|

Originals |

Replacements |

| amipana | Oma pana |

| Jin | ya zi |

| bhava ruja | bhava raj |

| vachun | vakhchun |

| nangai | nihangai |

| divar vata | dehvar vata |

| pyatha buan | shuniya and earth |

| hoota bata | huta ba hatha |

| al, pal, vakhur | gar kee samgree (Hindi Translation) |

| kan | kad |

| vanun | woni na yun |

| kol and akol | vakhat, be-vakhat (Hindi Translation) |

| vakh, manas | mansik japa (Hindi Translation) |

| asi | a-oose |

| samahan | samtahan |

| vokshun | voha-akhyun |

| kahan | kohan |

| abakh chyan | abodi chyan |

| razdane | rasdwaney |

| tirath ros | titha rasi |

| mali | moal |

| zanha | zan yee ha |

| kruth | kiva ishto (Hindi Translation) |

| paran (read) | paran (decorate) |

| zaldava | zaldyon |

| mot-bolnovum | mann bodhi novum |

| milith tas mann | milvith mann pran |

| dama dama kormas | damaha dommus |

| gati | guthi |

| chentan dih vankavan | chenta dehas vyan kyah von |

| anta | anti |

| yorai ayi | yava rayi ayi |

| turi | turiya |

| nata and kyah | huta and kyat |

| loosas | lah achus |

| althan | aalithan |

| bara bara | bari bore |

| loosum | losi |

| suman swathe | sum na swathe |

| bhan | ba van |

| chandar | cha ondur |

| agrai | agar ai |

| sadai | sadiva |

| bata | yuth haba hatha |

| dharti | darith |

| srazak | satraz aakh |

| nom | nav |

| yihai | shivai |

| kruth | kiva ishto |

| thali-thali | a - utyam thali |

| luka gari | loktyan garan |

| gur | gor |

| palnas | palnas |

| ashvawar | ath savar |

| kha-swaroop | ksha and h swaroop |

| chandrai | cha-andrai |

| garan | gwaran (Arabic) |

| aham | ham |

| chyath | swapnya |

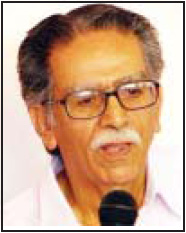

Prof. M.L. Koul

With a brilliant academic record which includes three post-graduate degrees in English, Hindi, Sanskrit and B.Ed. from the University of Kashmir, Prof. Mohan Lal Koul served various academic colleges of Jammu & Kashmir State. As a student he was affiliated with the left -wing politics and zealously participated in cultural activities organised under the aegis of various cultural fora. He taught Kashmir Shaivism at Benars Hindu University as a visiting professor under U.G.C scheme. He also acted as an advisor of DAV Institutions in Delhi.

Apart from contributing articles to papers and journals on subjects related to history, culture, aesthetics and philosophy, Prof. Koul has authored a book on Kashmir crisis titled as "Kashmir-Past and Present, Unravelling the Mystique", which has been broadly appreciated for the documentation of facts and features about the fundamentalist developments in Kashmir.

In his brilliant foreword to the book Shri T.N. Chaturvedi, a scholar- politician, has put, "Shri Koul deserves all commendation for writing a book which helps to illumine many dark corners. It is a scholarly and documented work without being ponderous. It is a authentic in its composition and unsparing in its presentation of even unpalatable facts."

His writings have served to de-mythologise Kashmir's medieval and modern history.

Tributes

Pt. Hargopal Koul - The Lion Of Kashmir

By Prof. M.L. Koul

The multi-faceted personality, Pandit Hargopal Koul Khasta, popularly known as the lion of Kashmir, was an ardent patriot and a dominating intellectual of his times. The ancestors of his illustrious family had migrated to the Punjab, probably in search of livelihood, in the Sikh times. In one of his works he makes a mention of the migration of his ancestors to the Punjab, but does not divulge of fuller details about the motivating causes of their voluntary migration. His young brother, Salig Ram Koul Salik, writes about his family having lived in Punjab for three generations. As per the details available from Pandit Hargopal Koul and his brother, Salig Ram Koul, it can be safely established that Pandit Gasha Koul was their great grand-father and Pandit Ram Chand Koul was their grand father. Both of them had scholarly bent of mind and Kashmir Shaivism was their forte. The maternal grand-father of Pandit Hargopal Koul was Pandit Ved Ram Mattoo, a grandee (rais) in the cruel times of Afghans. As he belonged to an illustrious family, Pandit Hargopal Koul instinctively perpetuated the rich family tradition through his forays into the domains of poetry, history, politics, journalism, education and social reform. In Kashmir he is better known as an untiring crusader who highlighted and fought for the social and political causes that had lot many ramifications for transforming the over-all complexion of Kashmiri society as a whole. He was gutsy and faced once the wrath of Maharaja Ranbir Singh with exemplary courage and aplomb. He did not dither but set the Maharaja thinking through his bold responses to the false, and acrimonious accusations that were coined by the conspiring elements in the court.

The ancestors of Pandit Hargopal had some chunks of land at Reyiteng in Rainawari, Srinagar but because of its unproductivity they could not, wholly depend on it as a safe source of sustenance and had thought of migration in search of a living. Most of his ancestors were in the British service. Pandit Kailash Nath Koul, who was his uncle was an employee of the Settlement Department in Ludhiana. While in the Punjab, Pandit Hargopal Koul had joined a school as a teacher. It is buttressed by the hint, that he throws in the introduction to his work, Gulzari-Fawayid'. In his work 'The History of Kashmiri Pandits', Pandit Jia Lal Koul Kilam writes that Pandit Hargopal Koul was in the British service and was entrusted with some jobs political in nature. That he was in such service is supported by Pandit Hargopal's own statement about his transfer to Shimla from Patiala. As a teacher in Lahore he had established contacts with many Englishmen and Indian scholars responsible for shaping the political and literary ethos of the Punjab. The'Guldasta-i- Kashmir' makes a mention of his having sent the book to Col. Halride for his study and comments.

Being thoughtful and intellectually vibrant Pandit Hargopal Koul could not escape the impact of western ideas that were fast impacting the politics, education and thinking patterns of the natives. Lured back to Kashmir by the good times that were ushered in by Maharaja Ranbir Singh Pandit Hargopal Koul pioneered a plethora of political, social and educational activities that are a clinching witness to his renaissance spirit of revival and transformation. He zealously made concerted efforts to put the Kashmiri life-pattern on new rails of change, reform and revival for a new orientation and intellectual awakening. The western ideas that he had imbibed during his stay in thePunjab made him an ardent votary of change but he spurned the type of change that would erode the fundamental identity of the natives as one bonded ethnic group. Renaissance, to him, meant change based on reform and purging of pernicious social evils, yet he was in no-way for the uprootment and dislocation of his people from their historically and culturally evolved mould and ethos.

While in the Punjab Pandit Hargopal Koul had rubbed shoulders with the prominent leaders of Arya Samaj who had spearheaded a powerful campaign against the evils that had crept into the Hindu society. As an intellectual of great calibre he totally rejected the tinsel tampering that the Arya Samajists had indulged in with some of the august beliefs and doctrines of the Hindus. He was for widow-remarriage but bitterly opposed the Arya Samaj campaign against idol-worship. His long association with Arya Samaj in the Punjab was highly prized by its leaders for the terrific oratory that he harnessed to expand the mass base for the reform movement launched by Arya Samaj. In Kashmir his campaign for widow-remarriage was lost on deaf ears as Kashmiri Pandits, though progressive in mind and outlook, detested it. But Pandit Hargopal Koul continued with the campaign and never relented. He was both tenacious and audacious in the pursuit of a cause for social and political upliftment of his people and no opposition, weak or strong could deter and thwart him-in his tracks.

As an active participant in the educational and reform movements of the Punjab, Pandit Hargopal Koul had developed and cultivated thick contacts not only with some Hindu leaders, but also with a few influential Englishmen having an aptitude for education and research. Though conscious of the British ascendancy in India, yet he detested the role of the Christian missionaries artfully engaged in the conversionary campaigns in the Punjab and elsewhere. He was a part and parcel of the Arya Samaj movement in its opposition to the Christian missionaries and its positive role in strengthening the Hindu society purged of its corroding fault-lines. His intellectual approach to the complex problem of reform in Hindu society was to cement, when shorn of its evils for progress and advancement on modern lines as blazed by the Britishers. A Hindu society freed from debilitating evil customs would automatically detest and fight back the missionaries out to convert its members through state patronage and lure of money.

As he had strong affinities with Arya Samaj, he had studied Satyartha-Prakash - a major work that had dealt with the doctrinal positions of Islam and Christianity. His stay in the Punjab had brought him face to face with the Muslim communalism which ultimately led to the partition of India based on two-nation theory. Though a thorough liberal in his world-view, Pandit Hargopal Koul Khasta found himself in a piquant situation when a mullah, who had trespassed into his privacy, cried foul of heresy when he was vigorously asked to remove the trespass. The mullah was beaten and his room ransacked for his defiant attitude. With a view to garnering support from his co-religionists the mullah accused him of insulting the holy book which as per him he was teaching to a few students in the room. There were noisy demonstrations against this alleged act of Pandit Hargopal Koul. The government of Ranbir Singh detained him and instituted a criminal case against him. As a person of inexplicable guts and valour Pandit Hargopal Koul faced the situation with cool and calm mind. The charge as levelled against him by the mullah could not be upheld by the court and Pandit Hargopal was honourably released. But the ruler externed him from Kashmir ostensibly to maintain public peace.

Pandit Hargopal Koul was the last man to compromise with Muslim Communalism. He was no Prem Nath Bazaz who pandered Muslim communalism and offered dubious and devious explanations for the loot of Kashmiri Pandits in 1931. Pandit Hargopal Koul through one of his curt and straight retorts to a mob reminded it of the petition that Muslims had made to the Maharaja for granting them entry into their original religion. It is said that the mob appreciated his frank audacity to tell the truth to its face and quietly withdrew from the scene. His trial in a court of Srinagar attracted lots of angry crowds and Pandit Hargopal's bold defiance is too well-known to be reiterated.

The much publicized mullah-episode involving Pandit Hargopal Koul followed the serious involvement that he had in the petition that some mischievous people had made to the British government in the wake of a terrible famine that ravaged Kashmir in 1876 A.D. As a dominant and unique personality of his times Pandit Hargopal Koul had won kudos and detraction from those who highly appreciated his role in the polity and those who detested him for all what he did. Kashmir as always has been a notorious breeding ground of rumours and people being strangely sentimental, for historical reasons, are immediately swayed by them. As the famine took its heavy toll a rumour was mischievously set afloat that Maharaja Ranbir Singh carried boatfuls of Muslims and drowned them into the choppy waters of Wullar lake. The British Government instituted an enquiry into the allegation. The British officer asked the Pandit to present himself before the enquiry officer. Alarmed in the least by the developments Pandit Hargopal Koul did go to the Durbar and audaciously asked the Britisher who the prosecutor was and who was the judge. The officer said that it was 'sircar'. Pandit Hargopal Koul flared up and fearlessly said that it was inconceivably strange justice where the prosecutor and the judge were the same person. The Maharaja on the throne lost his royal cool and was about to pounce on the Pandit when Wazir Punnu stopped him in his tracks. The Maharaja, though responsible for a new renaissance in Kashmir, failed to comprehend that the British were the source of the mischief and were capitalising on it only to force his climb down on the issue of his non-acceptance of a resident in his court supposed to safe-guard the imperial interests in the state.

The charge against Pandit Hargopal Koul could not be legally proved. Yet the Maharaja ordered his imprisonment. He and his brother Pandit Salig Ram Koul Salik were ordered to be lodged in the Bahu Fort in Jammu. During their incarceration in the fort both the brothers prayed, studied and indulged in acts purporting deliberate defiance of the royal authority. Once they caught hold of the prison officer, who was a close relation of Maharaja Ranbir Singh, and gave him a thrashing. A dogra lady witnessing the scene got convinced of their being courageous and out of regards used to bring them food from her home for the period they were in the prison. One fine morning, there was commotion in the prison and it was found that Salig Ram Koul had disappeared from the prison. On thorough inspection the authorities shockingly discovered that he had dug a tunnel in his cell through which he had made good his escape to an unknown destination. Pandit Hargopal Koul vociferously accused the Maharaja of getting his younger brother brutally killed with impunity. The Maharaja launched an enquiry and informed Pandit Hargopal that his brother had fled to Patiala where he had started a paper to denounce him and his ways of governance.

Pandit Hargopal Koul as the prominent leader of Kashmir heralded a movement that clamorously opposed the monopoly of the Punjabis and Bengalis in the state services. The Maharaja pursued a policy which ignored the interests of indigenous Kashmiris and imported officers from outside the state. The Kashmiri Pandits having opted for modern education with English as the medium of instruction were in the vanguard of the movement. Both Pandit Hargopal Koul and Pandit Salig Ram koul ably highlighted the demands of mulkis (locals) and established contacts with the people of Jammu, thus giving the movement a new pace and acceleration. Maharaja Partap Singh was quick enough to recognise merit of the demand through the concerted efforts of koul brothers. In Maharaja Hari Singh's time the demand gathered a new momentum when a conference on the issue was held at Jammu under the presidentship of Pandit Jia Lal Koul Killam. The movement is also known as State-Subject Movement. It had no political overtones. It was in no way repugnant to any political alignment that the state would forge in view of new political developments in the sub-continent. Pandit Hargopal Koul was an Indian patriot who always saw future of the state as part of a political system guaranteeing personal liberty and equality before law.

Pandit Hargopal Koul had tremendous journalistic calibre and abilities which he had amply demonstrated through his, powerful writings in Punjab. The topics which found elucidation at his hands pertained to social reform, education and current problems. The deft handling and elaboration of moot problems helped him a lot in carving out a niche for himself in political, social and educational circles of the day. His externment at the hands of Maharaja Ranbir Singh, who had great respect for him, was a dominant theme of his writings. He had hate-love relationship with the Maharajas of Kashmir. As per Mohd. Din Fauq Pandit Hargopal Koul issued a weekly 'Khair-KhwahiKashmir' from Lahore which he used as a potent vehicle for bitter criticism of the Maharaja as he had unjusty expelled him from Kashmir to appease Muslims. When in the good books of Maharaja he was placed in-charge off the Publication of the 'Tohfai-Kashmir' and all matters relating to its management. At the recommendation of Dewan Anant Ram he was given the charge of over-seeing all the journalistic activities in the state which he performed so efficiently that Maharaja recognised him as an able intellectual of his state. As part of his official duties Pandit Hargopal would read out to the Maharaja the contents of all the papers issued within the state.

During the years of his externment in Punjab Pandit Hargopal Koul issued a paper 'Ravi-Benazir' and 'Subaha Kashmir' from Amritsar. Later on, through the paper he vigorously crusaded against the Britishers who had deposed Maharaja Partap Singh, shorn him of his powers and installed a regency council with his rivals as its members. The campaign in the press was so vigorous and consistent that the Britishers got exposed for their conspiracy against the Maharaja. Partap Singh could not be kept away from his throne and all the royal powers were restored to him. Pandit Hargopal was allowed to return to his native place and people of all shades accorded him a rousing reception only to justify his sobriquet of 'lion of Kashmir', which at a later date was appropriated by Sheikh Abdullah.

Having the vision and comprehension of an educationist Pandit Hargopal Koul ably pioneered a plethora of educational activities that had marked bearing on the transformative processes of the Kashmiri society stepped in conservatism. Who else but him could visualise the importance of imparting education to a girl child? For this purpose, despite the stiff opposition of the social conservatives of all shades, he founded a girls school under the head-ship of his own daughter, Shrimati Padmavati, a legendary figure in the educational history of Kashmir. The school flourished beyond expectations and attracted girls from all classes of people. A chain of seven such schools was opened in the different localities of Srinagar to serve the enslaved girls only to usher them into a new era of glittering enlightmenment. The government of the day did not fail to duly recognise the educational importance of girls' schools and formed a committee for their effective upkeep and management with Pandit Hargopal Koul as the President.

A veritable pioneer in the field of modern education in Kashmir, Pandit Hargopal Koul founded a Hindu school for boys as well. Over the years the school was upgraded and christened as Sri Partap College which has played a brilliant and commendable role as a centre of academics in giving a new fillip to modern education in Kashmir. It is pertinent to put that his younger brother, Salig Ram Koul Salik, equally a genius, was also involved in all such pioneering activities in the domain of education in Kashmir. Both of them in complete unison founded some arts and crafts schools where vocational training was imparted to the entrants. Some new-type Anglo-vernacular schools were started which combined the teaching of local languages alongwith English alphabets only to prepare scholars for a better future.

Pandit Hargopal Koul was a scholarly historian in his own right. His much acclaimed work on history titled as 'Guldasta-i-Kashmir' establishes him as a historian of genuine credentials. His awareness of the tools of history enabled him to go to the sources of Kashmir history and geography. For his initiation in Rajtarangini as the magnum opus of Kashmir history, Pandit Hargopal Koul sought the aid of Pandit Damodar Bhat, an erudite scholar of Sanskrit. He also studied the Nilmatpuran and a plethora of Mahatamyas including 'Sharika Mahatamya' and 'Vitasta Mahatamya'. Persian historians like Narayan Koul Aziz and Birbal Kachru and travel accounts of foreign travellers could not escape his notice. In order to gain thorough knowledge ofKashmir geography and topography he visited innumerable places of historical and geographical significance in the Valley. His Guldasta-i-Kashmir' gives us a historical account of Kashmir from ancient times to the period of Maharaja Partap Singh. The history is written in free flowing style in Urdu and has impacted the popular mind in a large measure. The prologue to the book informs that the erudite Pandit had sent it to Col. Halride who was the Director of the Punjab Department of Education for his critical evaluation and comments.

That he was invested with the sensibilities of a poet as well is established by the type of poetry he has penned down for posterity to get a feel of the times he lived in. He wrote both in Persian and Urdu. He was a master of mathnavi and the same is buttressed by his 'Gopalnama' in which he dilates upon his externment by the Maharaja from his native place. The legend of 'Hemal andNagirai' was also dilated upon in the mathnavi form and style, but the work is not available. Some of his available gazals establish his capacity to express himself in this form of poetry as well. The gazal at the end of his'Gulzari Fawayid' is translated here to help the readers get a feel of his sensibilities.

What I saw in the world

is God's glory and manifestation everywhere

I saw the world as free

Whatever I saw is subject to death and decay

The breath in a man is not lasting

The breath always I saw fleeting away

In the meshes of the world

I saw close kins getting drowned

I, Khasta, searched every nook

but was unable to find a kin in adversity.

Pandit Hargopal Koul Khasta, as a dominating and innovative personality of his times inspires us even today . With him as our guide and philosopher the exiled Pandit community will certainly emerge out of the crisis for a new political role of giving a tough battle to the forces that are out to separate the state from the constitutional dispensation of Indian nation-state with the aid of Muslim international with its hub in Pakistan.

Tej Narayan Kak - An Appraisal

Translated by M.L. Koul

TEJ NARAYAN KAK who was a writer, poet and deft story writer practically died unwept, unsung and unhonoured. His death on 14th December, 1998 at the ripe age of 84 in the city of Jodhpur failed to earn media attention. Even the literary circles perhaps not acquainted with his trend-setting contributions to the domain of Hindi prose did not moot a simple resolution to condole his demise. In fact, the new generation writers are totally unaware of Tej Naryan Kak who commenced his literary career in post-Dwedi era and made a mark as a pioneer in the evolution of poetic prose as a specific genre.

Prose alone was not his forte. Tej Narayan possessed a variegated genius which found prolific expression in the delicacies of poetry, in the subtle drawal of characters struggling in tangled situations and more than most in the incisive analysis of issues of criticism. His contributions to the manifold forms of literature were published in the contemporary journals and magazines like Saraswati, Madhuri and Sudha. The famous personalities of the stature of Ram Chander Shukla, Shyam Sunder Das, Maithili Sharan Gupta and Prem Chand were unanimous in recognising the prolific genius and tremendous creative faculities of Tej Narayan Kak.

The ancestors of Tej Narayan Kak had migrated to the heat and dust of plains during the tyrannical rule of Afghans in Kashmir. An ancestor of the family, Shiva Narayan Kak, had migrated from the lust-green valley with a view to saving his skin and faith and had settled in the desert lands of Marwar in Rajasthan. The grand-father of Tej Narayan Kak was a man of high degree status who strutted the corridors of power in Jaipur and Udaipur. His uncle. Pandit Dharam Narayan Kak, was the Deputy Chief Miinister of the State of Jodhpur and continued to hold the position till 1946. Having been born in such an aristocratic family, Tej Narayan was well looked after and put to educative processes in the reputed schools and colleges of Allahabad, Lucknow and Nagpur. In addition to a degree in Law, he assiduously earned post-graduate degrees in English and Hindi. With such educational endowments he joined the administrative services of the state of Jodhpur and retired as an IAS officer in 1972.

Tej Narayan took to writing prose right from his student days. He wrote poetic prose which had taken birth in the Dwedi era and flowered as an independent genre during the romantic period. In the domain of poetic prose.

Tej Narayan Kak enjoyed an equal footing with the pioneers of the genre namely Rai Krishan Das, Chatur Sen Shastri, Dr Raghunath Singh and Mrs Dinesh Dalmia. Poetic prose is characterized by the predominance of Rasa and sensibility and can be differentiated from simple prose by its attributes of music, ornamentation and Rasa. ‘Madira’ as his first collection of poetic prose was published in 1935. Two more collections titled as ‘Nirjar’ and ‘Pashan’ were published in 1943 and earned tremendous appreciation from scholarly cricles. Acharya Ram Chander Shukla fully appreciated and lauded the musical prose that Tej Narayan Kak wrote with absolute finesse. Dr Shaym Sunder Das as an erudite scholar and dojen of Hindi literature placed his ‘prose songs’ in an incomparable category, much superior to those who wrote the same type of prose. In his introduction to one of his poetic prose collections Dr Amar Nath Jha candidly appreciated the beauty, ornamentation and subtlety of his writings. Dilating on some samples of his prose Dr Jha lavished all praise on the author for the lucidity of his expression and enrobement of his prose with romantic sentiments and nuances. Tej Narayan Kak started writing short-stories in a period dominated by the awe-inspiring personality of Prem Chand who was a skilled craftsman none to excel him. He won full-throated appreciation as a story writer. His story ‘Myna’ was rated as the best at a short-story session held at the Prayag University Campus in 1935. The Sudha, Saraswati, Madhuri and other journals and magazines went on publishing his short stories till the fourth decade of this century. He was also a master translator. He translated the short stories of Oscar Wilde, Edgar Allen Poe and O’Henry. Tej Narayan was also a poet who had a full feel of his timers. He wrote the patriotic poems after the pattern of poets following the trend set by the prime mover of the era. He also wrote poems pervading with romantic sentiments. Till 1947 his three poetry collections titled as ‘Bansuri’,

‘Mukhti Ki Mashal’ and ‘Jeewan Jwala’ had been published and had drawn attention and appreciation on the part of literary masters. ‘Rakhta Kamal’ contains poems that are replete with patriotic, zeal and fervour. The poet sticks fast to the view that freedom does not come on mere asking but has to be earned with the spilling of blood.

Kis se padi hai jo aayega

Sat Samandar par!

Tere liye layega

Anupam swatantrata uphar!

Kabi kisi ne kutch paya hai

Anunany kar kar hath pasar!

Mukhti milegee tuje hath mai

Tere jag hogi talwar!

Who bothes to come to you

across the seven oceans.

Who minds to come to you

with the unique gift of freedom

Has anyone achieved anything

with hands spread outlike a beggar?

You will gain freedom

when you wield a sword fearlessly.

In the poems of ‘Rakhta Kamal’ Dr Prabhakar Machwe found the tendencies of progressivism which at a later date came to hold sway over the entire realms of poetic expressions. Dr Gulab Rai felt in them the bubbling spirit of revolution. Dr Ram Kumar Verma was so deeply impacted by the poems that he felt obliged to evaluate them as superb in conception and execution. Tej Narayan Kak as a sensitive poet could not avoid the impact of a new trend of poetry which came to be termed as ‘Chayavad’ in the annals of Hindi poetry. In reality, his poetry was multi-layered and multi-coloured. He wrote poems brimming with sensuousness reflecting the deep influence of poets like Bihari and others. He harnessed his poetic faculties and sensitivities to translate excellent poems from many other regional languages. Some such poems are found in his anthology titled as ‘Vichitra’ published in 1949. The poems that are soaked in maddening love relationships between man and woman are a hall-mark of his poetic sensitivities.

In vastrui mai chippi huee

tumhari dehyashti

Aaisi lag rahi hai mano

Jeene megui ke aavaran mai

Chippi huee vidut-lata-ya

Neel sarowar kee lahriyi mai bal khati hui kamal naal!

In these garments lies hidden

your body-form

and appears as if the lightning-creeper

is hidden in a thin covering of clouds

or

Looks like a lotus-stalk

moving to and fro in the blue waters of a lake.

He has seen the rapturous joy of man-woman relationships in the background setting of nature and its sights and sound and he writes-

I am a man

I yearn for the company of a woman.

See that tree

It has entwined a vine, slend and thin,

round its burning bosom.

See that vast expanse of an ocean

it hides numerous youth-bubbling

streams in its lap.

The horizon of the poet encompasses manifold emotions, feelings and stirring sentiments. He imagines of love-fires of his beloved in the descending shadows of dusk and of dense hair-plaits of his love in the dense dark watches of night.

This evening

is colourful like your love

but has the potential to burn.

and this night

is intense dark like your hair-locks.

Tej Narayan Kak gave forceful vent to his patriotic fervour in his poetic outpourings and followed the style of romantic poets. It appeared that he would find it immensely difficult to put his feelings, felt and lived, in Braj which had found extreme refinement at the hands of Surdas. Surprisingly, Kak wrote in Braj and made it a plastic medium for the expression of love, sensuous and voluptuous, in a manner that he rivals Bihari, a brilliant poet of the erotica. The dohas that he has written in Braj are original and vivacious yet they are deeply impacted by the style, manner and thought content of Bihari.

Tej Narayan Kak made successful attempts at translating poems and metaphors into Hindi from their originals in regional languages. He translated the ‘Nasidiya Sukta’ into Hindi and also the hymns addressed to ‘Indra’, ‘Agni’, ‘Usha’s’ & ‘Surya’. He was deft at translating poems from European languages into Hindi. George Russel, Robert Frost and Davis are some of the European poets whom he has translated into Hindi, thus enriching the native languages through such translations. He was highly enamoured of Rabindra Nath Tagore whom he has profusely translated. He was also influenced by Urdu poetry which gets reflected in some of his dohas written in Hindi or Braj. Tej Narayan Kak is known for his experiments in the field of essay-writing and critical appreciation. His essays are collected in a work titled ‘Indradanush’. He has also evaluated four prose-writers of Hindi in a work published in 1983. He was fully aware of the tools that make one a successful critic of literature. Kak lived his life away from public gaze. That is how his death did not get splashed in the media.

Nilkanth Gurtu: The Last Kashmiri Pundit

'Although we wear this sheet with ever so much care, it has to be given up even as it’--Kabir

By Prof. M.L. Koul

TO the utter shock and grief of scholarly circles, Prof. Nila Kanth Gurtu left this mortal world on 18th Dec., 2008, after having suffered the blisters and bruises caused by the Alzeimers disease.

Prof. Nilkanth Gurtu

Prof. Gurtu was a gentleman par excellence. He was a perfect shavite in word and above all highly obliging. He was a perfect shavite in word and deed. He was at peace with himself and peace with the world all around him. He bore no ill-will against anybody nor had others any reason to bear animosity unto him. ‘Ajatshatru’ is the apt word to describe his character, demeanour and manner. I believe he lived his allotted length of life meaningfully, puruposefully and more than most gracefully.

Assiduous pursuit of Sanskrit scholarship, especially the theoretical and esoteric knowledge enshrined in the Sahiva texts was his sole pre-occupation. He possessed a golden heart and a scintillating head. His depth of understanding of the seminal shaiva texts was phenomenal and amazing. Though the borders between a professor and a pundit often blur.

Yet I would call him a pundit, a real Pandit, a historically conscious pandit. In the words of Bhagwatgita, he could be called a 'sthith prajmna' and a 'sanyasi' if sanyas means consciously ignoring ordinary desires that encase and engulf the mind of a man. 'Kamyanam karmana nyasam'.

Prof. Gurtu had a father, who loved Sanskrit lore and learning and was a shaiva practitioner too. He was responsible for moulding his son in such a domain of learning as was shunned by many Kashmiri Pandits because of the existential insecurity caused by the oppressive Muslim rule. He was put to a traditional seminary which alone could shape him out in the field that his respectable father had chosen for his son. It was not a 'run of the mill' decision that the father, a lover of Sanskrit, had made. Despite opposition from near and dear ones, hassled by the father's decision, the decisive will of Prof. Gurtu's father prevailed. And the pupil continued with the curriculum as was prescribed by the then university of the Punjab. The son worked hard to earn the degree of 'Shastri';, equivalent to graduation in Sanskrit, just at the age of seventeen causing consternation in the student population of those days.

Initially Pt. J.N. Dhar and Pt. M.N. Nehru initiated Prof. Gurtu in the general studies in Sanskrit. Pt. Lalkak Langoo and Harbhatt Shastri, awesome scholars of Sanskrit, furthered and deepened his understanding and grip of Sanskrit grammar, linguistics, and aesthetics.

Having earned two masters in Sanskrit and Hindi, Prof. Gurtu joined a government run academic college and rose too the status of a full-fledged professor of Sanskrit. In this capacity he served many an academic institution of the J&K State. Prior to his join the college department, he had a short stint in the Research Department of the state that was set up by Maharaja Ranbir Singh, who was responsible for the renaissance in the domain of Sanskrit learning and research in the state.

Prof. Gurtu was a great scholar of Kashmir Shaivism, which he would always nomenclature as 'Shaivadvai' philosophy of Kashmir as the name, was assigned to this strand of thought by Abhinavgupta, an unrivalled erudite of the said-philosophy. In the specific regime of Shaiva thought Prof. Gurtu was initiated and guided by Swami Laxman Joo Maharaja at the hermitage at Ishber, near the Nishat Garden. He was an ardent devotee of Swami Ji, who infused a bubbling spirit and enthusiasm among his devotees to learn the seminal texts of the indigenous Shaiva though. He was a learned devotee of the Saint of Isbher and naturally got more benefited than many others in acquiring the knowledge of the subject and it is amply authenticated by the books authored by him. He began as a devotee of the saint and died as his devotee. The saint had bestowed such 'shaktipat' on his devotee as had enabled him to leave a fine yarn of the shaiva thought in glittering language and express the subtleties of the though in highly expressive language. To me he always appeared as a Pundit because of his analysis of the issues related to Shaiva thought. He would always start with language, texture and context and then the clarifications and expositions would follow. In one of my brushes with him, I pointed out word and meaning make poetry (Shabada-arthav kavyan), he retorted--word and meaning do make poetry (Shaibda-Arthav Nanu Kayam).

Unlike many other Shaiva scholars Prof. Gurtu had an extensive study of the five schools of Indian thought. Focused on the Shaiva thought as he was, it was with great ease that he could relate the Shaiva positions on broad theoretical issues with the positions exposited in all systems of the Indian thought. He was a great expositor, his explanations would be quite lucid and language apt and selective. He had the skill of an orator to choose his words directly touching the grooves and ridges of the brain-membrane of the audience. His teaching of the Bhagwatgita at the Ishber Hermitage would hold his audience as if in a magical spell. The gift of the gab and perfect understanding of the philosophical issues are what distinguished him from his illustrious teacher, Dr Balji Nath Pandit, who had an equal share in fashioning the cerebral capacities of Prof. Gurtu.

Prof. Gurtu as a theoretician did not rest his oars at the mere knowledge of the Shaiva thought, but as required by the thought itself he was a devotee, a bhakhta, of Lord Shiva. The brilliant verses from Shiva-stotravali of Utpaldev, were on the tip of his tongue and he would recite them lovingly and liltingly as if he were in a recaptures and hilarious flight. Then the explanations would gush out with firm emphasis on Shaiva Bhakti which is certainly a different cup of tea from the types of devotion as are found in other systems of thought. 'Separation' and 'Union' as two phases in the domain of Bhakhti became lucid clear with the quotes from the Shiva Strotravali. Aware of my background he once softly introduced a mantra to me which I could not practise because of the genocide that our community had to face a the hand of the cruel Jehadists. He as an exilee in Delhi continued with his practices and I could not, not because of lack of faith, but because of existential angst and pain caused by a phenomenon of total annihilation. As a high brow spiritualist he took it as a phase in Shiva sport. But thoroughly mundane in approach and premis I took to the writing of history of genocide that Kashmiri Hindus were subjected to since the inaugural of Muslim rule in Kashmir.

Prof. Gurtu could be a masterly guide for any person genuinely interested in attempting to re-orientate a vital figure of the standing of Lalla Ded, a representative of the civilisational and cultural ethos of Kashmir. He knew the skill of textual criticism and importance of the comparative study of available manuscripts in such attempts. As a Head Pandit in the Research Department of the state he had chanced upon a slew of manuscripts of the Amarnath Mahatamya, which he studied and determined the text and published it with a sound Hindi translation and an invaluable introduction. All types of variations in different versions of the text were foot-noted and missing spaces were filled in with the help of other manuscripts. His guidance for everybody was that re-orientation of a text-never means to mutliate the original text or imposed a new matter on the available text.

'Sambpancha Shikha’ is another work of note that Prof. Gurtu assiduously studied, translated the text with Khemraja's commentary into Hindi and lucidly highlighted the Shaiva contest of the original text. As Kashmir has a history of writing Mahatamyas we have a work of the same hue called Harsheshwar Mahatamya. Prof. Gurtu translated the text into English along with an illuminating introduction to the book.

'Spand-Karika' and 'Paratrimshikha' are the two other seminal works of Kashmir Shaivism which the professor studied at the lotus feet of his venerable guru, whose opinions on issues of theory and praxis of the said-philosophy of Shaivism he always upholds as the final word. In the Spandkarika Prof. Gurtu's expository skills stand out and subtle issues and concepts of the thought stand comprehensively explained, exposited and expounded. 'Paratrimshikha' is deemed as the subtlest of the Shaiva works and Prof. Gurtu ably determined the text and translated it into Hindi with copious explanatory notes and expositions that unravel the esoteric content of the text.

Be it said, the publications of the 'Paratrimshikha' with its amazing Hindi translation and profuse explanations was not savoured well by many devotees of Swamiji Maharaja at the Ishaber hermitage. Prof. Gurtu was grievously hurt when he was accused of unravelling the esoteric content for a consideration. He chose me for expression of his hurt sentiments. I expressed lot many empathies to dispel his hurt and carefully chose a language in appreciation of the tremendous work he had done. His temperament was cool and sedate and nothing would flap his temper. But, this development at the hermitage was what he could not bear with. The fact is that his publisher had harvested his book and given him a mere pittance. More than most, he had done a great service to the very philosophy of Shaivism by translating a formidable work like 'Paratrimshikha'. And it should have been recognised by all who mattered at the Hermitage.

Soon after Prof. Gurtu's 'Paratrimshikha' was published Dr. Jaidev Singh who too had studied the work at Swami Ji Maharaja's lotus-feet put it into English. He took the text as the most authentic as was determined by Prof. Gurtu and added his own explanations and expositions to the work thereby making it more useful for a wider section of lovers of Kashmir Shaivism. The work is published and carries an introduction by Dr. Betina Baumer, a devotee of Swami Ji Maharaj.

As Prof. Gurtu was a senior colleagues and I had thick contacts with him, I once expressed my desire to have a nodding acquaintance with the theoretical postulations of Kashmir Shaivism. He took no time in conceding my humble request. A dexterous teacher with a missionary zeal Prof. Gurtu taught me seminal works like Tattava-Sandoha, Shaivsutra, Spandkarika, Ishwarpratibijjna-Vimarsini and some portions of Shiva-Drishti. I could not continue as we as members of Hindu community got uprooted and scattered under the determined onslaught of Jihadis.

I owe a great debt of gratitude to him for the pains that he took to enlighten me with the whole spectrum of philosophical developments in Kashmir. Since he taught me some vital texts with care and deligence I always considered him as my guru and in Shaiva parlance guru is shiva-guru who initiates a pupil in the Shaiva-marg in accordance with his worth. Perhaps, he considered me his worthy pupil when he disarmed Dr. Balji Nath Pandit by telling bhim that his materialist pupil would work wonders thruogh his initiation in the Shaiva thought. Prof. Gurtu prodded me to take up a research project on Somananda's Shivadrishti. At his insistence I had submitted a synopsis to the Rashtriya. Sanskrit Sansthan for approval. But displacement and exile topsyed and turvyed everything we had planned.

Those who are born are destined to die (Jatasya hi mretu druvam-Gita). Prof. Gurtu had all the angelic qualities. But, in the words of John Keats, 'had he not died, he would have been an angel'.

In the end, As a mortal I pray for peace to his soul.

Book Reviews

Lalla-Ded-meri dreshti mai: A critique

By Prof. M.L. Koul

M.A. (Engilsh), M.A. (Sanskrit), M.A. (Hindi), B.Ed.

CONTENTS

1. Possibilities of Lalla Ded Reconstruction

2. Mrs. Bimla Raina - a poet of fantasy

3. Lalla-Ded-meri dreshti mai - an evaluation

4. Sample Survey of Mrs. Bimla Raina's Fiddlings

5. Epilogue

6. References

7. Changes that Bimla Raina has executed

Chapter-1

POSSIBILITIES OF LALLA DED RECONSTRUCTION

It deserves an open-hearted acknowledgement that the treasure-trove of Lalla Ded vakhs have been saved from extinction as a precious legacy by some ordinary yet exceptional individuals who kept them alive in the grooves and ridges of their memory membrane. For preservation and conservation of knowledge it has been a unique method prevalent in India for millennia. The Rigvedic mantras were preserved this way only. Some indologists of immense repute like Griffth and Monier Williams have been lavish in admiring the role of individuals with extra-ordinary memory faculty for preservation of knowledge in an ancient land like India .

Dr. Grierson, an indologist in the British Service, has rendered the Kashmiri Hindu Heritage a great favour by getting the Lalla Ded vakhs recorded from a Pandit, Dharam Das by name, through Dr. Stein and M.M. Pt.. Mukund Ram Shastri, an awesome scholar of Sanskrit lore and learning.

The vakhs as we have them in ‘Lalla vakyani’, despite numerous transmissions from generation to generation, do retain an archaic flavour and complexion. What the actual form of Kashmiri in the times of Lalla Ded was is a complex issue of linguistic polemics and wranglings which remains distance way from a satisfactory resolution. Bilhan, a kashmiri poet and historian living in 10th century A.D., in a morsel of information characterises the form of Kashmiri in vogue in his time as ‘Desh Bhasha’, but does not provide any reliable sample of it. ‘Bhanasur Katha’, and Mahanaya Prakash’ are written in a language form that borders on an ‘apbrahmsa’ with all its phonemic and phonetic characteristics. The linguistic texture of Lalla Ded vakhs appears prima facie at a divergence from the linguistic shape and form of Bhanasur Katha and Mahanay Prakash. The transformation is not far to seek. The transmission of the vakhs from individual to individual and one family to the succeeding families, it happening through generations together, wrought linguistic changes that rubbed off and stole away the archaicness of the vakhs. During the process of transmissions, additions, deletions, replacements and interpolations cannot be ruled out. One who denies it is not on firm ground of history. Despite ravages wrought by time and transmission from generation to generation, Lalla Ded vakhs in Dr. Grierson's collection do have a semblance of pristinity in word, phrase and form. The same vakhs as are available in Gopi Nath Raina's collection, Prof. Koul's and Prof. Parimoo's works on Lalla Ded do have an improvised complexion, yet are not drained off of old flavour and do not present a linguistic scenario that is so modernised that it marks a hiatus between their vakhs and those of Dr. Grierson.

How is it that Lalla Ded vakhs have stood the fury and flux of time and Nund Rishi's shrukhs have suffered a chemical transformation ? The reason, I believe, is that those who religiously preserved the vakhs of Lalla Ded and continued with their cultural transmission through succeeding generations were not driven by religious prejudices and had no hate-soaked motivations to distort and disfigure them to the level that they remained mere caricatures of their originals. If the transmitter, per chance, had vaishnavite leanings, he would interpolate his vaishnavite credos and notions into the texture of vakhs which on an analysis would not be much in disagreement with how Lalla Ded had posed herself on issues of God, man and world. But, contrary to Lalla Ded, the shrukhs of Nund Rishi as are available in an array of popular versions highlight him as one who is cut asunder from his cultural and civilisational roots. As a person, he is overlaid with a massive weight of fibs, fables and figments that pose him as a proselytiser, semitic in approach and precept, a sufi, not a rishi, at variance with his nativity and surrounding cultural ambience. The pristine Nund Rishi is lost. Linguistically, the shrukhs are couched in a language form that bears a modern ring and glitter and appear to have been cleansed of the dross of archaic tinge and tone, word and metaphor. Such an over-riding transmutation of shrukhs can be safely attributed to Muslim zealots who were ill at ease with his indigenous flavour and were keen to present him as a mauzzin, a preacher fully oriented to the foreign content of a ‘guest faith’ and more than most an iconoclast working out the behests of the Kubrawi Sayyid-sufis responsible for the first holocaust of the native Hindus of Kashmir.

My concerted opinion is that Lalla Ded vakhs as are popularly available are in satisfactorily good linguistic form and shape. Any textual appraisal and evaluation is slightly a difficult process as we do not have a written manuscript of her vakhs that could form a firm substratum for any positive attempt at improvision and quality addition. The vakhs that ring sound and genuine seem to brook no interference and the lurking fear that I harbour is that it might open the dykes for a flood of distortions and misconceptions sneaking into the brilliant store-house of vakhs forming our precious bequest. Any change if conceived on the basis of genuine scholarship has to be fully authenticated and cross-referenced. No haphazard tinkering can do. A scholar who is equipped with profound knowledge of linguistics and textual criticism and high level of awareness of the times Lalla Ded was faced with can venture on an effort to improvise upon vakhs qualitatively, not snatch away the brilliant and thoughtful poetry they winnow out. No a priori methods can do. Internal evidence of vakhs, their thought nuances, linguistic shades and style-related flourishes alone can be the parameters to determine the authenticity and genuineness of any Lalla Ded vakhs.

RELIGIOUS CLEANSING OF LALLA DED VAKHS

I am not so complacent as to say that all is well with the world of Lalla Ded vakhs. Many available versions of Lalla Ded scholars do contain in their ouvre some such vakhs as appear at the very first sight foreign to the world-view and experiential dynamics of Lalla Ded. A host of interpolations, interventions, and insertions, deliberately executed, showcase a sinister design to damage and subvert the very native soul of Lalla Ded. The trajectory for Lalla Ded subversion was first laid out by the Kubrawi authors of Rishinamas and Noornamas who under a design made a mish-mash of Lalla Ded vakhs and Nund Rishi Shrukhs. To create a conceptual disarray Lalla Ded was given the nomenclature of an ‘arifa’, which in essentia collides against her status as a Shaiva yogini who as a person was deeply immersed in a quest of discovering shiva and was in an everlasting union with Him, the only source of beauteous bliss and enlightenment.

To pose Lalla Ded as a sufi is either a cunning attempt to appropriate her or to relocate her for a different identity, religious and cultural. Be it told, Sufism in Kashmir is a foreign plant and has had minimal acceptance and recognition. The brand of sufis who entered the borders ofKashmir were literal Islamists and fanatically Sharia-oriented. Their nodding acquaintance with the Indian Vedanta and Buddhism had in no way softened their religious angularities and hard positions with respect to Jihad, Jaziya and the status of dhimmis. If characterised as a sufi, Lalla Ded is made to lose her close affinity and nexus with the cultural and civilisational ethos she happened to be a fine product of.

The ill-conceived efforts on part of literary mullahs are designed to the end of appropriating Lalla Ded through interpolating and smuggling Lalla Ded-type vakhs into the rich archive of her vakhs.

Some specimens of interpolated vakhs are :

1) Dod kyah zani yas no bane

Gamaki Jama ha valith tane

Gara gara phiras Peyam kane

Dyunthum na kanh ti panani kane

2) Tembar peyas kava no Tsajin,

Mas_ras (Mansuras) kava ahanajen gav

Shanten hanz kreya tola-mwala vajin,

Andrim gaha yeli nebar peyas.

3) Kalimay parum kalimay sarum,

Kalimay kachum Panun Paan

Kalimay Hani Hani Moyan Tourm

Ada Lalla Vachus La-makan

---------------------------------

3) Ada gom molum ta zinim hal

But to be precise, the grave peril to Lalla Ded vakhs emanates from a literary organisation, a creature of constitution, put under the charge of a ‘cultural commissar’ chosen and appointed by a dynasty that has aged and grown effete. He unleashed his malicious campaign way back in 1975 when at the opening ceremony of Lalla Ded Hospital he unabashedy talked of Lalla Ded's conversion to an alien faith. To his utter discomfiture an old man leaning against a staff present in the audience vociferously contradicted his absurd claims and challenged him to cite historical evidences and credible corroborations. The cultural commissaar, sallow in countenance, down in guts and tongue, quietly trod down the dias.

The same cultural commissaar, holding a seat on the dias, ventilated his hallucinatory condition of having seen Lalla Ded's grave at Bijbehara. The function where the cultural commissar is reported to have given vent to his pathological obsession was organised by Mrs. Bimla Raina for the release of her title ‘Lalla Ded - meri dreshti mei’. But, despairingly, there was no pandit Jia Lal Koul, Jalali in the audience who could have rebutted his hallucinatory assertions and crazy bullying. Hopping in the political circles, the cultural commissar, is reported to have spoken almost crude nothing on Mrs. Raina's so-called work on Lalla Ded and rambled on appropriation of Lalla Ded through malicious fabrications and figmented lies. The same cultural commissar is responsible for partitioning the monolith of cultural mosaic and civilisational edifice of Kashmir through the publications issued out as Muslim Gazettes by the cultural organisation operating on naked sectarian lines.

Yet, I am fortified in my conviction that all malicious attempts made by different brands of cultural commissars and pseudo-historians straddling the portals of academia at religious cleansing of Lalla Ded will not fructify. Lalla Ded as a cultural and civilisational sentinel is impregnable. Her tremendous quest for Shiva, her luminous state of being one with Shiva's supreme consciousness, her experiential fire and fury, her spontaneous flow and cascading expression can comfortably edge out all bogus interpolations and spurious replacements.

Chapter-2

MRS. BIMLA RAINA - A POET OF FANTASY

Mrs. Bimla Raina is a poet and writes Lalla Ded dressed vakhs. Two of her poetical collections ‘Resh Malun Meon’ and ‘Veth Macha Shyongith’ are available in print. Without commenting on the poetic quality of her vakhs I would just say that poetry or any form of literature is and has to be contemporary. A poet who breathes and lives in the milieu of 21st century and evinces obsessive concern about irrelevant themes cannot escape the epithet of a regressive shut up in a canary island where he like a bright, yellow finch atop a perch sings his own tuneful song. Lalla's poignancy, her moral and spiritual grandeur and exceptional assertion to be her own self amidst raging storms of religious bigotry should have mightily sensitised her to the burning themes of her personal uprootment, mass expulsion of her tribe, alientation, de-humanisation of camp-dwellers and cultural onslaught and effacement.

As a poet of live sensibilities her vakhs should have been soaked in the dark shades of a funeral song when brutal Muslim crusaders, Jihadis in Islamic parlance, perpetrated atrocious barbarities and inhuman cruelties on Kashmiri Pandit women like Sarla Bhat, Girija Tiku, Rupawati and a host of women for the simple sin that they were Hindus and had stuck to their faith tenaciously. Her vakh should have burst out into a shrill shriek when Muslim marauders, cruel and brutal, arsoned her parental abode, a veritable mansion, at Anantnag and has been lying in charred ruins. The pathetic eclipse of human values and brutal rise of medieval barbarism at her native place, resh malun to her, do not have any thematic value and relevance for her poetic out-pourings. Acrid hatred and religious intolerance enveloping and encasing Kashmiri society do not vibrate within the orbit of her perceptions. As a bruised and traumatised soul languishing in the agonies of exile and banishment I urge Bimla Ji ‘to go out of the house into the convulsions of the world, out of history into history and awful responsibility of the time.’

To quote Bretcht - could there be singing in dark times / yes, there will be singing of dark times.

When Lalla Ded resonantly sang out her vakhs, she was in complete harmony with the spirit of the times. Her vakhs, thoughtful, intense and esoteric in import, are creative ‘statements of spiritual experiences, lived and felt and guides to that experience’. As the epitome of indigenous ethos, Lalla is all embracing, coherent and sweeping, profusely exuding unflinching confidence and deep sense of pride in her heritage and identity. Irrigating the fields of Rishi-ethos with its roots embedded in the Vedic Age Lalla Ded sharpened the cleavage between a tolerant and catholic ethos and a heresy-hunting creed. She fined-tuned her thought when others were sharpening their weapons of force and coercion. In sharp defiance of what was alien she renewed a new force of humanism that was inherent in the indigenous ethos. She soars into the ‘invisible worlds’, it is from the earth she soars. Lalla Ded is great and is stunningly creative.

Chapter-3

LALLA DED - MERI DRESHTI MEI

Mrs. Bimla Raina's another book ‘Lalla Ded-meri dreshti mei’ is said to be the Hindi variant of her Kashmiri book - ‘Lalla Ded-myani nazri manz’. As the grape-vine has it, an urdu version of the same book is under preparation across the Bannihal Tunnel. In absence of the original and its urdu version my critique will focus on the Hindi variant that contains call it a preface by Mrs. Raina and an introduction by Dr. B.L. Koul, a retired professor of Hindi of Kashmir University.

In her pre-face Mrs. Raina makes an astounding statement that Lalla Ded being a yogini par excellence should be appraised beyond the parameters of ‘panth’, ‘Jati, sampradai’ or even the world-view that she has assiduously cultivated and garnered. This, in sum, means to denude her of biographical terrain- her persona, her vicissitudes in mundane life, her trajectory of cultural up-bringing and her arduous struggle to recognise her spiritual destiny. To me, it is a non-literary statement aimed at stripping away Lalla Ded of her identity, personality and tremendous grasp of the delicacies of thought to which as a superb poet she was wedded to. ‘Know the person behind the book’ is a platitude not to be overlooked.

If Mrs. Raina's parameters for literary evaluation, per chance, were applied to John Milton, Dr. Iqbal, Sant Tulsi Das and a host of greats, they, I believe, will get faded into nullity.

Dr. B.L. Koul is all plaudits for Mrs Raina, who, he opines, has given him a book on Lalla Ded resuscitation as per the canons of textual criticism and linguistics. I am afraid I may be dubbed as impolite when I debunk the claims of Dr. Koul and say that Mrs. Raina's work is ten leagues away from textual criticism and linguistics. I would have felt highly obliged had Dr. Koul informed the wide circle of Lalla Ded scholars and lay readers about Mrs. Raina's personal achievements and expertise in the regimes of textual criticism and linguistics, two highly specialised fields.

DR. GRIERSON'S LALLA - VAKYANI

As recorded by all Lalla Ded Scholars, most of them of eminence, the fact about Lalla Ded Vakhs remains that Dr. Stein of the Rajtarangini fame, and Maha-mahopadyay Pandit Mukund Ram Shastri, Director of Research, JandK Government, recorded the vakhs from a Kashmiri Pandit living at Gushi, now destroyed by the Muslim marauders, at the behest of Dr. Grierson. Having put the repertoire of vakhs to his incisive and clinical scrutiny, Dr. Grierson published them under the title ‘Lalla Vakyani’ along with his comprehensive introduction and explanatory notes for which sufficient and copious aid-materials were supplied to him by Dr. Stein and Maha-mahopadyay Pt. Mukund Ram Shastri, his two close associates. What I want Dr. Koul to make note of is that the remarkable Pandit of Gushi had received the vakhs of Lalla Ded set in a sequence by way of cultural transmission and as a man gifted with uncommon memory he had carefully preserved the repertoire on the slate of his memory. The vakhs which the Pandit recited, declaimed or uttered in presence of two eminent scholars were in no way from any written manuscript. So, the vakhs as published by Dr. Grierson cannot be taken as a recension of the Lalla Ded Vakhs. Because of immense popularity of Lalla Ded as a shaivite visionary and practitioner, there were many Kashmiri Pandit families that had received and preserved her vakhs as a cultural bequest and with the advent of printing press some pious Pandits in an admirable effort got them published in vernacular with good translations and explanations of the vakhs. So, all such collections too cannot be taken as recensions of Lalla Ded Vakhs.

METHODOLOGY OF TEXTUAL CRITICISM

The methodology of textual criticism comes into play when a number of manuscripts or published recensions of a particular work are available and an expert with profound grounding in the language and script of the manuscripts or their published variants establishes the authenticity of the work, its language, its content and context and any insertions and changes if made to fill in the moth-eaten spaces on the basis of a comparative study. What is of prime importance is the well-founded awareness and knowledge of the methodology of comparative study of manuscripts and that is the recognised gate-way to sift and sieve the chaff of insertions and interpolations from the grain of authentic content and linguistics of a particular work. The methodologies worked upon by Dr. Stein, Dr. Ved Kumari Ghai, Prof. Nila Kanth Gurtu and Prof. Sri Kanth Koul to determine the authentic texts of Rajtarangini, Nilmatpuran, Paratrimshika and Jonraj's version of Rajtarangini are instructive in this behalf. It has to be thoroughly understood that it is not and cannot be the job of a callow mind.

SILENCE ABOUT THE BASIC MANUSCRIPT

The method employed for linguistic and textual retoration of Lalla Ded Vakhs by Mrs. Raina in her book is both puzzling and mind-boggling. She has not made it known as to which manuscript, ancient or modern, she takes as the baseline for making rapacious forays into the vakhs that are available in various versions. It is possible she might have chanced upon some such manuscripts as Dr. Koul informs the lay and the learned that she has scoured vast swathes of the country in search of research materials for her illuminating work. Dr. Koul or the author herself should have made a definitive mention of it so that a treacherous critic could have acquired, if not so, at least critically scrutinized the manuscripts to assess their authenticity and genuineness or just to check their credentials and worth.

SEVENTY-NINE VAKHS - HANDLED - MISHANDLED

Mrs. Bimla Raina has treated seventy-nine Lalla Ded Vakhs in all. She has quoted versions of the same vakhs as are found in the two brilliant works on Lalla Ded by Prof. Jaya Lal Koul and Prof. B.N. Parimoo. She has not missed to draw upon Dr. Grierson who has included 108 Lalla Ded vakhs in his collection of ‘Lalla Vakyani’. Then, we are given Bimla Raina- branded Lalla Vakhs, of course, with explanations and interventions she has the temerity to make and references galore to Prof. Koul's and Prof. Parimoo's versions of the Vakhs.

VAIN ATTEMPT TO RE-ORIENTATE VAKHS

As an ardent student of Lalla Ded vakhs I feel that Mrs. Raina has not made an in-depth study of Lalla Ded vakhs and more than most, the two classical works on Lalla Ded by Prof. J.L. Koul and Prof. B.N. Parimoo. For reasons unknown she has not tried to know and understand the comparative methodology to arrive at changes she is keen to introduce in the text of vakhs. What exposes her immaturity as a critic is that she has not left even the brilliant vakhs without staining them and I am compelled to say that she is not even remotely conversant with the Shaiva world-view and praxes and their divergence from other strands of philosophical stipulations and practices. The type of vakhs she has framed after cynical changes are not authentic in any wise.

Once tamperings are made, she has not cared a wee bit to weigh whether those are organically in sync with the body and soul of the vakh or jell with it. Her out of context insertions appear as anti-bodies in the texture of the vakhs. To my dismay, I could not find a single tampering, tinkering or replacement that could be considered relevant or genuine to the context and tenor of the vakh. I am flumoxed by the manner she splits a word and constructs new words that are far-fetched and not relevant to the spirit of the vakh. Mrs. Raina is a word-splitter and with such skill at her disposal the vakhs she has structured detract verbal music, tone and tenor, context and structure of the original vakhs that are available in various versions of Lalla Ded vakhs. Whatever interventions she has tried to introduce, one must not hesitate to say, are, on the whole, superfluous, shoddy and crude.

FAILURE TO APPRECIATE LALLA DED AS A POET

As Bimla Ji happens to be a poet she should have appreciated that Lalla Ded is not only a Shaiva yogini, but also an immaculate poet. She has dexterously objectified her mystical experiences and spiritual impulses, though subtle and nebulous, through the flavour of her mother-tongue. She is suggestive in her expression and artistic in poetic ornamentation. Through simile, metaphor and apt word she has woven the mosaic of her vakhs that have a magical effect and prismatic charm. Her bold and concrete images drawn from ware of life are creatively vehicled to suggest the grandeur of her thought founded on a robust theoretical background. The vakhs are not designed to expatiate the categories of Shaiva thought which like all thought architectures are dry as bare bones, but they vibrate to ventilate her bitter moments of life, spiritual yearnings, deep sense of quest, joys and sorrows of an existing individual and celebrate her elevation to the status of a recognised soul. Hers is an immortal voice that gives spiritual succour and strength to amply authenticate human condition. The intrinsic cosmic force of her vakhs is the raison detre for the resilient survival of Lalla Ded as a yogini and poet through ravages of time and choppy waves of religious bigotry. She is home-spun like a shawl. ‘Mystical lark’ as an apt coinage of Prof. B.N. Parimoo does illustrate what essential Lalla Ded is. As an ace poet she touches our tender hearts, enlarges our perceptual field and horizon and uplifts us to a luminous state of self-recognition.

HINDI TRANSLATION OF DISTORTED VAKHS

The Vakhs that Mrs. Raina has framed through her fanciful tinkerings are an ersatz of the vakhs that do carry a deep imprint of Lalla Ded signature. As the vakhs are despairingly dwarfed and impaired, their translation into Hindi by Dr. B.L. Kaul has diminished in a large measure Lalla Ded's literary, philosophical and civilisational stature and prominence.

It is an established fact in literary criticism that poetry suffers serious losses in translations. The poetry in one language if translated into any other linguistic idiom loses its lyricism, tone and tenor, syntax and structure. The losses are inestimable when the original content as matter of translation has been subverted. A scholar like Dr. Koul has chosen to translate such subverted contents into Hindi, the national language, for a wider circle of Hindi readers. It is quite natural that his translation of subverted vakhs will equally be subverted and hence can no longer contribute to the renaissance of Lalla Ded on a broader cultural swathe of the country. No cultivated student of literature could have afforded to ignore the brilliant and focused translations of Prof. J.L. Koul and Prof. B.N. Parimoo who have successfully resurrected Lalla Ded into the linguistic nuances and culture of an alien tongue through their skill and grasp of the contents. It is amazing how Dr. Koul has missed to fathom that Mrs. Raina has not studied the vakhs ‘inferentially, analytically and critically’ and has just skimmed, filleted and cherry-picked some vakhs to stud them with her immature insertions and tinkerings without dilating on solid references to reinforce the changes that she has stipulated and executed.

AAYAYI VANIS TA GAYI KANDARAS

Came she to a grocer, went she to a baker

A Constructed Myth

I feel really anguished when I write that Mrs. Bimla Raina is blissfully ignorant of the seminal historical developments in Kashmir . She is a psychological dupe to a myth, a figment and a prejudiced account as enshrined in the supercilious ‘cultural construct’ that she has unnecessarily chosen to refer to .

The foreign brand of Sayyid-sufis from Hamadan , Gilan and other urban areas of Persia , who entered Kashmir for conversionary activities during the rule of Muslims were essentially colonisers in their approach and premis. To achieve their ends in Kashmir they conceived and devised all unholy strategies to downgrade the natives and their cultural and civilsational hall-marks. As Muslims had captured state power, the Sayyid-sufis, though central Asian in their origins, but thoroughly semitised, considered political power as the sure base for propagation of their foreign faith. Acting out their role as political ideologues and religious proselytisers they manipulated their access to the seats of political power through cryptic and unworthy methods and instilled the spirit of crusade (Jihad) as a matter of religious duty in the mindscape of Muslim rulers. A notable sayyid-sufi from Hamdan delineated a lurid blue-print for the total annihilation of the natives and the same was given in the form of a fiat to the Muslim ruler for an immediate execution. As candidly detailed out in the Rajtaragini of Jonraj and History of Kashmir of Hasan, to mention only a few, the Muslim rulers at the sheer instigation and prodding of the foreign brand of Sayyid-sufis embarked upon the sinister path of destroying the cultural and civilisational signs and symbols of natives.

To write the full script of genocide, the Muslim rulers forcibly converted the Hindus, demolished and arsoned the gigantic temples, molested and set afire the penance-grooves of indigenous rishis and replicating their Muslim history burnt books or dumped them into wells and other water bodies.

To justify the aggression and holocaust the Sayyid-sufis operating in consonance with the Muslim state power abominably demonised the native Hindus as animists, polytheists and heretics. They did not fail to harness colonial anthropology as a weapon to denigrate, humiliate and dominate the natives who had generated a sense of absolute inferiority in the psychic-frame of the orthodox Sayyid-sufis through their ouvre of monumental works on all segments of human knowledge and their cultural grandeur as manifested in gargantuan temple structures.

As Lalla Ded was a living Hindu Icon, fibs and fables, flippant and irreverent, were artfully forged to denigrate her as an ascetic wandering semi-nude through lanes, bylanes and thorough-fares of Kashmir . ‘Aayayi vanis ta Gayi Kandaras’ is one such fib that highlights the hateful perception of the foreign immigrants about the subjugated natives as denizens of a gulag.

The fib relates :-

Lalla Ded was wandering aimlessly on a road leading to the town ofShopian . Observing a man coming from that direction she is said to have yelled that she was seeing a man first time in her life. So, being nude or semi-nude, she hithered and thithered for shelter to cover her body. Having entered a grocer's shop for a shred of cloth, she left it in a huff and headed hastily towards a baker's shop. Finding the lid away from the blazing oven, she plunged into it and after a while is said to have emerged from the burning oven dressed in celestial robes.

Implicit in the fib is the colonial anthropology that Lalla Ded symbolising the religious and spiritual personality of the natives was a half-dressed tribal of the stone age roaming about unmindful of her normal requirement of wrapping her body. Prior to her having a meeting with the foreign fugitive she was required to robe herself as per the decent ethical demands. Being a foreigner the fib extols him as the only alpha male and the whole species of natives decrepit and deficient in potency. Overlay the fib with a spiritual veneer, it is interpreted that the foreigner was an apotheosis of high spirituality who entered an area of darkness where people were only at a primitive level and needed the light of spirituality, besides shreds of cloth to wrap their bodies with.

In his classical work on Lalla Ded Prof. Koul has not missed to mention this derogatory myth, but has given it an amazing historical twist. Possessed of a scintillating intellect and historical awareness, Prof. Koul records that at the sight of a foreigner Lalla Ded plunged into the blazing fires of an oven and emerged robed in celestial raiment reminding the ‘mardi kamil’ about his clandestine escape from his native land to avoid fire-test instituted for him and his whole tribe by Timur, a Muslim ruler and establishing her own credentials as an accomplished lady of spiritual powers capable of braving the same fire-test with her bodily frame intact and unimpaired.

Historically, as per the Muslim chronicle, Baharistan-i- Shahi, the Sayyid-sufi, extolled as the ‘mard-i-kamil’, is responsible for the destruction of the Kali Temple in the heart of Srinagar and issuance of death-warrant against the natives if they dared flout any of the twenty conditions delineated for the kafirs to abide by.

Mrs. Raina should have researched the myth with a view to understanding the derogation and denigration implicit in the fib floated by the foreign colonisers for consumption of the mass of neo-converts and expressed her vociferous detestation against such a snooty and zenophobic construction now deeply etched on the wounded psyche of the statistical Muslims.

As a master of de-constructing a word by split method, she has fragmented ‘kandur’, baker, into ‘kah andar’ leaving the Lalla Ded readers in reeling consternation. ‘Vanis’, grocer and Kandur, baker are hyphenated to convey all in the myth . If kandur is broken into ‘kah andar, inside the eleven, if she means the same, vanis, grocer, demands a Bimla Jian split to create an artificial and tenuous nexus. The entire myth or fib deserves whole hog rejection without giving it legitimacy or credence in any form.

Chapter-4

SAMPLE SURVEY OF MRS. BIMLA RAINA'S FIDDLINGS

Aami pana sodras navi.............

Vakh72

Aami pana is replaced by omapana. All Hindus from north to south of India know that Om is a bija mantra and a seeker meditates upon it for final bliss of unity. When initiated into the spiritual instrumentality of Om , a seeker is all blithe and has no reason to be in despair and dejection. His groping for a beacon to lead him onto the highway of shiva ceases. He knows the key and hence is upbeat with joy. He has only to work out the bija mantra with effort and dedication.

Replacement of ‘ami pana’ by ‘om pana’ mars the entire tone and tenor of the vakh.

Shiva va Keshava va jin va ....................

Vakh 70

The well-known word Jin is tinkered with. It has been de-constructed into ‘ya zi’, which is ridiculous. Jina is a name in vogue for Mahavir and Buddha. It is a fact that Jainism had no stint in Kashmir, but Buddhism had a protracted history in our motherland and has left a profound imprint on the intellectual and spiritual thought-scape of Kashmir . It is equally known that Buddhism was the essential motivational force for the Shaivite thinkers to mould their thought and yogic praxes.

Jina is the pali version of Sanskrit word Jita which refers to Buddha as one who has conquered his external senses.

Then, again, bhava ruja stands replaced by bhava raj. Ruj is derived from Sanskrit word ‘ruja’ meaning disease. The word has been thoroughly discussed by Prof. Koul in all its ramifications. He refuses and rightly so to accept its meaning as disease for the valid reason that Shaivism is all through a philosophy of affirmation. His translation and explanation of the word ‘bhava-ruj’ is sickness of the world caused by duality.

The last line of the vakh is musical, lyrical and lilting and has been replaced by a line that is ponderous, boring and lost to music.

Lalla had a tremendous theoretical grounding in the subtleties of Shaiva non-dualism. But she has not exposited Shaivite theories in her vakhs. She is a yogini, a practitioner, who had her spiritual journey. She is a superb poet too and knows to chisel words to objectify her intense experiences. Lalla Ded is not Abhinavgupta, somanand or utpaldev.

She makes a frequent use of the word ‘shuniya’ which actually has come to the shaivites as a legacy from Buddhism. But, they have incorporated the word for conceptualisations at variance with its Buddhist shade of semantics.

Goran dopnam kunnuy vachun...................

Vakh 15

The word vachun has been replaced by vakhchun. Why ? What necessitates the replacement ? Textual criticism does not mean a whimsical change. Vachun is directly drawn from Sanskrit and has suffered a pronunciational change in Kashmiri. The word vakhnai is a modern coinage from Sankrit word ‘Vyakhya’ and is a word with different connotation.

Vakhchun is also a heavier word than vachun and clogs and disrupts the harmony of the vakh.

The replacement of the expression ‘nanguy nachun’ by ‘nihanguy nachun’ is beyond normal comprehension. Explaining the meaning of the coinage in Hindi, one wonders whether a dance is footed with a help or a crutch. Can such a dance ever be called a dance ? Dance is the art of a beautiful blend of movements, gestures and expressions. Spontaneity defines a dance.

As Lalla Ded could never have thought of literally dancing naked in a conservative society of the 14th century, there is certainly a need to look for a suggestive meaning which in sanskrit aesthetics is called ‘dwaniyatmac arth’. Lalla Ded is provided with a key to spirituality by her preceptor, so she is all joy and song, hilarious and rapturous. ‘Nanguy nachun’ symbolises her condition of ‘awareness come to her’ and extreme mirthfulness. As Lalla Ded had a sufficient background of Sanskrit language, she has used the word ‘nanguy’, drawn directly from Sanskrit ‘nagan’ in the sense of ‘yatharth rupen’, sachmuch’ in Hindi, ‘pazikinyn’ in Kashmiri.