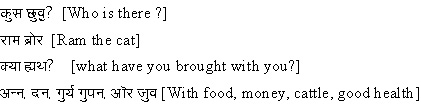

Dr. R.N. Bhat

-

Languages: Kashmiri (mother-tongue), Hindi-Urdu, English, Tamil.

-

M.A.; Ph.D. (Linguistics); M.A.; Ph.D. (Hindi).

-

Professor, Linguistics, Banaras Hindu University- India.

-

Formerly: Chairman, Linguistics, Kurukshetra University (1996-97); Head, Linguistics, Banaras Hindu University (2005-08).

-

Taught at: Kurukshetra, Asmara, Varanasi.

-

Trained at: Kurukshetra, Thanjavur.

-

Books: Authored-One in English, Two in Hindi; Co-edited- Two Volumes. Edited-Two issues of Bhasha Cintana (Research Journal of Linguistics). Essays and book reviews: Over fifty.

-

Research Guidance: M.Phil-3; Ph.D: awarded-3, submitted-1, registered-4.

Our Heritage

Aspects of Kashmiri Pandit Culture

by Raj Nath Bhat

Background

Kashmiri Pandits have been a profoundly religious people; religion has played a pivotal role in shaping their customs, rituals, rites, festivals and fasts, ceremonies, food habits and the worship of their deities. Kashmir is widely known as the birth-place of ‘Kashmir Shaivism’ – a philosophy expounding the unity of Shiva and Shakti. Hence, Shaiva, Bhakti and Tantra constitute the substratum of the ritualistic worship of Kashmiri Pandits on which the tall edifice of the worship of Vishnu (Krishna and Ram), Lakshmi and Saraswati, and a host of other deities has been built.

Kashmir has also been a great centre of learning for several centuries. It hasbeen a major centre of Buddhist learning for nearly a millennium duringwhich period a sizeable number of revered Kashmiri Buddhist scholars travelled as far as Sri Lanka in the South and Tibet and China in the North. The contribution of these scholars commands a place of pride in the extant Buddhist philosophy. Unfortunately, this tradition was brought to an almost abrupt end by the Pathan and Mongol invaders in the 14th century C.E.

Though the advent of Islam produced a clash of civilizations, it also broughtinto being a ‘composite culture’ in which saintly figures (Rshi, Pir, Mot, Shah) came to be revered and respected equally by the polytheistic Hindu as well as the monotheistic Muslim .

This journey through over three millennia has shaped the cultural moorings of the Kashmiri Pandit (KP hereafter) and provided him with a vast corpus of impressions and expressions, which have given him a distinct cultural identity.

Today the KP is on the crossroads, bewildered and baffled, homeless and nameless. His progeny is in a flux, unsure of its morrow and unaware of the traditions that its forefathers held dear to their hearts. This paper records some of the major socio-cultural beliefs, traditions, customs and festivals of the KP with the hope that the younger KP generation will know, learn, and comprehend the essence of KP culture which evolved long periods of peace and turmoil.

Festivals and Fasts

Festivals break the monotony of everyday work and provide the members of a community with an opportunity to feel cheerful, happy and relaxed. Hindu festivals have a deep spiritual import and religious significance and have also a social and hygienic element in them. On festival days people take an early morning bath and pray and meditate which gives them peace of mind and a new vigour.

In their lunar calendar, KPs observe a number of festivals and fasts, most of which fall in the dark fortnight (Krishna paksh). The eighth (ashtami), eleventh (ekadashi) and fifteenth (Amavas/ Purnima) days of both dark as well as bright fortnights, and the 4th day of the dark fortnights (Sankat Chaturthi) are considered so auspicious that people would observe fast on these days.

KP new-year (Navreh) begins on the first day of the bright fortnight of the month of Chaitra. On the eve of Navreh, a thali full of rice is decorated withfresh flowers, currency notes, pen and inkpot, curds, figurine/picture of a deity and (dry)fruits. Early in the morning, the one who wakes up first (usually the lady of the house), sees this thali as the first object in the New Year and then takes it to all other members of the family, wakes them up to enable them to see the decorated thali before seeing anything else. This signifies a wish and hope that the new year would bring wisdom and blessing to every member of the family all through the year.

On the 3rd day of Navreh, the community members go out to nearby parks, temples, or outing spots to enable people to meet each other after nearly four months of snowy-winter. It is a social gathering where men, women and children put on their best attire to get ready for the new year chores. The eighth and the ninth days of the same fortnight are observed as Durga Ashtami and Ram Navami respectively. The fortnight marks the beginning of Spring, an important junction of climatic and solar influences. Durga Ashtami is celebrated to propitiate Shakti to seek her blessing and mercy. The eighth day of the dark fortnights of the Zyeshth and Ashar months are also celebrated with great devotion, when people throng the Rajnya temple at Tulumula (Gandarbal), and Akingam, Lokutpur (Anantnag) to pray and worship Maa Shakti.

The 14th day of the bright fortnight of the Ashara month is specially dedicated to Jwalaji, the Goddess of fire. People in large numbers go toKhrew, 20 kms. from Srinagar and offer yellow rice and lamb’s lung to the Goddess.

Purnima of the Shravana month is the day of Lord Shiva. On this day pilgrims reach the holy Amarnath cave to have a ‘darshan’ of the holy ice-lingam. People also go to Thajivor (near Bijbehara) to pray at the ancient Shiva temple there.

The sixth day of the dark fortnight of Bhadrapada is sacred to women. On this day, known as Chandan Shashthi, women observe a dawn to dusk fast and bathe sixty times during the day.

The eighth day of the dark fortnight of Bhadrapada is celebrated as the birthday of Krishna, the 8th incarnation of Lord Vishnu. On this day people sing in daintly decorated temples prayer songs in admiration of Lord Krishna. They do not eat solid food till midnight.

The Amavasya of the same fortnight is called Darbi Mawas. On this day the family Guru (purohit) brings ‘Darab’, a special kind of grass, which is tied to the main entrance of the house.

The Ashtami of the bright half of Bhadrapada is known as Ganga Ashtami. On this day people go on a pilgrimage to Gangabal. The 14th day of the same fortnight is called ‘Anta Chaturdashi’. On this day the family purohit brings‘anta’ a special thread which married women wear along with 'atûhór', a threaded bunch of silk tied to one’s ear. The ‘anta’ is cleaned and worshipped like a 'Janev', the sacred thread worn by men. The 4th day of this fortnight is dedicated to Vinayak, the son of Shiva. Families prepare special sweet rotis known as 'pan' on this day or during the remaining days of this fortnight. When the'pan' is ready, it is worshipped and the tale of its origin is recited by the eldest member of the family. The rotis are distributed among the neighbours and relations as 'pan naveed'.

The dark half of Asoj is the fortnight of ancestors, pitra paksh (kàmbûripachh). During this fortnight people pay homage to their dead parents, grandparents, great grandparents by performing Shraadha and giving away rice, money, fruits, clothes and other things to the needy.

Mahanavami and Dussehra, marking Lord Rama’s victory over the demon Ravana, fall on the 9th and 10th days of the bright half of Asoj. Episodes from Ramayana are enacted during this period.

Diwali, the festival of lights, falls on the14th day of the dark half of the Kartika month. All the corners, windows, balconeys and eddies of the house are illuminated with lights. It is also believed that Lord Rama returned to Ayodhya on this day and Lord Krishna killed the demon Narakasura; hence, this day symbolizes the triumph of good over evil.

The third day of the bright half of Magara month is celebrated as the day of the ‘Guru’ (Guru tritya). Before the advent of Islam in Kashmir, scholars were awarded degrees to honour their academic achievements on this day (a precursor to present-day convocations). On this day, the family purohit brings a picture of Goddess Saraswati for a new-born baby or a new daughter-in-law in the family. On the Purnima of the same fortnight yellow rice (tåhår) is prepared early in the morning and served as prasad to children and adults in the family.

During the dark half of the month of Posh, the deity of the house is propitiated for seeking his blessings. The deity (dayút) is served rice and cooked and raw fish on any chosen day between the 1st and the fourteenth of the fortnight. On the day of the feast, called 'gàdû batû' , fish and rice isplaced in the uppermost storey of the house late in the evening for the dayútwho is expected to shower blessings on the family.

The Amawasya of the same fortnight is the auspicious day of 'khétsí màvas', when rice mixed with moong beans and other cereals is cooked in the evening to please the 'yaksha' (yóchh) so that he casts no evil on the members of the family. The 'cereal-rice' (yéchhû tsót) is placed at so a spot outside the house, believed to be the yaksha’s place.

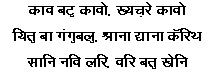

The 7th day of the dark half of the month of Marga is observed as the death anniversary of Mata Roopabhawani and the 11th day of the same fortnight is observed as Bhimsen ekadashi. It is believed, that from this day the earth begins to warm up and snow starts melting. The purnima of this month is celebrated as Kaw purnima (kàv pûním), that is crow’s purnima. On this day, the cup of a laddle like object, 'kàvû pôtúl' - crow’s idol (a square front cup made of hay with a willow handle) is filled with a little rice and vegetables and the children of the family are made to go to the upper storey of the house and invite crows to the feast. The children invite the crows thus :

"Crow pandit-crow, cereal- rice crow

come from Gangabal, bath meditation having done,

to our new house, to eat cereal-rice"

Shivratri (herath) is the most auspicious KP festival. Beginning on the first day of the dark half of Phalgun, its celebration continues for twenty three days till the 8th day of the bright half of the same month. During this period the house is cleaned thoroughly for getting it ready for the marriage of Shiva and Parvati on the 13th day of the dark fortnight.

The 13th is the wedding night when watukh, Shiva in bachelor as well as in bridegroom forms, is worshipped along with the bride Parvati, Kapaliks,Shaligram till late in the night. Watukh, that is, ‘Shiva’s marriage party, is worshipped for four days, upto the 1st day of the bright half of the month. On this day, watukh is cleaned (parmùzún / parimarjan) of all the flower petals etc. at a tap in the compound of the house. Then it is taken back into the house where the eldest lady of the house bolts the entrance-door from inside. The members carrying the watukh knock at the door and the following exchange of words takes place :

... and so on.

At the end of the watakh puja Shivratri prasad in the form of kernels of walnut and roti made from rice flour is distributed amongst neighbours and relatives. The distribution of the prasad is completed before the 8th day of the bright half.

The 11th day of the bright fortnight marks the beginning of sònth (Spring). On the eve of sònth, a thali full of rice is decorated as on the new-year eve to be seen as the first thing on the morning of ekadashi.

Rituals and Rites

The domestic rites and rituals among the Hindus are popularly known asKarma and Sanskara. In the form of Karmas they are cherished as programmes of duty to be observed by all householders and as Sanskaras, these enable the devotee to make their observance rhythmical. The rites and rituals serve the external and internal modes of purity (shrùts). Together they constitute certain ceremonies beginning with the Garbhadhaana or the rite of impregnation and ending with the anteshti or the funeral rite includingShraddha. These can be divided into pre-natal, natal, post-natal, prenuptial, nuptial, post-nuptial, pre-obituary, obituary, and post-obituary.

Marriage

Hindu marriage is not a social contract but a religious institution, a sacrament in which besides the bride and the groom, there is a spiritual or divine element on which the permanent relationship between the husband and the wife depends. The husband and the wife are responsible not only to each other, they also owe allegiance to the divine element. This mystic aspect of Hindu marriage necessitates a number of symbols. The marriage creates a new bond between the bride and the groom. They have to rear up this union by dedicating their entire energy in the direction of their common interest and ideal.

Marriage is possible only between those families which have had no kinship for seven generations on the paternal side and four generations on the maternal side. Once the boy and the girl consent to join as man and wife in a life-long bond, their parents meet in a temple in the company of the middleman (if there is any) and some select family members from both the sides to vow that they would join the two families in a new bond of kinship

This ritual is known as kasam dríy. This is followed by a formal engagement ceremony (tàkh) in which some members of the groom’s family and relatives visit the bride’s place to partake of a rich feast. The party brings a Saree and some ornaments, which the bride is made to wear by her would be sister-in-law. During this ceremony, the two parties exchange flowers and vow to join the two families through wedlock. A younger brother or sister of the bride accompanies the groom’s party with a gift of clothes for the groom.

After this function the two families begin to make preparations for the marriage ceremony which is held an some auspicious day after consulting a purohit.

Several rituals are associated with marriage whose observance begins nearly a week before the wedding day. The bride’s family begins with what is known as 'garnàvay' (literally: get madeup) when the hair of the bride are let loose. This is followed by 'sàtû mänz' (first henna or auspicious henna) when henna is applied to the bride and the groom by their respective mothers and aunts. These rituals are attended by near relatives and neighbours. 'mänzíràt' (henna night) is the first major event when all the relatives-men, women and children in the extended families assemble at the girl’s and the boy’s respective places. This is a night of much rejoicing and feasting. The evening meal is followed by a series of ceremonial acts. Henna is pasted on the hands and feet of the bride and the groom in their respective places and almost every young boy and all women and girls paste henna on their hands and elderly women sing traditional songs. Before pasting henna, maternal aunt (maami) washes the feet and hands of the bride and the groom, and the paternal aunt (bua) applies henna, and the maternal aunt (maasi) burns incence to ward off evil. Meanwhile women, girls and boys sing traditional ditties as well as popular songs appropriate to the occasion.

While the singing, & henna pasting is on, the bride as well as the groom are given a 'kaní shràn' (thorough bath) by aunts and sisters-in-law to prepare them for 'dívgòn', the entrance of Devtas. After the ceremonial bath, the boy and the girl wear clothes brought by their respective maternal uncles. The bride is made to wear 'déjíhòr' - a gold ornament, and 'kalpùsh' -a variety of headgear.

'déjíhòr' is tied to a gold chain known as ‘'ath' which is provided by the groom’s family on the wedding day to complete the holy alliance between Shiva - the groom, and Parvati - the bride.

'dívgòn' is the religious ritual performed after the bath. The family purohit performs a small yajna on this occasion. 'dívgòn', it is believed, transforms the bride and the groom into ‘Devtas’.

On the wedding day, the groom wears a colourful dress with a saffron-coloured turban on his head. He is made to stand on a beautifully made 'vyùg' (rangoli) in the front compound of the house where parents, relatives and friends put garlands made of fresh plucked flowers, of cardamom and currency notes round the groom’s neck. A cousin holds a flower-decked umbrella to protect the groom against evil. Conch-shells are blown, ditties are sung and the groom’s party moves towards the bride’s place usually in cars and other modes of transport.

Conch-shells announce the arrival of the groom and his party at the bride’s place where the lane leading to the main entrance to the house is beautifully decorated with colourful flowers and dyed saw-dust. Upon entering the compound of the bride’s house, the groom is welcomed by traditional songs sung by the bride’s relations. He is put on a rangoli where the bride draped in a colourful silk Saree is made to stand beside him on his left side. There is another round of garlanding from the girl’s relatives. Then the mother of the bride comes with a thali of small lighted lamps made of kneaded rice flour and an assortment of sweets and makes the groom and the bride eat from the same piece of sweet a couple of times. After this the bride is taken back into the house and the groom is made to stand at the main door of the house for a short 'dvàr pùzà' (door prayers). The groom’s party joins the bride’s relatives in a very rich feast. Meanwhile the bride and the groom are seated in a beautifully decorated room for a series of rituals and ceremonies amidst chanting of Sanskrit mantras for several hours with little breaks in between. During these ceremonies, the bride is supported by her maternal uncle. The purohits of the two families recite mantras and make the bride, groom and their parents to perform a number of rituals with fire (agni) as the witness. The boy and the girl take seven rounds of the agni-kund (spring of fire) and vow to live together in prosperity and adversity, in joy as well as in sorrow, till they are separated by death. 'lågûn', as this ceremony is called, is followed by 'pòshû pùzà' (showering of flowers) in which a red shawl is spread over the bride and the groom, held at four edges by four people, and amidst recitation of shlokas all the elderly people shower flowers on the two ‘devtas’. After this ceremony the bride and the groom are taken to the kitchen and made to eat from the same plate.

A 'vyùg' (rangoli) is laid in the compound and the bride and the groom stand on it. Now the bride joins the groom to the groom’s place where yet another rangoli is laid and the bride and the groom are made to stand on it. Here the groom’s party relaxes and the bride is made to wear'ath'', the gold chain which is attached to 'déjíhòr'. Her hair and head-gear 'tarûngû' are tied and she is made to wear a saree given to her by the groom’s family.

After this they return to the bride’s place with a small party comprising the groom’s father, brothers, sisters, brothers-in-law, and a couple of friends. As a member of her new family, she is now a guest at her parent’s place. The groom’s party asks the bride’s parents to send her (the bride) to her family (the in-laws). After a little tea, the party leaves for the groom’s place. A younger brother/sister/cousin of the bride accompanies the party to the groom’s place. On the next day or a couple of days later depending upon the mahoorat (auspicious day), the newly married couple visit the wife’s parents. This visit is known as 'satràt' or 'phírsàl'. Upon reaching the wife’s parent’s place, the man and wife are welcomed with 'àlat' - a thali with water, rice, coins and flowers.

The nuptials in their utterances, promises, and hopes symbolize a great social transition in the life of the bride and the bridegroom. They have to earn their own livelihood, procreate children and discharge their obligations towards Gods, parents, children and other creatures of the world. The nuptial ceremonies these address all aspects of married life: biological, physical, and mental.

During the first year after marriage the girl’s parents send gifts to the groom’s place on a number of occasion in the form of cash, clothes, sweets, fruits, & cooked food. Gifts are sent on the birthdays of the groom, the bride & groom’s parents; prasad in the form of wanlnuts and baked bread etc. on Shivratri (hèrats bòg), fruits, sweets etc. on Janamashtami and Diwali; 'pôlàv' etc. on 'khétsí màvas'; During the month of Magar a special ceremony known as 'shíshúr' is solemnized when the bride is provided with a special 'kàngûr'-a brazier used during winter, and 'shíshúr' (til seeds wrapped in a piece of silk) is tied on her upper garment. On this day, near relatives, especially women, of the groom’s family are invited and the girl’s parents send gifts in the form of clothes, cash, to their daughter.

lath môklàvûni

During her first pregnancy, the girl’s parents invite her to their home, and after a little puja, she is made to wear a new headgear 'tarûngû'. Then accompanied by a sister / cousin, she goes back to her home with milk, clothes, cash, baked bread & other gifts.

sôndar

On the seventh day after delivery, the mother and the baby are given a hot bath. Special vegetarian / non-vegetarian dishes are prepared on the occasion. Pieces of paper or 'búrzû' (birch bark) are burnt in an earthen plate and circled thrice round the heads of the mother and the baby to ward off evil. Seven plates of special food are served to the paternal aunts of the baby. This is exclusively a women’s ceremony. On this day the mother’s parents send ‘trûy phót' (wife’s basket) which contains clothes, rotis, sugar, spices, cash for the newborn, and its parents and grandparents.

kàh nèthar

This is the religious ceremony of purification. On the 11th day after childbirth, a small ‘hawan’ is performed in the house and a tilak is applied on the forehead of the newborn . The baby’s maternal grandparents send clothes on the occasion. This ends 'hòntsh' (impure effect) in the family.

On the 12th day the baby is put on a rangoli laid in the house-threshold (porch) and a piece of sweet is touched to its lips, the family elders shower blessings on the baby. The baby & the mother visit its maternal grandparents where they may stay for a few days. On their return, the grandparents send baked items mutton preparations, curds, milk & clothes for the baby, its parents and paternal grandparents.

mèkhlà or mèkhal

In the past the sacred thread ceremony of boy was performed when he would become seven years old, i.e. when he would be able to wash the sacred thread 'yòní' (jeniv) and recite the “Gayatri Mantra”. Usually, all the boys in the family are made to wear the sacred thread together in a single ceremony. 'mèkhlà' or yajnopavit involves all the ceremonies and rituals, like 'mänzíràt', 'dívgòn'' etc. associated with a marriage ceremony. After 'dívgòn' the boys' (called 'mèkhlí mahàràzû' - mekhla grooms), heads are shaven and they are made to wear saffron-coloured robes.

Mothers, and paternal aunts wear red and white thread 'närívan' on their ears and a huge agni-kund’ is prepared where seven purohits recite vedic mantras for nearly 12 hours and ghee, jaggery, rice and paddy are constantly poured into the agni-kund to please the devtas and seek their blessing. For the whole day relatives and friends come to this ‘'Hawan Pandal' and the eldest of the 'mèkhlí mahàràzû begs of them to give 'dakshínà' (offerings) for the gurus (the purohits), which the visitors are pleased to give him 'åbìd' (dakshina). Towards the evening the family-purohit asks the father of the mekhla grooms to put the sacred thread on them. This is a very emotional moment for the purohits as well as the father, the members of the family, and relatives. The chanting of mantras rises to the highest pitch and the mekhla-grooms are made to wear the sacred thread, marking their entrance into the pure brahmanical fold. This begins their brahmachari period, the first stage of Hindu life, when they seek only knowledge and wisdom. After this the Guru (family-purohit) whispers the Gayatri Mantra into the ears of the mekhla grooms. They are directed to recite this mantra every morning after taking a bath.

Once the yajna is concluded, the maternal uncle(s) of the mekhla –grooms takes them to a nearby temple. Meanwhile prasad in the form of rice, cereals, vegetables is served to all the relatives and friends including the mekhla grooms, and their parents who observe a fast for the whole day.

The next day (kôshalhòm) is observed as a day of feasting when mutton preparations are served. A day or two later, depending upon the position of the planets, sweet rice 'khír' is prepared and a small puja held. After this the mekhla-grooms are made to put on a new sacred thread and the mothers and the aunts remove the 'närívan'. This brings to an end the rituals connected with the yajnopavit ceremony.

Death rites

When a person breathes his / her last, his/her mortal remains are washed in water to which Ganga jal is added. Cotton buds are put into his / her ears and nostrils. A coin is placed at its lips. The whole body is covered in a white shroud and tied with a thread (närívan). The body is then placed on a plank of wood and four persons take the coffin on their shoulders to the cremation ground. The eldest son of the deceased carries an earthen pitcher in his hand and leads the coffin. Some distance away from the cremation ground, the coffin is placed on the ground and the family members, relatives and friends are allowed to have a last glimpse of the deceased’s face. The coffin is then taken to the cremation ground and put on a pyre. The eldest son, after taking three rounds around the pyre, lights it. From second to the ninth day of one’s death, his/her eldest son and daughter come out on to the house threshold before sunrise and call upon their departed father/mother a couple of times, asking him:

bôchhí mà låjíy babò / mäjì?

(Are you hungry father/mother?)

trèsh mà låjíy babò / mäjì?

(Are you thirsty father/mother?)

tür mà låjíy babò / mäjì?

(Are you feeling cold father/mother?)

On the fourth day of cremation the sons and some relatives and family friends go to the cremation ground to gather ashes (åstrûk). Most of it are immersed into a nearby river /stream and a part is put into an earthen pitcher and taken to Haridwar for immersion into the holy Ganges.

On the 10th day, the sons of the deceased along with many relatives and the family purohit go to a river bank where sons’ heads are shaved and a Shraadha is performed. The relatives after having lunch leave the family of the deceased alone. On the 11th day, the sons and daughters perform a very elaborate Shraadha under the guidance of a purohit. The ceremony ends with aahuuti given to agni invoking almost all the deities, major rivers, temple towns, mountains, and lakes of South Asia. On this day the daughters too pay dakshina to the purohit and arrange food for the families of their brothers.

On the same day, ‘oil’ is provided for the deceased (tìl dyún) in which mustard oil is poured into a large number of earthen lamps and cotton wicks are immersed and lighted in them. Favourite vegetarian foods are prepared in the name of the deceased. Burning of oil lamps is meant to provide light to the deceased in the ‘other’ world.

Another Shraadha is held on the 12th day after death. This marks the end of the mourning, when married daughters return to their homes.

During the first three months, a Shraadha is performed after every fifteen days i.e. on the 30th, 45th, 60th, 75th and 90th day of death . An elaborate Sharaadha is held on the 180th day (shadmòs). The Shraadha on the first death anniversary (våhårûvär) too is an elaborate one. Daughters and sons and their husbands/wives assemble to perform both shadmòs and våhårûvär.

After this a Shraadha is done every year on the death anniversary and one during the pitra-paksh. The children (sons and daughters) offer water to their deceased parents and three generations of grandparents every morning.

Language and food

KP has been a polyglot throughout the known history. Besides mother tongue (Kashmiri) it has had a sound knowledge of Sanskrit, Persian, Urdu-Hindi, and English at different periods in history. Literatures of these languages are a testimony to their genius and creativity. Their original contributions in the areas of philosophy, theology, aesthetics, logic, grammar, astronomy etc. occupy a place of pride in the extant literatures of these disciplines.

KP loves vegetarian foods yet mutton and fish have been its favourite. Rice and knolkhol (hàkh batû) has been its primary requirement. The use of a wide variety of spices, e.g. aniseed powder, turmeric powder, chilly powder, ginger powder, black-pepper, cardamom, saffron etc. is very common among the KPs. Besides knolkhol, KP relishes beans, potato, spinach, lotus-stalk, sonchal, raddish, turnip, cabbage, cauliflower, wild mushroom, cheese and an assortment of local greens like lìsû, vôpal hàkh, núnar, vôstû hàkh and hand. The major mutton preparations of the KP include: kålíyû, ròganjòsh, matsh, kabar gàh, yakhûni, rístû, tabakh nàt, tsók tsarvan etc.

To Conclude

After the advent of Islam in the Valley, when Persian replaced Sanskrit as the language of administration, senior members of the Pandits (a large majority had been forced to embrace Islam) organized a kind of a conference to deliberate on and find means to preserve their religion and culture so as to prevent it from becoming extinct. In that historic conclave, it was decided that in order to participate in State administration, it were necessary to learn Persian, so the son’s son would learn the language of administration and the daughter’s son, if he were educated by his maternal grandparents, would learn bhasha ‘Sanskrit’ and religious scriptures and eventually perform religious rites and rituals. Thus, two distinct sects, one of bhasha Pandits or purohits ‘clergymen’ and another of the karkun ‘the men of administration’ were created. In course of time the Purohit became dependent upon the Karkun for dakhshinaa ‘offerings’ to make his living and the Karkun came to be considered a superior class to the men of religion. This historic ‘decision’ has brought the community to an impasse now where the purohits too have diminished in number and the very identity of the community is at stake. At this juncture, it is not only the religious rites and rituals, customs, festivals and ceremonies, beliefs, myths and superstitions that are under threat of extinction, but also their mother tongue, which was not under threat during the Muslim period.

The community elders need to sit together again to think about its linguistic and cultural heritage and evolve a strategy to preserve it. Otherwise, the literary and religious writings of Laleshwari, Parmanand, Zinda Koul will have no takers in near future.

Displaced Kashmiris: A Study in Cultural Change 1990-2002

by Raj Nath Bhat

This paper investigates the liguistico-cultural loss among the younger generation of the displaced Kashmiris who have been living away from the valley for over a decade now. This segment of the population was either of a tender age at the time of displacement or was born in the plains. Although it lives with the middle generation (parents) who are well conversant in Kashmiri language and culture yet a lack of motivation on the part of the parent as also on their own part has made them mere passive users of the language. Hindi has acquired the status of their first language both at home as well as at the school. The parents are deeply pre-occupied with their daily chores to win bread and butter for the family. They have neither the time nor any inclination to enable their children to get acquainted with Kashmir language and culture. The community extends no support whatsoever whereby the Kashmiri language and culture could be taught to them. Hindi is the language of the dominant culture and English that of higher education. Kashmiri finds no place in this kind of linguistic hierarchy. The younger generation is least inclined to learn and comprehend their parental cultural and tongue. Rather, it, in their view, is a burden they can do well without. Obviously, the loss of both the language and culture looks inevitable.

Introduction

Language and culture are the two fundamental ingredients which give a community a distinct character and build bonds of fraternity and oneness amongst its members. The climate, flora and fauna, history and the geographical conditions of the place where a community lives govern many a cultural entity. Kashmir has a cool climate where the spring is flowery and the winter snowy. The towns and villages are full of brooks, rivulets, rivers and springs. One has a geographical understanding of the directions (east/west etc.) due to the hills and mountains surrounding one’s place of residence. All such objects are lacking in the plains. Kashmir valley is full of orchids of almonds and apples, Chinar and walnut trees are usually grown in the kitchen gardens/backyards. There are several kinds of flowers-wild and cultivated, foods, places of religious significance etc. which may not be found in the plains. A displaced community finds itself in alien surroundings with a new kind of flora and fauna and language and culture. Several linguistic-cultural entities are inevitably lost in this scenario because the younger generation cannot get acquainted with the climate, flora and fauna, and culture of its parental (ancestral) land. Thus a large number of linguistic-cultural entities are lost even in the passive competence of the younger generation of a displaced community.

Background

During the medieval times when the Muslim kings inflicted terror in the lives of Kashmiris, a large majority embraced Islam and a few who stood their ground, despite repression, sought protection as well as guidance from Guru Tegh Bahadur, the ninth Sikh Guru, whom the barbaric Mughal King beheaded in Delhi, and his martyrdom prevented the Kashmiri Hindu culture from going extinct. In the modern times, the religious and cultural heritage and identity of a people does not attract the attention of the powers that be unless they constitute a numerically strong group capable of doing or undoing governments. Pandits of Kashmir constitute a miniscule minority of nearly half a million people, in the vast human jungle of India, which does not send even one member to an assembly. Obviously there is none to take up its cause. On the contrary, there are forces determined to wipe it out from the cultural scene of India. ‘Scholars’ and politicians have been observing an intriguing silence regarding the displacement of the Kashmiri Hindus. The cultural identity of this community is gradually getting eroded which over the ages has been at the forefront in shaping, nourishing and nurturing the ‘great Indian culture.’ An authentic history of the ‘making of India’ would always have to repeatedly refer to Kashmiris’ contributions to ancient Indian knowledge, be it philosophy or religion, logic or literary theories, astrology or mathematics, history or grammar. The rightful heirs to the legacy of Kalhana, Abhinavagupta, Laleshwari, Bilhana, Kuntaka,Vamana, Shankuka and a host of other stalwarts is on the cross-roads today, bewildered and baffled, unsure of its future.

Migration away from Kashmir of the members of this community has been a continuous process ever since the advent of Islam into the valley. The terror and torture inflicted upon this community by the Muslim rulers sends shivers down one’s spine. The names of Sikander (the idol-breaker), Aurangzeb, Jabbar etc. continue to be the terror-creators in the folklore of the community.

A few that possessed “the imagination of disaster” probably guessed (and rightly so ) the intent of the post-independence rulers because the migration of the members of the community in ones and twos continued during the years after independence (1947). But the winter of 1989-90 turned out to be the turning point in the history of this community which constituted a mere 2.5% of total population ( of the Muslim majority Kashmir valley) - nearly 300,000 souls of various age groups, social strata and professions.

In order to build an Islamic society in Kashmir valley, the leadership of this movement offered three options to the minority Hindus : rålív ‘embrace Islam’, tsålív ‘run away’ natû ‘or else’ gålív ‘perish/face annihilation’. Killings of prominent Hindus like lawyers, businessmen, judges, professors, government officers etc. followed . ‘Human Rights’ groups found no case of the violation of human rights! Powers that be seemed indifferent. By November 1989, the Muslim terrorists came forward with yet another insulting slogan which read : así chhú banàvún päkístàn, batav bagär,batûnêv sà ‘we shall join Pakistan, without Hindu men but with Hindu Women’. Meanwhile the killings of even less prominent members of the community continued. By December 1989, the Pandits of Kashmir started running away to Jammu, Delhi etc. to save their lives and honour. The valley in her sad history of the last 600 years, once again witnessed the exodus of its original inhabitants with a 5000 year old history. And by driving the minority community out, the process of ethnic cleansing in the valley was complete. Human rights groups observed a sacred silence. Ironically, the posters on Delhi walls during the period read: “Hands off Kashmiri Muslims….”

Migration of an individual from a rural to an urban environment brings about some kind of a cultural change in him. For instance, he may switch over to a new occupation, change his accent in speech, become more polished in his behaviour and so on but there is always a possibility of going back to one’s village. Secondly, one does not find himself in alien surroundings here for primarily the language, foods, clothing, festivals and so on continue to be the same in both the situations. The migration from one linguistic-cultural setting to another places an individual in alien surroundings where he has to relearn almost everything from speech to toiletry. This kind of migration gives a sort of cultural-shock to the person. When such migrations are forced upon a whole community, its very existence, the magnitude of its suffering and anguish at physical, emotional and mental levels cannot easily be assessed or analyzed. This kind of displacement brings enormous shock and suffering into the lives of the displaced. They experience Hiroshima and Nagasaki endlessly in their lives. The displaced Kashmiri Pandits have been living in exile in their own country for the last twelve years now waiting for some miracles to happen to bring joy to their lives.

The Community

On the basis of age the displaced Kashmiri community can be divided into three segment: G1- people of fifty years of age and above; G2-those between twenty-five and fifty years of age; G3-those below twenty-five years of age.

The G1 is fully aware of the linguistic-cultural moorings of the community. It speaks the Kashmiri language and observes religious rituals, rites and customs of the community. It is aware of the socio-cultural traditions, viz., festivals, ceremonies, superstitions, myths, foods and clothing and so on. It has a nostalgic longing for the valley of Kashmir and would go back if the circumstances so permit it. The migrant camps are full of these lonely, frail and skinny people. In the camps, a 12*7 feet chamber cannot house a joint family so the sons and daughters of these old people have either shifted to other chambers or migrated elsewhere in search of some kind of a semi-employment. In places far off where their sons have been able to find work, the parents find it tortuous to stay home alone for the whole day when the son is out at work. So they prefer to stay on in the camps where they have the company of other community members whom they can talk to and share their sorrows with. Thus the joint family system has completely broken down and the young children have no idea of a family with grandparents, uncles, aunts and cousins around.

The G2 is struggling to root itself somewhere. Although it loves the valley yet it is unsure whether a return there would be desirable if the situation so arises. It struggles hard to feed the family, educate the children, attend to social obligations, negotiate its existence at its new place of work or in the market and the lanes and by-lanes of the alien place(s) he finds himself in. Although he speaks Kashmiri fluently yet he has lost an interest in traditional festivals, customs and rituals etc.

The G3 is the generation of young members with little or no memories of the valley. It was of a tender age at the time of displacement and a small percentage has come to life in the plains after the displacement. (After the displacement, the fertility has come down considerably among the members of the community. Divorce rate is on the rise and one-child norm has become the holy mantra). For this segment of the displaced community Kashmir is merely a geographic entity. Their primary (vehicular) language is Hindi and English is their second language. They also have a certain degree of passive competence in Kashmiri, their gregarious language -the language of social intimacy and shared identity (Calvet,1987).

The urban-rural distinction is no longer applicable for the displaced community is scattered in several urban centers across the country with large concentrations stationed in Jammu and Delhi. On the economic scale too the community can be divided into three categories : a) The economically settled with their own houses who are in the process of integrating with the dominant cultures around them; b) the small section housed in rented accommodations; and c) the large section sheltered in the migrant camps or slums in and around Jammu. These camps, in my view, should be considered as the centers where linguistic-cultural maintenance or loss could be authentically studied.

Cultural Loss

Culture is more or less a language game as language is a repository of socio-cultural belief systems and customs of a community. Pheran and kangri have no importance in the plains so is the case with a large number of other linguistic and cultural entities which have had a socio-religious significance in the valley. The G3 is almost completely unacquainted with such terms and many more. Of such items, although large in number, a few have been recorded here for illustration.

A house in Kashmir invariably has a brànd (porch/threshold) and bràndû lívún (porch-cleaning) has a religious-cultural significance for a Hindu lady. The phrase bràmdû kåni (lit. porch-stone), land lady/wife has a cultural importance for the whole speech community. The concepts as well as their religious-cultural importance is lost to the G3. A typical Kashmiri house has three storeys: vót (ground floor), kúth (first floor) and känì (second floor). vót is used during winter for sitting as well as for cooking. kúth is the bedroom meant for use in all seasons. känì is used for cooking and sitting during summer. Two social customs i) going up to känì in spring, känì khasún, and ii) going down to live at the ground floor, vót vasún, during late autumn are no longer known to the G3. A house there would also have athòkúr kúth (prayer room), dab ‘ (wooden veranda). Panjrû (wooden netted window), bräri känì (cat’s top-floor), síngal (wooden roof), tshêy (hay roof) etc. All these terms are lost to the G3.

The onset of spring would be marked by sòntû phúlay (blossoming of flower and fruit trees). On navréh the Kashmiri ‘New Year day’ people would go to parks and gardens to enjoy the warm sunshine and the colourful spring flowers. Such celebrations have ceased to be a part of the cultural life of the community in the plains and the G3 is simply unaware of such festivities.

Walnut, almond, apricot, peach, cherry and all other fruit trees would flower in spring. The flowers would gradually turn into unripe fruit. The children as well as the adults would enjoy kernels of green walnuts and almonds. The green coat of the unripe walnut fruit would dye one’s palms dark-yellow. The vocabulary items like gól (green coat of a walnut), pìrû gùli (green walnut kernel) are not known to the G3.

Summer meant paddy and vegetable plantations and other agricultural activities associated with it. The linguistic items like thal karún (plantation) and agricultural implement like alûbäni (plough), bílchû (shovel), tóngúr(pick-axe), gìnti (pick), makh (axe) dròt (sickle) etc. are not known to the G3. Similarly, there are a number of other linguistic terms which are associated with paddy like‘dàní lònún (harvesting), chhómbún (thrashing), gandún (tying), múnún (helling) etc. which the G3 is unacquainted with.

kàngûr (fire-pot/brazier) used by every Kashmiri during winter to keep him/herself warm has several components, viz., kôndúl (earthen pot inside the Kangri, kàní (dried willow twigs), tsàlan (a wooden or metallic spatula tied to the fire pot), which are naturally lost to the G3, for kàngûr has no place in the hot plains. During autumn when trees shed their leaves, people broom those into piles, pan dúvún (broom-leaves), and put those on fire, pan zàlún (burn-leaves) to prepare tsûní (coal) for use in the Kangri. Overuse of a Kangri would burn the skin on one’s thigh which is known as nàrû tót (skin-burn). One would put a little zetû/têngúl (live coal) into tsûní kàngûr (fire pot full of wood/leaf coal) to ignite it. All these terms have lost significance, hence are lost to the G3.

phêran (a woolen gown without a front cut) has a special place in Kashmiri attire. Associated with it are the terms like pòtsh (cotton lining of a phêran), phêran làd (a fold at the bottom of a phêran), which terms are not in the repertoire of the G3. Similarly the Hindu women’s traditional head-gear,tarûngû, and its components like zùj, pùts, shìshûlàth etc. are completely lost as far as the G3 is concerned. tarûngû has an important cultural and social significance for the community especially at the time of marriage when a bride is necessarily required to wear it a day before the wedding after the religious ritual of dívgòn (the entrance of the devas).

Traditionally the community has been celebrating birthdays of the family members according to the Hindu lunar calendar. People would remember their respective dates of birth accordingly. But not now. Preparation oftåhår (yellow rice) as part of the birth day celebrations is losing ground and instead cutting a cake according to the Gregorian calendar has replaced it . Due to a lack of knowledge of the traditional calendar, the significance of the religious/auspicious days like ätham (8th day of a bright/lunar fortnight),pûním (15th day of the lunar fortnight), màvas (15th day of the dark/moonless fortnight), kàh (11th day of a fortnight) is gradually being lost. The religious festivals/ rituals like gàdû batû (fish-rice for the house-deity), kàvû pûním(crow’s purnima), manjhòrû tåhår (yellow-rice of the Magar month), hèrath salàm (2nd day of the Shiv Ratri) are least understood by the G3. The rituals like sòntû thàl (spring plate), kàvû pótúl (crow’s idol) etc. are simply lost. Same is the case with such superstitions like zangí yún (to be the first to cross some one on his/her way out of home), búth vúchhún (see somebody’s face first in the morning), sàtû nèrún (to leave a place on an auspicious day) etc. which are not known to the G3.

Shivratri has traditionally been the most important religious festival of the Pandits whose celebrations would continue for over a fortnight. Special earthen pots used to be bought on this occasion to perform pùjà of vatúkh(the bachelor shiva), kàpàlík (tantric), sóní pótúl (bridegroom shiva) and other deities for four days in succession. Each member of the family would reach home for this festival. Prasad is the form of wet walnuts and chappatismade of rice–flour used to be distributed among the neighbours and the relatives. In the plains where the family members are scattered in various parts of the country, this festival has lost the traditional importance. Now a token puja is performed with steel utensils. Similarly, the sanctity of other religious festivals like Janam Ashtami, shràvnû pûním, zèthû ätham etc. is gradually getting eroded.

The death of a family member used to be followed by several death–rites after dàh (cremation), namely, chhalún (washing), dåhím-kåhím-båhím dóh(10th –11th –12th day), pachhívàr, (15th day), màsûvàr (month-day), shadmòs(6th month), våhrûvär (death anniversary) and shràd (offerings of food and water) would be performed on these days to seek peace for the departed soul. All these rites are being abridged now to save time and money both of which are scarce with the displaced community.

Similarly, traditional foods like the preparations of lotus-stalk, potato, green vegetables, some of which, for instance, vôpal hàkh, kratsh, etc. are not even grown in the plains are not known to the G3.

The valley is a bed of flowers where a large number of them grow in the wild and a larger number is cultivated. G3 would not know what such–like names as yåmbûrzal, tènkûbatani, pìtàmbar etc. refer to. Similarly, there is a large number of terms referring to plants, birds, insects, grasses etc. which the G3 is unacquainted with.

Each language has its own resources for such social activities as greetings, condoling, blessing, cursing, abusing and so on. Kashmiri, being the mother tongue of a Hindu minority and a huge Muslim majority has a rich vocabulary of Sanskrit-Prakrit and Perso-Arabic origins, the former employed by the Hindus and the latter by the Muslims. Personal names, quite a number of surnames, names of objects which have religious connotations (like àb /pòni for water), religious terms, modes of greeting, even curses, invectives and abuses would indicate whether one were a Hindu or a Muslim (Bhat, 1997). A Kashmiri speaker would greet members of different religious beliefs (Hindus and Muslims) differently. There is a huge chunk of lexical items employed for greeting, condoling, blessing, praying etc. used by Hindu Kashmiris and an equivalent corpus used by Muslim Kashmiris. The younger generation now in the plains does not have any kind of exposure to the Muslim Kashmiri corpus. (Same should be true of the younger generation placed in the valley which does not have any idea about the Hindu Kashmiri). Thus a significant corpus of synonyms is on the verge of extinction.

Many more socio-cultural vocabulary items could be enumerated here which the G3 is unacquainted with, for instance, the terms related to such like professions/trades like carpentry, masonry or the terms employed by iron/gold smith, barber, cobbler, butcher, and so on. Similarly, such holy places like túlmúl, khrûv, shädipòr, akíngòm, shènkràchàr, parbath, màrtand etc. which have a sacred place in the hearts of the devout Hindus of the valley, do not denote anything to the G3.

Attitude

The G3 considers Kashmiri language a burden which would not benefit it in its development and progress. The homeless and bewildered G2 is concerned more about bread-earning and education of its wards. Ancestral language and culture are such issues which do not find any place of importance in its conscious mind. The issues of vital importance with it are: job, food, clothing, education, and the possibility of rooting itself somewhere – finding a permanent home for itself. It is in search of a new identity for itself for it fondly desires that the suffering and torture experienced by it due to the displacement should not be the fate of its children as well. Consequently, the G3–the innocent generation, which at this point in time is unable to appreciate the importance of a community’s linguistic and cultural identity, gets negligible linguistic and cultural input from the G2 for its social development.

G3 is deeply concerned about its individual progress. It does not see any benefit accruing from learning Kashmiri. It converses with its parents and peers in Hindi. Kashmiri is a burden it can well do without. Under these circumstances one is required to justify the use of a particular language by probably reflecting upon the inner qualities of the language, its resources, its functions and use, the religious and cultural activities associated with it and, also, the strength of the efforts made to maintain it (Lewis, 1982: 215). Language loss inevitably leads to cultural loss. Commenting on the consequences of not learning one’s own tongue, Fanon (1961) observes that such a community internalizes the norms of the other (dominant) culture ‘which leads to cultural deracination’. Consequently, its culture, institutions, life-styles and ideas get devaluated, suppressed and stagnated which may eventually lead to its integration with the larger culture around.

Linguistic Deprivation

Kashmiri is taught at the school in the Kashmir valley only. G2 does not have the requisite resources to arrange for the teaching of Kashmiri language and culture to the G3 nor is the latter interested or inclined to appreciate its parental tongue and the ancestral culture. Fishman(1990) opines that language survival depends crucially on the language(s) of primary socialization in the family. Calvet (1987) reflects on the efforts of the Shuar community of Ecuador (Latin America) which has succeeded in integrating its language and culture with education. Shuar schools are run independently of the State control. They make extensive use of radio and TV and demonstrate that the survival of a ‘gregarious language’ could be ensured through community effort.

But, unlike Shuar, Kashmiri Pandit is a community scattered in several urban centers across the country with a large number (nearly 2.5 lakh) stationed in Jammu and Delhi. Obviously, the demise of its identity as a distinct linguistic and cultural community seems inevitable within the next two generations when both the G1 & G2, the store-houses of its language and culture, would cease to be around.

Burchfield (1985: 160) has aptly remarked :

“Poverty, famine and diseases are instantly recognized as the cruelest and least excusable forms of deprivation. Linguistic (and cultural) deprivation is a less easily noticed condition but one nevertheless of great significance.”

Preservation

After the advent of Islam in the Valley, when Persian replaced Sanskrit as the language of administration, senior members of the residue-pandits (a large majority had been forced to embrace Islam) organized a kind of a conference to deliberate on and find means to preserve their religion and culture so as to prevent it from going extinct. In that historic conclave, it was decided that in order to participate in State administration, it were necessary to learn Persian, so the son’s son would learn the language of administration and the daughter’s son, if he were educated by his maternal grandparents, would learn 'bhasha ‘Sanskrit’ and religious scriptures and eventually perform religious rites and rituals. Thus, two distinct sects, one of bhasha Pandits or purohits ‘clergymen’ and another of the kaarkun ‘the men of administration’ were created. In course of time the Purohit became dependent upon the Kaarkun for dakhshinaa ‘offerings’ to make his living and the Kaarkun came to be considered as a superior class to the men of religion. This historic ‘decision’ has brought the community to an impasse now where the purohits too are scarce and the very identity of the community is at stake. At this juncture it not only involves the religious rites and rituals, customs, festivals and ceremonies, beliefs, myths and superstitions but also their mother tongue which was not under threat during the Muslim period.

The community elders need to sit together again to think about its linguistic and cultural heritage and find out means to preserve it. Otherwise, the literary and religious writings of Laleshwari, Parmanand, Zinda Koul and host of other leelaas ‘prayer songs’ would be lost for having no takers and interpreters in not so distant a future.

References

-

Achebe, C. 1975. Morning Yet on Creation Day : Essays. London : Heinemann.

-

Bhat, R.N. Honour System in Kashmiri. Indian Linguistics. Vol.58, No.1-4, 1997.

-

Burchfield ,R. 1985. The English Language. Oxford : Oxford Univ. press.

-

Calvet, L.- J. 1987. La guerre des languages et les politiques linguistiques. Paris:Payot.

-

Fanon, F. 1961. Les dames de la terre. Paris: Maspero.

-

Fishman, J.A. 1990. ‘What is reversing language shift (RLS) and how can it succeed ?’ Journal of Multicultural and Multilingual Development. 11/1 & 2:5-36.

-

Lewis, E.G. 1982 ‘Movements and agencies of language spread : Wales and the Soviet Union compared’ in R.L. Cooper (ed.) Language spread : Studies in Diffusion and social Change. Bloomington : Indiana Univ. Press.

-

Ngugi Wa Thiong’o . 1972. Homecoming : Essays on African and Carribean Literature, Culture and Politics. London : Heinemann.

-

Phillipson, R. 1992. Linguistic Imperialism. Oxford : Oxford Univ. Press.

Reference of Holy Places

by Raj Nath Bhat

The following is an extract from the Nilmata Purana (Sutra 74-181) where in mention has been made of holy rivers, mountains, lakes, etc. across the subcontinent. It also describes the drying up of Sati Lake that made it possible for human settlements to take shape in the valley of Kashmir:

The lotus-eyed Indra accompanied by Paulomi was once sporting on the bank of Sati lake. Induced by Death a Daitya-chief named Sangrha who was exceedingly difficult of being conquered, came there while Indra was sporting.

The semen of that demon who had seen Shaci, was discharged in that reservoir of water. Mad, due to being subject to passion and desirous of carrying away Shaci.

Thereafter a fight between Indra and Sangrha continued for one year. Having killed him at the end of the year, the Indra received honour from the gods and went to heaven.

A child was born in the waters out of that evil-minded Sangraha’s discharged semen which had fallen in the lake.

Due to compassion the Nagas brought up that child in the waters. As he was born in the water, so he was called Jalodbhava (water-born).

Having propitiated the god Pitamaha with penance, he obtained from him a (triple) boon, viz, immortality in the water, magical power, and unparalleled prowess.

Having obtained the power, that Daitya devoured the human beings who lived in various countries near that lake, viz; the inhabitants of Darvabhisara, Gandhara and Juhundara, the Shakas, the Khashas, the Tanganas, the Mandavas, the Madraas and the inhabitants of Antargiri and Bahirgiri.

They fled away in fear from the country and he roamed fearlessly in those desolate lands.

At this very time, the venerable sage Kashyapa travelled over the whole earth in connection with holy pilgrimage.

In this holy Bharatavarsha – he visited auspicious Pushkara, Prayaga, teeming with sacrifices and destroyer of all sins, Kurukshetra, the field of piety, Naimisha, the destroyer of sins, Hayashirsha, the holy abode of high-souled Fathers, the celestial Carankata, the remover of all sins, the holy Varaha mountain, the holy Pancanada, Kalanjana along with Gokarna, Kedara along with Mahalaya, Badhirashrama, the holy abode of Narayana, Sugandha, Shatakumbha, Kalikashrama, Shakambhari, Lalitika, Shaligrama, Prthudaka, Suvarnaksha, Rudrakoti, Prabhasa, Sagarodaka, Indramarga, Matanga-vapi, the destroyer of sins, the holy Agastyashrama, Tandulikashrama, the holy Jambumarga, the holy Varanasi, the holy goddess Ganga, daughter of Jahnu and girdle of the sky, Yamuna, the destroyer of the noose of Yama, the swift-flowing Shatadru, the Sarayu, possessed of the sacrificial posts, the goddess Sarasvati, the Godavari, the Vaitarani, the Gomati, the Bahuda, the Vedasmrti, the Asi alsog with the Varna, the Tamravarnotpalavati, the Sipra along with the Narmada, the Shona, the great river Paroshni, the Ikshumati, the Gauri, the Kampana the Tamasa, Gangasagara Sandhi and Sindhu sagarasangama.

He visited the Bhrgutunga, the Vishala, Kubjamra, the Raivataka, kushavarta at Gangadvara, Bilvaka, the mountain Nila, the holy place Kanakhala and other sacred places also.

Having heard that Kashyapa was on a religious tour, Nila-the king of the serpents – went to the sacred place Kanakhala to meet him.

Having reached there, that king of the serpents saw his father, pressed his feet and saluted him after announcing his own name.

The father smelled his forehead and honoured him in the proper manner., Then he sat on the matting made of Kusha grass.

Then the seated Naga spoke respectfully to the father Kasyapa.

‘Having heard that you – lover of Darma (piety)- are visiting the sacred places, I, with a desire to serve, have immediately approached your honour.

‘O Brahman, all the sacred places in the eastern, the southern and the western (part of the) country have been seen by you. Let us go now in the northern direction.

O honour-giver, there are holy places of pilgrimage in Madra country and on the Himalaya – the best of the mountains.

There is the auspicious Vipasha, the pacifier of sins and giver of eternal bliss, the river Devahrada, the sin-removing god Hara Haririshvara and the holy confluence near Karavirapura.

At that place the Devahrada joins the Vipasha, the best of the rivers. In the Vipasha, there is the holy Kalikasrama.

There is the holy Iravati, the destroyer of all sins. Sixty thousand sacred places dwell in single Iravati, specially in Revati (Nakshatra) and on the eighth day (of a fortnight).

There are Kumbhavasunda, the river Devika possessed of holy water, the great river Vishvamitra, the river Udda which is highly sacred and the various confluences (of the rivers). The religious merit (lies) in the Iravati and also in the Devika.

Brought down by your honour for doing favour to the Madras, it is the goddess Uma who is famous on the earth as Devika and by seeing whom a man certainly becomes purified in this world. There are Indramarga, Somatirtha, the holy Ambujana, Suvarnabindu, the auspicious abode of Hara, the sin-destroying abode of Skanda, the highly sacred lord of Uma at Rudratirtha, Durgadvara, possessed of holy water, Kotitirtha, the sacred place of Rudra, Kamakhya and Pushpanyasa. O honour-giver, (there is) Hamshapada pronounced as holy and so also Rshirupa.

In the area extending over four krosas, there is Devikatirtha at all the places where every pool is holy in all respects.

There is the sacred river Apaga and the holy Taushi which pleases the sun. There is the Candrabhaga – the best of the rivers – whose water is cool like the rays of the moon.

Vaivatitlamukha is the meritorious holy place of the Candrabhaga and so also is the sin-destroying Shankhamardala.

There are Guhyesvara, Shatamukha, Ishtikapatha, the holy Kadambesha and the area around it.

The area extending from the holy Shatamukha upto the holy place Guhyeshvara, is equal, in holiness, to Varanasi or is even higher than that.

The great river Candrabhaga is always holy everywhere but is specially so on the thirteenth of the bright half of Magha in conjunction with Pushya.

All the sacred places on the earth, including the seas and the lakes, shall go to the Candrabhaga on the thirteenth of the bright half of Magha.

Vastrapatha is stated to be holy and so also the god Chagaleshvara, the second Bhaumi and also her birth place.

The sacred place of the lake which is an incarnation of the body of Sati, is the lake Vishnupada famous Kramasara, the destroyer of all sins.’

O sage, please visit immediately these and other holy places by bathing at which, even the evil-minded human beings are freed from the sins.

Addressed thus Kashyapa whose desire had already been aroused, said “Let it be so” and went to those holy places in the company of Nila.

Having crossed the river-goddesses Yamuna and

Sarasvati, he visited Kuruksetra where Sanniti is famous.

A multitude of the holy places in called Sanniti on the earth. It is, verily, the spot to which all the tirthas including the seas and the lakes always go in the end of the dark half of the month.

He, who performs Shraddha there at the time when the sun is eclipsed by Rahu, obtains the best award of (performing) a thousand horse-sacrifices.

Having seen the Sanniti, he saw Cakratirha also about which a verse sung by Narada is current on the earth.

“Oh! the persistence of the people for the suneclipse! The religious merit obtained at Cakratirtha is ten times more than the eclipse.’

Having visited the sacred places called Cakra and Prthudaka, he saw the holy Visnupada and Amaraparpata.

Afterwards, having crossed the rivers Shatadru and Ganga, the sage reached Arjuna’s hermitage and Devasunda.

Having crossed the illustrious and sin-destroying Vipasha, Kashyapa saw the whole country desolate at that time.

Seeing the country of the Madras desolate, he spoke to the Naga, “O Nila, tell me as to why this country of the Madras has been deserted ?

This has always been charming, devoid of the calamity of famine and full of the wealth of grains!”

Nila said: “O venerable one, all this is known to you that formerly a demon-child named Jalodbhava – the son of Sangraha-was reared up by me.

Now that impudent fellow, who obtained boons from Brahma , ignores me and I am incapable of keeping him under control due to the boon of the lord of the three worlds.

By that villain of evil intellect – eater of human flesh – this whole country of the Madras has been depopulated.

O lord, the countries rendered desolate by him are mainly Darvabhisara, Gandhara, Juhundara, Antargiri, Bahirgiri and those of the Shakas, the Khashas, the Tanganas and the Mandavas. O venerable one, make up your mind to check him for the welfare of the world.”

Addressed thus Kashyapa said “Be it so” and after taking bath in the holy places all around, he came to that transparent lake in the country of Sati.

After taking a bath there, he gave up walking on foot and went to the eternal world of Brahma, merely by his own power.

He went along with Nila, the high – souled king of the Nagas. Both of them reached the abode of Brahama and made obeisance to the lotus- born god and the gods Vasudeva, Ishvara and highly intelligent Ananta, who were present there by chance.

Honoured by them, these two told the activities of Jalodbhava. Then the god Pitamaha said to this Naga-lord and the sage of unparalleled valour, “we shall go to Naubandhana to subdue him. Then the god Keshava will undoubtedly kill him.

“Having heard this, Hari, the killer of the strong enemies, went (mounted on) Tarksya.

After him went Hara, mounted on the bull, along with his wife. Brahma went mounted on the swan and the two Nagas mounted on the cloud.

Kashyapa went by his supernatural power. Indra heard that and, in the company of the hosts of gods, went to that place where Keshava had gone.

Yama, Agni, Varuna, Vayu, Kubera, Nirrti, Adityas, Vasus, Rudras, Vishvedevas and the hosts of Maruts; Ashvins, Bhrgus, Sadhyas, the sons of Angiras, the illustrious sages, Gandharvas, the hosts of heavenly maidens; all the wives of the gods, the mothers of the gods, the hosts of Vidyadharas, Yakshas seas and rivers (all went there).

Ganga went mounted on crocodile, Yamuna on tortoise, Shatadru on bull and Sarasvati on buffalo.

Vipasha went mounted on horse, Iravati on elephant, Candrabhaga on lion and Sindhu on tiger.

Devika went mounted on wild ox, Sarayu on deer, Mandakini on man and Payoshni on goat.

Narmada mounted on peacock, Gomati on Saranga deer, Godavari on sheep and Kampana on swan.

Gandaki went mounted on hecrane, Kaveri on camel, the holy Ikshumati on crocodile and the holy Sita on shecrane.

Lauhitya went mounted on Camara deer, Vankshu-the fast going one – on Kroda (hog), Hladini on partridge and Hradini on rooster.

Pavani went mounted on a horse, Shona on a serpent, Krshnaveni on cloud and Bhuvena on hare.

These and other rivers also went mounted on their respective mounts. All these, with a desire to see fight, followed the lord of the world.

Having reached Naubandhana, Keshava, verily, took a firm stand.

Hearing the sound of the retinue of the gods, the evil-minded demon, knowing himself to be imperishable in the water, did not come out.

Having come to know that he would not come out, the pleased Madhusudana entered.

Naubandhana, in the company of the gods.

Rudra stood on Naubandhana peak, Hari on the Southern peak, Brahma on the Northern peak and the gods and the Asuras followed them.

Thus, they entered the mountain. Then the pious minded god Janardana, with a view to kill the demon, said to Ananta:

“Breaking forth Himalaya today with the plough, make soon this lake devoid of water.”

Then Ananta, resembling a mountain and possessed of lustre equal to that of the full moon, expanded himself, covering the earth and the heaven and terrifying the hosts of demons all around.

Dressed in blue, wearing diadem fastened with gold, worshipped by all the gods, he broke forth Himalaya, the best of the mountains on earth, with plough.

When the king of the best mountains had been broken, the water flowed forth hurriedly with force, terrifying all the beings with its violent rush and sound and overflowing the tops of the mountains with curved waves like Himalaya touching the sky.

When the water of the lake was disappearing. water-born practised magic. He created darkness all around and the world became quite invisible.

Then the god Siva held the sun and the moon in his two hands. In a twinkling of the eye, the world was brought to light and all the darkness had vanished. Unfathomable Hari, assuming another body with the power of Yoga, fought with the demon and witnessed that fight through a different body.

There was a terrible fight between Visnu and the demon, with trees and peaks of mountains. Hari cut off, forcibly, the head of the demon and then Brahma obtained gratification.

*Source: Nilamata Purana by Dr. Ved Kumari

Cosmic Design: My Destiny

by Raj Nath Bhat

The Childhood memories

It was a sunny Sunday morning. My mother Dulari woke me up. My father Jagan resented. Being the eldest among siblings, I was supposed to learn good manners. The sun was up in the sky - a pleasant, breezy morning. I came down the stairs into the compound, thence to the river bank that flows behind our house. Crystal-clear, shallow river water invited me in. I rushed back home, got my towel and innerwear and had a bath. This pleased my mother. My siblings, three in all, got up and followed me to the river. I did not allow them to bathe. They washed and went back. Together we had salt-added-tea and phulka. I was asked to follow cows and calves up to the big river bank where the cowherd would tend them till dusk. I did the job. I was the last boy from the village following our cattle. The job irritated me every morning because despite owning cows there was no milk at home. On occasions I or my younger brother R would go to the milk man’s house to fetch milk or curd. The tradition of owning cows (Kamadhenu) and considering it a sign of affluence (gavdhana) stuck with us.

Kids used to be beaten up frequently in the villages and kids readily invite elders’ wrath. Being the eldest I used to beat up my siblings for any or none of their errors! I remember distinctly hitting R who ran after me in the village lane when I had returned home after over a week from my high school town where I stayed with my maternal great grand parents. I was wearing a steel bangle, a novel acquisition from the town- that hurt R. He rushed back home crying. On another occasion I beat up our sister D, who was hardly three years old, so mercilessly that I felt that her bones could break. She was too tiny and delicate. I do no remember why I did that. I cannot recollect any such incident with regard to K, the youngest brother, who suffered a polio-attack at three years which scar continues with him.

It was a monotonous life style that showed little change of pattern, if any. Morning one had to follow cattle to the big-river bank; back home it was a simple breakfast, then food- rice with knolkhol, school and back. Evening one would play or help family elders in the kitchen garden. It was real fun during summer months in the kitchen garden where we grew vegetables, especially knolkhol, beans, cucumber, spinach, green chilies, for family consumption. Our father used to make gardening interesting by fetching new spades and other iron implements that interested and motivated kids to do gardening. We would compete with one another with the size of plod that one raised. Our father was a lover of flowers. He had planted a large variety of flowers that would flower in different seasons, March to November. Our garden had the distinction of growing wild yellow ‘pitambar; during summer months that flowers at sunset and withers at sunrise. We used to observe and enjoypitambar sprouting in the evening. Kids from some other families (if allowed by their parents) used to join us in the fun.

Kids of the families that tilled their farming lands had little time to do other chores. They used to be busy with their family elders in the paddy/mustard fields. The village had a mixed population of Hindus and Muslims.Hindus were in a miniscule minority. Hindus worshipped at the Bhuteshwar temple every morning as well as in the evening. There was an idol of Kali that disappeared suddenly in 1986 whenKashmir was brewing inside. There was a thousand-faced Shiva temple a KM away from our village that was blasted off in the nineties. Muslims offered namaz, five times a day, in the village mosque. Both the shrines are located at stream banks.

Bhuteshwar - a Shiva temple - is located across the little stream that flows at the back of a few Hindu houses including ours. Most of the Hindu houses as well as the temple faced west whereas Muslim houses faced west or south. No house faces north. Three Hindu women, including my mother, used to compete with one another to reach the Bhuteshwar temple in the early morning hours. Not many people in the village knew about it. My father, his cousin brother Radha, and Sham were the only men who worshipped Bhuteshwar regularly. Sham is the only person who worships at the temple now. I visited Kashmir in 2008 summer, nineteen years after our displacement and my travelogue has appeared in a community e-journal ‘Har’van’ edited by MK Raina from Mumbai and also in the community magazine ‘Naad’ published from Delhi.

Winters are harsh. Elders as well as kids used to confine to the ground floor, adjacent to kitchen, wearing a long and broad woolen ‘pheran’ with a kangri(brazier) underneath. Since most houses had roofs of hay, expert youth used to remove the snow from the roofs with an oar-like wooden pole. This would fill the compound and the house-eaves with meters-high snow. Kids or elders used to remove snow with spades to make walk-able space from the house porch to the stream. Winters with little snow-falls used to be a matter of joy for kids because it gave them ample space and time to play. The village kids played cricket, Kabbadi and some rural games.

My eldest maternal uncle informed me that he used to go to Anand’s house even as a child because his maternal aunt Sondar was married to Anand’s second son, Ganesh. It was a huge household where a large number of children would assemble to have food- rice with knolkhol; one could hardly see who all ate in the evening under the traditional wood-light- a special burning wood used to be hung on the wall to provide light to the whole ‘hall’! Electricity reached the village in 1970-71.

During spring, Hindus shifted kitchen to the second floor that was quite airy. Mosquitoes (non-malarial) would invade during summer months that were warded off by burning cakes of dried cow-dung whose smoke brought tears to one’s eyes. Kids enjoyed this kind of ‘crying’. The bed-rooms were located at the first floor. The Muslims preferred constructing two floored houses. Their kitchens were on the 1st floor; the ground floor had bed-rooms. Things have changed now.

My paternal grandfather Anand was a pious Brahmin well read in the Veda-s and Purana-s. He used to perform an annual yagya where devotees from far and wide in the area used to join to seek Goddess’s benedictions. He expired at the age of 100, nearly a year prior to my birth. His wife died fifteen days later. And Sona’s wife (Sona was Anand’s younger brother) followed a month after. My father Jagan was Anand’s youngest son (5th) who had been given in adoption to his widowed paternal aunt Sati. She had lost her husband, Maheshwar, at a very young age.He was in the postal department who drowned in south Kashmir nearly 20 kilometers away from our village. His dead body was brought to the village at mid-night. His young widow lost consciousness and had to suffer rude treatment for nearly a decade whenever she fainted.

There perhaps was no provision of pension for the family of the deceased then. The young widow lived on what her dead husband’s brothers’ families offered her. She also had her share of land etc. that enabled her to live comfortably. After adopting my father, she became livelier. She along with her brothers became the disciple of a spiritual Guru at Durganag, Srinagar. Her brothers had been poor shop-owners and the last Hindu family in a locality at Kadipora, Anantnag, They were so badly harassed that they migrated to a tiny village near then unknown Pahalgam. My grandmother died some six months after my birth. She used to take little-me in her lap and feed sparrows and other birds with uncooked-rice at the window during the whole winter. My birth had pleased her a great deal. Since I was born less than a year after Anand’s demise, my father and several others in the extended family considered me as Anand’s rebirth.