell in the Indian camp when he had told the correspondent of 'Scotsman', that the independence of Jammu and Kashmir would be the most suitable course to end the dispute over Kashmir. In case, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah maintained, Kashmir was able to establish good neighbourly relations with India and Pakistan, the two countries would settle down to peace and live as good neighbours.

The National Conference leaders made a tactical retreat mainly to bide time and an agreement was finally reached between them and the Congress leaders. The agreement stipulated:

(i) that Jammu and Kashmir would be included in the territories of Indian Union;

(ii) provisions of the Constitution of India in respect of citizenship, fundamental rights and related legal guarantees, Directive Principles of State Policy and the Federal Judiciary would be extended to the State;

(iii) the division of powers between the State and the Union of India would be governed by the stipulation of the Instrument of Accession and not the Seventh Schedule of the Indian Constitution;

(iv) the administrative and the operational control of the State army would remain with the Government of India;

(v) a separate Constituent Assembly of the State would be convened to draw up the Constitution for the State; and

(vi) the Constituent Assembly, after it was convened, would determine the future of Dogra rule.

The agreement was shortlived. Not long after the Conference leaders returned to Srinagar, they made public pronouncements that the Jammu and Kashmir State would not compromise on the issue of autonomy and the Constituent Assembly of the State would evolve a set of separate principles in regard to citizenship, fundamental rights, Principles of State Policy and elections. The Conference leaders gave ample expression to their reluctance to accept the inclusion of the State in the Indian Union and the application of any provisions of the Constitution of India to the State.

The issues came to a head when Gopalaswamy Ayyangar sent the draft constitutional provisions, he had drawn up for the State, to the Conference leaders for their approval. The draft provisions were based upon the agreement reached in Delhi in May 1949, between the representatives of the Government of India and the Conference leaders. After closed door deliberations, the Conference leaders placed the draft proposals before the Working Committee of the Conference. The Working Committee turned down the proposals promptly.

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah sent an alternate draft to Ayyangar which envisaged exclusion of the State from the Indian Union and its constitutional organisation. The draft stipulated the abolition of the Dogra rule and the reorganisation of the State into an independent political entity which would be federated with the Indian Union on the basis of the Instrument of accession. The draft proposed that the separate political identity of the State would be based upon the Muslim majority character of its population, its separate culture and history and the aspirations of its people for economic equality and political freedom which the Constitution of India did not enshrine.

The Conference leaders were particularly opposed to application of the provisions of the Constitution of India with regard to citizenship and fundamental rights to the State. They disapproved of all forms of safeguards which the provisions of the Constitution of India in respect of fundamental rights embodied, on the pretext that such safeguards would frustrate the resolve of the Interim Government to undertake economic, political and social reforms in the State. The real reasons for the Conference leaders to resist the application of the fundamental rights to the State were, however, different. The right to equality and the right to protection against discrimination on the basis of religion, the right to freedom of faith and the right to property enshrined by the Constitution of India, conflicted with the Muslimisation of the State, the Interim Government had embarked upon, right from the time it was installed in power. The Interim Government enforced the communal precedence of the Muslim majority in the government, the economic organisation and the society of the State with religious zeal. The discriminatory legislation, which devastated the non- Muslim minorities in the State, worst hit among them being the Hindus in the Kashmir Province, controverted the safeguards the Constitution of India envisaged against discrimination on the basis of religion.

Ayyangar received a jolt when the communication of the Conference leaders, along with the draft proposals drawn by Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, was delivered to him. On 14 October 1949, he had a long meeting with Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah and Mirza Afzal Beg in Delhi and tried to persuade them to adhere to the agreement they had accepted in the conference at Delhi, earlier in May. The Conference leaders did not relent and told Ayyangar bluntly that they would not accept the application of the Constitution of India to the State.

Ayyangar failed to face the Conference leaders with firmness. He made a vain bid to placate the Conference leaders by offering to exclude fundamental rights and related legal safeguards, from the provisions of the Constitution of India, which were proposed to be extended to the State in his draft. To his consternation, the Conference leaders rejected the modified draft as well. They informed Ayyangar that the National Conference would not accept the application of any provision of the Constitution of India, including the provisions with regard to the territories of the Union and citizenship and that it accepted only the Instrument of Accession as the basis of any relationship between the State and the future Union of India. When Nehru and other Indian leaders insisted upon the inclusion of the State, at least, in the basic structure of the Constitution of India, the Conference leaders broke off the negotiations and threatened to withdraw from the Constituent Assembly.

Fearful of a crisis the resignation of Conference leaders from the Constituent Assembly of India would create in Jammu and Kashmir and its repercussions outside India, Ayyangar beseeched them not to take any precipitate action which would adversely affect Indian interests in the Security Council. A breach with the Conference leaders, he believed, would undercut the support India had among the Kashmiri speaking Muslims who Nehru, still believed, would win the plebiscite for India. The Conference leaders, foxy and sly, used the United Nations intervention, ironically enough, invoked by India to secure the withdrawal of the armies of Pakistan from the occupied territories, to foist on the Indian leaders, a settlement which placed the State in a position outside the political organisation of India.

Nehru was abroad in the United States of America. Ayyangar met the Conference leaders and assured them that the Government of India would accept a constitutional position for Jammu and Kashmir outside the Indian constitutional organisation. He further assured them the Government of India respected the aspirations of the Muslims of the State, and therefore, would accept the institution of a separate Constituent Assembly of the State which would frame the Constitution of the State and also determine the future of the Dogra dynasty. The provisions of the Instrument of Accession, Ayyangar assured them further, would determine the Constitutional relationship between the State and the Union of India.

Ayyangar drew up a fresh draft in consultation with Mirza Afzal Beg. Abdullah pulled the strings from behind the scene. The revised draft, prepared by Ayyangar and moved in the Constituent Assembly of India, envisaged:

(i) no provisions of the Constitution of India, except Article 1, would be extended to the State;

(ii) the division of powers between the Union and the Jammu and Kashmir State would be limited to the stipulations of the Instrument of Accession;

(iii) a separate Constituent Assembly would be convened in Jammu and Kashmir to frame its Constitution;

(iv) the President of India would be empowered to vest more powers in the Union Government in respect of Jammu and Kashmir in concurrence with the State Government;

(v) the President would be empowered to modify the operation of the special constitutional provisions for the State on the recommendations of the Constituent Assembly of the State;

(vi) the State Government would be construed to mean, the Maharaja acting on the advice of the Council of Ministers appointed under his proclamation dated 5 March 1948."

The draft provisions were incorporated in Article 306-A of the draft Constitution of India. The draft Article 306-A was renumbered Article 370 at the revision stage.

Article 306-A was circulated in the Constituent Assembly on 16 October 1949. It came up for consideration of the Assembly the next day. Several members of the Constituent Assembly detected an error in the draft provisions, which Ayyangar had overlooked. The draft Article defined the State Government as the "Council of Ministers appointed under the Maharaja's Proclamation dated 5 March 1948." The members of the Constituent Assembly pointed out to Ayyangar that the definition of the State Government envisaged a perpetual Interim Government which would lead to the creation of an anomalous situation of excluding all successor governments from the provisions of the Constitution of India. Ayyangar modified the draft to remove the anomaly and redefined the State Government as the "person for the time being recognised by the President as the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir acting on the advice of the Council of Ministers for the time being in office under the Maharaja's proclamation dated the fifth day of March 1948."

The Conference leaders took strong exception to the change in the definition of the State Government. Mirza Afzal Beg threatened to move an amendment to the draft provisions of Article 306-A, seeking to alter the definition of the State Government.

Beg had actually sought to include provisions in the draft Article 306-A which envisaged a perpetual Interim Government in the State and which could be used as a lever against India in future. He and the other Conference leaders, were disconcerted with the inclusion of the State in the First Schedule of the Constitution of India and wanted some pretext to block the passage of the special provisions in the Constituent Assembly.

Ayyangar could not remodify the definition of the State Government, in view of strong reaction against it in the Constituent Assembly. He failed to persuade the Conference leaders to condescend to the modifications he had brought about in the draft. When Article 306-A came up for the consideration of the Constituent Assembly, the Conference leaders sulked away and did not join the deliberations on the draft provision till Ayyangar completed his speech. They sat glum when the draft provisions were put to vote and passed unanimously.

Immediately after the draft provisions were adopted by the Constituent Assembly, they sent a sharp rejoinder to Ayyangar demanding the rescission of Article 306-A as adopted by the Constituent Assembly, failing which they threatened to resign from its membership. Ayyangar was stunned. He sent a plaintive note to the Conference leaders entreating them not to take any action which would prejudice the Indian interests, and wait for Nehru's return. The Conference leaders did not resign from the Constituent Assembly, but as the days went by, they launched a surreptitious and widespread campaign to subvert the special provisions of Article 370.

Article 370

Article 370, in its original form, envisaged exclusion of Jammu and Kashmir State from the secular Constitutional organisation of India, and its reorganisation into a separate political identity based upon the Muslim majority character of its population. It imposed a limitation on the application of the provisions of Constitution of India to the State. The division of powers between the State and the Union was also limited to the stipulations of the Instrument of Accession. Article 370, was therefore, not an enabling act. It was, in fact, an act of limitation imposed on the application of the Constitution of India to the State, after the State was included in the First Schedule of the Constitution. The State was included in the First Schedule independent of Article 370.

CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF JAMMU AND KASHMIR

The Conference leaders sought to use the Constituent Assembly of the State to undermine the special provisions of Article 370 as well as the Instrument of Accession. The elections to the Constituent Assembly of the State were held in 1951. Seventy three of the Conference nominees were returned to the Assembly unopposed. Two of the remaining seats in the 75 member Assembly were also annexed by the National Conference.

In his inaugural address, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah claimed plenary powers for the Constituent Assembly to determine the final form of the Constitutional relations between the State and the Indian Union, which virtually sought to subject the special provisions envisaged by Article 370 to the verdict of the Assembly. He went further and asserted that the Constituent Assembly, its powers drawn from the people of the State, would determine future affiliations of the State in respect of its accession, in accordance with the options the Cabinet Mission Plan had reserved for the States. In categorical terms, he spelt out that the Constituent Assembly would determine whether the State would remain in India, accede to Pakistan or assume independence. The implications of his statement were clear. Article 370 would be rendered redundant after the Constituent Assembly had taken a final decision on the accession of the State and its constitutional relations with India.

The exclusion of the State from the Constitutional organisation of India and the insistence of the Conference leadership on the right to plenary powers for the Constituent Assembly, caused concern among the Hindus and the other minorities. The Hindus of Jammu reacted sharply against the exclusion of the State from the Indian Constitutional organisation, which they feared was a ploy to undo the accession of the State to India. They also opposed the abolition of Dogra rule, which they alleged would be used by the Interim Government to break the last link between India and the Jammu and Kashmir State.

The Hindus of the Kashmir Province, who bore the rigours of the Muslimisation of the State, also expressed strong disapproval of the Conference demand for a separate political organisation of the State. They had been devastated by the enforcement of Muslim precedence, and virtually reduced to a state of servitude. Their voice was stifled by the Conference gendarmes, who had taken over magistracies in the Valley in the aftermath of the invasion and dispensed justice in the name of Islam. The Conference leaders branded the Hindus as the traitors to the freedom of Jammu and Kashmir and accused them of having supported the Dogra rule in its depredations against the Muslims.

The Hindus made frantic appeals to the Indian Prime Minister and entreated Ayyangar not to accept the exclusion of the State from the Indian political organisation. They pleaded with the Indian leaders that the consequences of the isolation of the State and its reorganisation into a separate political organisation, governed by the commitment of the National Conference to the Muslimisation of the State, would have disastrous consequences in the long run.

History proved them right. Four decades after Article 370 was enacted, the rickety structure of the political instruments envisaged by it, crumbled under the onslaught of the Muslim secessionist forces, militarised by Pakistan. With that were wiped out the Hindus and the other minorities, along with the hollow slogans of secularism with which the successive governments of India had concealed the ugly face of Muslim communalism in the State.

The demonstrations made by the Hindus in Kashmir evoked little response from the Congress leadership. Blinded by the partition of India, which had been brought about by the Indian Muslims, rather than the British, they looked to the Muslims of Kashmir as the sole guarantors of secularism in India. They denounced the Hindus and other minorities for allegedly seeking to communalise the traditionally tolerant community of the Muslims and applauded the National Conference for its demand to secure the exclusion of the State from the secular political organisation of India on the basis of the Muslim majority character of its population

The National Conference used the Indian State to defend Jammu and Kashmir from the invading armies of Pakistan in 1947. After that was accomplished, they sought to use the United Nations intervention to pull out the State from India. In August 1953, the Interim Government was dismissed and a second Interim Government headed by Bakhshi Gulam Mohammad installed in its place. In 1954, the limitations imposed upon the application of the Constitution of India to the State were partially lifted by a Presidential proclamation, in respect of citizenship, fundamental rights, Government of India, division of powers, federal judiciary and elections to the Parliament. Subsequent proclamations extended more provisions of the Constitution of India to the State. The application of the provisions of the Constitution of India, however, were subject to reservations and exceptions, which mutilated their real content.

TERRORISM AND AUTONOMY

In the broad background of terrorist violence which has ravaged the State for the last six years, the demand for greater autonomy and the wild assurances of the successive Indian Governments to support it, has an ominous portent. The restoration of the 1953 status, which is presumed to be the bottom line the autonomy of the State will necessitate restructurisation of the existing Constitutional relations between the State and the Union of India and the withdrawal of the provisions of the Constitution of India, extended to the State, following the Presidential proclamation of 1954. The restoration of the separate political identity of the State on the basis of the Muslim majority character of its population will reinforce the Muslim claim to a veto on the accession of the State to India.

The insistence on (i) a safer zone to protect the Muslim minority from the dominance of the Hindu majority in India, and (ii) the right of the Muslims to reconstitute the Muslim majority provinces to form a Muslim State, were the two basic planks on which the Muslim League secured the partition of India. The creation of an autonomous state of Jammu and Kashmir placed outside the political organisation of India, will go half-way to substantiate Pakistan's claim on Kashmir. With militant guns booming in the background, India will, sooner or later, be forced to accept a settlement which is acceptable to Pakistan.

The militarisation of Muslim secessionist forces and their reorientation to Pan-Islamic fundamentalism has added a new dimension to the Muslim separatism in Jammu and Kashmir. The consolidation of Pan-Islamic fundamentalism as a basis for a global strategy to unify the Muslim nations into an independent power in the world, with Pakistan as one of its focal centres, threatens the whole northern frontier of India.

The demand for autonomy reflects the unconcealed satisfaction with which its proponents are using the ground earned by militants, to pull out the State from the Indian political organisation. With the Hindus in exile, there is no one left in Kashmir to weep for India. On a midnight hour, sometime in future, India might once again awaken to the reality of a second partition.

Kashmir: The Bitter Truth

by Dr. M. K. Teng, C. L. Gadoo

(Joint Human Rights Committee WA-88, Shakarpur, Delhi - 110092)

India That the Princely States of India, including Jammu and Kashmir State, were on the agenda of the partition of India in 1947, is a travesty of history

and a part of the diplomatic offensive, Pakistan has launched to mislead the international opinion about its claim to Jammu and Kashmir. The matter of the fact is that the lapse of Paramountcy was a consequence of the dissolution of the British empire in India and the political imperatives of the authority, the British Crown exercised over the princely States. The withdrawal of the Paramountcy was not a concomitant or a consequence of the Indian partition, and neither the June 3 Declaration of 1947, nor the independence of India Act, embodied any provision by virtue of which the partition of India affected the Princely States or the British Paramountcy.

and a part of the diplomatic offensive, Pakistan has launched to mislead the international opinion about its claim to Jammu and Kashmir. The matter of the fact is that the lapse of Paramountcy was a consequence of the dissolution of the British empire in India and the political imperatives of the authority, the British Crown exercised over the princely States. The withdrawal of the Paramountcy was not a concomitant or a consequence of the Indian partition, and neither the June 3 Declaration of 1947, nor the independence of India Act, embodied any provision by virtue of which the partition of India affected the Princely States or the British Paramountcy.

The British colonial empire in India was divided into two separate and different political organisations, the British India constituted of the British Indian Provinces and the India of Princes. The British India was directly governed by the British Government through the Governer-General of India, with each of the Provinces in charge of a Provincial Governor, who in the old British tradition, administered the Provinces, with the help of the Indian Civil Service.

The Princely States were ruled by local potentates, who had carved their independent fiefs and kingdoms in the long and atrocious process of the British expansion in India. Five hundred and sixty two in number, the Indian States formed a conglomerate of widely disparate identities in their territories, population and government. The Princes were British feudatories, who accepted the supremacy of the British Crown, which was symbolized in the person of the Crown Prince, or the Viceroy of India. The relations between the British Crown and the States were governed by what the British called, the "Paramountcy'. Paramountcy in real terms, described the extent of the authority the British exercised over the States.

Apparently, the rulers of the States were vested with the powers to rule their States, but in actual practice, the States were administered by the British officers, whose functions were determined by the Viceroy, the Political Department of the Government of India and the British Residents posted in the States. The Princes represented the best of the oriental splendour, with their treasuries held by the British, and their privy purses plentifully provided.

The Partition of India, which loomed larger on the horizons after the failure of the Cabinet Mission and the campaign of "Direct Action" launched by the Muslim League, suddenly pushed the States into the fore-front. Interspersed in the British Indian Provinces, the States were spread over more than one third of the territory of India and constituted about a hundred million people, almost a quarter of the population of India.

The British, the Muslim League as well as the Indian National Congress, for their own interests, did not favour the inclusion of the Princely States, in the constitutional reforms, the Indian liberation movement idealised. The British held the States as a personal preserve, protected the Princes against their people and harnessed the resources of the States to promote the interests of their empire. The Princes, of their privileges and unrestricted power over their subjects, supported the British, to isolate themselves from any constitutional change which prejudiced their position.

The Indian renaissance evoked a widespread response in the Princely States, and the liberation movement in India received as much support from the people of the States as it did in the British Indian Provinces. In fact, the revolutionary struggle, which followed the Swadeshi Movement in the aftermath of the stormy session of the Indian National Congress at Calcutta in 1906, grew in the States, where numerous revolutionaries received quarter.

The Congress leaders, however, on the insistence of the Princes and the Muslim League, withdrew its movement from the States, and till almost the end of the British rule, refused to integrate the people's movements in the States avowedly inspired by the liberation of India, with the national struggle against the British in the Provinces. The Congress leaders were neither prepared to displease the Princes, who were the mantle of Indian nativity, nor did they dare to disregard the Muslim League leaders, who made the exclusion of the hundred million people of the Princely States, a precedent condition to any compromise on the constitutional reforms in lndia. The League leaders knew that the inclusion of the people of the States, predominantly Hindu, would reduce the weightage of the Muslim population in the British India in any future scheme of constitutional change.

Throughout the long decades, the Indian national movement evolved, the Congress leadership remained divided on the anti- imperialist struggle in the States and the All-lndia Congress Committee did not formalise its opinion on the States till the Udaipur session of the All-India States People's Conference held in 1946. By that time, however, much precious time had been lost. The States had almost been isolated from the mainstream of the national movement and stood vulnerably exposed to the machinations of the British, the Muslim League and the Princes to balkanise India.

The Muslim League policy on the States was more involved and shifting, which concealed the designs of the League to grab the Muslim ruled Hindu majority States as well as the Muslim majority States for the separate Muslim State of Pakistan, the League demanded for the Muslims in India. The All-India States Muslim League, an appendage of the Muslim League, constituted to co-ordinate the Muslim movements for Pakistan in the States, demanded in 1940, the integration of all such Indian States in the Muslim homeland of Pakistan as were ruled by the Muslim rulers as well as all such States .as were inhabited by Muslim majorities. The Lahore Resolution of the League, claimed a separate homeland for the Muslims in India, which was constituted of the Muslim majority Provinces of Sindh, the Punjab, Bengal, North-west Frontier, the Chief-Commissioner's Province of Baluchistan and the Hindu majority Province of Assam for its geographical contiguity to Bengal, besides the Princely States which were either ruled by the Muslim rulers or populated hy Muslim majorities.

The Congress awoke to the dangerous consequences of the isolation of the States almost after it had virtually accepted the partition, when it realised that the British, in collaboration with the Muslim League, were conspiring to break up India into several imbecile political entities with the Muslim State of Pakistan strategically placed at their epicentre. That was precisely what Jinnah, Conrad Corfield, and the Political Department of the Government of India visualised as the future constitutional composition of India. The Cabinet Mission Plan also, by and large, envisaged the division of India into several political identities which were confined within the territorial jurisdiction of a united Indian Dominion. The Cabinet Mission precisely accepted the separate identity of the Princely States and rejected any proposition to transfer the Paramountcy to the federal government. The Mission insisted upon the agreements between the federal authority and the Princely States, as a basis for any future relations between the States and the Indian Union which would follow their accession and withdrawal of the Paramountcy.

At the time, when the British and the Muslim League settled down to decide the fate of India, the Congress turned to the people in the States, whom they had neglected throughout the long history of Indian struggle against the British. Once again the Congress leaders fell prey to their own indecision and made a half-hearted plea for the right of the people of the States to determine their future. Not backed by conviction, the Congress demand made little impression upon the British and the League. The Princes were disparaged and opposed the right of the people in the States to determine their future. The League leaders turned the bend at the most appropriate time and in an astute move, pledged their support to the British designs to exclude the States from the constitutional arrangements envisaged by the partition and the withdrawal of the Paramountcy, to restore to the Princes, the powers which the British Crown exercised over them. The Muslim League realised that most of the States were populated by Hindu majorities and any arrangements to transfer Paramountcy to the two Dominions, would definitely place them in India. After the lapse of the Paramountcy, the Muslim League shared the optimism of British about independence of the States and their eventual alignment with the Muslim State of Pakistan, as a counterweight against India.

The Congress resolve, having been broken by the partition and the Congress leaders, still groping for a new rationale of the Indian freedom, after their basic commitment to the unity of India was abandoned, did not stick to their demand for the right of the State's people to determine the future disposition of the States. Instead they acquiesced, without demur, with the British proposals to terminate the Paramountcy and restore the Princes the powers to decide their future affiliations with the two successor Dominions of India and Pakistan. The States were thus removed from the agenda of the Indian partition on the insistence of the British, the machinations of the Muslim League as well as the unconditional acceptance of the lapse of Paramountcy by the Congress.

The conspiracy proved to be deeper and though the British Government refused to accord the status of British Dominions to the Princely States, it left the door open for separate negotiations with their rulers. Mountbatten informed the Princes, that he would forward to the British Government any requests from anyone of them to establish direct relations with Great Britain.