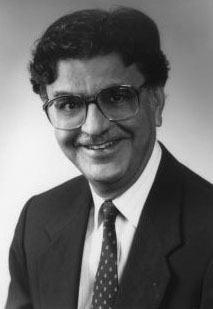

Braj B Kachru

Professor Braj B. Kachru is the Director of the Centre for Advanced Study at the University of Illinois, Champaign, USA. He is the world's leading scholar inthe field of world Englishes; he has pioneered, shaped, and defined the linguistic, socio-cultural and pedagogical dimensions of cross-cultural diffusion of English.

Professor Kachru is author or editor of 20 books, including the prize-winningThe Alchemy of English: The Spread, Functions and Models of Non-Native Englishes, associate editor of the acclaimed The Oxford Companion to the English Language and Contributor to the Cambridge History of the English Language. In addition, he has written over 100 research papers, review articles and reviews on Kashmiri and Hindi languages and literatures, and theoretical and applied aspects of language in society. Kachru sits on the editorial boards of eight scholarly journals, and is founder and co-editor of the journal World Englishes. He has chaired many national and international committees and led several organisations, including the American Association for Applied Linguistics. Among his many awards is the Duke of Edinburgh Award (1987).

Professor Kachru holds appointments in linguistics, education, comparative literature and English as an international language. He is a Jubilee Professor of Liberal Arts and Sciences and was head of the Department of Linguistics for 11 years, director of English as an International Language for six years, and director of the Linguistic Institute of the Linguistic Society of America (1978). He has had fellowships from the British Council, the East-West Centre and the American Institute of Indian Studies. He has held visiting professorships in Canada, Singapore and India.

Articles

A Love for Language

Braj Behari Kachru, famous for his theories on how native languages shaped English, grew up in the Himalayan region of Kashmir, northern India, where he spoke only Hindi and Kashmiri until he was 16. |

A Love for Language

Cultural forces defined this linguist and his language.

There are books everywhere in his small office at the UI, spilling from bookshelves onto worktables, the plush visitor's chair, and the floor. Even his computer monitor wears a journal, like a hat. A self-confessed book addict, he reads and rereads them all. Every now and then he writes one of his own and the international academia sits up, as it has for three decades. Indeed, books are his passion. But language is his life.

Braj Behari Kachru is a well-known figure in LAS's Department of Linguistics. Since arriving on campus in 1965, Kachru has written more than a dozen influential books, coedited the trailblazing journal, World Englishes, and attained some of the University's highest honors, such as being designated a Jubilee Professor and serving as head of the Linguistics Department and director of the Center for Advanced Study. His research specialty, sociolinguistics, is one of the department's research pillars.

Though now a world-renowned authority on the English language, the India-born Kachru spoke only Hindi and his mother tongue, Kashmiri, until he was 16. But he had the advantages of a highly educated family that was part of the Kashmiri Pandit community renowned for its achievements in language, literature, art, and, above all, education. Indeed, the term "Pandit" means "revered teacher" in Sanskrit. Kachru's brother and father, too, were educators.

"It's a complex situation," says Kachru, reflecting on how his heritage has shaped his own pursuits. "Minority communities need to be superachievers to have security in jobs and money. Since they are a minority, they do not find it easy to preserve their identity." Culture and identity are critical to him and to his linguistics.

Kachru was born in 1932 in Srinagar, a city in the Himalayan region of Kashmir, into a lively, extended family that eventually consisted of 18 siblings and cousins. Under this joint family system, the parents share in all the children's upbringing and treat them equally; however, Kachru was brought up under special circumstances. His mother died when he was five, after which Kachru's father and aunt reared him. Because he was diagnosed with a rheumatic heart—later proven wrong—he was not allowed to exert himself physically nor attend school with his cousins. Instead, he was tutored in art, music, and Hindi. He delighted in the stream of famous educators, poets, critics, and academics who visited his home to share his father's love of Kashmiri literature.

In 1947, at 15, he began working toward a bachelor's in English. Later, he received his master's in English from the Institute of Linguistics in the western city of Poona, part of the Rockefeller Foundation's Postgraduate and Research Institute.

"That's where he got interested in phonetics, and that's where we met," says Kachru's wife, Yamuna, who was a UI linguistics professor until retiring last year.

From Poona, Kachru headed to Britain to begin a doctorate in Indian English at Scotland's University of Edinburgh, where he met Robert Lees, who offered him a position at the UI starting in 1963. Kachru accepted, but first returned to India for a year to establish a linguistics program in the Department of English at Lucknow University. Yamuna joined Kachru at Illinois in 1969.

In the early 1980s he coined the term and philosophy for which he is most famous: "world Englishes," which describes the dispersion of English across the globe. "The term was controversial in the beginning," says Marguerite Courtright, a Kachru student and teaching associate in the Department of English as an International Language. "There were purists who believed that there should be only one standard English—British English. The rest, they said, were deviant. The concept of world Englishes allows for varieties in English usage; it allows for diverse Englishes."

Kachru postulated that "there were many varieties of English molded by the influences of the different native languages. World Englishes follow different rules from the Standard British English," Courtright explains. In India, as in most post-colonial nations, speakers "weave both English and the native language into their conversations without consciously realizing which language they are using," says Kachru.

Though he still feels umbilically connected to India and visits each year, Kachru's family has broken with their homeland of Kashmir. In 1985, Jihadic Muslims began a policy of ethnic cleansing. "No Pandit lives in Srinagar anymore," says Kachru. "They...are migrants in their own country." As happened to Kachru when he left India, his family is now struggling to retain their cultural and linguistic traditions as they redefine them.

by Anupama Chandrasekhar, a graduate student in the College of Communications

Summer 2001

Source: http://www.las.uiuc.edu/alumni/news/01summer_love.html

Granny Lalla

by Braj B. Kachru

Kashmir has produced many saints, poets and mystics. Among them, Lal Ded is very prominent. In Kashmir, some people consider her a poet, some consider her a holywoman and some consider her a sufi, a yogi, or a devotee of Shiva. Sume even consider her an avtar. But every Kashmiri considers her a wise woman. Every Kashmiri has some sayings of Lalla on the tip of his tongue. The Kashmiri language is full of her sayings.

Kashmiri Hindus and Muslims affectionately call her "Mother Lalla" or "Granny Lalla". She is also called "Lallayogeshwari". Some people call her Lalla, the mystic.

It is said that Lal Ded was born in 1355 in Pandrethan to a Kashmiri Pandit family. Even as a child, Lalla was wise and religious-minded. When Lalla was twelve years old, she was married. Her in-laws lived in Pampur. The in-laws gave her the name Padmavati. Her mother-in-law was very cruel. She never gave her any peace. It is claimed that her mother-in-law used to put a stone on Lalla's plate (tha:l). She would then cover the stone with rice so that people would get the impression that Lalla had a plateful of rice. Lalla would remain half fed, but would never complain about her mother-in-law. Her father-in-law was a good man and he was kind to her, but her mother-in-law made her miserable. She would even speak ill of Lalla to her husband. Poor Lalla knew no happiness either with her husband or with her mother-in-law.

When Lalla was twenty-six she renounced the family and became a devotee

of Shiva. Like a mad person, she would go around naked.

She became a disciple of Sidh Srikanth. She would only keep the company of sadhus and pi:rs. She did not think in terms of men and women. She would claim that she had yet to encounter a man, and that is why she went about naked. But when she saw Shah Hamdan, she hid herself saying: "I saw a man, I saw a man."

Why is Lalla so famous in Kashmir? She was illiterate, but she was wise. Her sayings are full of wisdom. In these sayings, she dealt with everything from life, yoga, and God to dharma and a:tma:. Her riddles are on the lips of every Kashmiri.

The exact date of Lalla's death is not known. It is claimed that she died in Bijbehara (vejibro:r). People like Granny Lalla do not really die. Lal Ded is alive in her sayings and in the hearts of Kashmiris.

The sayings of Lalla number around two hundred.

Five Sayings of Lal Ded

I

By a way I came, but I went not by the way.

While I was yet on the midst of the embankment

with its crazy bridges, the day failed for me.

I looked within my poke, and not a cowry came to hand

(or, atI, was there).

What shall I give for the ferry-fee?

(Translated by G. Grierson)

II

Passionate, with longing in mine eyes,

Searching wide, and seeking nights and days,

Lo' I beheld the Truthful One, the Wise,

Here in mine own House to fill my gaze.

(Translated by R.C. Temple)

III

Holy books will disappear, and then only the mystic formula will remain.

When the mystic formula departed, naught but mind was left.

When the mind disappeared naught was left anywhere,

And a voice became merged within the Void.

(Translated by G. Grierson)

IV

You are the heaven and You are the earth,

You are the day and You are the night,

You are all pervading air,

You are the sacred offering of rice and flowers and of water;

You are Yourself all in all,

What can I offer You?

V

With a thin rope of untwisted thread

Tow I ever my boat o'er the sea.

Will God hear the prayers that I have said?

Will he safely over carry me?

Water in a cup of unbaked clay,

Whirling and wasting, my dizzy soul

Slowly is filling to melt away.

Oh, how fain would I reach my goal.

(Translated by R.C. Temple)

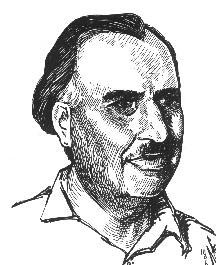

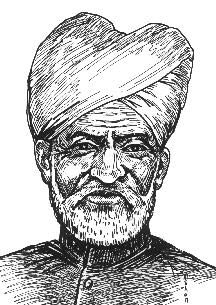

Master Zinda Kaul

Pandit Zinda Koul is a well-known poet of Kashmir. In Kashmir, his students and friends used to call him 'Masterji'. He came to be called 'Masterji' because he used to teach many Kashmiris, both in school as well as at his home. He died in Jammu in the winter of 1965.

In the beginning 'Masterji' did not write in only Kashmiri. He wrote poetry in Persian, Hindi, and Urdu, as well. Masterji's poetry has been published in all these four languages. However, he made his name by writing in Kashmiri.

In the beginning 'Masterji' did not write in only Kashmiri. He wrote poetry in Persian, Hindi, and Urdu, as well. Masterji's poetry has been published in all these four languages. However, he made his name by writing in Kashmiri.

His well-known book in Kashmiri is Samran. It was first published in Devanagari, and later the government had it printed in the Persio-Arabic script. The Sahitya Academy of India gave Pandit Zinda Koul an award of five thousand rupees for this book. Masterji received this award in 1956.

Masterji had to face many difficulties in his life. He was a school teacher for a long time. After that, he worked as an ordinary clerk.

Masterji started writing in Kashmiri in 1942. In his Kashmiri poetry, he has written primarily on devotion and peace. His poetry was greatly influenced by Lal Ded and Parmanand.

Masterji composed poetry only for (his own) pleasure. Those who know say that Masterji's poems in Kashmiri were better than those in Hindi and Urdu. Masterji translated the poems of the famous Kashmiri poet Parmanand into English. These poems have been published in three volumes. Kashmiri poetry suffered a great loss upon Masterji's death.

Compulsion (majbu:ri)

by Zinda Koul 'Masterji'

One would cry and not restrain the tears,

But crying is of no avail,

Shedding incessant tears is of no avail,

And knocking one's head against

boulders is of no avail.

And knowing that there is none to heed,

Why this urge to plead!

Why dash darts into the void!

Mere compulsion! Mere helplessness!

The body is consumed minute by minute,

suppressed by hunger and thirst and cold,

chained by ailments and kith and kin

depressed by constant worries and woes.

And once these worries cease to exist,

the body is tempted and lured

by numberless temptations.

The restless mind is without any peace

for something has obsessed it.

Without the encounter with the Good,

Without the realization of the Good,

The mind is searching for something lost

like a person drunk in sleep.

More affliction of desire and body!

Our ears have heard,

Our hearts have believed,

that sometime, somewhere, someone

caught a distant glimpse of Him.

We pine for Him; we long for Him,

For we think he is sulking from us

hiding under the bushes.

Indeed, love is a painful obsession!

I ask

The one who is hidden far and away,

The one who gives us a deaf ear,

Does he ever enquire how we are?

Does he ever recall where we are?

Does he ever ask himself,

"I wonder what is the lot of those

Whom I put in the dismal dark,

Whom I let loose

Over the hills, over the streams, over the woods?"

Indeed, beauty has no compassion!

We could argue,

"Why expect love from the loveless?

Why expect fruit from a willow?

If you do not know his whereabouts,

How can you plan his search?"

But heart will not retract the steps

For how can one chain the air!

For how can one blame the heart!

Love is not a child's play!

It is the sound from within;

It is like the fragrance of the musk.

The musk deer hunts over hills and dales

looking for something that is within him.

The heart is like the musk deer, searching

without that which is within.

The fragrance of the dear one pulls him out

with eyes shut and hands down.

He is playing the game of hide and seek,

appearing here and appearing there.

Once the moth has seen the lamp afar,

how can it stand still?

It must chase the light with frenzy

(Even though the light is not seen).

It must tear through the seven robes of wisdom.

Beauty is not mere enchantment!

Mere compulsion! Mere helplessness!

Mere affliction of desire and body!

Indeed love is a painful obsession!

Indeed beauty has no compassion!

Love is not a child's play!

Beauty is not mere enchantment!

Dina Nath Nadim

by Braj B. Kachru

The death of Mahjoor and Masterji closed one phase of Kashmiri poetry. With Nadim's poetry, a new phase was introduced. Some people claim that Kashmiri poetry is currently passing through an era which may be termed "the Nadim era".

Nadim was born in Srinagar in 1918. He grew up in poverty. His father died when he was a child, and his mother raised him by herself. His mother had a great influence on him. She was illiterate, but very wise. While working at the spinning wheel, she would recite Lal Ded's sayings to Nadim.

he was a child, and his mother raised him by herself. His mother had a great influence on him. She was illiterate, but very wise. While working at the spinning wheel, she would recite Lal Ded's sayings to Nadim.

Nadim pursued his studies in great poverty and hardship. He received his B.A. degree in 1943 and obtained his B.T. degree in 1947.

From his childhood, he was interested in politics, freedom and progressivism. He was deeply influenced by the ideas of Bhagat Singh. His poetry is full of these ideas. The following is illustrative:

Burn and burn like a colorful field of la:liza:r!

Roar and roar like a waterfall!

You are fire

A furious fire of burning youth

Come out

And cross the hills and dales

Raise a storm!

Be a storm!

Another specimen is:

Why should the share of a laborer

be taken by a capitalist?

Why should a honey bee

circle the flowers and take away their honey?

Nadim introduced various poetic styles into Kashmiri. He was the first Kashmiri poet to write in blank verse, bi g'avini az, "I Shall Not Sing Today", is a good example of it.

In the beginning, Nadim composed poetry in English, Hindi, and Urdu. But then he wrote only in Kashmiri. Nadim used the Kashmiri language in his poetry with great grace and craftsmanship. He depicted the beauty and the poverty of Kashmir in all of his poetry. The following is an example:

A lost stray cloud

Floating aimlessly with the moon

As if a beggar woman holds a leftover lump of watery rice

In the corner of her headcover.

Nadim has also composed poetry in the folkstyle. In these folk poems, he has portrayed the dreams and longings of Kashmiris. The following is illustrative:

ya: sa:hi hamda:n,

ya: sa:hi hamda:n.

Are we human?

Who says human!

The winter is ahead of us

The pocket is moneyless

The hovel is roofless

And the law is chasing us

Do you care?

I don't care!

ya sa:hi hamda:n,

ya: sa:hi hamda:n.

For several years Nadim taught at the Hindu High School. After independence, he was appointed the Assistant Director of Social Education. In 1971, the Russian government gave him the Nehru award. He has also been a member of the Sahitya Academy. He has travelled to Russia, China, and some other countries as well, Nadim has been greatly influenced by communism and by progressive writers.

His poetry has contributed to Kashmir's struggle for freedom. Nadim also wrote the first opera in the Kashmiri language, entitled, bombir ti yembirzal "The Bumblebee and the Narcissus".

Nadim has greatly influenced the young Kashmiri poets of today. Kashmiri poetry is still going through the Nadim era.

The Song of a Boatwoman from Dal Lake

by Dina Nath ' Nadim '

I got these crisp and fresh from the dal

hay valay, come and buy! hay valay, come and buy!

These are tiny eggplants, and these are round gourds,

hay valay, come and buy! hay valay, come and buy!

These are peppers, and these are brinjals.

The brinjals are like pitchers of wine

banging their heads in this boat of mine.

hay valay, come and buy! hay valay, come and buy!

The crisp bundles of radishes are glittering

in the shade of weeds,

The red marsh turnip is blushing like a blushing beauty

as if the dawn has blossomed into flowers.

hay valay, come and buy! hay valay, come and buy!

May dust fall on you! Stop it!

You have taken enough now.

I know, dear lady, I cannot blame you,

for the high prices are crushing us all now.

Let me go!

Come on, lend me a hand with this basket

I really must go now.

hay valay, come and buy! hay valay, come and buy!

What can I tell you, dear lady,

My child was born only last Thursday.

Though I didn't feel up to it, I dragged myself out

and left my little one behind.

It was painful to leave him away from me.

hay valay, come and buy! hay valay, come and buy!

My little one!

My little one is pale like a radish,

My little one is pale like jasmine,

My little one is naked and nude, shivering and cold

like a lump of ice.

My little one is crying and crying,

the tears roll down from his eyes

like drops rolling down from lotus leaves.

hay valay, come and buy! hay valay, come and buy!

My little one's nose is like a lotus seed,

Just like his father's nose;

My little one's face is tiny,

just like his mother's face.

To us both he is like a lotus,

sprung from the mud of dalay hay.

hay valay, come and buy! hay valay, come and buy!

Lo' I seem to hear a baby cry;

Lo' I seem to feel a sensation in my breast.

My heart doesn't seem to be here now,

Dear lady, I must really go now.

hay valay, come and buy! hay valay, come and buy!

Kaeshir Ka:ngir

In a typical koshur household, the kangir continues to be the main, inexpensive source of keeping an individual warm during the winter months. A kangir is made up of two parts. The outer part is an encasement of wicker. Inside, there is an earthen bowl-shaped pot called a kondul. The kondul is filled with tsini (charcoal) and embers. A medium sized kangir holds about a pound of tsini, and its fire lasts for over six hours. Many Kashmiris fill a kangir with toh (chaff) or (guh') lobar (dry cowdung). A kangir is a constant comapnion of Kashmiris during the winter months. It is normally kept inside the Kashmiri cloak, the ph'aran, or inside a blanket if the person does not wear a ph'aran. If a person is wearing a jacket, it may be used as a hand-warmer.

Mahr'ni Kangir

The origin of the kangir is not known. Knowles (1885) makes the following observation:

It has been suggested that the Kashmiris learnt the use of the k'angar from the Italians in the retinue of the Mughal Emperors who often visited the valley, but no reliable particulars have as yet been ascertained.

In Kashmiri folklore the kangir has occupied a prominent place. In the following poem we see the role of the kangir in a Kashmiri's life. (see J. H. Knowles, A Dictionary of Kashmiri Proverbs and Sayings, Bombay, 1885, p. 128)

ma:g o:y dra:g vothuy, ka:gri:,

pha:gun o:y za:gun tso:y, ka:gri:,

tsithir o:y mithir p'oy, ka:gri:.

vah'ak o:y rah'akh kati:, ka:gri:,

ze:th o:y bre:th gayakh, ka:gri:,

ha:r o:y la:r leji:, ka:gri:,

sra:vun o :y ya:vun su:ruy, ka:gri:,

ba:dirp'ath o:y vadir peyi:, ka:gri:,

a:sid o:y ka:sid su:zmay, ka:gri:,

ka:rtikh o:y na:ritikh lazmai, ka:gri:,

mojiho:r o:y koji lajay, ka:gri:,

poh o:y toh lodmay, ka:gri:.

A free translation of the above poem is given below. The kashmiri months, like ma:g and pha:gun, roughly correspond to the Christian calendar, January and February. However, there is no one-to-one correspondence.

ma:g came and you were hard to get, hay ka:gri:,

pha:gun came and a plot was laid against you, hay ka:gri :,

tsithir came and no one cared about you, hay ka:gri:,

vah'ak came and there was no place for you, hay ka:gr:i :,

ze:th came and you became useless, hay ka:gri:,

ha:r came and you were chased away, hay ka:gri:,

shra:vun came and your youth disappeared, hay ka:gri:,

be:dirp'ath came and sickness came to you, hay ka:gri:,

a:shid came and I sent you a messenger, hay ka:gri:,

ka:rtikh came and I put some embers in you, hay ka:gri:,

mojiho:r came and we became concerned about you, hay ka:gri:,

poh came and I filled you up with toh, hay ka:gri:,

The mahr'ni kangir is specially made for brides. On the first he:rath (Shivratri) after getting married, a bride brings a specially decorated kangir to her in-laws' house. These have elaborate ornamentation and usually have a silver tsa:lan. The mahr'ni kangir are not terribly comfortable because of their size, but they are extremely attractive and used essentially for decoration.

The tsa:lan looks like a small 'cake server' and is used to turn the coal inside a kangir in order to increase the heat. It is usually tied to a round wicker hook on the back of the kangir. The expensive kangri have silver tsa:lni with silver chains. An inexpensive kangir has a wooden tsa:lan attached by a string.

The sur' kangir is a small kangir specially made for small children. These vary in their size.

The kondul is a bowl-like pot which holds the tsini, charcoal, and tyongal. The kondal (plu.) vary in size according to the size of the kangir.

The term tsini means charcoal in general, but for the kangri, a special type of charcoal is used. People usually prefer charcoal of bo:ni (chinar) leaves.

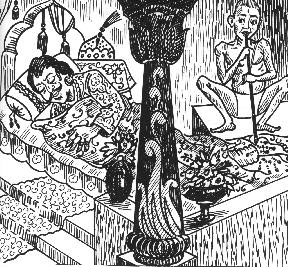

Mahadev Bishta: A Clever Thief

by Braj B. Kachru

Kashmiri mothers often tell their children the stories of Mahadev at bedtime. It is said that during the reign of Maharaja Partap Singh, Mahadev was considered the leader of thieves in Kashmir. He was never caught in the act of stealing. Mahadev had perplexed both the police and the government. Whenever Mahadev went out to steal, he would do so like a cat, without making a sound. They say that is why he was called Mahadev bishta. Kashmiri children refer to a cat as bishti. Mahadev would even mew to make people think that it was a cat. They would shout "bishti, bishti" - a sound made to scare away cats - while Mahadev took off with the loot.

Mahadev bishta: A Clever Thief

It is indeed a fact that Mahadev was a well-known thief. It is also true that he would rob people of their property and wealth. But, in spite of that, people used to sing his praises. The people loved Mahadev because he would steal from the wealthy to provide for the needy.

There is a particularly well-known story about Mahadev. One day the thieves decided that even though Mahadev was, without a doubt, their leader, he would still have to undergo a test. In a meeting, they also agreed upon the way he would be tested. We shall now tell you the story of this test.

One day Mahadev was invited to a gathering of all the thieves. One thief stood up and addressed Mahadev thus: "Hey, Mahdevju:, we all consider you to be our leader. We are all in awe of you. But, in order to prove your superiority, we would like you to take a test. If you agree, it will enhance your reputation and our trust in you will increase." Mahadev became very serious and replied: "Yes, of course, I am ready for a test." As soon as the thieves heard this reply, they blushed. One thief slowly stood up and said: "All right, Mahdevju:, we want you to make our Maharaja take off his trousers. These trousers should then be presented to this gathering. The Maharaja should know nothing about it " Mahadev smiled and said: "All right, if that is what you want, so be it. It is not a difficult task." On hearing this the thieves were delighted and the conference of thieves came to an end.

After this it took Mahadev four or five days to think. He went to Shergadi to observe several things. First, he found out the location of the Maharaja's bedroom, and the location of the palace guards. He also found a way to reach the Maharaja's bedroom without causing suspicion. After observing all these things, he started his preparations.

First, Mahadev went out and filled a piece of reed with vicious red ants. Then he came home and had his body massaged with oil. He then put on a lango:t(loincloth) and looked at himself in the mirror. He was very pleased with himself . And with a mischievous smile, he left for Shergadi. It was midnight and pitch dark when he arrived. Mahadev swam across the kitikol. Then, after reaching the royal palace, he entered the bathroom of the Maharaja through a pipe. From there, like a cat, he entered the bedroom of the Maharaja.

Mahdev saw that the Maharaja was sound asleep. He slowly took out the reed and dropped the ants near the Maharaja's feet. These vicious ants spread all over the Maharaja's legs. They made him miserable with their bites. The Maharaja started scratching his legs with both of his hands. He was so uncomfortable that, in his sleep, he took off his trousers and threw them aside. Mahadev was delighted. He quietly picked up the trousers, and, again like a cat, walked out through the pipe through which he had entered.

The next day Mahadev went to the gathering of the thieves with the Maharaja's trousers. When Mahadev arrived, the thieves were impatient to know if he had been successful in obtaining the trousers. Mahadev haltingly opened a bundle, took out the trousers, and placed them on a co:ki: with a smile. On seeing this, all the thieves stood up clapping their hands and singing the praises of Mahadev bishta. Mahadev was deeply pleased. The thieves again accepted him as their clever leader. There are many other stories about Mahadev bishta which entertain the Kashmiri children.

Habba Khatoon

by Braj B. Kachru

Lal Ded contributed the vaks of devotion and wisdom to the Kashmiri language. Habba Khatun, on the other hand, sang songs of love and romance.

Habba Khatun was born in the village of Chandrahar in the sixteenth century. In her earlier days, she was called Zoon (the Moon). She grew up in the midst of the saffron fields and in the shade of the chinar trees. She was not raised as a typical peasant girl. She had learnt how to read and write from the village moulvi. At an early age her father married her to a peasant boy. But this illiterate peasant boy could not keep Zoon happy. He could not understand the longings of her heart. Just like Lal Ded, Zoon also was sad. Lalla became desperate and left her home. Zoon divorced her husband and started singing songs in Kashmiri.

Zoon used to sing in the shade of a chinar tree. One day Yusuph Shah Chak was out hunting that way on horseback. He happened to pass the place where Zoon was singing under the chinar tree. He heard her melancholic melodies, and went to look at her. He was stunned by her beauty. As soon as their eyes met, they fell in love. Later, Zoon and Yusuph Shah were married. She changed her name and became Habba Khatun.

Zoon used to sing in the shade of a chinar tree. One day Yusuph Shah Chak was out hunting that way on horseback. He happened to pass the place where Zoon was singing under the chinar tree. He heard her melancholic melodies, and went to look at her. He was stunned by her beauty. As soon as their eyes met, they fell in love. Later, Zoon and Yusuph Shah were married. She changed her name and became Habba Khatun.

Habba Khatun introduced lol to Kashmiri poetry, lol is more or less equivalent to the English 'lyric'. It conveys one brief thought. It is full of melody and love.

Habba Khatun kept Yusuph Shah under her control. The couple was very contented, and Yusuph Shah became the ruler of Kashmir.

Their happiness did not last long. Akbar came into prominence in Delhi, and he called Yusuph Shah there. In 1579, Yusuph Shah was compelled to go to Delhi. In Delhi, Akbar arrested him. He was kept in prison in Bihar. Poor Habba Khatun was separated from Yusuph Shah. The songs of Habba Khatun are full of the sorrow of separation. It is claimed that Habba Khatun introduced the 1ol into tho Kashmiri (language) After her came Arnimal who also sang mournful lyrics.

A Song by Habba Khatun

Which rival of mine has lured you away from me?

Why are you cross with me?

Forget the anger and the sulkiness,

You are my only love,

Why are you cross with me?

My garden has blossomed into colorful flowers,

Why are you away from me?

My love, my only love, I think only of you,

Why are you cross with me?

I kept my doors open half the night,

Come and enter my door, my jewel,

Why have you forsaken the path to my house?

Why are you cross with me?

I swear, my love, I am waiting for you,

dressed in colorful robes,

My youth is in full bloom now,

Why are you cross with me?

Oh, marksman, my bosom is open

To the darts you throw at me.

These darts are piercing me,

Why are you cross with me?

I have been wasting away like snow in summer heat.

my youth is in its bloom.

This is your garden, come and enjoy it.

Why are you cross with me?

I have sought you over hills and dales,

I have sought you from dawn till dusk,

I have cooked dainty dishes for you.

I do all this in vain!

Why are you cross with me?

I shed incessant tears for you,

I am pining for you,

What is my fault, O, my love?

Why don't you seek me out?

Why are you cross with me?

The shock of your desertion has come as a blow to me,

O cruel one, I continue to nurse the pain.

Why are you cross with me?

I have not complained even to the spring breeze

That is my agony.

Why have you forgotten me?

Who will take care of me?

Why are you cross with me?

I swear by you

I do not go out at all,

I don't even show up at the spring.

My body is burning,

Why don't you soothe it?

Why are you cross with me?

My hurt is marrow deep; I did not complain.

I just wasted away for you.

I have suppressed endless longing,

Why are you cross with me?

I, Habba Khatun, am grieving now.

Why didn't I ever greet you, my love?

The day is fading and I keep recalling,

Why are you cross with me?

Ghulam Ahmad Mahjoor

by Braj B. Kachru

Mahjoor has a place of honor among the poets of Kashmir. He is especially noted for two things. First, he introduced a new style into Kashmiri poetry. Second, he introduced a new thought into Kashmiri poetry.

two things. First, he introduced a new style into Kashmiri poetry. Second, he introduced a new thought into Kashmiri poetry.

Mahjoor wrote poems of freedom and progress in Kashmiri. These songs awakened the sleeping Kashmiris. He came with a new voice and a new (literary) form.

Mahjoor was a poet of love and communal harmony. In his earlier days, he used to write only love poetry, but (later) he also wrote forceful poems about freedom.

Mahjoor's real name was Ghulam Ahmad. But as a poet, he adopted the pen name 'Mahjoor'. He was born in eighteen hundred and eighty-five in Metragam. He has written poetry in Persian and Urdu as well.

Mahjoor worked as a patwa:ri: (pathva:r') in Kashmir. Along with his official duties, he used to write poetry in Kashmiri. Mahjoor had his first Kashmiri poem published in 1918. After this, he composed poetry only in Kashmiri. His songs became very popular. He wrote on such topics as love, communal harmony, and social reform, and also wrote on the plight of the Kashmiris. He wrote about youth, the flowers of Nishat Garden, a peasant girl, a gardener, the golden oriole, and a Free Kashmir. At that time, such songs were unknown in Kashmiri poetry. It was Mahjoor who gave these to us.

Mahjoor was sixty-seven years old when he passed away in 1952. The death of Mahjoor was a great loss to both the Kashmiri language and (Kashmiri) poetry. But, Mahjoor's songs are still on the lips of every Kashmiri. Through these songs, his name will live forever.

Come, O Gardener

by Gulam Ahmad Mehjoor

Come, O Gardener!

Come to create the glory of a new spring.

A spring in which

the gul will bloom,

the bulbul will sing.

The garden is desolate;

the dew is mourning.

And the gul in torn robes

looks perplexed.

Come, O Gardener!

To rekindle the gul

To rejuvenate the bulbul.

Come, O Gardener!

Weed out the nettle from the flower-beds

And look at row after row of hyacinth,

Come and make a smiling garden.

Who can free a captive bird mourning in his cage?

You must bring your own freedom, O, Gardner!

Wake up, O Gardener, to realize that

power and riches.

Comfort and kingship,

all these are at your feet

only after you realize yourself;

O Gardener!

Come, O Gardener!

to awaken your garden,

to say goodbye to the strains of gul,

to say goodbye to the strains of bulbul;

And--

bring about an earthquake,

bring about a storm,

bring about a rumbling thunder,

bring about a tornado.

Dina Nath Nadim (1916-1988)

by Braj B. Kachru

Department of Linguistics, University of Illinois

Urbana, Illinois 61801 U.S.A.

Reproduced from:

Naad, All India Kashmiri Samaj

Dina Nath Nadim (1916-1988): Epoch-maker and trend-setter in Kashmiri poetry and prose, Dina Nath Kaul Nadim was born in March, 1916 and passed away on April 8, 1988. We cherish his memory and as a token of our respectful homage to this great literatuer and a lovable human being, we reproduce here this article authored by Prof. Braj B Kachru, an America based linguist/scholar.

and prose, Dina Nath Kaul Nadim was born in March, 1916 and passed away on April 8, 1988. We cherish his memory and as a token of our respectful homage to this great literatuer and a lovable human being, we reproduce here this article authored by Prof. Braj B Kachru, an America based linguist/scholar.

This article had appeared in the quarterly journal Kasmir (August, 1988) published from Ontario, Canada. It was made available to us by Shri M L KAUL, the former Gne. Secy and present Vice President of AIKS, for which NAAD is thankful. - Editor

The Renaissance of Kashmiri literature as of several other Indian literatures, is closely linked with post-independence literary activities. The political events in Kashmir, especially the 1947 attack, resulted in the mobilization of Kashmiri writers and other artists in defense of their valley. The first onslaught came around October 22, 1947. In response, the Cultural Front was hastily organized. For the first time artists were assigned a role in a period of turmoil and aggression. The Cultural Front had three units for writers, actors and painters. These units played an impressive and unprecedented role in keeping up public morale by taking the message of secularism, communal harmony and patriotism to the people in their own language in both rural and urban areas.

The establishment of Radio Kashmir on July 31, 1948, provided a daily forum and great opportunity for the use and development of Kashmiri language. Radio Kashmir used Kashmiri - until then generally called a "vernacular" - in a variety of new contexts. The implication of the new roles for the language was that creative writers seriously attempted those literary forms which had been neglected earlier, for example drama, short stories and discursive prose. Until this time the main literary form was poetry and the dominant themes were nationalism (defined rather narrowly), Kashmiri identity, and religious harmony, In 1958, the Jammu and Kashmir Academy for Art, Culture and Languages was founded; it provided further encouragement.

It was during this unexpected political turmoil in the otherwise calm valley that Dina Nath Nadim (b. 1916) came into the limelight. He has remained in the forefront of the Kashmiri literary scene ever since.

In the not-so-uncommon Indian tradition Nadim's mother had a significant influence on his growth as a poet, especially after his father Pandit Shankar Kaul died when Nadim was only eight years old. Nadim's widowed mother would sing the Vaks of Lalla and would recite Lilas of other poets and an occasional composition of her own to the boy and his sister. Her repertoire of Kashmiri poems was large since she originally came from a village Muran where the oral tradition of poetry was part of the culture. Nadim was educated in local schools with intermittent breaks. He matriculated in 1930, received his B.A. in 1943, and earned a Bachelor of Education degree in 1947.

There is no published collection of Nadim's work; indeed, he is somewhat indifferent about assembling one. (SHIHIL KUL - a collection of Nadim's poems has been published since, for which the poet was honoured with Sahitya Akaddemy Award-Ed.). Most of his poems were either presented in poetic symposia (musha'ira or kavi sammelan) or published in local journals. The total number of his poems is around one hundred and fifty including those in English, Hindi, and Urdu. Like his predecessors and some contemporaries, his decision to write in Kashmiri was a late one. Nadim's poetic career did not really start until late 1930's; before that he had composed some poems in English. Between 1938 and 1946, he wrote mainly in Urdu - and some poems in Hindi - under the influences of the Kashmiri Pandit poet Brij Narain Chakbast, Josh Malihabadi and Ehsan bin-Danish. This was essentially a period of apprenticeship under the ideological influences of Hinduism, Sufis and Khayyam. Nadim was trying to discover himself and his linguistic medium. He finally selected Kashmiri for, as he has said, "my mother tongue has greater claim on me."

This realization resulted in Nadim's almost exclusive concentration on Kashmiri. He had written his first Kashmiri poem in 1942 on "Maj Kasir" ("Mother Kashmir"), an appropriate topic for a time when Kashmir was passing through a critical phase with the mass movement slogan "Quit Kashmir" challenging the established Dogra dynasty. A handful of Kashmiri writers were expressing political sentiments ornately embroidered with gul-o-bulbul imagery, but Nadim did not become fully part of the movement until 1946. It was then in a musha'ira (poetic symposium) organized by a fellow poet, Arif, that Nadim read the poem Sonth ("The Spring").Then followed Aravali Prarakhna and Grav ("A Complaint"): poems of patriotism, revolution and freedom. Here he is asking the kinds of questions which members of the progressive writers movement were already asking in other parts of India. Consider, for example

Why should the share of a labourer be

stolen by a capitalist?

Why should a honey-bee circle the

flowers and take away their honey?

This theme was not new for Indian poetry but it was new for Kashmiri.

The next phase came suddenly and unexpectedly in 1947 and 1948, when Maharaja Hari Singh left the state destitute at the time of Pakistan instigated invasion. This attack mobilized the Kashmiris, and writers and artists organized themselves under what was called the National Cultural Front.

Nadim was in the vanguard of the group. A withdrawn and soft- spoken figure, he was the life of mushairas and rallies, reading poetry of protest, revolution, and reassessment. These themes demanded new poetic forms and an extension of the earlier stylistic range of Kashmiri.

The borders of the state had turned into battle fields; the poets turned to patriotism, and poetry was used as an awakening call to Kashmir's youth. Here Nadim was again in the forefront. Even the titles of some of his poems are suggestive of turmoil of the period, for example, Tsi Mir-i Karavan ban ("You Become the Leader of the Caravan"), Naray Inqalab ("The Call for Revolution"), Me Chu H'ond ti Misalman beyi Insan Banavun ("I have to turn Hindus and Muslims into human beings again"), Servani Sund Khab ("The Dream of Sherwani"), and Pritshun Chum ("I Must Ask"). Although a translation cannot convey the flow and force of the original, the message of this period was

Burn and burn like the colourful field

of lalizar !

Roar and roar like a watertall !

You are fire

A furious fire of burning youth.

Come out

And cross the hills and dales

Raise a storm !

Contrast this with the melodious folk style which has a carefree lilt as it expresses underlying discontent:

Ya Sah-i Hamdan !

Ya Sah-i Hamdan !

Are we human?

Who says human?

The winter is ahead of us

The pocket is penniless

The hovel is roofless;

And the law is chasing us

Do you care?

I don't care !

Ya Sah-i Hamdan !

Ya Sah-i Hamdan !

The experimentation and searching continued, both for suitable poetic forms and for an ideology. Like many of his contemporaries, Nadim also joined the Communist Party. His elder contemporary Mahjur had already become a "fellow traveller.''

In 1950 Nadim provided a contrast with the traditional Kashmiri poetic forms by introducing blank verse in Bi G'avi ni Az ("I Will Not Sing Today"). This new poetic form caught the imagination of Kashmiris - literate and illiterate. Other poets, considering it an emancipation from rigid formal poetic constraints, soon followed this style. Rahaman Rahi's G'avun Chum ("I Have to Sing") clearly shows Nadim's influence. Not only did Bi G'avi ni Az demonstrate that blank verse could be used as an effective poetic form in Kashmiri, but in that poem he also showed his subtle feeling for an appropriate lexical choice, and for the proper blend of sound and sense. This effect is created neither by Persianization nor by Sanskritization; rather, he firmly established the process of Kashmirization:

Bi g'avi ni az

ti k'azi az chi jangbaz jalsaz

hol gandith

Kasiri m'ani zag h'ath.

Nadim included Jungbaz and Jalsaz because these words have been nativized and are an integral part of Kashmiri vocabulary. He chooses native collocations and embeds them in new contexts, e.g., holgandith, zagh'ath, ayigrayi. But it was the musical lilt of the poem which made it irresistible to Kashmiris; never before had their language been used with such alliteration and lexical dexterity:

bi g'avi ni az su nagmi kanh

ti k'azi az - ti k'azi az

be vayi jayi jayi tapi krayi zan

b'ehi zag h'ath

karan chi ayi grayi yuth tsalan

yi m'on bag h'ath...I will not sing today,

I will not sing

of roses and of bulbuls

of irises and hyacinths

I will not sing

Those drunken and ravishing

Dulcet and sleepy-eyed songs.

No more such songs for me !

I will not sing those songs today.

Dust clouds of war have robbed the

iris of her hue,

The bulbul lies silenced by the

thunderous roar of guns,

Chains are all a-jingle in the

haunts of hyacinths.

A haze has blinded lightning's eyes,

Hill and mountain lie crouched in fear,

And black death

Holds all cloud tops in its embrace,

I will not sing today

For the wily warmonger with loins girt

Lies in ambush for my land.

Another stylistic innovation, in the form of the dramatic monologue, came in Trivanzah ("Fifty-three"). These innovations excited the younger writers; slowly Nadim's spell spread, and the Nadim Era was born. Nadim's political activism continued during this period. He was active in defence of world peace, and was elected the General Secretary of the State Peace Council (1950). He participated in the Indian Peace Conferences of 1951 and 1952. His pacifism is based on his "hope of tomorrow,'' which he expresses in Me Cham Ash Paghic ("My Hope of Tomorrow:):

I dream of tomorrow

When the world will be beautiful !

O how bright the day, how green

the grass !

Flowers paradisal, earth aching

with joy,

And dancing tountains of love

in his breast !

The world will be beautitul !

A rare confluence of happy stars !

wim my eyes sparkling wimout

collyrium.

Rose-red nipples, breasts swelling

with milk

The world will be beautiful !

His peace is not abstract and incomprehensible. Rather, it is related to day-to-day emotions, the return of "my love" for whom

When me soft dark comes, I'll be a

Heemaal

Bursting with love, waiting behind the

shrubs.

He will be late, but I will be Patience.

I have a rendezvous!

And

They say war is breaking out,

But surely not tomorrow

When my husband is coming!

It can't break out tomorrow!

While these are "political" poems with a socialist background, the themes have been personalized. The result is that, even as "political pieces,'' they do not sound like slogan mongering.

Another poem of this period, Dal Hanzni Hund Vatsun ("The Song of The Boatwoman from the Lake Dar'), displays exquisite sensitivity in the selection of typically Kashmiri diction and awareness of appropriate style shifts. In Kashmiri poetry Gris' Kur ("The Peasant Girl") had been seen earlier as a personification of Himaal of Heaven or a "Caucasian Fairy," to whom flowers would whisper and bulbuls would sing. But now, for the first time, a Kashmiri boatwoman becomes an object of an intense poem. A dal hanzan' selling vegetables is as much a part of Kashmir as is the Sankaracharya temple of Srinagar; but a haazan had never been viewed with such pathos before, and with such close analysis of emotions. Nadim re-created the reality which had previously escaped the poets' eye.

I

I got these Crisp and fresh from

the Dal

Hay valay, come and buy! hay valay,

come and buy!

These are tiny eggplants, and these

are round gourds.

Hay valay, come and buy !

Hay valay, come and buy !II

These are peppers, and these are

brinjals.

The brinjals are like pitchers of wine

banging their heads in this boat of

mine,

Hay valay, come and buy !

Hay valay, come and buy !III

The crisp bundles of radishes

are glittering in the shade

of weeds, the red marsh turnip

is blushing like a blushing beauty,

as it the dawn has blossomed into

flowers.

Hay valay, come and buy !

hay valay, come and buy !IV

May dust fall on you! Stop it !

You have taken enough now.

I know, dear lady, I cannot blame you,

tor the high prices are crushing us all

now.

Let me go!

Come on, lend me a hand with this

basket, I really must go now.

Hay valay, come and buy !

Hay valay, come and buy !V

What can I tell you, dear lady.

My child was born only last Thursday,

Though I didn't feel up to it, I dragged

myself out and left my little one behind.

It was paintul to leave him away

from me.

Hay valay, come and buy !

Hay valay, come and buy !VI

My little one !

My little one is pale like a radish,

My little one is pale like a jasmine,

My little one is naked and nude

shivering and cold like a lump of ice.

My little one is crying and crying, the

tears roll down from his eyes like drops

rolling down from lotus leaves.

Hay valay, come and buy !

Hay valay, come and buy !VII

My little one's nose is like a lotus seed,

just like his father's nose;

My little one's face is tiny, just like

his mother's face.

To us both he is like a lotus, sprung

from the mud of dalay hay

Hay valay, come and buy !

Hay valay, come and buy !VIII

Lo ! I seem to hear a baby cry;

Lo ! I seem to feel a sensation in my

breast.

My heart doesn't seem to be here now.

Dear lady, I must really go now,

Hay valay, come and buy !

Hay valay, come and buy !

In 1953 Nadim's experimentation took a different from; he wrote the first opera in Kashmiri, Bombur ti Yambirzal ("The Bumblebee and the Narcissus"). The theme depicted the ultimate triumph of good over evil. The interpretations of this opera were appropriate to the time: "exposing and defeating the conspiracies of Storm and Autumn against the Narcissus and the Bumble-Bee, who with their fellow-flowers symbolize the people and their aspirations for a spring and its joys". This opera was an instant success. But Nadim's experimentation with poetry continued; in Lakhei Chu Lakhcun ("Lakei Has a Mole"), for example.

There was a period of four years during which Nadim composed sonnets following both the Petrarchan and Shakespearean conventions. In them we again find selective diction, suggestive imagery, and delicate linguistic craftsmanship. Consider for example, this translation of Zun Khats Tsot Hish ("The Moon Rose Like a Tsot'):

That day, the tsot-like moon ascended

behind the hills looking

wane and worn like a gown of Pampur

tweed

with a tattered collar and loose collar-

bands,

revealing sad scars over her silvery

skin,

She was weary and tired and

lusterless

as a counterfeit pallid

rupee-coin

deceittully given to an

unsuspecting woman labourer

by a wily master.

The tsot-like moon ascended and the

hills grew hungry.

The clouds were slowly putting out

their cooking tires.

But the forest nymphs began to kindle

their oven tires.

And steaming rice seemed to shoot up

Over the hill tops.

And, murmuring hope to my

starving belly.

I gazed and gazed at the promising

sky.

In the 1960s, after trying new forms such as free verse, the sonnet, etc., Nadim came back to the native folk tradition, and the well-established Vak form which had reached its culmination in Lalla. In recent years Nadim has been experimenting with poetic compositions which he terms zit'nl ("fireflies"). In this new form he is following the Japanese haiku style, comprising seventeen syllables in three lines with 5, 7 and 5 syllables each. The Japanese originally used the haiku for objective descriptions of nature or of the seasons; it was intended to evoke an unstated but definite emotional response. Later its range was extended, but brevity and suggestiveness remained its main marks. In Zalir'Zal ("The Cobwebs") Nadim introduces pointillism or neo- impressionism. In some sense this is also present in zu'nt composition. Nadim's dexterity in stylistic innovation and the freshness of his themes helped him to steal "a march over the predecessors and contemporaries." His technique is simple: he seems lo use words rather as clever children use marbles with intriguing combinations and creative effects in a seemingly effortless display of craftsmanship. One is left wondering, why could not I think of that". Not many of Nadim's contemporaries could think of comparable devices, which explains why as his contemporary Lone says, they "were not only influenced by Nadim, but also inspired to write in his vein. Some of them went to the extent of copying his style while some adopted his themes in their poems."

The secret of Nadim's art seems to lie in his intuition for an effortless use of a limited but highly appropriate vocabulary, a keen ear for the sound and rhythm of his native language, and, above all, an artist's instinct for combining all his formal apparatus in fresh imagery. For example, in Iradi ("Determination"). Nadim handles an old theme with new lexical cohesion and effect. Iradi certainly is not his best poem; indeed, it may even be called a propaganda piece. But even in this poem one marks extremely effective lexical alteration, re-duplication, and alliteration. It is his use of such devices which separates Iradi from poems written on such patriotic themes by other Kashmiri poets.

This craftsmanship is more fully displayed in poems such as Lakhei Chu Lakhcun ("Lakhei Has a Mole"). Nabad ti T'athvani ("Rock Candy and Worm-seed"). In Iradi, the key lexical items seem to be vozul (red) and vusun (warm). Around these two words Nadim develops lexical sets of nouns and verbs, choosing members for each class with his eye on the total semantic effect. Nouns convey movement, turmoil and commotion; verbs connote sacrifice and martyrdom (e.g., fida gatshun, jan d'un, dazun). Consider, for example, the nouns avlun, jamun, jos, malakh, nar, tufan, vav, and vuzimali. Nature seems to be a party to this outward commotion and inward determination with veezimali (thunder) providing signs and bun'ul (earthquake) indicating restlessness. Reduplication further enhances this effect (e.g., vusunvisun, vozulvozul, yi avlun, yi avlun, tavay tavay). We have already seen suggestive imagery, a typical Nadimian device, in Zun Khats Tsot Hish.

Nadim has passed through many stages, and at each stage he has engaged in distinct thematic and stylistic experiments. That process still continues; so does the Nadim Era.

Kashmiri Sama:va:r

There is no home in Kashmir that does not have a samovar. Each family has one or two samovars. Kashmiris make tea in the samovar. Kashmiris are very fond of tea. That is why any time is considered tea time.

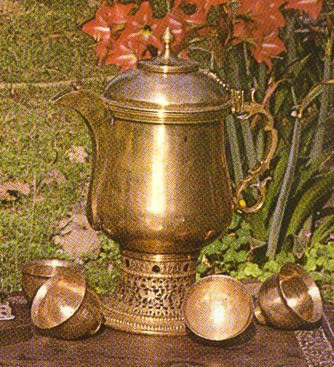

Koshur Sama:va:r with 4 khae:s (cups)

Inside a samovar there is a fire-container in which charcoal and live coals are placed. Around the fire-container there is a space for water to boil. Tea leaves, sugar, cardamom, and cinnamon are put in the water.

Samovars are not of only one type. Some samovars, in which only one or two cups of tea can be made, are very small. Other samovars, in which hundreds of cups of tea can be made, are very big. Samovars are made of copper or brass.

Kashmiris can make two or three types of tea in the samovar. The kehvi is the favorite tea of Kashmiris. This tea is also call mogil cha:y. There is a special tea for making it. It is called bambay cha:y. The bambay cha:y, sugar, cardamom, cinnamon, and almonds are boiled in water, but no milk is added.

The second type of tea is dabal cha:y. It is made with bambay cha:y, sugar, cardamom, and almonds. Milk, however, is also added. Kashmiri Pandits serve dabal cha:y at weddings and on feasts.

The third type or tea is called shi:r' cha:y. This type is not made with bambay cha:y. There is another kind of tea used for making that. It is prepared with bicarbonate of soda, salt, milk, and cream (mala:y). It has a very pleasant color. Shi:r' cha:y also is a typically Kashmiri tea, but not everyone likes it.

Tea being poured from a sama:va:r into a kho:s (cup).

A kangir, the traditional Kashmiri fire-pot, is nearby.

Recently, some Kashmiris have started drinking Lipton tea. But even now, the favorite tea of Kashmiris is kahvi. It is said that good kanvi cannot be made without the samovar.

It is difficult to say when the samovar was first introduced into Kashmir. In addition to Kashmir, the samovar is also found in Russia and Persia. Kashmiri tea can only be enjoyed in a Kashmiri kho:s (cup).