Shyam Kaul

The author is a veteran journalist, based in Jammu.

Articles

Tara and The Dilemma Of Kashmir

By Shyam Kaul

The imam at the principal mosque at Safapur was concluding his address when a man walked in, went up to him and whispered something in his ear.

A shadow of grief fell over the imam's face. He turned to the congregation and broke the news of a death in the village. "You will be sorry to learn", he said, "of the death of Tarawati, Mokdambai (headwoman) of Kolpur, a little while ago. As there is no Pandit now here in the village, I call upon you to proceed to Kolpur, after offering your prayers, and arrange the last rites of the deceased in an appropriate manner".

It was early 1990, the heady days of the freshly-arrived cult of terrorist violence in Kashmir. The boom of guns, bomb blasts, grenade attacks and shootouts, had heralded the arrival of the new cult. Gun-wielding "mujahids" had appeared from nowhere, getting into the headlines straightaway. The attention of the whole world got focussed on them after they organised an unprecedented operation, the abduction of the daughter of the then Home Minister of India, Mufti Mohammed Sayed. This sent the entire population of Srinagar city into frenzied excitement by creating delusions of "Azadi", which, at that moment, appeared to be just round the corner.

Against the run of this torrent of all-pervading euphoria, the minuscule Pandit community was gripped by fear and panic, for the "mujahids" had practically launched their "liberation" struggle by selective killings of Pandits, beginning with a BJP leader, TL Taploo, a retired judge, NK Ganjoo and many others. They made it appear that the Jehad was not only against India, the very name of which became a malediction, but also against Pandits, who were inevitably identified with India, it was then that Pandits started fleeing the Valley. The wave of panic swept across the villages and hit Safapur with a powerful blast that damaged the house of Kauls, a well-known Pandit family of the paragana. In a couple of days the entire Pandit population of Safapur, not exceeding fifty souls, was on its way to Jammu, via Srinagar. Tarawati, the widowed headwoman of Kolpur, which formed part of the larger Safapur village, her son and daughter-in-law, were among these fleeing Pandits.

On reaching Srinagar, Tarawati's son left her and his wife behind, and proceeded to Delhi to explore whether he and his family could find shelter there, instead of any other place outside Kashmir.

Tarawati had been in Srinagar hardly for three days when homesickness started tormenting her. Then one morning she took a bus for Safapur, telling her daughter-in-law, that she would be back when her son returned from Delhi.

At that time Tarawati could not have imagined that those were the final hours of her life and that fate was drawing her to Safapur, perhaps only because of her life-long bonds with the soil and the people of her village, on the banks of picturesque Manasabal Lake.

Back at her home, Tarawati found a new life vibrating inside her, but she also found something ominous in the village ambience. It was taut with fear and tension, and spontaneity in people's behaviour was missing. This however did not prevent the old lady from mixing and mingling with her Muslim fellow villagers as she had always done before. But the joy of reunion was short-lived and only after three days she had a stroke and died peacefully in her home, with her neighbours by her side.

The prayers over, a large section of the congregation at the mosque, hurriedly made its way to Kolpur. By then, a large crowd, including women, had assembled at the headwoman's house. The village women took care of the last rites of the deceased, before menfolk carried the body to the cremation ghat at the banks of the lake. Some elderly villagers, who were fairly conversant with Pandit customs and rituals, helped cremate the octogenarian headwoman properly, as a large gathering stood by reverentially, praying for peace to the soul of the departed.

Tarawati had come to Safapur as a 13-year old bride, married into the nambardar family of Kolpur, and had spent all the 72 years of the rest of her life in the village, going out only occasionally. She would sometimes go to Srinagar, to attend some function of her relatives, or to her ancestral village, 20 kilometres away. She had once been to Jaipur where her son had served with the army.

Widowed at the young age of 40, Tarawati had not only brought up and educated her children, but had also discharged her functions with utmost responsibility as headwoman. Over the years, she had acquired a protective, motherly image, loved and respected by all.

In the evenings, during summers, flocks of children would come to play in the sprawling compound of Tarawati' house, under the shade of the big chinar tree that stood at the gate of the compound. She would call the chinar her mother-in-law, because, as she put it, "when I came here as a young bride, it was this chinar which greeted me before I stepped into my new home. Since then it has been an inseparable friend and a part of my life. I have rested under its balmy shade and watched and enjoyed children playing under it as mellifluous birds sang in its thick branches".

In her more ruminative moments Tarawati would recall, with traces of old grief in her eyes, how she had spent her lonely evenings, after the death of her husband, sitting against the supportive trunk of the chinar, and shedding silent tears.

To the frolicsome and noisy children, Tarawati had always something to offer by way of small eatables like a walnut, a pear, smoked corn, or whatever she found in the house. She also had always something to give to the small children of poor fishermen, who lived a little distance away on the fringes of the lake. They would often come in the mornings, asking for something to eat and she would never disappoint them. In fact every night she saw to it that some food was left over for the fishermen kids next morning. Some of these children would be so small that they could not even call out 'Tara' the fond name given to her by the villagers. They would call Tala or Taya.

Her older neighbours and other villagers were her frequent visitors too. They came to seek her advice, guidance and help in resolving disputes pertaining to lands, marriages and inheritances. She went all the way out to share their joys and sorrows.

Tarawati was an illiterate woman, but her close affinity with her fellow villagers and her deep understanding of their day to day problems, had made her into an institution, to which they always looked in their moments of distress and difficulty. Every villager mourned her death. Her departure created a feeling of emptiness that no one in her neighbourhood could easily reconcile with.

But those were the days of rapid changes in Kashmir. Militancy had gained phenomenal immensity and taken control of everything, including the lives of common people in cities and villages, who could not even talk and act as they would normally do. In fact when a woman neighbour of Tarawati wailed loudly over her friend's death, a gun-toting youth from a neighbouring village, walked into her home next morning and scolded her for shedding tears for a "Kafir".

The nineties in Kashmir, perhaps, marked the saddest era in the post-independence history of this ancient land of sages and rishis, known for its traditions of peace, amity, non-violence and tolerance. It witnessed not only the displacement and exodus of tens of thousands of people like Tarawati, but also the annihilation of the noble civilisational heritage they represented.

After Tarawati's departure, it was not long before her "mother-in-law" chinar fell to the axes of money-hungry militants. One morning a group of them came, followed by a team of axemen who immediately got down to their job. It took them several days to bring down the whole tree, limb by limb and branch by branch. It was sold right there, partly as timber and partly as firewood, fetching a fat price for its destroyers. It was not the only chinar that met this fate as gun culture thrived in Kashmir. Hundreds of chinars all over Kashmir, as also other trees in government plantations and forests, were felled in similar fashion for satisfying the greed of "liberators" of Kashmir, drunken with the power of newly-acquired guns.

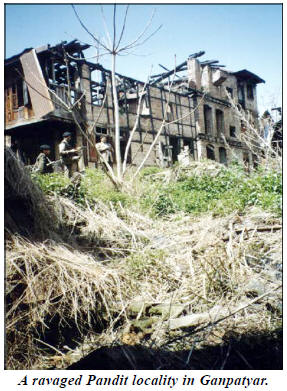

It was also not long before the three-storey house of Tarawati was set ablaze and reduced to a mass of rubble. None of her neighbours came out to make an effort to put out the blaze. Perhaps not because they would not want to do so, but because times had changed. The writ of the gun-wielding insurgents ran supreme, and arson formed a part of their agenda which no one could defy. Those who had dared, though rarely, had paid a heavy price. Hundreds of Pandit houses, government buildings and schools went up in flames that way.

Some years later, in 1997, a grand nephew of Tarawati, who had also lived in Safapur and owned property there, visited his village. His house had once stood next to his grand aunt's. He found village dogs snoozing on the wreckage of Pandit houses, including Tarawati's imposing house of Maharaji bricks and deodar. The boundary walls of the large compound had disappeared. No children played there. Instead it had become a grazing ground for village cattle.

The gentleman who, as a boy and later as a youngman, had been a witness to the busy comings and goings in the headwoman's house, wondered whether the place where dogs lolled now, was the same where she had once spoken words of advice, counsel and comfort to her Muslim fellow villagers.

He could not exactly locate the spot where Tara's great chinar had once stood, in all its glory and grace, rising high into the sky. The place had been levelled into a barren patch.

When he came back from Safapur, all he got with him, as evidence of what once was a thriving Pandit locality, presided over by a grand old lady, were pictures of some obscure ruins that once had a name. He told his friends in Jammu that standing there, all by himself, and trying to paper into his past that lay at his feet in the shape of burnt bricks and charred wood, he felt like crying. But there were not tears in his eyes, for the tragedy was beyond all tears. Or perhaps the ever-blazing fire, from guns that never fell silent, that had engulfed his homeland, had also burnt up all his tears. Just as the ruins of Tara's properties had reduced to ashes also her identity and her presence in Kashmir's historical, cultural and social mosaic.

Tarawati is no more. Her children and grandchildren live in exile. Their identity in Kashmir is erased for all practical purposes. But in the new description of Kashmir, that has emerged after the rise of terrorist violence, who now is the real Kashmiri ' The one who raced from a mosque to a cremation ghat to ensure that a Panditani got a decent and dignified funeral' Or the one who later set her house on fire and felled her chinar, only to destroy her roots and wipe out her identity as a true Kashmiri' That precisely is the dilemma of Kashmir.

The diaspora of the children of Tara, and those of thousands of other Kashmiris like her, notwithstanding, the dilemma remains. And as long as it is there, Kashmir will continue to bleed.

Kashmiri Pandit has been the worst victim of this dilemma. The zealots of "azadi" refuse to see and accept him as a Kashmiri, before anything else. For them he is a symbol of India, an eyesore of Indian presence in Kashmir and therefore something to be got rid of. That has been the way of all zealots all over the world.

But destruction of symbols never destroys what they represent and stand for. If it were so, then this world would be bereft of many civilisations and cultures, and many religious beliefs and political ideologies.

During the course of its history, Kashmir has suffered too due to the baneful medieval peculiarity of destruction of symbols. Even now this outdated curse is being revived here and there, as happened in Kashmir, where the militants went after many symbols in a bid to destroy the entire past of the Valley. From the witch-hunt of Pandits and nationalist Muslims, to the siege of Hazratbal and the burning down of Chrar Sharif, there is a chain of instances of calculated attacks on the symbols of Kashmir and Kashmiriyat. The design behind these pre-meditated attacks, obviously, was to obliterate Kashmir's heritage of noble values based on human brotherhood, peace and non-violence, and foist on it an alien culture of violence, narrow-mindedness and religious fanaticism.

Perhaps that is the true concept of "azadi" which the zealots in Jammu and Kashmir have envisaged. The dilemma persists. Today the Kashmiri is a case of split personality, torn between religion, politics, regional aspirations, parochial complexes, sectarian loyalties, accession, de-accession, azadi, autonomy, India, Pakistan, et al. The muddle has been made worse by exploitative external interventions.

The Kashmiri has lost his way in the maze of India's mishandling of situations, Pakistan's instigations and phoney promises, dangling carrot of UN resolutions, machinations of self-serving politicians, and interference of foreign powers and other busybodies. All this has made him into a political schizophrenic. Time has now come for him to cure himself, rediscover himself and then judiciously choose and mark out his future course of action.

He has to decide whether he will remain a Kashmiri, true to his responsibility, his land of birth and his cultural heritage, or whether he will surrender to the zealot who has intruded into his personality and his individual and collective psyche.

Today's Kashmiri has to look back, as well as, ahead of him, to ensure that he is not wrenched away from his moorings, and also, that he is prepared to go along with forward-looking, universal and progressive visions of the twenty first century.

Unless the Kashmiri does that, he will continue to be bedevilled by dilemmas.

A cry in wilderness

By Shyam Kaul

AS one of the hundreds of thousands of displaced Kashmiri Pandits, the past for me is not merely the “ old, unhappy, far off things, and battles long ago.” It is a reality which lives with me, and which in many essential respects, is a prolongation of the past. It is a gnawing pain in the soul, that comes more agonizingly alive when one comes across things written down years ago, like the letter that appeared in Kashmir Times, way back on October 30, 1997.

The letter, written by late Tariq Abdullah, son of the redoutable leader of Jammu and Kashmir, Sheikh Abdullah, and younger brother of Dr Farooq Abdullah, who happened to be the chief minister of the state in 1997, is reproduced here verbatim:

“Dear Editor, A veritable racket is going on in Srinagar in regard to houses belonging to the migrant Kashmiri Pandit community. An instance in point is about the House No 414 at Jawahar Nagar, belonging to Ramesh Kaul, who is a migrant. Last month the house was forcibly occupied by some locals who threw out the lawful tenants residing in the house. The matter was referred to the DG of Police, the state minister for Home, the revenue Minister and the DIG Range. However nothing was done to restore the house to its owner. Upon painstaking inquiry it was found that the house was occupied under the patronage and protection of the local SHO of the Raj Bagh police station. Furthermore, it was found that money changes hands from the illegal occupiers to the protectionist racketeers. On behalf of the hapless owner I wrote to the above named persons but a deaf ear was turned by them. I have now written to the state Governor.

“It is great shame that while on the one hand the government is committed to restoring forcibly occupied migrant property to the migrants, yet, on the other, protectionists’ racket in migrant properties is going on under the patronage of authorities and nobody is doing anything about it. It becomes pertinent to ask here as to how it is expected of the migrant Kashmiri Pandit community to return to the Valley if their very homes are illegally occupied under the protection and patronage of the authorities? It is time this racket was exposed and forcibly occupied houses restored to the owners. Only then can the migrant community hope to return to the valley. Tariq Abdullah, Gupkar Road, Srinagar.”

The letter is a quintessential essence of what happened to Pandit properties in Kashmir between 1990 and 1996, when terror ran berserk in Kashmir. The letter could also be described as a prophetic piece of writing about what has been happening to such properties from 1996 onwards, till date, when democratically elected governments are in power. The subject matter of Tariq Abdullah’s letter is equally true today, but, of course, in larger, starker and more distressing dimensions. There are thousands of Ramesh Kauls, running from pillar to post today, to reclaim their lawfully owned houses, lands, orchards, and religious properties, illegally occupied by land and property grabbers, with the “protection and patronage of authorities”, but they do not find redressal anywhere.

In a democratic setup, it is normally expected of the representtive governments that they shall be answerable and accountable to the people they represent and rule over. Kashmiri Pandits, driven out of their land of ancestors by oppressive and intolerant circumstances and living now in exile, are the largest religious minority of Kashmir. As such and as citizens of this state, it is their fundamental and inviolable right to demand the protection of their properties and also its restoration to rightful owners. Normally any representative, responsible, accountable and conscientious government would have, on its own, honoured the right of the displaced community and acted accordingly. But the successive governments in this state have miserably failed to do so, more out of calculated unconcern and unresponsiveness, than innate incompetence.

Both, prime minister, Dr Manmohan Singh, and chief minister, Ghulam Nabi Azad, are on record having assured the Pandit community that measures, like building of some lodgings in Jammu, were make shift arrangements, and the ultimate objective was to create conditions for return of displaced Pandits to their homes in Kashmir.

But to quote, Tariq Abdullah’s eleven year old letter, “ It become pertinent to ask here as to how is it expected of the migrant Kashmiri Pandit community to return to the valley if their very homes (and to add, their other properties) are illegally occupied under the protection and patronage of the authorities?”

Go to any part of Kashmir today where Pandits used to live and you will come across scores of instances of forced occupations of their houses, agricultural lands, orchards, religious places and properties. The successive governments of the state have never even as much as moved their little finger to correct and undo this criminal defiance and violation of the law of the land. Some assurances given by the government in this regard have always turned out to be half-hearted and ineffective, obviously due to the lack of will, initiative and determination on the part of the people at the helm of the government.

There could be no better instance of the government’s lackadaisical attitude regarding important issues concerning the displaced community than the one about the urgency of the enactment of legislation for the protection of the religious properties of Hindus in Kashmir. A bill in this regard has long been pending before the state legislature, but the government appears to have chosen, seemingly by design, to drag its feet on the issue. Meanwhile the Hindu religious properties in the valley are increasingly becoming a happy hunting ground for property racketeers and professional land grabbers, like some characters of doubtful credentials, masquerading as religious figures.

Sometimes we hear much talk of the return of Pandits to Kashmir, and the refrain always is that “ Kashmir is incomplete without Kashmiri Pandits.” Almost all separatist leaders are now joining in the chorus too. But we have yet to hear anything from these leaders, both mainstream and separatist, by way of elaboration of how to convert the “incomplete” into “complete”. We have long been waiting for this elaboration, which would indeed be like music to our ears, and would perhaps help in paving way for the reclamation of our grabbed homes and properties, and for our return journey to our homes. Please come out with it.

Many years back, Khushwant Singh wrote in his highly popular column, With Malice Towards One and All: “Not many of us are aware of the plight of Kashmiri Pandits who have fled from the Valley for fear of their lives, leaving their homes and properties behind them. People who talk glibly of Kashmiris secular traditions turn a blind eye to the travails these refugees are undergoing for no other reason than that they are Hindus. They callously dismiss it as false progaganda or ‘playing the Pandit card’. They should meet some of them now living in Jammu and Delhi to have their visions corrected.”

Yes, many still are not “aware of the plight of Kashmiri Pandits who have fled from the valley for fear of their lives.....” Among them, perceivably, are also the governments at the Centre and here in Jammu and Kashmir. And this is no overstatement.

Temple that vanished

By Shyam Kaul

If someone were to look deeply into the eventful, though disconcerting, developments of the past twenty years in Kashmir, purely from a mundane angle of ‘profit and loss’, it would make an interesting study and a revealing one too.

Even for an average Kashmiri who has been through and suffered or benefited, from these developments, there is enough to recollect by way of his experiences, far more painful than comforting.

The rise of militancy and violence in the early 1990s which had instantly planted the dreams of ‘azadi’ in the eyes of the people is a thing of the past. The dream has so far been and still continues to be in doldrums, with hardly any hope of its realization in its original or modified forms in the foreseeable or distant future. This could be counted as the major loss for the protagonists of ‘azadi’.

On the ‘profit’ side, however, the picture is not bleak at all. In fact it is very rosy for large sections of Kashmiri society. Haven’t we seen, during these past two decades, the emergence of lakhpatis and crorepatis in plenty, with many arabpatis in the making? The gun has liberally sprayed its blessings through bullets on all those who used it, not for the ‘liberation struggle’, but for their pelf and power, prosperity, pleasures and a merrier life. The power of gun has created a neo-rich class in Kashmir whose affluence has been manifesting itself in many ways, including a spectacular spate of building activity, especially in urban areas.

We now have an affluent class of politicians too, many of them masters of millions. How and why, need no answer because what is visible to the naked eye is self-explanatory. After all the paradise on earth is now also the receptacle of lucre from sources galore. No wonder the perpetuation of militancy and uncertainty has become a vested interest with many sections of our society.

We Kashmiris have a weird knack of turning crisis situations, such as natural calamities like floods, earthquakes, droughts and of course man-made militancy, into opportunities for making a fast buck the easy way. Over the past twenty years, the smarter among us have fully put their knack into use to freely fish in troubled waters of Kashmir. Their ‘achievements’ are there for anyone to see and that is why they want the troubled waters to be always in high tide.

When talking of ‘profit and loss’ to the fellow displaced Kashmiri Pandits (KP) in Jammu or elsewhere in the country, one often comes across pithy and expressive comments like, for instance, ‘India may or may not lose Kashmir, but the KP has lost it.’

Judging by the sufferings of the KP community, beginning with their displacement and exodus, there appears to be quite some truth in their fears. Having left the valley, they instantly lost their habitat, their social, cultural and pluralistic milieu, their centuries-old roots of belongingness to their land of ancestors and their fundamental right of living freely and honourably in their own homes in own land of birth. Meanwhile during the endless years of their exile, the KPs have lost almost everything they had left behind, except the throwaway returns some of them got for parting with their properties. These deals are now acknowledged as ‘distress sales’ and efforts are being made to get their annualled by the government.

Lately the most talked about ‘loss’ is that of religious shrines and the landed properties of these shrines. The situation indeed is worrying as reports of large scale encroachments, illegal occupations and clandestine, unauthorised and illegal sales, continues to pour in. The situation is further aggravated by the government’s inability or more aptly, apathy is correcting and preventing the widely practised wrongs. There is a bill before the state legislature now for the protection of the religious properties of Kashmiri Hindus awaiting its enactment as a law. But the government appears to be doing calculated heel-dragging in the matter.

As if to certify the veracity of the disturbing situation about religious properties, my journalist colleague and fellow Safapurwala, Ashok Pehelwan, asked me one day recently, in an asitated voice, “Could you believe that a plot of land, with a temple standing in its midst, has disappeared?”

”No, I can’t,” I shot back, “how can it happen? No doubt we hear of encroachments, forced occupation, vandalisation and the like, but how could there be a disappearance?”

Safapur is a largely-spread village, on the banks of Mansbal lake, with Kolpur as one of its extended localities, a mini village by itself.

In early 1980s, Tarawati, the redoubtable and popular Mokdambai (headwoman) of Kolpur, took the initiative for building a temple in the village. The search for a piece of land started in right earnest with the spontaneous cooperation of Muslim members of the village community. Finally it was decided that the government would be approached for a plot of land on the lakeside of Kolpur. Accordingly a mixed delegation, headed by Tarawati, met the revenue authorities at the then tehsil headquarters at Sumbal. The revenue officials were deeply moved by the enthusiasm of the mixed delegation and the tehsildar sanctioned a plot measuring nearly two kanals of land for building a temple.

Again, with the collective efforts of the villagers, it did not take long for the temple to come up. Yet again the youths of the village joined hands to retrieve an imposing and tall lingam of Lord Shiva transported it to Kolpur and installed it in the temple. The lingam had been pushed into the river Jhelum by marauding tribal invaders from Pakistan, in 1947, at village Asham, four kilometres away from Safapur, after removing it from a place of worship of Rajput Dogra orchardists in the village.

Ashok Pehelwan told me that a few weeks back two Muslim neighbour from Kolpur had come to Jammu and they informed him that a fire brigade station was coming up close to the temple, which was in a bad shape, with its boundary wall having completely collapsed, and the temple partly vandalised. They also urged him to ensure that, to beging with, the boundary wall of the temple is reconstructed so as to protect the temple area from any encroachment. The internal repairs, the two men suggested, could follow later.

Ashok acted promptly, got in touch with fellow KPs of Kolpur Safapur, now living at different places. They raised funds for the repairs at the temple and decided to start work without any delay.

The next step naturally was to get the details of the land area of the temple from the concerned revenue authorities. It was then that the disappearing trick came to light. The concerned Patwari of the area informed them that in the revenue records nothing like a temple or any land under it existed, and therefore he could not provide them with any details, for a non-existent structure.

Where have the temple and its land disappeared, inspite of standing where they are? They do not exist simply because the revenue records are sacrosanct, and therefore no temple nor its land exist at Kolpur. Now go and find the answer for yourself.

Chimp, Hangul And Person

By Shyam Kaul

In Vienna there is a 26-year old chimpanzee, named Hiasl. He is fond of eating pastry, enjoys watching TV, and his faourite pastime is painting. But he abhors coffee.

Hiasl's lovers and other animal rights advocates are now busy waging a legal battle to get the chimp legally recognised as a "person". If they succeed, it would entitle Hiasl to get donations for his food and upkeep, as the monthly expenditure on this account runs into thousands of dollars. Under the Austrian Law, only the status of a "person" could give Hiasl a legal entity and enable him to hire a paid guardian to taking care of his upkeep and other needs. It would also qualify him for the right to own property.

Here in Kashmir, we are having, more or less, a similar situation. But in this case it is not an "animal" that is seeking to get the status and rights of a "person". It is actually someone who is already a "person", but is being denied his natural and fundamental rights as a "person". It is the exiled Kashmiri Pandit (KP), who, inspite of being a "person" of the status of a hereditary citizen of Jammu and Kashmir, is for the past two decades, languishing in homelessness and running from pillar to post to establish his inherent right to live in his own home, in his own land of ancestors, as a free citizen, without fear or danger to his life and property.

Kashmir, it is relevant to mention here, is also the exclusive habitat of the majestic stag, called Hangul or Hangal, which is among the endangered animal species, and has been for a long time, struggling between survival and extinction. It is an interesting coincidence that among the Pandits of Kashmir, Hangul of Hangal is a surname. No doubt, it is limited only to a small number of families, but going by the turmoil, violence, terror and killings of past two decades, with all the diastrous consequences, especially for the KP community, it would be apt to apply the surname Hangal to the entire endangered human species of Kashmiri Pandits.

Today in the din of happenings like Round Table Conference (more curved than round), internal dialogue (less dialogue, more cuss words), peace process (more ballyhoo, less process), safar-e-Azadi (Safar sans azadi) and the deafening tumult about self-rule, joint management, troop reduction, demilitarisation, human rights violations, and what have you, nobody has time, nor inclination to listen to the voice of the displaced Pandit, who, undoubtedly is among the worst victims, if not the worst, of the twodecade old scourge of militancy and terrorist violence. Nobody has any answers to his questions, his demands, and his problems, and to the ultimate question of his return to his land of birth, and rehabilitation in honour and dignity.

Winston Churchill said once that, "There are a lot of lies going around..... and half of them are true." All that the Pandits in exile have been hearing, coming from the government during the past 18 years, are lies, but let alone "half of them", not even one tenth have come true.

What, for instance happened of the lie that the successive governments over the past 18 years have been feeding the KPs with that their return and rehabilitation in Kashmir was a "top priority" of the government? Or the lie about the government having ordered, several years ago, a survey of the KP properties, lands and other assets in Kashmir, with a view to preparing a detailed inventory for the benefit of the concerned community as well as the government? Or the lie about district commissioners having been asked to expedite the district-wise survey and compile the inventory at the earliest possible? Or the lie about the assurance of the government that all encroachments, forced takeovers and illegal occupations of KP houses, lands, orchards and other properties would be ended forthwith and the properties would be restored to lawful owners? Or the lie that the government had plans to assume supervision of all Pandit properties, back in Kashmir, in order to save these from falling into the hands of illegal grabbers? Or the lie about the government's "determination" to stop vandalisation, encroachment and occupation of KP temples, shrines and other religious properties in the Valley? Or the lie about taking "stern action" against the illegal sales of Kp religious properties, by some individuals, including non-state subject persons, who were not authorised by anyone to do so? Or the lie about opening up new avenues of employment to thousands of jobless KP youths, including those living in the Valley? It is interesting, and perhaps not for nothing, that Chief minister, Gulam Nabi Azad, unlike his predecessors and preceding governments in power, is maintaining a studied silence on the issue of KPs return to Kashmir? He appears to be acting on a popular Kashmiri saying; "Silence is silver; when observed, it is gold." Or is it a hint, an indication, of Delhi and Srinagar having finally wrapped the ribbon round the issue of the return of KPs to Kashmir and locked it up for all time? If, however, it is a lie too, then all that we can do is to hope that this one will not come true, either.

History tells us of the obliteration of people, groups, and communities, at different times, but the one that the KPs in perpetual displacement are faced with is unique. No doubt it started with the onslaught of the alien cult of terror and violence, dyed in religious fundamentalism, but the process is being systematically completed by our own secular, democratic and representative government. It is a clear instance of pushing a whole community, by no account obscure or unknown into disappearence from its own land of inheritance, before consigning it to the oblivion of history.

Is there no power of conscience, justice, fairplay and human concern, in this country, that would join the displaced and exiled KP in his struggle for reclaiming and regaining his inborn status and rights as a "person" of the soil of Kashmir? The fulfillment of the dream of this "person" of Kashmir will harm none whatsoever, but it will give him eternal peace and contentment "to breathe this native air, in his own ground."

Death of a Gentleman: A Tribute to J.N. Raina

By Shyam Kaul

Kashmir Sentinel Editorial and Staff mourns the death of Sh. J.N. Raina, Sh. Raina contributed regularly to Kashmir Sentinel right from its inception. As a tribute to this professional journalist of unsullied integrity, we are publishing an article written by Sh. Sham Kaul (eminent journalist) in memory as a tribute to Lt. Sh. J.N. Raina. –Editor

By Shyam Kaul

All his life, manor part of which he spent as a professional journalist of unsullied integrity, J.N. Raina studiously preserved the ethical standards of his vocation. He was never once proved wrong in his life, nor so in his death which came to him on the intervening night of October 22-23, In Pune, where he lived with his family since 1990.

Hours before he passed away, JN had made a telephone call to a journalist colleague in Jammu, Ashok Pehelwan, and had told him in an ailing voice to give his last ‘Namaskar’ to all friends here, and convey to them his ‘final adieu’. He keep his word by departing only a few hours later.

For well over three decades, JN served as the chief of Srinagar bureau of leading national news agency, UNI, before moving over to Mumbai office of the agency in the wake of the eruption of militant violence in Kashmir.

The two of us, pestered by threatening phone calls and other intimidatory ways, were the last non-Muslim journalists to leave Srinagar when our fellow city journalists advised and insisted that we should do so for the sake of our security and safety.

Before that, the Governor, Mr. Jagmohan, had suggested that we should shift to Tourist Reception Centre complex, a safer place, and operate from there. But it was not feasible, simply because we would not be able to do justice to our work, closeted all the time in a room.

During his prolonged posting in Srinagar, his office near Central Telegraph office, was JN’s temple where he spent all his time, wholly dedicated to his work, sometimes late into nights. The outcome of the toil of his pen was there for the readers to see and relish the quality, accuracy, authenticity and excellence of his despatches, day after day.

JN was a man of few words, a soft-spoken person, and normally talked only when talked to. He rarely mingled with his tribe in their occasional gala get-together and merry bases. Interestingly, however JN had a subtle sense of humour and could sometimes entertain others with his quips and cracks, when he opened up. One recalls a professional tour of a group of media persons to Bihar and West Bengal several years ago. As we went around visiting places, it was a revelation to us to see JN enlivening the ambience with his pithy comments and observations. While going round the zoo in Kolkata, we saw a tiger, fully stretched, sleeping peacefully in his cage. Pointing to the animal, JN quipped, “He should have been working for a news agency to know the price he would have to pay for sleeping so deeply and unmindfully during the rush hours of the broad day.”

Despite his comparative aloofness and distance from his fellow journalists, JN was highly respected by everyone in the profession. It was not uncommon for his colleagues to often seek last minutes confirmation from his the credibility of some sensitive new reports and stories, which, at one time in early days of militancy, were a plenty in Jammu and Kashmir. JN would never fail to respond and oblige. In fact we would often say, “Ask Raina Saheb, if the story is factual and if he has done it.”

A gentleman journalist in the manner and nature of veterans like R.K. Kak and Mohammed Sayeed Malik, who are held in high esteem by the fraternity, JN was a fine gentleman too, bearing malice towards none, and never doing any working to anyone. Those who came close to him were struck by his simplicity, decency and humility, and, of course, his dedication to work and his professional calibre.

By virtue of his standing in the professional as chief of bureau of a national news agency, JN did have a latent clout, but being essentially a self effacing person, he never threw about his weight, and never sought or asked for any favours and concessions from the establishment. His primary concern was his work and duty and he did proud to the agency and people he worked for, earning their acclaim and appreciation, as also of the entire media community of this state.

Honesty and humility were quintessentially the cardinal attributes that thoroughly permeated JN’s persona. As a man, a media person, an associate, a friend, a conscientious professional, a social being, and a householder, honesty and humility stood out in all his actions, workings and dealings. And it has been said, “An honest man is the noblest work of God.”

PN Jalali – A Homage to an uncommon man

PN Jalali – A Homage to an uncommon man

By Shyam Kaul

Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah, during his second tenure as head of the Jammu and Kashmir government, inducted a prominent National Conference (NC) leader from Baramulla, Mubarak Shah, into his cabinet. After Shah had got ensconced in his ministerial position, he one day invited media persons to his official residence near Zero bridge in Srinagar for an informal chat with him. During the course of interaction with him, we found Shah to be an engaging talker. He told us many interesting things about the political movement in Kashmir, and his association with Sheikh Abdullah. Shah also told us that he and PN Jalali, who at that time represented PTI in Srinagar, has been active as “underground workers of NC”, headed by Sheikh Abdullah, who had launched Quit Kashmir movement in 1942, against the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir.

Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah, during his second tenure as head of the Jammu and Kashmir government, inducted a prominent National Conference (NC) leader from Baramulla, Mubarak Shah, into his cabinet. After Shah had got ensconced in his ministerial position, he one day invited media persons to his official residence near Zero bridge in Srinagar for an informal chat with him. During the course of interaction with him, we found Shah to be an engaging talker. He told us many interesting things about the political movement in Kashmir, and his association with Sheikh Abdullah. Shah also told us that he and PN Jalali, who at that time represented PTI in Srinagar, has been active as “underground workers of NC”, headed by Sheikh Abdullah, who had launched Quit Kashmir movement in 1942, against the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir.

As Shah was giving these details, I intervened and told him, “Mr. Shah you have long since come up overground while Jalali is fated to perpetually remain underground.”

What I actually meant to tell Shah was that the role, service, and sacrifices of most of those active during the Quit Kashmir movement has been well recognized and rewarded, but PN Jalali was one among others who never found any political accreditation or recognition, let alone any recompense or reward.

Jalali had been drawn into the political movement, set in motion by Sheikh Abdullah, as a student, and stood associated with it as an enthusiastic activist of the youth wing of NC, right up to early 1950s. He suffered the wrath and excesses of the Maharaja’s regime, including imprisonment, as did many other young and educated workers, who included both Kashmiri Pandits and Muslims.

Sheikh Abdullah took a liking for youthful Jalali, who, he found had a deep and captivating singing voice. Jalali would often recall how he, as a student, was asked by the Sheikh to climb up to the stage at the NC public rallies, and sing a revolutionary song or two to enthuse the gathering.

As a youth worker, Jalali would recollect that he was assigned some tasks by the party leadership. One such task was to be with the workers of the government-run woollen mills in Srinagar and impart elementary political education to them, with a view to making them aware of their rights and also educating them on the political developments in the state.

It was during those early formative years of his life that Jalali, under the influence of his senior colleagues, and his own craving for knowledge of intellectual and political movements, made extensive study of communist literature. In fact it was trendy for the educated youth of mid-20th century to read Marxist literature. Jalali, like quite a few other Kashmiri youngmen, found it in perfect consonance with his yet fresh and unprocessed political aspirations. For the rest of his life Jalali remained uncompromisingly wedded and committed to the Marxist ideology. From NC he graduated to the Leftist politics, associating himself with the Communist Party and staying so all his life. He would also speak of his disillusionment with the NC and its leadership, because he felt that the high ideals it had set for itself were jettisoned half way through, and instead it became a race for material benefits rather than the fulfilment of ideals.

His perigrinations, as a student, into the active, and often hectic, politics of the day, cost Jalali fairly heavily in his studies. It took away at least three precious years of his college education. It was only after 1947 that he resumed his studies, did graduation and then proceeded to Lucknow to join MA classes in political science in the university there. But within a few months his ill health prevented him from pursuing his studies. He was hospitalised for surgery, but he left the hospital and after some time proceeded to Czechoslovakia with a youth delegation of the Communist Party and also for treatment of his ailment. It was there that he first met his future wife, Sumitra, a Bengali girl, also associated with the communist movement.

Back in India, Jalali took up journalism as his wholetime profession, though before that also he had been occasionally writing columns for progressive periodicals. He worked for weekly Blitz of Bombay and Partiot of Delhi and also contributed to a news agency. At the commencement of 1960s Jalali joined Press Trust of India (PTI) in Srinagar, when Harpal Nayyar was the chief of the Bureau. As years rolled by, Jalali rose to become the bureau chief of PTI for Jammu and Kashmir, and retired as such. But he still continued to write for some journals and newspapers and stayed a journalist till the last breath of his life.

Having known and having been closely associated with Jalali, as a deeply committed political being and as a mentor and intimate professional colleague, one can say with conviction that Jalali was a dyed in the wool Kashmiri and an unwavering upholder of Kashmiri’s centuries-old civilisational legacy of peace, non-violence, humanism, secularism, harmony and brotherhood of man. Even during nearly two decades of his exile from Kashmir, Jalali kept himself incessantly engaged, working for the preservation and promotion of this noble heritage of Kashmir, all the time striving to contribute whatever he could to bring back normalcy and sanity in Kashmir, in the shape of a life of harmony, brotherhood and togetherness of all the sections of Kashmiri society. He inspired many a young men and women who continue to be dedicated to the realisation of his dream.

The most striking attribute of Jalali’s personality was his inborn humanistic and secular convictions and his professional excellence as a journalist. As a student, I used to attend some of the political study circles, conducted by Jalali as a communist activist, initiate the greenhorns into the ABC of leftist ideology. One still comes across many of them, even in rural areas, who get nostalgic about the past and recall the enlightening experiences of Jalali’s study circles.

Many of my colleagues, who like me joined the profession of journalism, when Pranji was fully established in it, will recollect how we would pore over his news stories, despatches and articles, to find guidance and inspiration. He was simply brilliant, analytical and incisive when writing on political subjects. The articles he wrote were specimens of facile prose, and always educative, informative and thought provoking.

As a bright and energetic youngster with stars in his eyes, Jalali had almost forsaken his education to make his debut on the stage of the most powerful political party of pre-independence era. But the circumstances prvented him from making this stage a stepping stone for a political career. He fought his own way through life, and, as a common man, ended up as a highly respected journalist. Ultimately, though, it is the man in the street who weaves the fabric of a robust, pragmatic and forward-looking society. Jalali was one such man.

Whether it was his role as volunteer of the people’s militia to repulse the invasion of the marauding tribals from Pakistan, before the Indian army’s arrival in Kashmir in 1947, or whether, as a political activist, it was his single-minded commitment for strengthening the secular and humanistic values of Kashmir, or whether as a journalist, it was his contribution in writing as a perpetuator of Kashmir’s noble ethos, and as an upholder of objective journalism, Pranji was always there in the front line.

Soon after Jalali’ death, Jammu-based media persons organised a condolence meeting at the Press Club. Farooq Abdullah, who was one of the speakers, paid a poignant tribute to the departed journalist. He also lamented that the governments in Jammu and Kashmir had not ever done anything by way of recognition of distinguished journalists of the state for their services in building a healthy socio-political system here.

I was tempted to ask Dr Farooq Abdullah what he had done in this direction when he was the chief minister of this state, not once, but thrice. I also wanted to tell him that ingratitude was the hallmark of most politicians in this state. But I did not do so, the solemnity of the occasion did not warrant the raising of such issues.

As a person, Jalali was highly companionable and chatty. Like late Shamim Ahmed Shamim he was uncontainable talker. One recalls that when Shamim would walk into Srinagar coffee house every morning, people at different tables would invite him to join them. He had only one answer. “Only if you are prepared to listen to my “taqreer”, (speech)”. This was true of Pranji also.

It was a treat to listen to Jalali on wide range of subjects, from politics, to history, to communism, to books, to music, down to trade unionism, and, of course, his own reminiscences of the past. He had a pungent sense of humour and like a typical Kashmiri, could enjoy a joke at his own expense too.

As mediapersons we would be touring often, our favourite pack being Jalali, Mohammed Sayeed Malik, Yusuf Qadiri, Maqbool Hussain and myself. On one such tour we went to Kupwara. On our way back in the evening Jalali wanted to buy some fish at Sopore. We went to the river bank but he couldn’t find the fish of his choice. As we were making our back, a buxom fisherwoman called out and offered a large fish to Jalali which he instantly liked and bought.

Then he asked the woman, “ why didn’t you call me while I was looking for fish from this end to that when you had this fine stuff to sell. The fisherwoman replied innocently and unpretentiously, “ I did call you several times, but all you did was to show your posterior to me.”

On our return journey to Srinagar, the peppery retort of the fisherwoman sent us all into guffaws all the way.

A Tribute to Saqi

by Shyam Kaul

Poet, writer, dramatist, scholar, researcher, encyclopaedist, specialist in Kashmir's cultural and literary heritage, authority on the Valley's Rishi tradition - all rolled into one - Moti Lal Saqi.

Poet, writer, dramatist, scholar, researcher, encyclopaedist, specialist in Kashmir's cultural and literary heritage, authority on the Valley's Rishi tradition - all rolled into one - Moti Lal Saqi.

A simple villager, who never shed off his pastoral homeliness, humility and open-heartedness, who never allowed even a grain of false ego enter his head, inspite of recognition, both at state and national levels, and who always lived the lily of an honest and eager learner till his last breath. That was Saqi - ever lively, ever communicative, ever cheerful.

When I think of Saqi the words of the great French philosopher Voltaire, come to my mind. He had said, "not to be occupied, and not to exist, amount to the same thing".

Saqi kept himself perennially occupied with finer pursuits in life. Put your finger anywhere on the literary and cultural canvas of Kashmir, and you will find Saqi's name there, as a contributor, a researcher, an elucidator, a commentator or a scholar. All that kept him occupied were his creative endeavours and his pen seemed to reach everywhere. In these days of pin-pointed specialization, one hardly finds any equal to this man of multifarious brilliance.

When the physical and physiological makeup of his person, especially his heart? prevented him from keeping himself actively occupied, as he had done all his life? Saqi ceased to exist. He died.

Like all displaced Kashmiris, Saqi's soul had been deeply lacerated when circumstances drove him out of Kashmir, the land of his ancestors. Everyone loves his land of birth, but Saqi had done so, sometimes with the passion of a lover, sometimes with the care of a doting mother, and sometimes with the dedication of an ardent admirer. His only possession, only asset and only wealth, was his pen, which he used all his life in praise of Kashmir.

Some years back I once told him that since our displacement, he had gone a little slow with his pen. He responded with a deep sigh and recited a coupled of Nadim:

Mye khoon-e-dil az syatha chhu chyon kyut

Tsu thav pagah kyut sharaab Shaqi

Then, after a pause, he added, with yearning in his eyes, "because our pagah' (tomorrow) will be in Kashmir". He did not live to see the 'pagah' of his dreams. Many of us won't, either.

Reproduced From:

Unmesh - Monthly Newsletter of N.S. Kashmir Research Institute

Sushil Aima

‘HAIL, YE INDOMITABLE HEROES, HAIL !’

By Shyam Kaul (Safapuri)

In mid-eighties, when young Sushil Aima, a 12th class student, sought admission to the National Defence Academy, he did not inform his parents or any other member of the family. He feared that with the exclusive artistic background of the Aima family, nobody would approve of it. But after he was selected in 1985, Sushil reluctantly went to his father and gave him the news, fearing that the answer would be a firm ‘No’. But that did not happen. His father, Makhanlal Aima, an insurance officer, did not get angry, but he did appear visibly surprised.

sought admission to the National Defence Academy, he did not inform his parents or any other member of the family. He feared that with the exclusive artistic background of the Aima family, nobody would approve of it. But after he was selected in 1985, Sushil reluctantly went to his father and gave him the news, fearing that the answer would be a firm ‘No’. But that did not happen. His father, Makhanlal Aima, an insurance officer, did not get angry, but he did appear visibly surprised.

‘Papa’, Sushil told him, “joining the army has been my dream and today my dream has come true. I assure you I will not disappoint you. I will make a good soldier”.

Major Sushil came from a gifted family of Srinagar. His uncle, late Mohanlal Aima, was among the moving spirits of the post-1947 revival of Kashmiri music. He lifted the Kashmiri “chhakri” from its plebeian moorings and gave it popularity and respectability among the high-born Kashmiris. Through the medium of newly established radio station in Srinagar, he was instrumental in bringing out the “sufiana” music from the “diwankhanas” of the elite and taking it to the homes of common people.

Omkar Aima, another uncle of Sushil, was a stage personality before he moved on to Bombay films, starting with the lead role in first-ever Kashmiri feature film, ‘Mainzraat’.

Satish Kaul, a cousin of Sushil, carved a place for himself, both in Hindi and Punjabi films. Another cousin, Alok Aima, has made a name in Hindi and English theatre in Dubai.

Sushil was commissioned in the army in 1988, as the years rolled by, he grew into a fine soldier, and, when the moment of ultimate challenge came, he touched the pinnacle of valour, which any soldier anywhere in the world would be proud of. In his brief career he earned the praise of his superiors for his bravery, initiative and leadership qualities, especially, during his stint in Doda district in Jammu and Kashmir, one of the worst militancy-affected areas.

In 1997, Sushil was given the rank of a Major. In 1999, when he was 32, with a promising future ahead of him, he was martyred in Poonch sector of Jammu and Kashmir, defending his motherland. He fought valiantly till his last breath against the Pakistani intruders, and joined the select ranks of the martyrs of the great Indian army. In his death, in the prime of his youth, Major Aima covered himself with glory, and brought honour to his family, his people and his country. For a country, no glory can be greater and nobler than that brought by its soldier sons who lay down their lives while defending the honour of their motherland. Sushil Aima immortalised himself as one such soldier son of India.

The first day of August ’99 was hot and humid. Makhanlal Aima and his family were home at Palam Vihar (Haryana), trying to ward off the oppression of the sultry weather. But they were also eagerly awaiting the arrival of Sushil, who was to join the family to celebrate his fifth wedding anniversary, the next day, August 2.

But Major Sushil did not arrive. He never did. Instead came a stupefying shock, a message from the army, that he was no more. He had been killed in an encounter with Pakistan-backed mercenary terrorists in Poonch, where he was posted, on the eve of his wedding anniversary.

Late at night, when Major Sushil was resting after having made preparations for his departure for Delhi next morning, news was brought to him that a large group of foreign mercenaries had assembled on a nearby hill. It was learnt that the group had plans to attack a village in the vicinity, largely inhabited by members of one particular community.

A hurried conference was held. It was decided to go into action, surround the terrorists, and then launch a full-blooded attack, to be led by Maj Sushil. The young officer and his jawans soon made contact with the enemy and a fierce encounter followed. It lasted for seven hours, and ended up with a hand-to-hand fight, with heavy losses among the intruders. Two terrorists fell to the bullets of Major Shushil, but in the later stage of the encounter, he was fatally wounded when a bullet hit him in his left temple. Holding the revolver in his left hand, he also shot dead the third terrorist who had fired the fatal shot at him. Then he provided cover to a colleague, who had been grievously injured in a grenade blast, and helped him crawl to safety. It was then that Major Sushil’s end came.

When the body of the deceased hero was brought to his home at Palam Vihar, hundreds of people had gathered there to be with the bereaved family in its hour of grief. They stood there, men and women, in silent sorrow. Not many had seen or known the young army officer, but here was India, paying its homage, to a martyred son of India.

Makhanlal Aima, holding in his arms his nine-month old grandson, Sidharth, was a picture of restraint and dignity. His friends, crowded round him with words of sympathy and consolation. In a choked voice he told them, “it is an irreparable loss to all of us, and a perpetual agony for the two small kids and their young mother. But I also think of scores of other parents and relatives, who, like us, have been receiving the dead bodies of their soldier sons from the battlefront. I don’t consider it as mere death. It is martyrdom. A moment of pride and honour for all of us.”

Later when Major Sushil’s body was taken for its last rites, Palam Vihar was transofmred into a sea of people. Thousands of them lined the road, among them school children too, whose schools had been closed for the day. Businessmen closed their establishments and shops to join the funeral procession. From ministers of Haryana, led by Revenue Minister, Kailash Sharma, to the local sarpanch, Ranjit Singh, there was hardly a civil or army dignitary, who was not there to bid farewell to Major Sushil Aima. His officers and colleagues in the army were there in full strength.

It was a spontaneous gush of sorrow. It overwhelmed the Aima family. Omkar Aima could contain himself no more. With tears trickling down his cheeks he thought of the dark days, a decade ago, when the eruption of terrorism in Kashmir, had driven out the entire Pandit community from the Valley. At that time no fleeing Pandit knew where he would find safe refuge. Everyone of them wondered whether he would be owned anywhere and whether he would belong anywhere.

Walking alongside the cortege of his nephew, Omkar felt Major Aima was the son of India and the exiled Pandit community belonged to the whole of India, and every nook and corner of the country was its home.

Held by his grandfather in his arms, little Sidharth was made to light the pyre of his father, who had been described as the “bravest of brave” by a senior officer of his, Maj Gen A Mukherji. Who knows what dreams Major Aima had dreamed for his little son and four-year daughter, Ridhi. But one can be sure that he died with the confidence that a grateful nation, he left behind, would give them a happy childhood and a secure future.

A few days later a special function was held at Rohtak where Haryana Chief Minister, OP Chautala, handed over a cheque of Rs 10 lakhs to Archana Aima, widow of Maj Sushil. The hearts of Omkar and Makhanlal Aima, who were present, brimmed with gratitude for the people of Haryana, Maj Sushil’s adopted state. But a gnawing feeling rankled deep down in their hearts. Sushil was born and brought up in Kashmir, and he was martyred on the soil of Kashmir. And yet, the chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir, Farooq Abdullah, did not have a word of sympathy or condolence to convey to the bereaved Aima family.

Sushil has gone to eternal sleep, as did many brave soldier sons of this country during the summer of 1999, after shedding the last drop of their blood for the honour and integrity of their motherland.

On Fame’s eternal camping ground

Their silent tents are spread,

And Glory guards, with solemn ground,

The bivouac of the dead